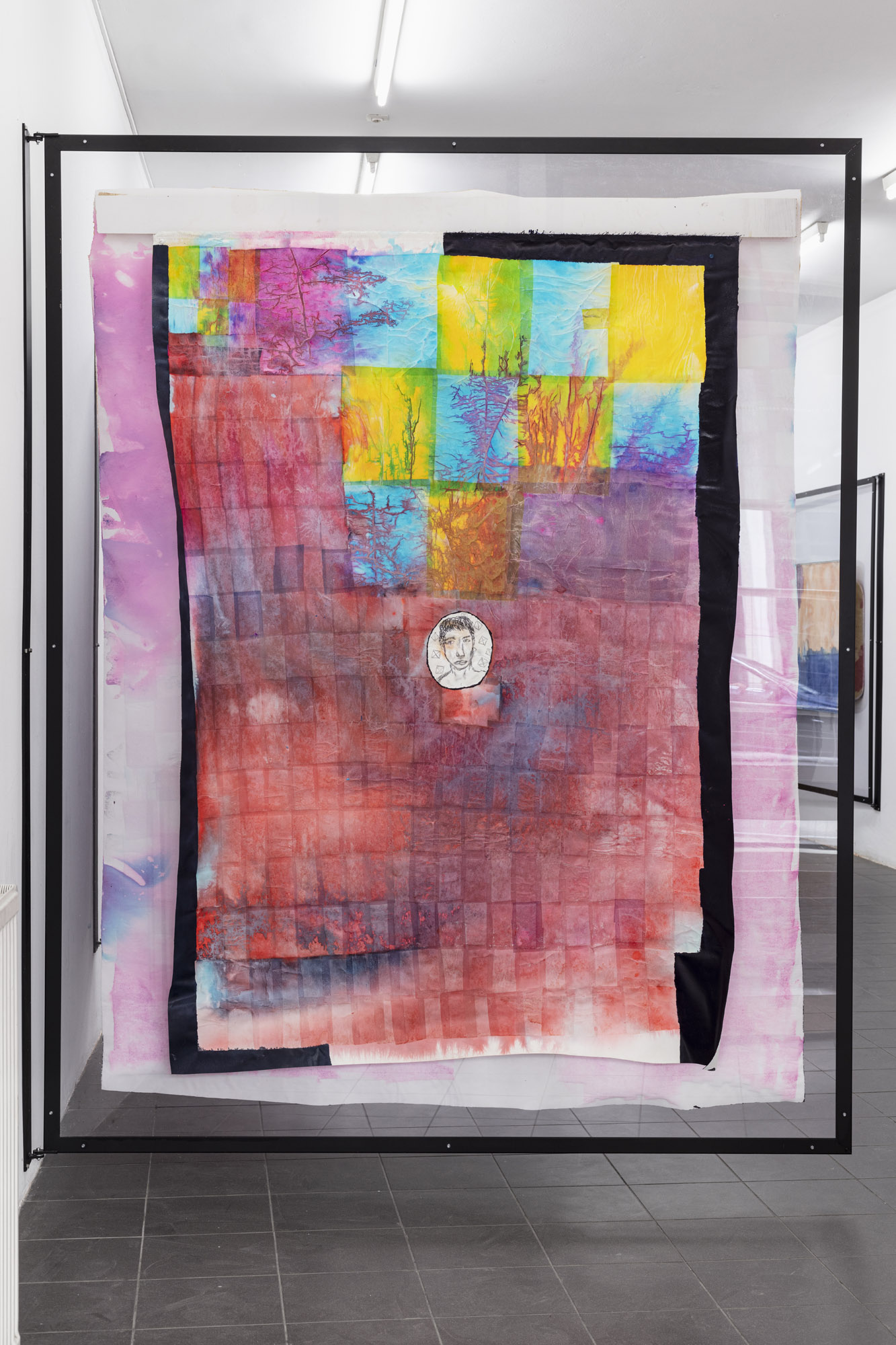

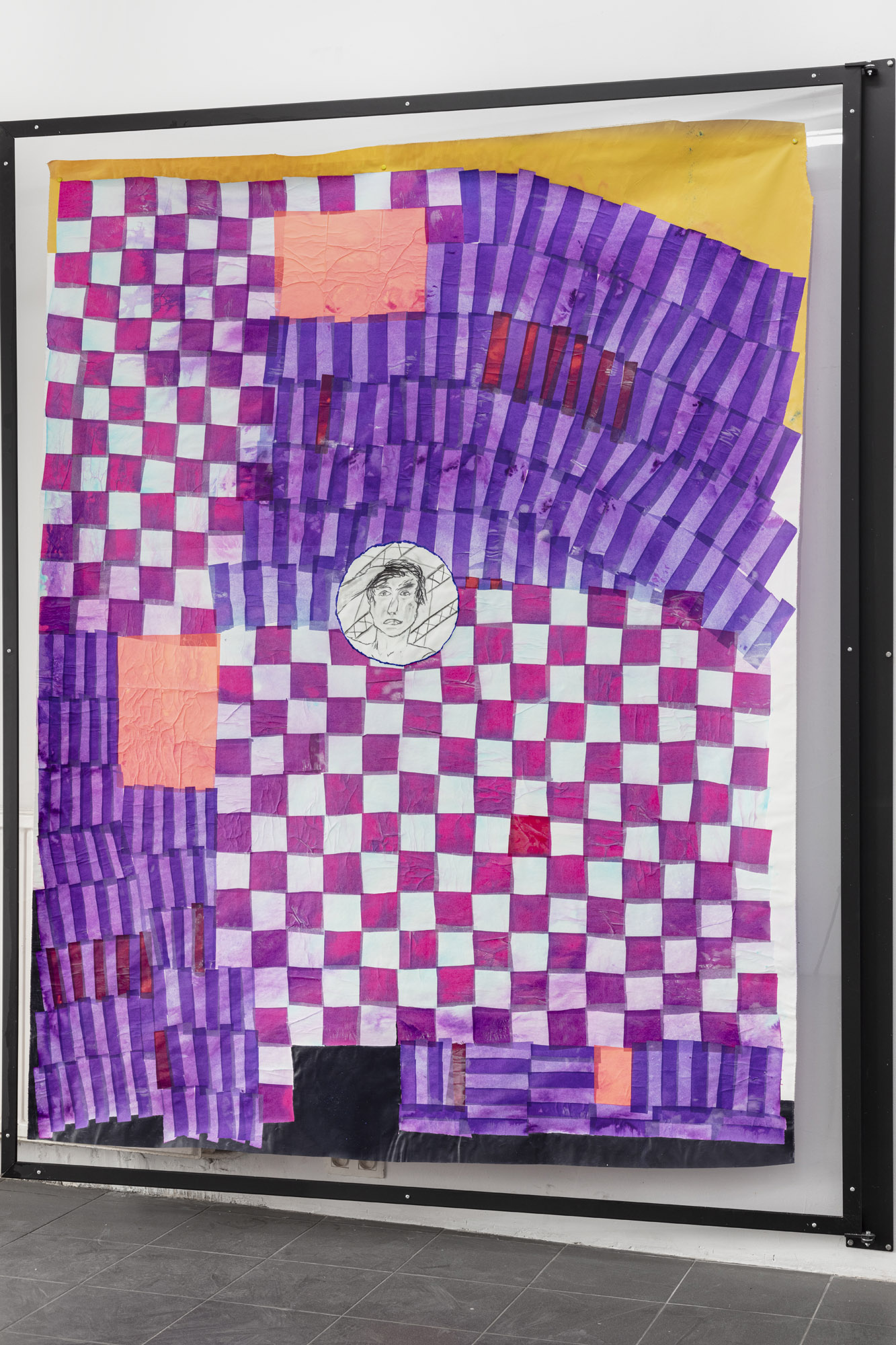

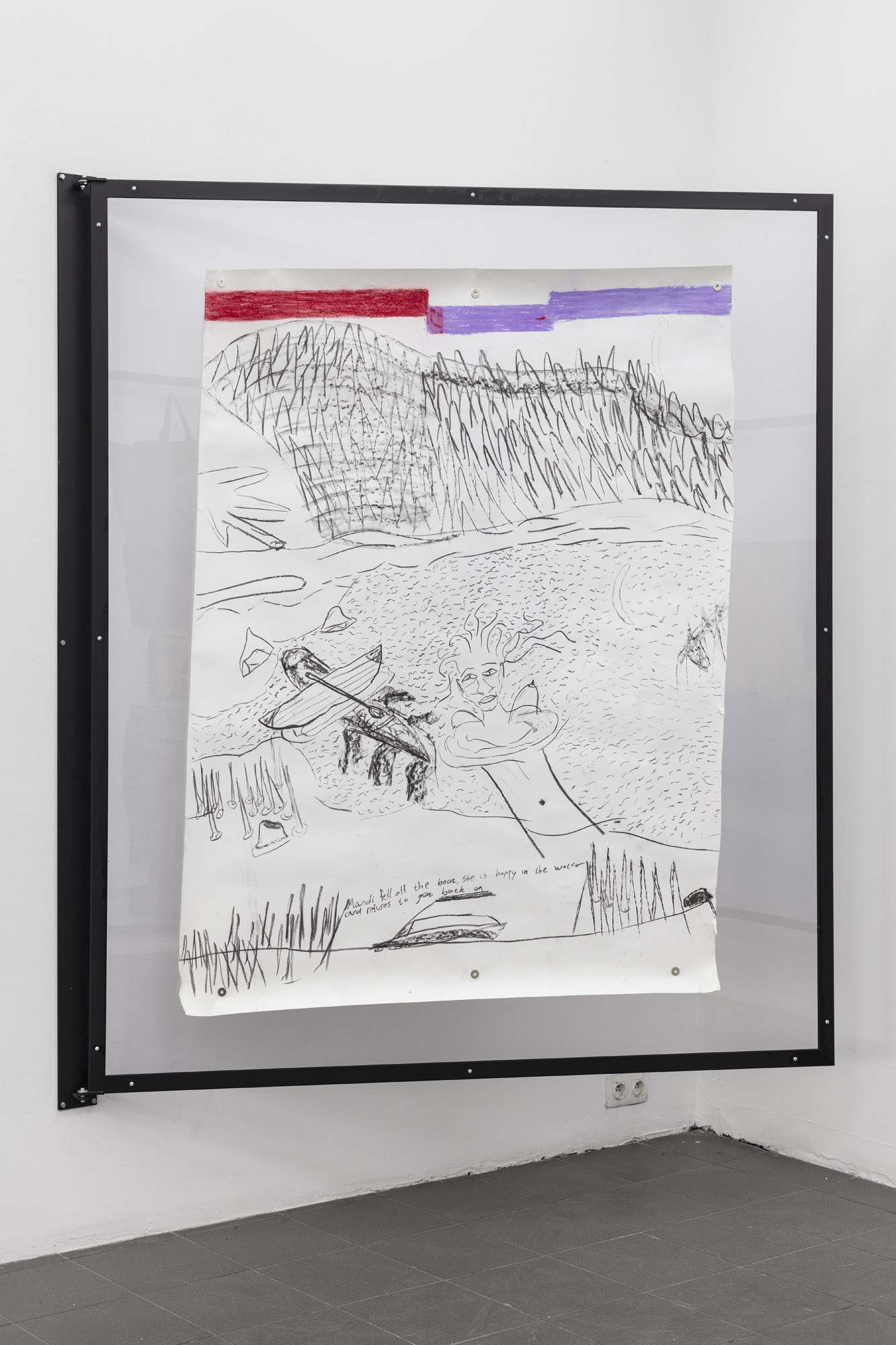

Artist: Henrik Olai Kaarstein

Exhibition title: Necessities

Venue: Etablissement d’en face, Brussels, Belgium

Date: May 28 – July 24, 2022

Photography: ©Fabrice Schneider / all images courtesy of the artist and Etablissement d’en face

What role does necessity play between love and its subject? Is it the person that commands us, or the emotion itself? In Romeo & Juliet, we meet Romeo at the tail-end of his romance with Rosaline, which he describes as a sea nourished with loving tears and a madness most discreet. Doubt follows as a shadow over the rest of the narrative as to whether his subsequent infatuation with Juliet would have amounted to a simi- larly fleeting bout of madness were it not for its unfortunate and irredeemable out- come: death. Shakespeare’s story is more than an ode to love; it is a portrait, like Kaarstein’s, of a fickle and treacherous kind of beauty. In a