Artist: Giacomo Serpani

Exhibition title: Time Smoking a Picture

Curated by: Daria Miricola

Venue: Milliony Arlekina, Milan, Italy

Date: May 9 – July 9, 2024

Photography: all images copyright and courtesy of the artist and Milliony Arlekina, Milan

Note: Exhibition checklist is available here

As his eyes climbed the facade of working-class buildings, they poked around the trinkets behind dusty shop windows. Slipped under the coats of the old ladies walking before him and peered into the pockets of the men offering them their arm. Most of the time, our walks used to end up in a vortex of signboards, clocks, and laces corrupting the rules of good taste and would ultimately end by clumsily hitting my head.

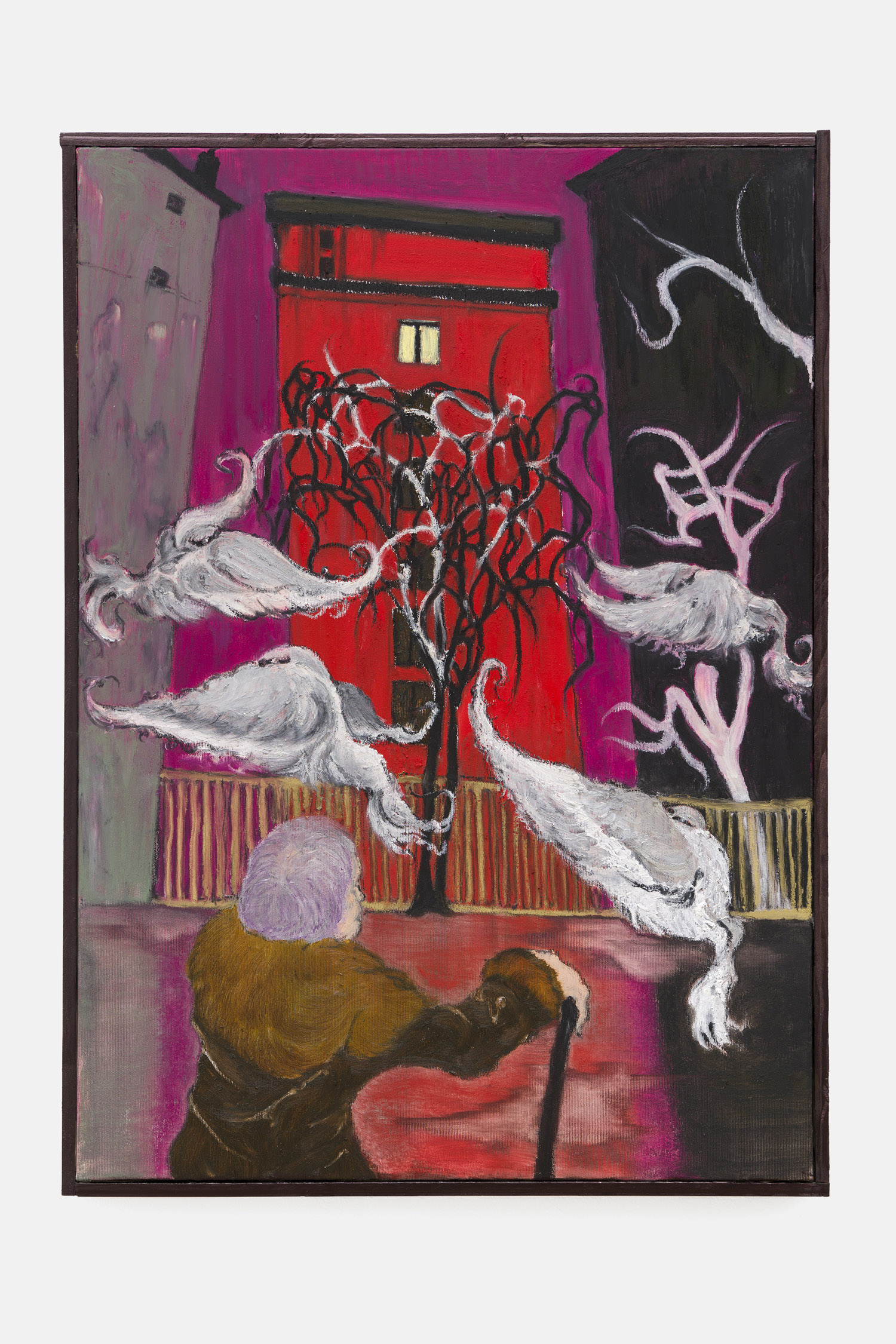

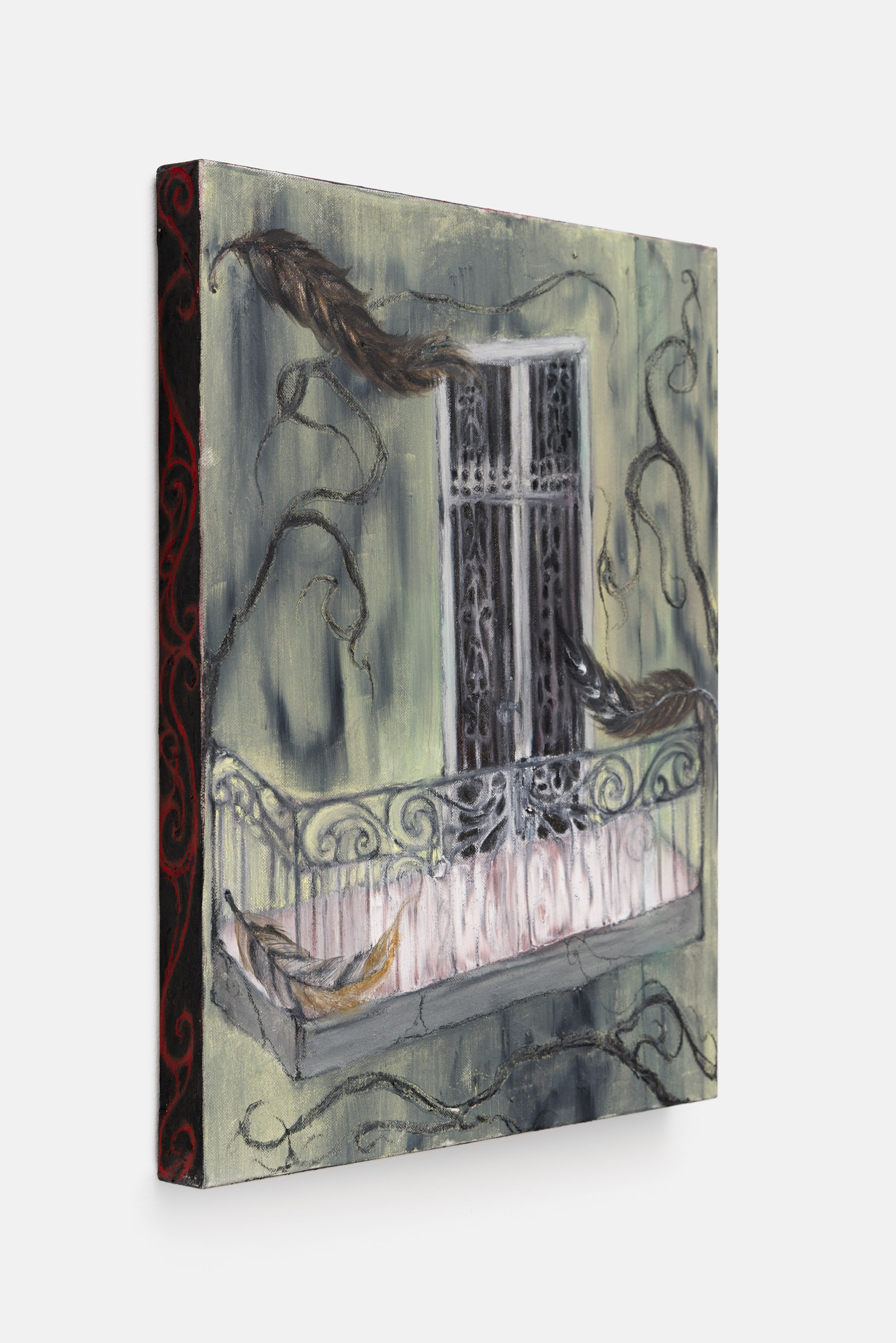

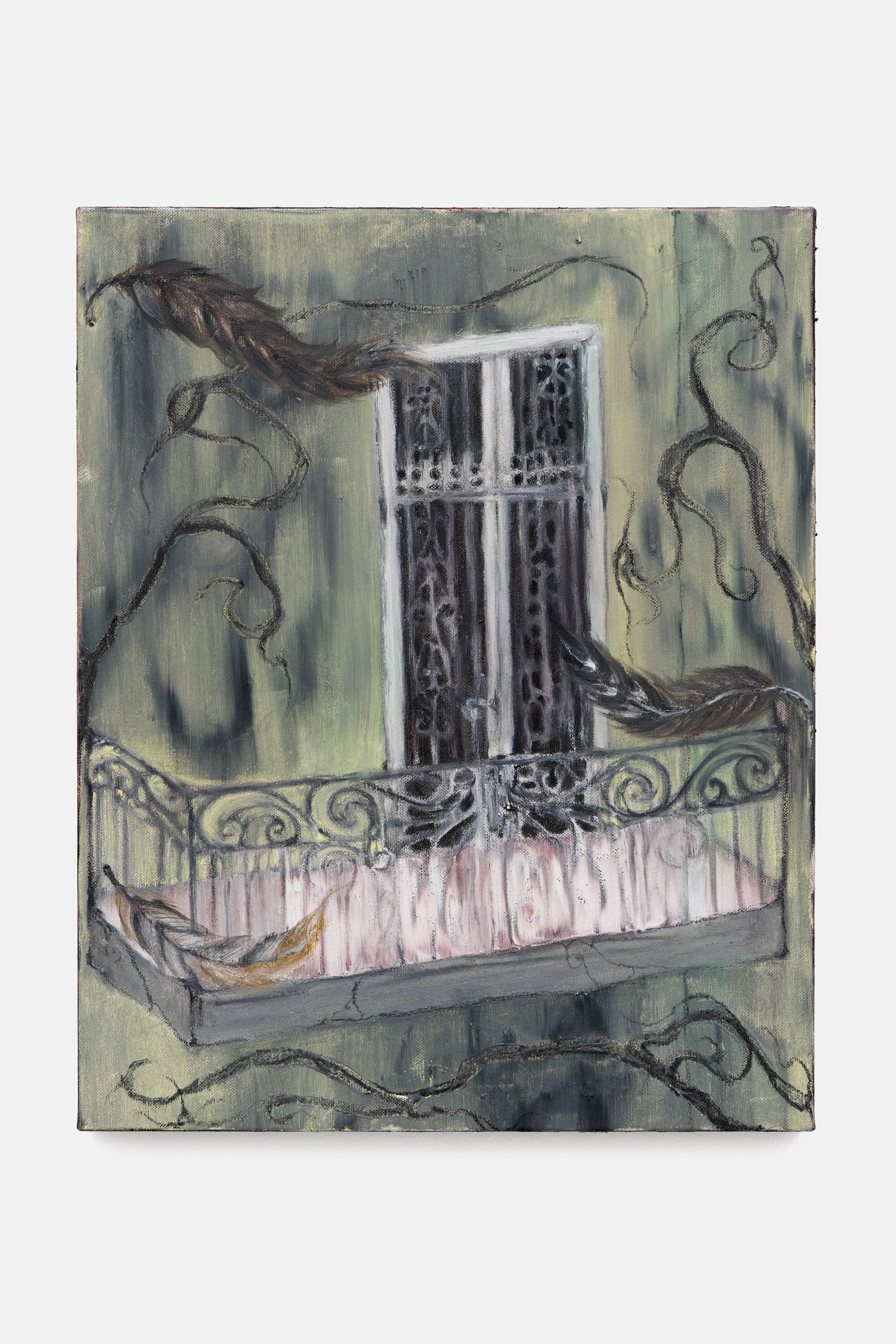

No subject was too insignificant or absurd to bewitch him, to inspire his witty observations and his quirky interpretations. And even if I still struggle to realize the mysterious code behind his treasure hunts, I eventually cozied up with the duality of his pictorial practice’s recurring idioms: decoration and decay. Decoration is a diva, a skin-walker with an ego complex, her baroque claws slip into every edge of representation, taking the shape of facades, clouds in the sky, or mutating into a bare tree like Daphne.

