Artist: Henry Chapman

Exhibition title: Prudent triangle

Curated by: Domenico de Chirico

Venue: Labs Contemporary Art, Bologna, Italy

Date: February 20 – April 17, 2021

Photography: all images copyright and courtesy of the artist and Labs Contemporary Art, Bologna

“Prudent Triangle” is the title of a poem by the Serbian author Vasko Popa. The first three stanzas remind me of what I set out to paint:

Once upon a time there was a triangle

It had three sides

The fourth it kept hidden

In its burning center

By day it climbed its three peaks

And admired its center

At night it rested

In one of its three angles

Each dawn it watched its three sides

Turn into fiery wheels

And vanish in the blue of never return

There is a surprising depth of feeling for a two-dimensional shape. The humble triangle is full of longing. Popa’s language — both utterly clear and mysterious — reaches myth by way of the colloquial, as Agnes Martin does.

When I first read this poem, I thought of those Constructivist figures composed of simple geometric shapes made a hundred years ago. That influence once set me on a path seeking exuberance where figuration and abstraction meet. There I found the central form of this work, which suggests a color wheel or a clock. In some, it’s like a figure with outstretched arms; in others, a floral or stellar shape.

The paintings in this exhibition were made in the middle- and latter-part of last year, in response to life as it had changed. It was impossible to ignore grief, which — although it had always been there — assumed an omnipresence I had not known before. In response to grief I have always moved inward, and such movement can be ultimately expansive or restrictive. Here I returned to color, sensing its ‘burning center.’

I have come to think of color as the syntax of painting: its relationships regulate and order the canvas. And, like syntax, color creates a sensory perception of time. To practice color is to be in relationship with the past: through color I am intimately connected to the thinking and feeling of other practitioners, alive and dead, more so than in any other aspect of artmaking. In Popa’s poetry I found a reckoning with time that felt compatible with my own. One of his translators, the poet Charles Simic, calls this a question of authenticity in language. “What words would we trust today is the pressing question? What words would our ancestors use?” What colors would we trust today? What colors would our ancestors use?

As I painted in a country deluded by white supremacy, I thought of my ancestors—among them Jews in the Soviet Union, some who left when it was still possible and others who stayed. I know very little about them, having been shaped by the always-forgetting of white American identity. The histories of colonial violence built into such an identity are not past, but constant—while writing this, white real-estate agents are flying in private jets to storm the U.S. capitol in scenes of grievance that recall the white backlash to Reconstruction.

Popa, who was interned in a concentration camp for several months, later feared the Serbian “nationalist crazies and opportunists.” Simic says: “He could see that, with his Romanian background, he was already suspect in the eyes of super-patriots.” Just such crazies are here now, loudly transfixed by myths of white supremacy and nationalism.