sad little book from 1898 titled Victoria, the Norwegian writer Knut Hamsun declares that “Love is God’s first word, the first thought that sailed through his mind”:

When he said: Let there be light! There was love… Love became the beginning of the world and its ruler; but it moves in ways filled with flowers and blood, flowers and blood.

The horizon line that divides the world, then, is that between love and light—whether God’s great mistake or his punishment, it doesn’t matter. And as the sea takes on the colour of the sky—or is it the other way around?—we are doomed not to be able to tell the two apart. Rainer Maria Rilke describes the biblical tale of the prodigal son as the story of a man who was loved too much: “it’s only on him that the light falls, and with the light all the shame of possessing a face.” Love rules the world because, like a judge, love makes you the subject of scrutiny by dragging you into the light. It puts you on a piedestal from which you can fall. In Victoria, the good and pure young man Johannes is the prodigal son. He flees the love-light of his home, only to return and shine it on the story’s namesake. But love, as he puts it, is “an anemone that closes up at a breath, and dies by a touch”—perhaps the reason why Kaarstein uses plastic flowers in his work. Like Romeo shone his light on Rosaline one week and Juliet the next, Victoria is not the subject of the story but the more or less arbitrary shape of its name—its victim.

Because love is so fragile, it needs the structure of a name to host it, almost in the way that a virus needs a warm body. It is therefore all the more remarkable that we find in a body of work so romantically inclined as Kaarstein’s such a stubborn lack of naming. There is something anorexic about this lack, and something bulimic about the abundance that takes its place. In love without light there can be no loss because we can’t see its subject.

– Excerpt from the essay ”Flowers and Blood” by Kristian Vistrup Madsen, published in artist’s book Bulimia