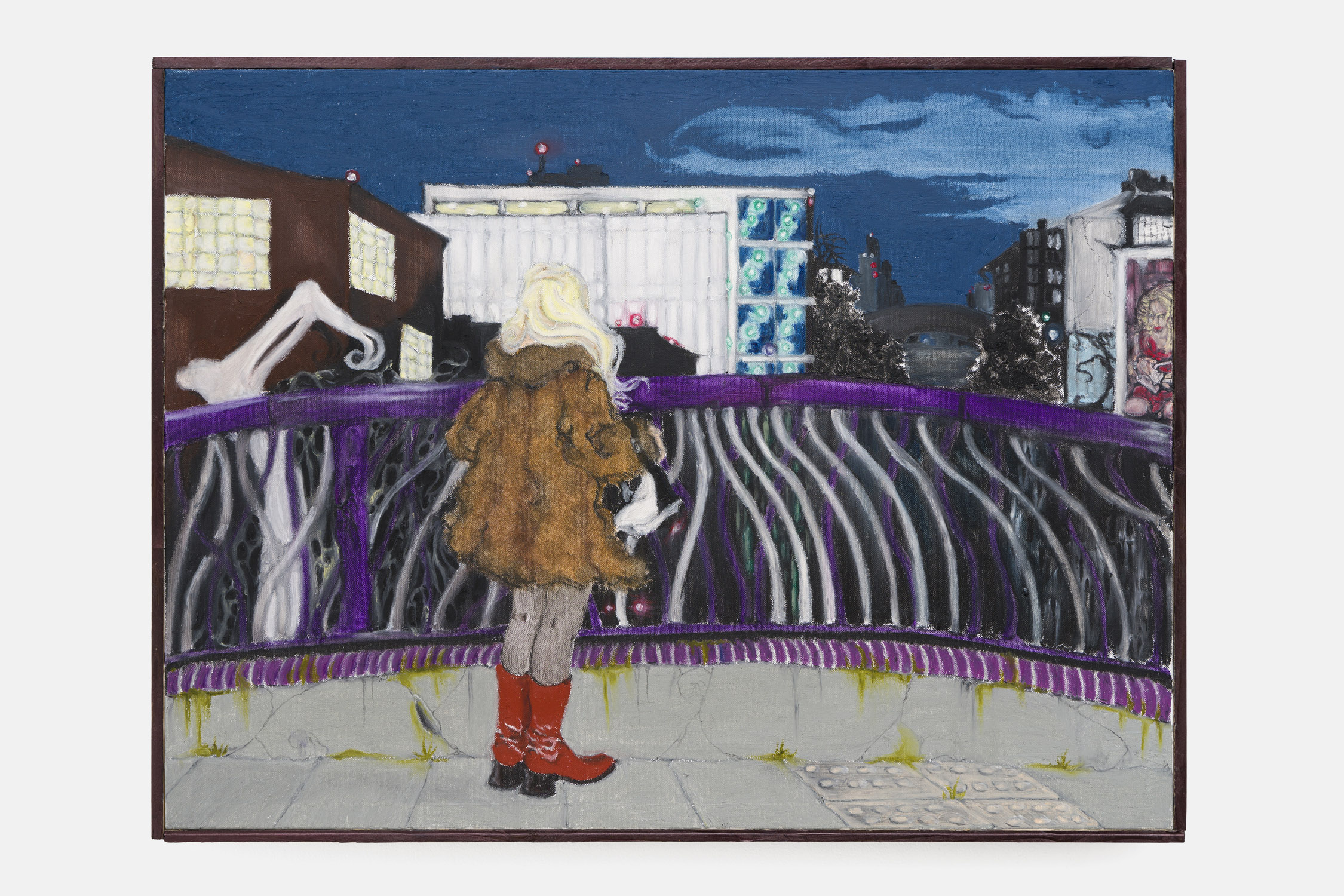

At first glance, this massive use of decorations recalls the attitude of a street cartoonist who approaches his subject through a lens of caricature and exaggeration, delighting viewers with its portrayals of city scenes crammed with folk energy and daily-life burlesque poetry. Yet, decoration is just a mischievous side of the coin that hides decay on its back.

