Artist: Hendrik Hegray

Exhibition title: Tout Smoke

Venue: Les Bains-Douches, Alençon, France

Date: March 17 – April 23, 2023

Photography: Romain Darnaud / all images copyright and courtesy of the artist, Les Bains-Douches, Alençon and Galerie Valeria Cetraro, Paris

There’s a YouTube video that I like a lot, with just two shots. The first is an overhead shot of an upright empty red bucket with two pieces of wood, left and right, covered in green mesh, leading to the top. We see a guy from behind enter the frame, stretch clear plastic over the bucket, slice the plastic sheet’s center with two crossed cuts of a utility knife, then toss seeds towards the hole with deliberate inaccuracy, the idea being they fall all around the hole – on the plastic, the two small planks, the ground around the pail. Little by little mice show up, drawn by the seeds on the floor, then those on the pieces of wood and the clear plastic, until they fall through the hole in the plastic and collectively jump in one after another, drawn by the seeds at the bottom of the bucket. Gradually dozens of mice are stuck in the bucket. They can’t go back up since the bucket is too high and too smooth. The guy, still seen from behind, then completely opens the plastic. A new shot, this time closer up on the inside of the pail, shows us that the mice have all arranged themselves vertically, their little snouts stretched upwards as much as possible to catch a breath – at the risk of getting wedged in together really tight. End of video.

The final image is frightening, because you think that the mice stuck at the very bottom must not have managed to get their snouts up and into the air; and funny, because there’s this purely collective stupidity in those dozens of little animals looking up at the camera, all upright and frozen to the spot. That mix of fear and laughter, animal suffocation and collective imbecility, lies at the heart of Hendrik Hegray’s drawings. But let’s come back to the trap. It is quite simple, no mechanism, poison, technology – a kind of lazy trap, a pure DIY trap. It takes ten minutes to build the thing and ten minutes to watch the video (whose relaxing music underscores the serenity). Basically, the time Hegray needs to do a drawing. But behind the lazy simplicity of the trap lurks a very surprising lucidity. Let me explain. When you have mice in your place, you never know how many. What is the number x of mice that are lurking at a person’s place? Impossible to answer precisely. So, how do you determine the height of the bucket you need to choose? If x exceeds a certain limit, the mice, by bunching up, are going to naturally return to the surface of the pail’s top and therefore are going to be able to escape. To be precise, those mice that happen to be at the top of the bucket, that is the last ones to fall in, will only have to pop back up once again through the plastic sheet in the opposite direction, descend one of the planks and return to living their murine lives, leaving the others stuck in the bottom. So, I repeat, I don’t see how you evaluate x beforehand. Hence the surprising lucidity of the trapper when he chose his bucket with its particular height, lucidity which I hadn’t thought about the first time I watched. His practical laziness concealed a gift for calculation.

