If Giuliana Rosso were to launch a fashion line, it would be perfect for the worst imaginable skeletons in the closet—or at least the quirkiest—as her parade of garments, hung like laundry at La Tôlerie, well shows. Dracula’s rubber teeth sprout on a Gatorade cap, creepy masks pop out of pullovers, and a cringe green Huggy Wuggy comes alive on an equally colored, piss-stained pair of jeans. These are just a few examples of a new series of painted second-hand clothes tailored with the inclusion of a variety of vintage toys, avidly accumulated over early morning flea markets scavenges as well as late night Vinted hunts. It’s the first time that the artist paints on clothes, yet it comes as no surprise that it’s not on canvas where paint is to be found, typically accompanied by a series of numerous drawings on dusting paper, also pivotal within her practice. Painting, in Rosso’s clutches, is often pushed beyond its physical boundaries. It manifests in expanded forms; as site-specific interventions, or covering objects of various nature and papier-mâché sculptures. And even when more “classically” placed on canvas, thick layers of pigment spill over the edges, leaving jagged contours as if the paint were being propelled outward into space—defying gravity until there’s nothing left to hold it in place. On this specific occasion, figuration—pivotal in Rosso’s artistic expression at large—is treated in such a literal fashion that it tips into abstraction, as vivid monochrome brushstrokes leave the task of representation to actual objects, allowing for existential tones to emerge together with narrative ones. Analogously, the real is depicted in all its precarity, reaching irreal terrains where each one’s internal demons become disturbingly possible. It makes perfect sense, then, that a miniature Buffy’s flipper floats in a laundry basket, just as a series of cut-into-shape drawings of underwear give a personality to chastity, menstrual discomfort, wounded feelings or disinhibited sexuality: not fantasy nor surrealism, but reality made unstable, porous, and susceptible to emotional and psychological overflow.