It was the Russian poet Iosif Aleksandrovič Brodskij who first warned us regarding this dangerous duality through “Watermark,” a collection of essays dedicated to the city of Venice which we read last winter, while spending some days in his hometown Serenissima in Veneto. Brodskij writes about Venice’s tourists, who dress up with new clothes, jewels and a jumble of decorations in an attempt to emulate the style of the city. The more they try to merge into her picturesque scenarios, he notes, the more they highlight the difference between their bodies, imperfect and doomed to oblivion, with the timelessness of the city’s foundations among which they move. Similarly (but adversely and purposefully), the paintings exhibited employ a pictorial mannerism that aims at materializing notions of time, rather than deceiving the viewer through embellishment. Decay and decoration rage on the subjects, through their bodies, ornaments and surroundings. Like in Brodskij’s essay, they confront us with the idea that our awkward trophies and material belongings are the most discomforting reminders of our fleeting walk through life. As suggested by the typical Venetian mask—the one with the long beak-shaped nose—carnival and plague are the telling of a single story. Through his trademark series of swirls, decoration emblazons even human matter with the signs of its own decay, such as in Erion e Sua Madre (2024), where we see a detailed depiction of a crone’s sick and aging body, her sunken eyelids, and his drunkard son’s terrible complexion. Not only do their faces recall Venetian masks, but the whole scene conveys the same sense of decadence that is often associated with the city so accurately described by Brodskij, suggesting a common matrix between malice and malaise, bad habits and bad conscience, physical and spiritual corruption. I guess that the relationship he draws between decoration and decay is rooted in a very ancient paradigm. The art movement characterized par excellence by a zeal for decoration, i.e. mannerism, juxtaposes extravagance, preciosity, and abnormality, with a set of negative criteria as a loss of vitality, and the deterioration of public and personal morality.

In Spazio Beante (2024) decoration and decay exhale a metaphysical breeze into the atmosphere. As the skyline of Shoreditch gets rarefied within the passing clouds atop the roofs, the character’s emotional state seems to get nebulized in the cold air of the night. The ornate surfaces absorb any perception of time and space, ultimately unveiling the loneliness and the sorrow of the subject’s inner life. What seemed like a naïve approach to a scene of kitsch everydayness, adorned by amusement and whimsicality, suddenly reveals a deep introspection that drags us into a sense of dismay. Antigiallo (2024) looks like a flash-forward of Spazio Beante (2024) but, despite their similarities, I have the feeling that the former is way more optimistic. An elderly figure advances towards a burgundy horizon haunted by oversized baroque birds evoking an ominous composition. Like a broken spell, the characters seem unwilling to continue to entertain a fictitious narration that forces them to exist in the same plane. There’s a palpable eagerness to ascend into a composition where they can just be as forms, abandoning their terrestrial and figurative role to embody higher spiritual presences.

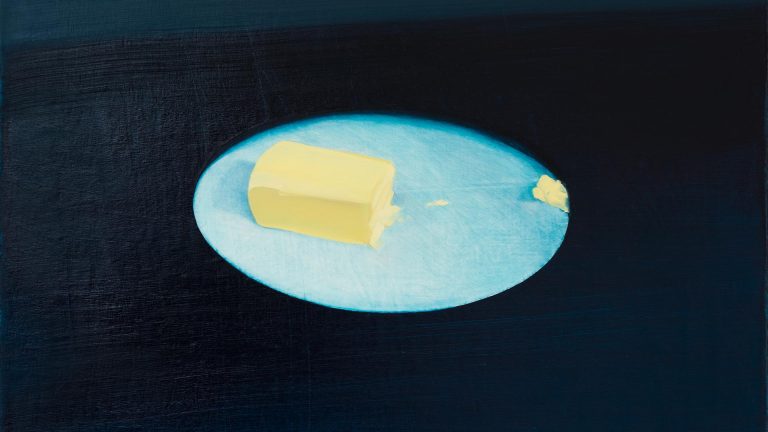

After writing this, I take a moment to think back on our walks. I guess that beyond good and bad taste, what truly interested him was detecting the personality of the objects around us, figuring out a way of representing them through new unnatural creations. I ponder how these would have freed his canvases from the regime of the pictorial clichés. Placing them in spaces that are impossible to populate and impossible to leave unfilled. Seeking beauty through an inner artistic reworking based on harmonic or rhythmical investigations. I guess sometimes, during our walks, we were starting to fade out into emotional abstraction as well.