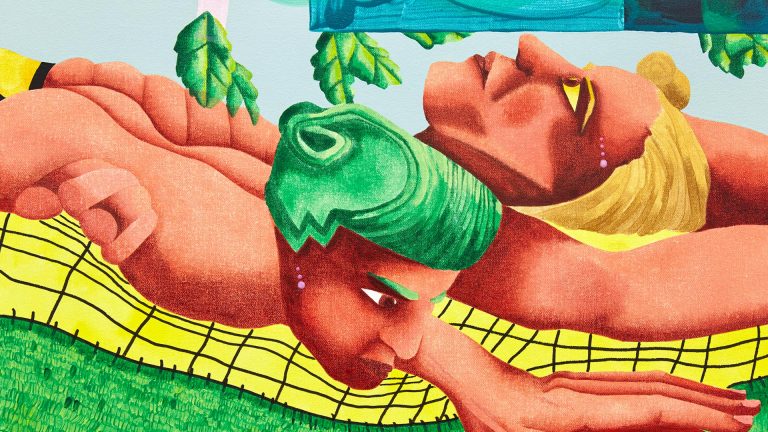

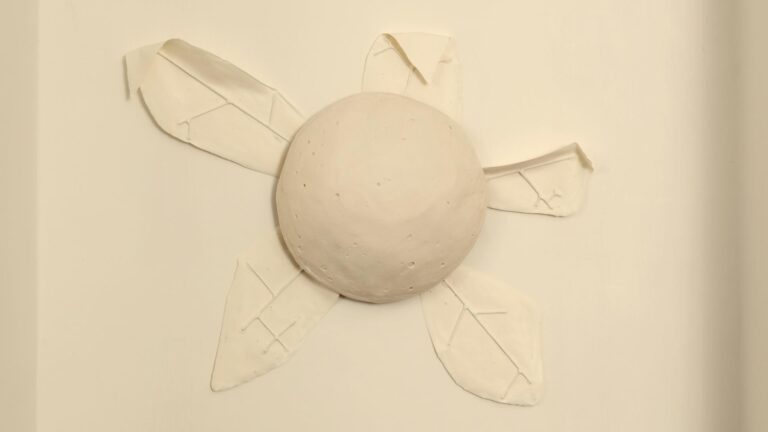

Artist: Gili Tal

Exhibition title: Civic Virtues

Venue: Cabinet, London, UK

Date: October 5 – November 10, 2018

Photography: all images copyright and courtesy of the artist and Cabinet, London

Note: Text by Oliver Corino can be found here. Exhibition floor plan can be found here

To imagine a city through the logic of capitalist relations you have to look awry. The spatialised arrange-ment of a city’s social order reveals itself as an uneven stratification of territory along antagonistic lines of class, race, gender and minoritised surplus populations. This social assemblage is precipitated by the relent-less need to create surplus value (more markets) combined with the forces of a control society that atomises and privatises the body politic, disarticulating the possibility for collectivization by the coordinated demands of extractive capital and the state. Subtle forms of civic violence often manifest themselves unwittingly, and even munificently as virtues, in the form of a public ‘gift’, a provision, a social good like parks, benches, playgrounds, clocks, bridges, bike lanes, street lamps: spatial objects we are taught to be thankful for. Infra-structure as such is both a utility and a means to reproduce unequal social relations. It is also a spatialized relation of power such that it facilitates ‘concrete social activity generating abstractions in consciousness’ in-cluding our very notions of the state, society and rights. These abstractions function dialectically as appara-tuses of capture and freedom, which, through their differing degrees of legibility, eclipse, distort and disguise each other through misrecognition, through an elective disregard.

But what if we misrecognise these abstractions differently? What if we look at urban spatial relations obliquely as a kind of collapse of state and private interests so omnipresent as to be almost invisible, as utterly banal? What kind of subjects are produced by these spatial relations and what are the relations pro-duced between them? Why do we give up certain freedoms and rights in exchange for certain protections, provisions and security? If the answer to these questions lies in the very formation of the capitalist state, then would it be correct to call the choices we make as subject-citizens under a moribund liberal democ-racy democratic? Is it not the very conditions of choice in their affective register– hopes, desires, fears and beliefs–where a truly revolutionary politics, an emancipatory ‘insurgent universality’, can be imagined and harnessed and where ‘communism will be the collective management of alienation’?