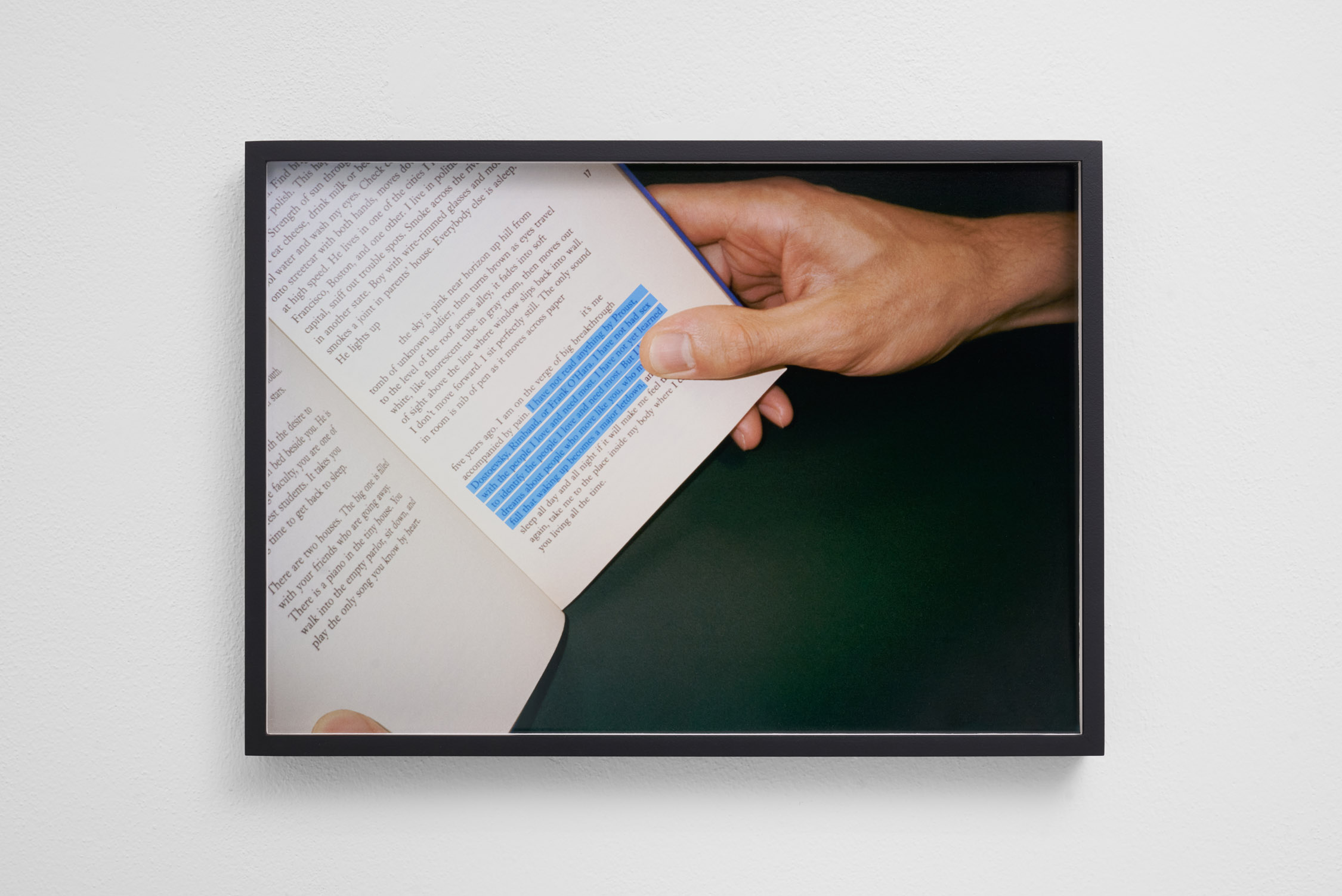

Karl Ove Knausgård has a fondness for the baroque. In the second volume of the magnus opus that is his autobiography, the Norwegian writer, an epigone of Proust, notes: “…and when the mobility that art cultivated became immobile, this was what should be avoided and to which one should turn his back” (1). If mobility is an essential condition for art not to fossilize, then the idea of a hypothetical structure understood as a constraint could announce its dissolution. And what if it were the prerequisite for a rebirth instead?

