Gülsün Karamustafa is a significant artist who has played a key role in the transformation of art in Türkiye over the past fifty years. She was a pioneer in developing a political poetics: asserting her freedom within the contemporary art world while providing a personal viewpoint and visual language regarding her countries’ realities. Drawing on a wide range of media combining figurative painting, video, photography, installation, and performance, her practice interweaves personal and political narratives that question the modernisation of her country as well as the concepts of origin, memory, migration, and identity.

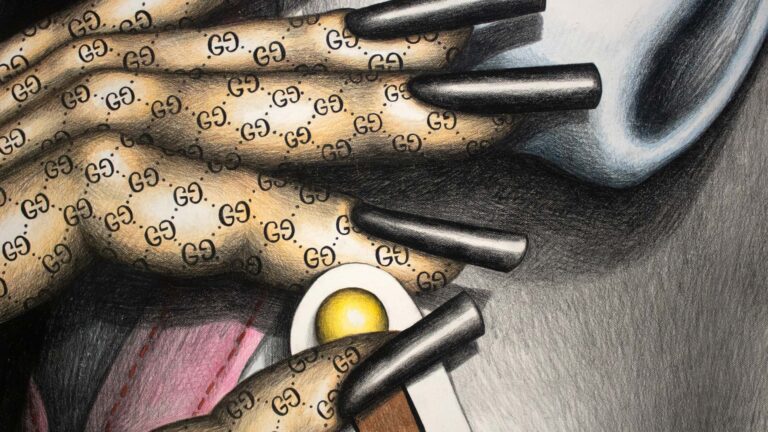

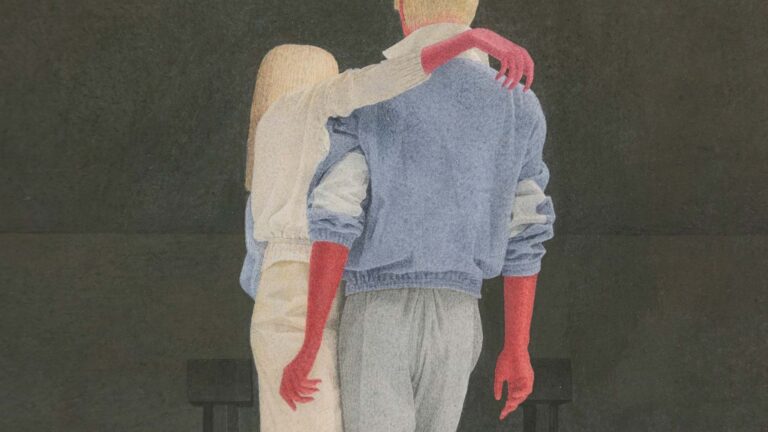

Taking social injustice as her premise, she draws attention to gender issues and the conditions of women in a patriarchal and post-colonial context. By constantly incorporating and interacting with spaces representing femininity and political subjectivity, Karamustafa has opened up new perspectives and opportunities for transformation, otherwise silenced by dominant narratives based on the ideas of progress or decline.

Hollow and Broken: A State of the World at La Loge follows Karamustafa’s presentation for the Türkiye Pavilion at the 60th International Art Exhibition – La Biennale di Venezia, 2024. The installation has been adapted for the temple’s space and comprises a selection of sculptures made from found materials, audio, and video. The artist offers us an insight into the current state of the world, where geopolitical, environmental, and social upheavals have led to a climate of instability and helplessness.

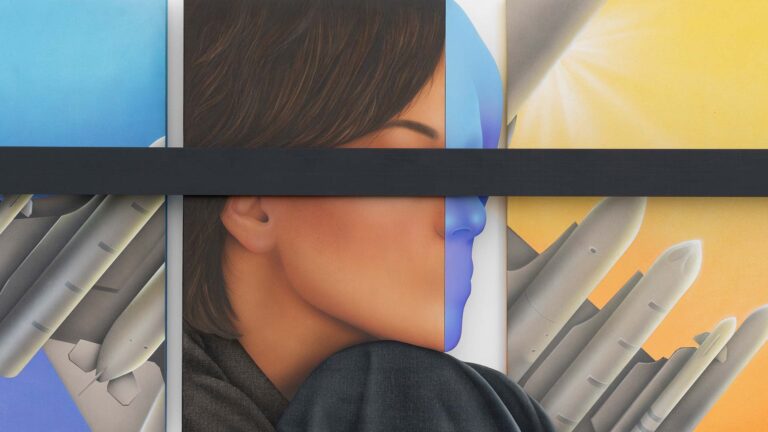

All narratives of ancient cities seem to rely upon columns. As well as their functional role, these architectural elements—featured prominently in La Loge—represent a certain tradition in construction, a visual culture, and a symbolic language. In the installation, however, the Corinthian columns crowned with capitals are none other than hollow moulds sourced by the artist from a Chinese supplier. Recalling the ruins of an archaeological site, these symbols of power can no longer stand alone and are propped up or protected by metal structures. The hollowed-out columns reflect the vacuity of certain civilisational development programmes, echoing a sense of history’s incompletion and failure. Both the plastic material and the serial, mass-market nature of the columns are evidence of an object transformed into a consumer item, bearing witness to the artist’s critical stance towards globalisation.