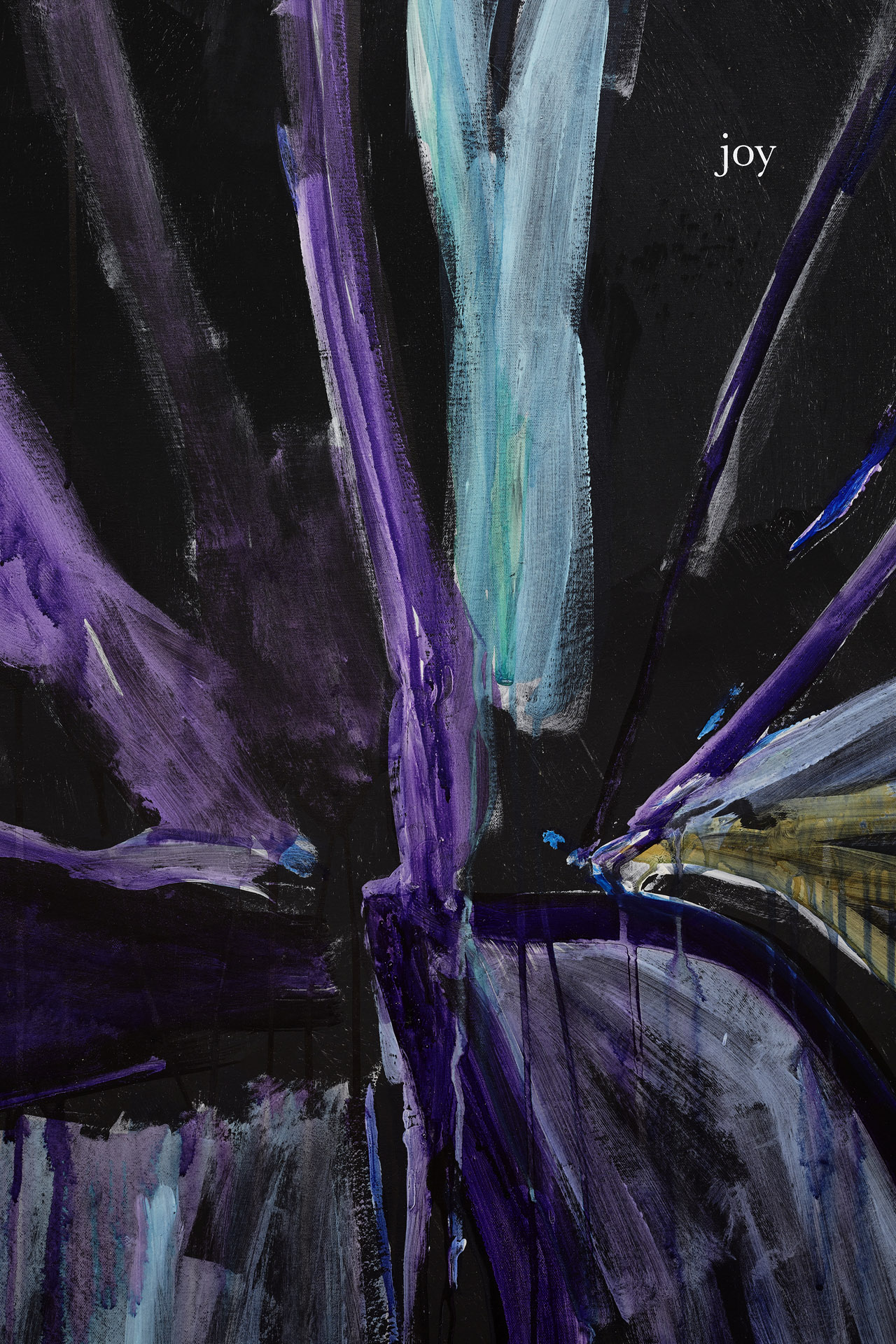

These paintings depart from my previous bodies of work by being painted on a dark ground. During the summer, I had the thought to set my paintings at night; night seemed like the only appropriate time to consider the American shadows and American monsters of the last four years.

The prudent triangle is diligent in its focus on survival — in this sense it reminds me of the pink triangle reclaimed from the Nazi symbol by ACT-UP for the AIDS pandemic and the insistent, morally clear equation, silence = death. In Popa’s poem the triangle’s survival is in the daily reconstitution of its form:

It took its fourth side

Embraced it and broke it three times

To hide it again in its old place

And again it had only three sides

And again it climbed each day

To its three peaks

And admired its center

While at night it rested

In one of its angles

After reading Popa, I think of the forms in my paintings as moving forward and returning at once. They search for a language (what words would we trust today?) made of color, shape, screen-printed words, and mark-making.

I have always wanted painting — the thinking, feeling body of a painting — to speak. Reading one of Popa’s only notes on poetry suggests how: “You speak to the wall. You speak into the dark. You speak into the fire. You speak to the monsters in your dreams. You speak to your own death. You speak to her death, speak to death. You speak to water…”

Henry Chapman, born 1987, is an artist living in Brooklyn, NY. His solo exhibition, Prudent Triangle, runs until March 20.

***

Domenico de Chirico (DDC): How do you approach painting?

Henry Chapman (HC): I’m the son of a pianist and some of my terms for understanding painting come from music: practice, performance, movement, time. These terms reflect how I make each painting — in one or two sittings, at a scale requiring my full body, and based on studies made in watercolor first. They also reflect my way of asking these questions of painting: what is the right language to embody experience? What is language? What is body?

DDC: Can you talk about the recurring forms and the repetition of language in your work?

HC: A central form in my work evokes both a color wheel and a clock; in some paintings, a figure reaching outward. In others, a stellar or floral shape. Screen-printed words move around or within these marks and washes of color, often at points where you would find numerals on a clockface. The idea is movement. To move through different modes and concepts — thinking, feeling, speaking, acting. The words themselves are not the painting’s ‘language,’ but part of the language. A part of color.

DDC: How do you think about color in this body of work?

HC: Color in its infinitude doesn’t recognize mastery. Color is a language impossible to fully learn; I think this is why I kept returning to it over months and years of grief. (It too is a language). My newest group of paintings breaks from previous iterations by starting on a dark ground; this is the foundation for questions about time, movement, performance, and practice. The color relationships are limited to shades of black, brown, blue, purple, violet, and green.

DDC: Can you talk about your influences?

HC: My way of thinking about painting was formed by the example of artists who moved easily between mediums, ideas, and categories of mark-making (abstract and figurative, for instance). In no particular order, and to only name a few, artists such as Sigmar Polke; Kerry James Marshall; the paintings and poetry of Etel Adnan; Adrian Piper; Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s Dictee; Rochelle Feinstein; Richard Aldridge.

DDC: What have you taken from looking at these artists?

What I’ve learned from these artists and others is a restlessness about the inadequacy of language

— whether that language is color or English or otherwise.