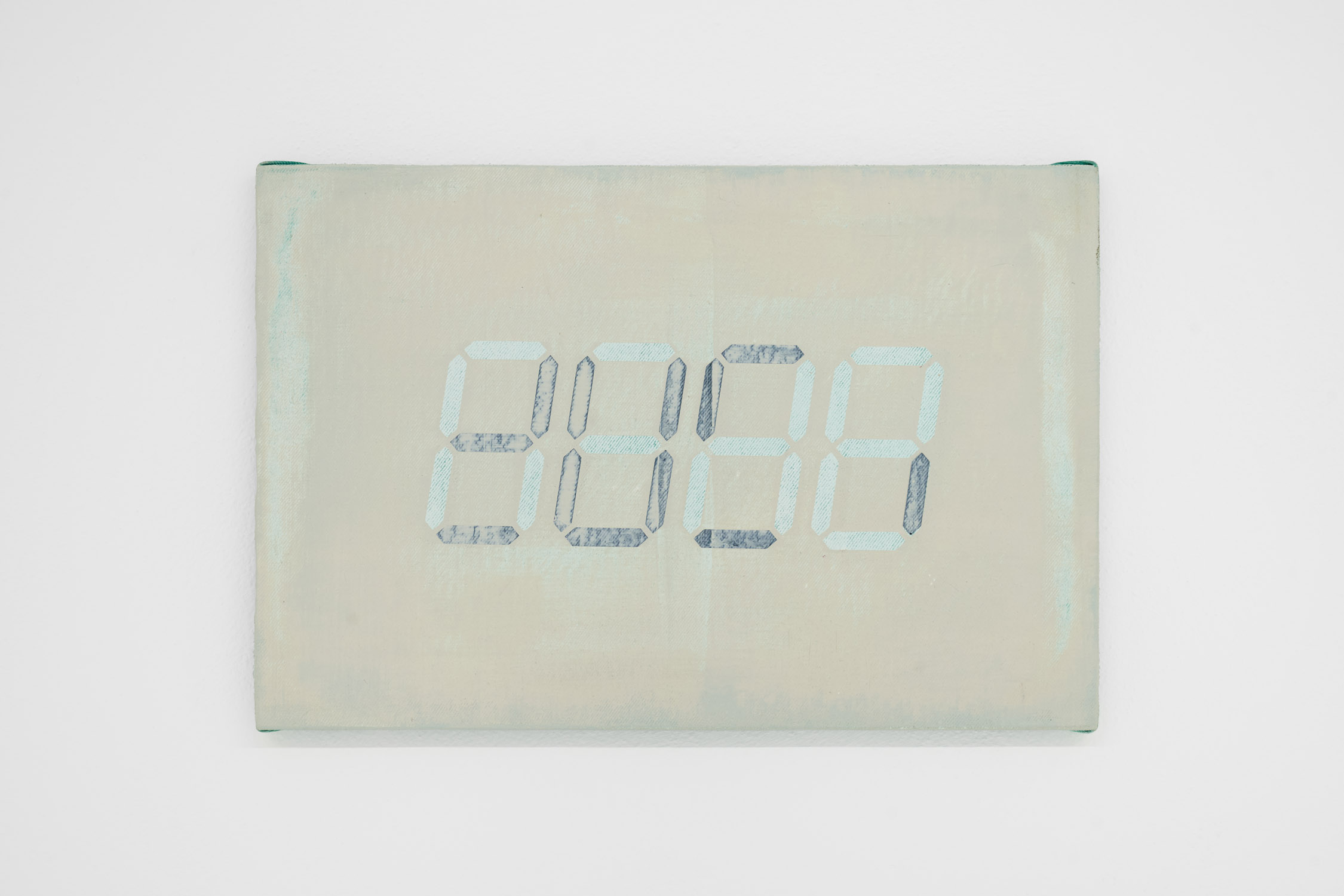

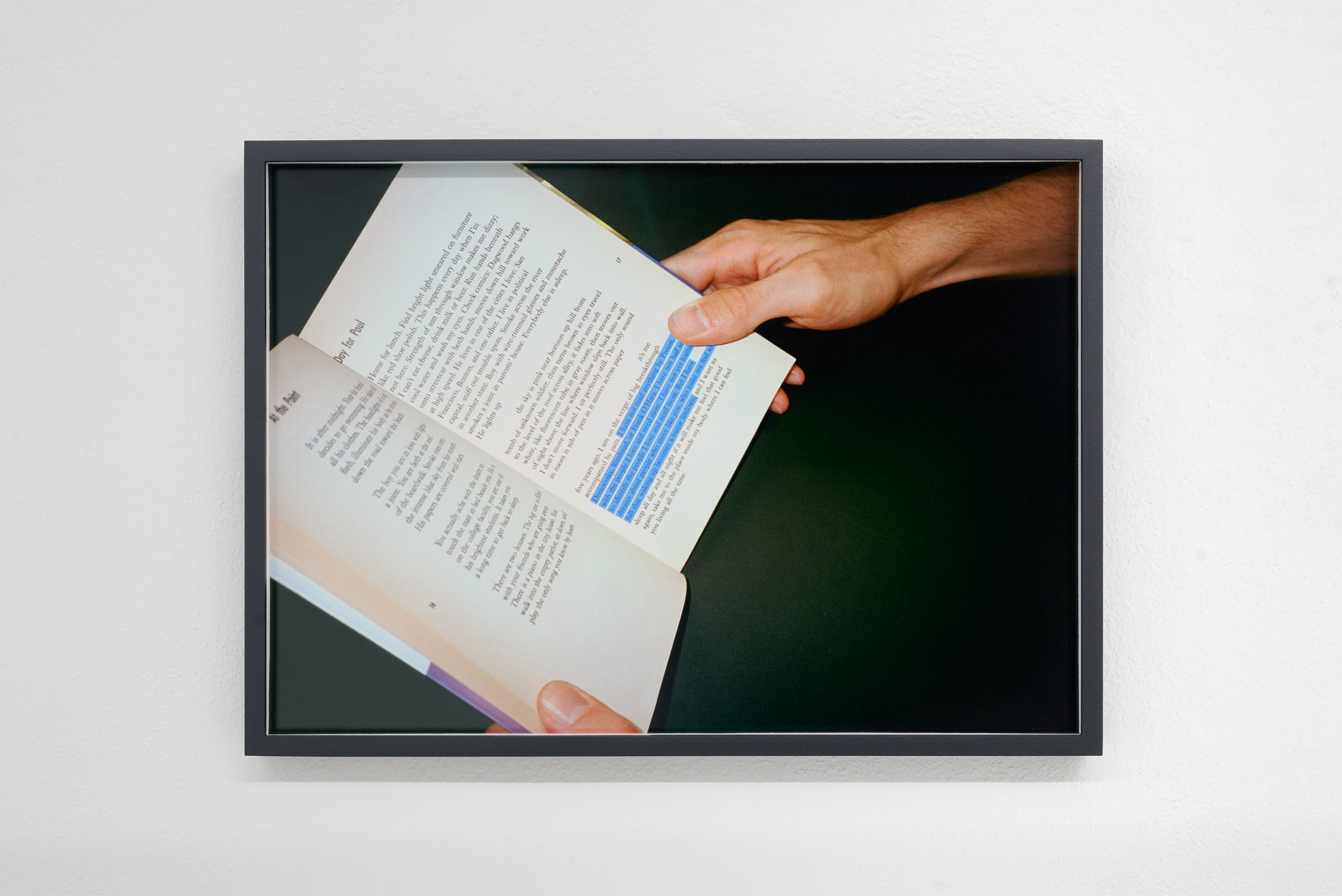

In the exhibition “Hidden Structures”, Triangolo gathers the perspective of a group of artists who, knowingly or not, and through various mediums, engage in reflections on such theme. What are the structural limits of a work of art? To what extent is the artist aware of their existence?