Through clouds of barbed wire, we see towering glass light fittings produced on the Italian island of Murano overlooking Venice, while the conglomeration of materials enveloping them catches our gaze. These works illustrate how glass is produced and the (dwindling) resources needed to produce it. The three chandeliers are, for the artist, a reference to the three monotheistic religions (Islam, Judaism, and Christianity), a theme taken up by Karamustafa in one of her earlier works: a long frieze featuring overlapping pages of manuscripts in a play on transparency (Trellis of my mind, 1998). Designed for Venice’s ancient Hall of Arms—where they were presented during the Biennale—the chandeliers’ splendour recalls the pomp and ostentation of military power in the medieval port city.

Oscillating between beauty and danger, fragility and destruction, the works play not only on contrast but also on hybridity. As is often the case in Karamustafa’s work, this style—inspired by objects in popular culture and bordering on kitsch—recalls the complexities of Turkish society “torn between different continents”, and of cities like Istanbul, shaped by successive transformation and the melding of traditions.

On the stage, Karamustafa presents a video produced using footage of demonstrations and international conflicts from different eras and geographical contexts, taken from the CriticalPast.com video archive. With no audio or clear narration, and no information concerning the videos’ sources, it is difficult to grasp the reality of these events. The nonhierarchical editing places particular emphasis on the humanitarian consequences, leaving the viewer helpless in the face of the plight of the fleeing or starving people he or she observes. Karamustafa operates like an archaeologist, uncovering political crises through these jarring images of distress.

The installation’s audio—conceived and designed in partnership with artist Furkan Keçeli—heightens the feeling of an indefinite timeframe, as do the other elements of the installation, all of which undergo constant change. Keçeli and Karamusfata researched which parameters were required to make the presence of short-term micro-movements perceptible. The sound, rather than a soundtrack to the video, relates to the installation as a whole and creates an abstract zone or a kind of turbulence connected to the other sculptural elements in the exhibition. The shards of broken glass, which symbolise both the threat of destruction and a sign of life, are echoed in the movements created by the looping and occasionally discordant noises. When seen from above the sculptural elements’ arrangement in space resembles a timeline, creating punctuations and unfolding alongside the audio cycle. Conceptually, the sound focuses on the chandeliers, which “struggle” to harmonise for a variety of reasons. Accordingly, the noises of breaking glass and water can be heard at the beginning and end of the loop, positioning them closer to an imagined surface.

The exhibition is organised in partnership with Moussem Nomadic Arts Centre as part of the festival Moussem Cities: Istanbul and in collaboration with BüroSarıgedik.

Gülsün Karamustafa is a Turkish visual artist and filmmaker born in 1946 in Ankara, who lives and works in Istanbul and Berlin. Through her art practice, spanning the course of over fifty years, she focuses on such topics as the modernisation of Turkey, uprooting and memory, migration, locality, identity, cultural difference and gender from an array of perspectives. Within her works, which stem from both personal and historic narratives, she champions the use of disparate materials and methods. Through media as diverse as painting, installation, photography, video and performance, she calls into question historical injustices in the social and political fields.

Karamustafa has participated in numerous international biennials, including Istanbul (TR); São Paulo (BR); Gwangju (KR); Kyiv (UA); Singapore, SG; Havana (CU); Thessaloniki (GR); Sevilla (ES). She has presented solo exhibitions at major institutions and galleries worldwide, including Salt Beyoğlu and Salt Galata, Istanbul (TR); Hamburger Bahnhof – Museum für Gegenwart, Berlin (DE); Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven (NL); IVAM Institut Valencià d’Art Modern, Valencia (ES); EMST National Museum of Contemporary Art Athens (GR); Kunstmuseum Bonn, Bonn (DE); Lunds Konsthall, Lunds (SE); Salzburger Kunstverein, Salzburg (AT); Kunsthalle Fridericianum, Kassel (DE); Museum Villa Stuck, Munich (DE), Centrale and ARGOS (with Koen Theys within the frame of Europalia) (BE), among others.

Her works have been included in the permanent collections of Centre Pompidou, Paris (FR); Tate Modern, London (GB); Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York (US); Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, Chicago (US); Musée d’Art Moderne, Paris (FR); Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven (NL); Hamburger Bahnhof – Museum für Gegenwart, Berlin (DE); Ludwig Museum, Cologne, DE; MUMOK, Vienna (AT); Wien Museum, Vienna (AT); Warsaw Museum of Modern Art, Warsaw (PL); EMST National Museum of Contemporary Art Athens, Athens (GR); Istanbul Modern Art Museum and Arter, Istanbul (TR).

She received the Roswitha Haftmann Prize in 2021 and Prince Claus Award in 2014.