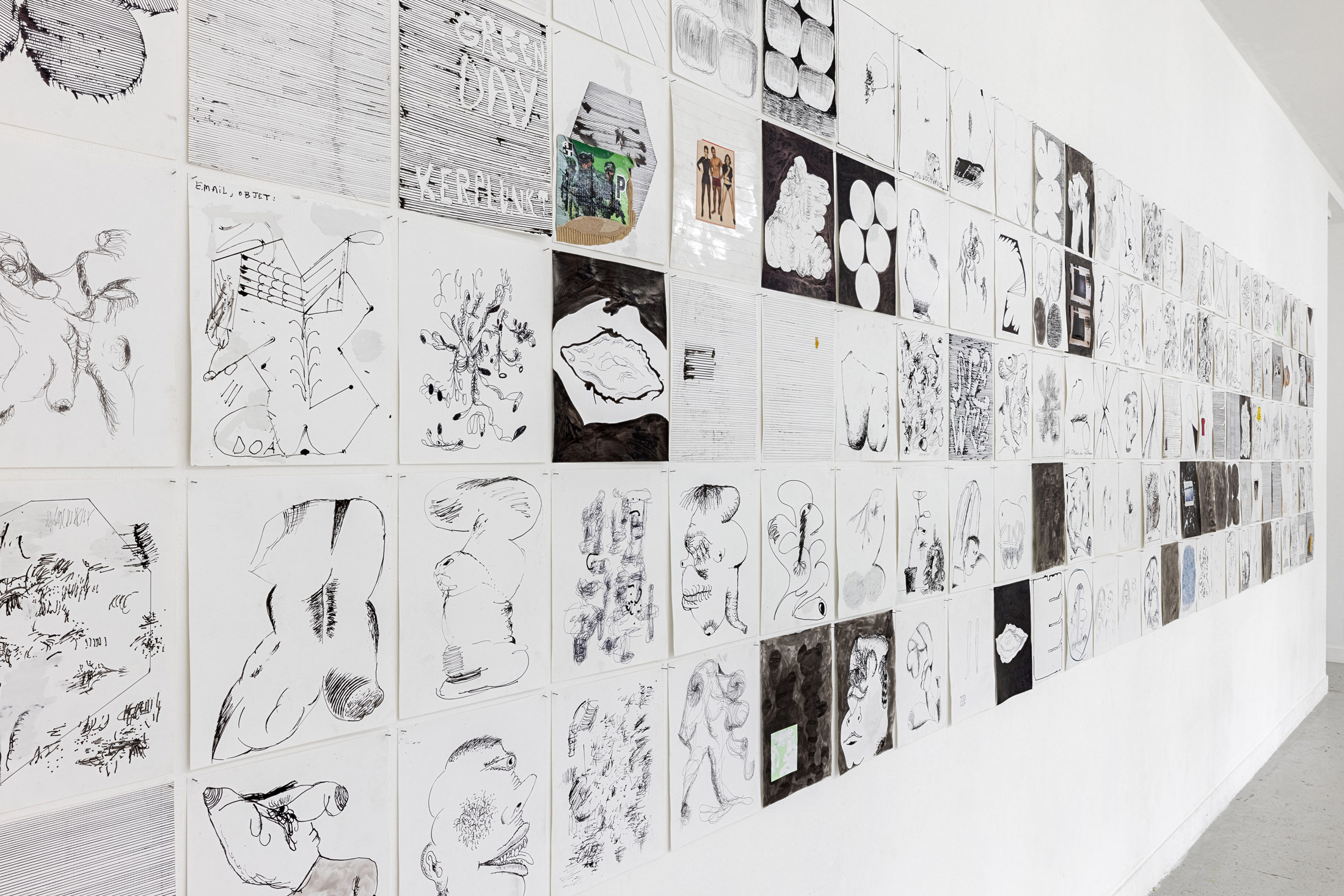

The last fallen are the last arrived. You see them in the video, it’s the slow mice, the ones that hesitate, balk a bit. So the trap’s effectiveness depends on the number of slow mice that are hidden in an apartment. I insist, the slowest, if they are numerous enough, will be the sole ones to be saved – there is doubtless a connection with Hegray’s drawings, i.e., since x is impossible to determine ahead of time, random justice for the weakest! But is being slow a weakness? For an answer, we need to look at Hegray’s drawings more closely. What exactly are his drawings? What do we see there? What are these small paunchy creatures that are carried over from one page to the next, again and again? An obvious hypothesis comes to mind. Hegray draws black deformed sexualized mice, which multiply as soon as he puts his Bic to the sheet of paper. He endlessly draws them, favoring the belly over the tiny snout and wee little feet, a belly that swells and grows hollow with bulges and feces. Sometimes, instead of mice, there are just grids drawn with a ruler, or empty cages. But what does he trap with his drawings? Answer: the viewers at his show in Normandy, who are going to find themselves upright, heads raised before hundreds of tiny mice displayed on the walls (328, to be exact). The more the viewers are numerous, the more they will be packed in – should the show turn out to be a maximum success, a camera filming the bucket-museum in Alençon from above, with a gaping roof covered in a sheet of plastic, will yield the last image of the lazy trapper’s video, but with humans in place of animals. Would one laugh before such an image? Not sure.

So let’s start all over from scratch. It’s the story of a kid from the backcountry called “HH.” He grows up, discovers pop music, girls, movies, boys, posters, and VHS cassettes. The problem is, he lives in a basement and his basement is full of mice. So he can’t invite girls or boys over, but he can collect posters, records and VHS cassettes, then watch mice stuff themselves silly with his posters, records and VHS cassettes. One day, he decides to go up to Paris. But he isn’t earning enough money so he finds himself in the poor outskirts, in a basement in Aubervilliers. There are mice in his basement in the outskirts of Paris. His father regularly buys him sumptuous art books, which HH puts in marbled buckets – to protect them from the mice. One summer, HH meets a girl, from a far-off country, and the mice do not bother her for they are sacred in her country, being tokens of fertility there. The problem is the girl finds HH a bit idle and a social butterfly, because he’s too attached to his little rodents gnawing away at little collections – unlike him, looking at mice gobbling up posters, records and VHS cassettes bore her big time. So she uses a bit of blackmail on him, Either you become an artist, or I leave you. From that summer day on, HH has been doing drawings without knowing how to draw, music without knowing how to play an instrument, and films without knowing how to shoot films. He is forced to do this every day because his girlfriend blackmails him every day. Soon HH has an immense body of work – no French artist is more prolific than him. He finds himself invited to the Palais de Tokyo contemporary art venue. A curator comes to talk to him about the teeming formless as a bulwark against solitary form, sickly infra-realism as a bulwark against patrimonial surrealism, autodidactic urgency as a bulwark against the aristocracy of talent, trashy fanzineship as a bulwark against the deluxe installation, the waste of consumer society (VHS porn tapes, Ivy League biz school foam party flyers, etc.) as a bulwark against the museum readymade – and especially one big gamble, i.e., make works of art that are in no way, on the face of it, adorned with the least artistic flourish, the least aura of (high or low) art. HH is embarrassed for he has already read that in the books bought by his father, and therefore he knows that you could say the same thing about dozens of artists who have come before him. So he says nothing to the curator in response and goes back down to his basement. When he opens the door, his girlfriend tells him, Either you become an artist or I’m leaving you. He repeats to her, half proud, half embarrassed, the words of the Tokyo curator, then shows her one by one all of the books bought by his father. She tells him, The important thing is not to be the first to do this or that thing, but to do as you are doing. So HH picks up his Bic and draws a mouse, a love mouse.

-Serge Bozon