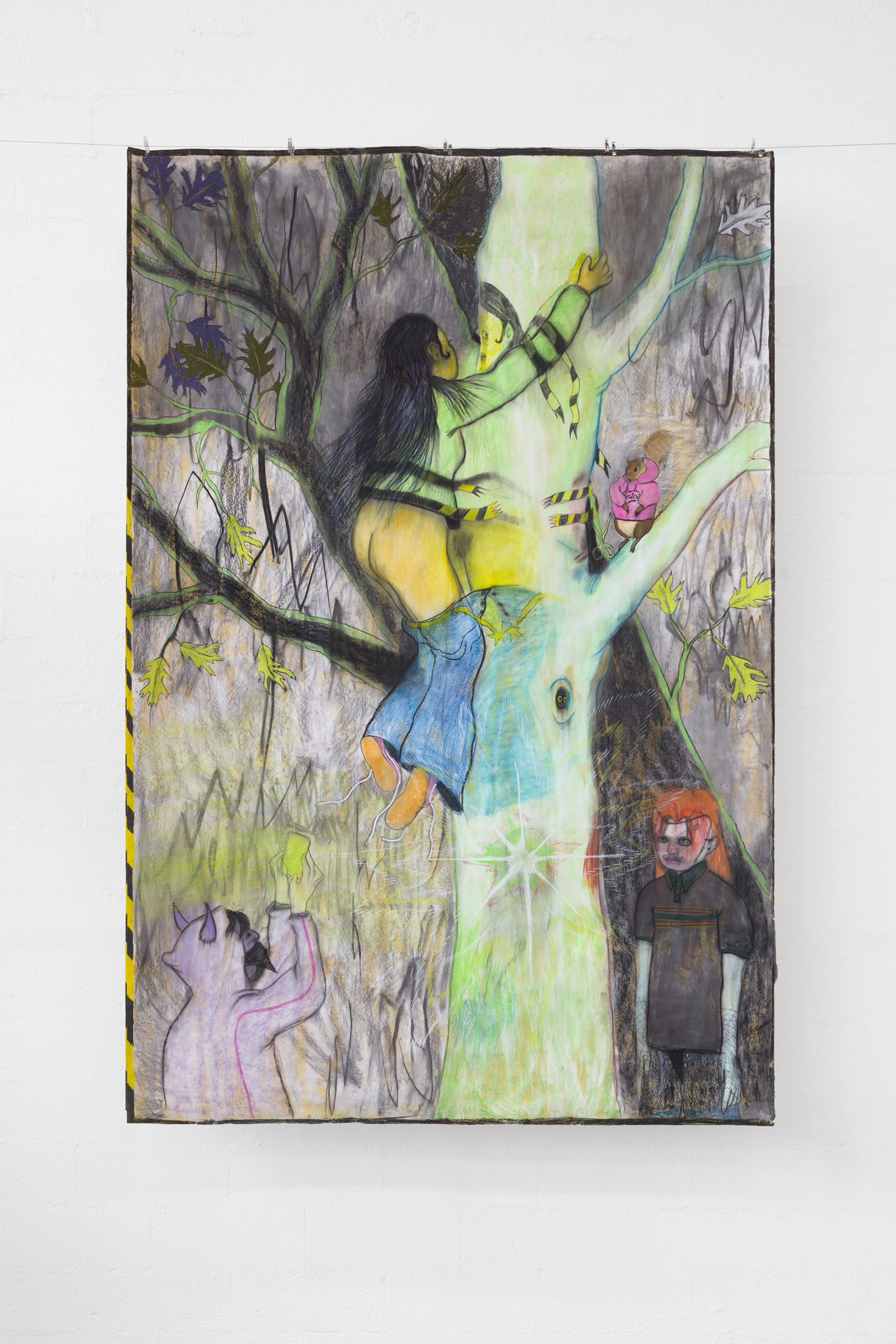

In Rosso’s universe, the everyday is cracked open just enough to let inner perceptions come into shape. Adolescence, in all its sensitiveness, is where the artist temporally and visually places her oeuvre, letting such a collectively shared phase of life become a potent metaphor for a human condition in which chaotic psychological clumps—of shame, aggression, desire, anxiety, or solitude—are told in all their frictional essence. It will be easy to notice visual references to 90s toys and 2000s early internet culture, as well as the depiction of young figures in states of vulnerability or introspection, who navigate a world where the deepest fears materialise and where what’s normally labelled as imaginary or supernatural manifest in moments of impotence. For instance, in Mouse Trap (2025)—the largest-scale chalk and charcoal drawing on dusting paper included in the show— a girl climbs up a tree’s mirroring bark. She has her trousers bent down and a preoccupied expression, visible from the reflection on the strange surface she barely holds to. Both the tree and the girl emanate a precious brightness that stands out precarious in a rather doomed environment, where two cruel figures wait devilishly. One will likely spot many other half-naked figures in the show, as well as references to genitalia. While there is a sense universality from Rosso’s tackling of sexuality and its taboos, ranging both irony and anguish, her androgynous figures also specifically expose the complexities of gender identity in ever more violent heteronormative environments, from current far right political orientations to family’s nucleus mindset, unveiling the fear and horror of not being able to come of age as queer or trans subjects. The same choice of proposing a hanging system inspired by laundry lines hints at a private dimension, traditionally domestic. In Italian, there is a common proverb, i panni sporchi si lavano a casa propria, indicating that the dirtiest and shameful aspects of life should not come out of one’s household. Here we are, back to the skeletons in the closet! Overall, the painted and drawn garments that fill the space become more than clothing: they are surrogate skins and bodies’ extensions, bearing traces of personal and collective testaments very much alive in all their hunting spectrality.

The motif of the double recurs frequently too, addressing the most untangled relations of self and other within settings, such as forests or bodies of water, which are perfect tropes for inner and intimate states. Possa qualcuno che non ho visto, che non vedrò mai (2023) is one of my favourite works ever made by Rosso. It shows a beautiful figure embracing another one, submerged in a spiral-shaped pond. The hug feels tender, melancholic. It’s intimate. There is a sense of quietness, perhaps an invite to trust and let go to the fluid, watery essence of emotion. The hairstyle and clothing of the two figures are identical, suggesting the two might as well just be one, while a six-fingered hand is a subtle acknowledgement of the imaginary nature of the scene. Its spontaneity offers a softness that is important to mention as lightness is, in fact, a key component despite the intense emotional terrain that Rosso covers. Her works range loosely across various artistic disciplines (collage, drawing, painting, sculpture), letting free expression candidly manifest in all its splendour. Here, clumsiness is beauty: wild and fragile like a blade of grass. There are guardians and protectors in the show, from the squirrel perched on the tree’s mirrored branches in Mouse Trap (2025), to the chicken-legged wine glass over a boy’s shoulders approaching the unknown in The World is a Vampire (2024). Even a mischievous mosquito on a starry blanket in Terapia (2025) acquires cute notes, bringing pep to the feeling of suspension that characterises the entire show. Among the few works that touch the floor, Muta di Basilisco (2025) is a giant Basilico’s discoloured shed skin flopping inert. As the king of all evil looks like a fading memory, it serves as a reminder that what Rosso brings forward is a site of recognition, rather than a battleground, dedicated to all that is repressed, unspoken, disallowed—yet alive, thus worthy of a name. We decided to personify all this as a group, under the name of The Hoverers. They are those who inhabit the most intimate dimensions, and that will make one feel naked, perhaps finally light. What words cannot express will be lived in the show.

—Caterina Avataneo