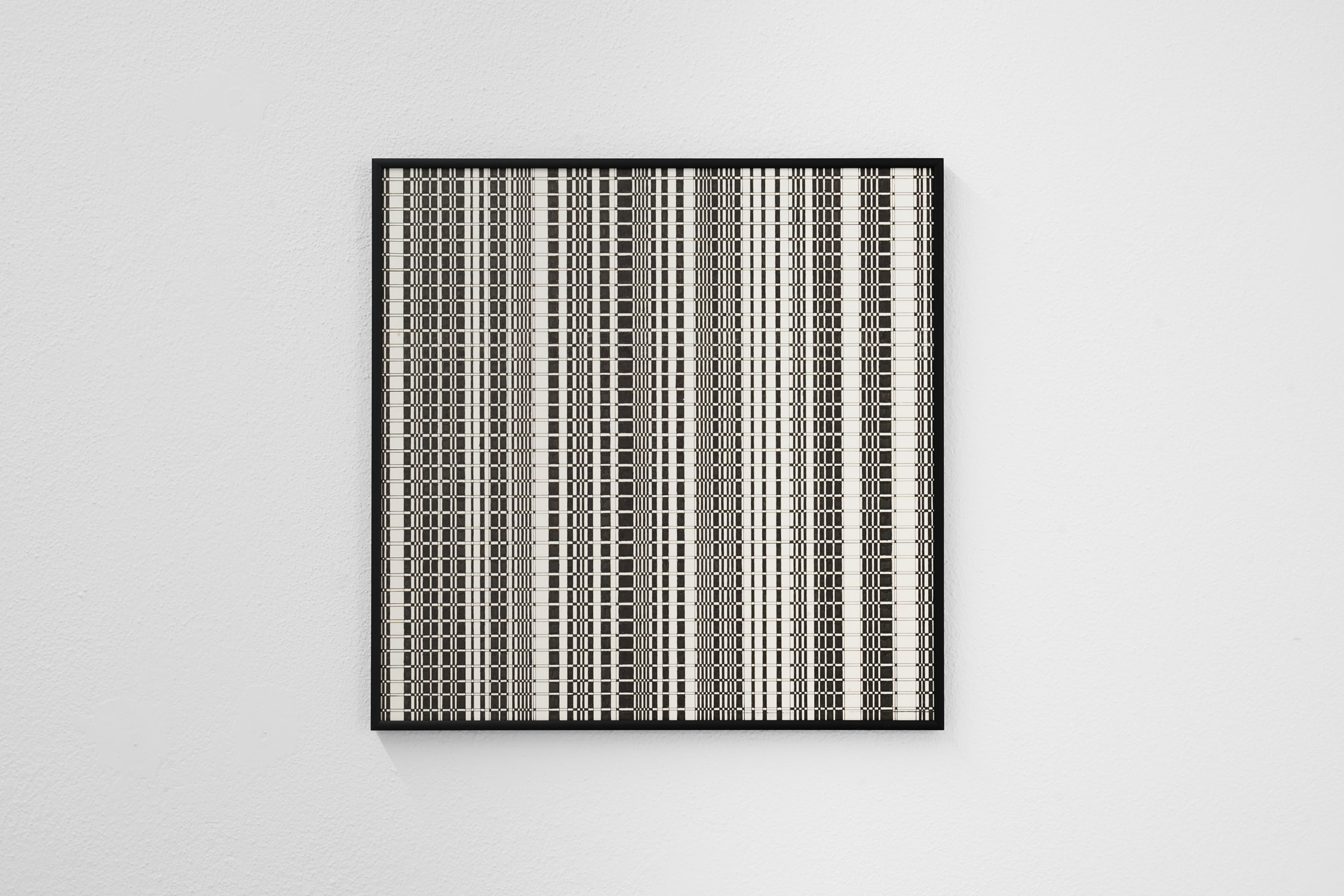

We have been taught the precept that, precisely where the composition of a painting seems dictated by free will, in reality, pyramids and circles support the framework, bestowing harmony. A technical but not immediately visible trick, yet still a cage that would constrain the painter to move within poorly tolerated barriers. If then, from the serenity of the Renaissance we delve into the neuroses of the Baroque, where, quoting Descartes, the judgments of men are based “on some passions that have previously conquered or seduced their will (2), the lesson to be learned is that the upside-down world of the 17th century gives birth to dynamic compositions, where everything moves, rises, falls, and crowds together (3). The man of the 1600s is captivated by the new to the point of numbness and every direction explodes. But this is art at the service of a non-transcendent structure, the ideological one, because the sociopolitical order is untouched (4).

There are, therefore, structures that the artist, as an individual tied to a specific era, has at their disposal and which at the same time, indicate the boundaries of creative decision-making. By observing the exhibited works, the attitude towards them seems to suggest a constant tension between instances of escapism and acceptance, even instrumental. Declared or not, invisible or manifest, whether geometric, mental, or ideological, structures have always existed. The organization of space, body, and time, in every historical phase, is nothing other than the symbolic representation of the disposition and function of all the creative forces present within the fabric of that specific culture

It is the artists who, tied to a determined moment in which they grow and develop, progressively modify and surpass the order from which they spring, thus preparing the ground for the next generation. From this bond to the fundamental symbolic forms of their time, even genius cannot free itself more than what, in its own work, it is capable of contravening already established constants.

Thus, the “mobility” exalted by Knausgård configures itself as the ability to inject vital lymph into what appears stagnant and out of tune with the present, creating new limits, and therefore structures, that replace those that are now inadequate and stagnant, pushing the fence a little further away. “Every limit is a beginning as well as an ending” (5) George Eliot wrote, today as centuries ago.

Let the example of the painter and sculptor of the 15th century exhibited here serve, who, in the figures of the possessed and the thieves, outsiders like that of the artist himself, seem to don the role of those who have dared to challenge the rigid theological framework and its insurmountable margins, ridiculing, for a moment and at great cost, a sclerotic world.

(Carlo Prada)

[1] Karl Ove Knausgård, My Struggle, Volume Two, 2009, p. 432, ed. Nar-ratori Feltrinelli

[2] Descartes, Treatise on the Passions of the Soul, 1649, p. 48

[3] A. Maravall, Culture of the Baroque, 1975, p. 300, ed. Il Mulino

[4] See note 3, p. 376

[5] Eliot, Middlemarch, 1871, p. 1009, ed. Garzanti (2021)