Artist: Gheorghe Ilea

Venue: Galeria Plan B, Berlin, Germany

Date: February 19 – April 9, 2022

Photography: all images copyright and courtesy of the artist and Galeria Plan B, Cluj/Berlin

Galeria Plan B is pleased to announce the second solo exhibition of Gheorghe Ilea in Berlin, to open on Saturday, February 19.

TPP Zalău in demolition

The thermoelectric power plants used to produce high temperature and pressure steam by burning coal. This super-steam helps everyone. It gave us electricity, toiled away in factories and warmed us up in the winter, when there were months of cold and frost.

That’s what I understood from the explanations. What I experienced in the ’80s and ’90s, when this TPP was working, is a little bit different. It was cold both in the apartments and at the factory where I worked. There were only two hours of hot water in some days, well, where it could have come from? There was no cold water either, only for a few hours and then it was “taken”. The power was also taken. The people working at TPP told me that sometimes, many times, they received coal so bad it was rather dirt than coal. Some tenants “pricked” their radiators to get warm water. Almost all of them were clogged, the pipes too. I remember at one point, this was after ’89, in the block where we lived, we all changed our radiator supply pipes to wider ones, so that we get more heat. These stories are for those who haven’t lived them and who can rightly take them as a script for an absurdist movie. For a system to work, its parts have to fit each other. If the regime was wrong, people tended to choose tailored solutions. No, I wasn’t a rebel, I was an off-balance piece in an off-balance system. I mean, I ignored the environment as much as I could and I painted. Most of all I painted at the factory where I worked. Although generally fearful, I still used to walk out of the gate of the factory with works of 2 by 1.20 meters. One time I met with the director:

- What do you have there, Ghiță?

- A railcar of Diesel, comrade director.

And I was telling the truth, it was a painting: “Railcar with Diesel.”

Let’s get back to the paintings of TPP Zalău in demolition. The project aims to recover the recent industrial heritage by harnessing it in the space of contemporary art. Technology, computer systems, the way and methods of work, materials, innovation and adaptation to political requirements, the workforce, many things leave traces even in what is left of TPP Zalău, because when I painted it, part of it was already gone.

Leaving the language of “projects” aside, things went something like this: It was December 2013. I was going to plein- air, and not one day, but the whole month of December, which I do not recommend. I was working outside the city, I got near the TPP and I was painting the buildings from a distance. One day I stood in front of the entrance, about 100 meters away, next to a railway used only by the industrial area, I think there was also snow. After a while the guard comes to me, tall, dark uniform, dog and I think there was someone else with him, who stopped on the way. That was the last thing I needed. We were used to banned photography, but banned painting? I knew the TPP wasn’t working for a few years now. “Good day,” “What are you doing?”, etc. I have no idea what impression I made upon this man, nor what I looked like from a distance. I wore a dark green gown, one or two hats on my head, two pairs of pants and tights. I was sitting on a stool that I was carrying daily with me, a large black bag, the canvas that I held with my left hand, steadying it on my knees instead of an easel, and the other things: palette, colors, brushes, etc. After twenty minutes of work, water was starting to drip from my nose, after I finished painting the dripping stopped too. The guard says it himself: “Why don’t you talk to the bosses to let you work inside?” And that’s how it started. Not that beyond the gate was anything warmer, but I was covered, it was okay, I had approvals, I was a man who knew what he was doing and why he was doing it, I had a “project.” I felt like I belonged to the system, no longer stealing snipped images from afar, I could see them up close, from the inside, I was a man of the TPP. What I saw inside was a huge, huge amount of work, a type of oversized craft activity. There never has been a fair appreciation or payment of so much human effort gone into these megalomaniac constructions, from all historical periods, actually. Pipes of all kinds, welds also, sheets, glass wool around the pipes, wire mesh to hold the wool, joined galvanized sheets that wrap the pipes, taps, large and small, springs, concrete, reinforcing iron and two more pages of enumerations.

For two decades… And nature, which is slowly but surely reconquering its territory. Poplars growing everywhere, grass, weeds, bushes of thistles and blackberries. In the fall we would bring home blackberries from the TPP. Crows and other birds had a house there. I loved working at TPP, it was quiet. I was painting immersed in and absorbed by the images I chose. Large, rusty tanks, an entire fabric of pipes, solid concrete pillars, pierced ceilings through which the sky can be seen, like open mouths from which a few teeth have been extracted, and the vegetation that appears everywhere. In a large hall, once whitewashed, where there still is a pool with water, I made an exhibition, for myself and the pigeons that lived there. I changed the exhibition two, three times, every three months, and that’s not because of some concept, but it was much more practical to dry my paintings there, instead of bringing them home. There were also the towers, yes, they could be seen from afar. What will become of them, will they be wrecked? Or not?

In Bucharest, an engineer told me that their casting system, through a casing that moved slowly, without stopping, from the bottom to the top, while they were putting iron and concrete, is a Romanian invention.

The technology of building reinforced concrete towers does not belong to us, but erecting them continuously, without stopping, is a Romanian idea, and significantly reduced costs. Everything was centered on production. A few rhyming words, from a satirical show which was rehearsed in the factory’s club, ring in my head: “Take something from here, put something there, so the production goes on.” Everyone knew that was actually the case. I think that’s how they worked to build the TPP too, from morning until evening at the towers, and at night, without Saturdays and Sundays off. There had to be some kind of idealistic momentum, mentally it was better to get into the game. Some even thought what they were doing was important and pushed the envelope. The person was becoming ever smaller and unimportant; what really mattered were the great achievements. They worked like this maybe because of the ubiquitous propaganda, maybe the youthfulness, maybe… You may remember what Zalău was famous for at the time, the “plum brandy of Zalău.” Between you and me, it smelled to high heaven. Everyone in Bucharest expected you to get them plum brandy when you made a business trip there. At that time, we too were aware of article “402.” “The bosses drink, so we drink too.” I think there was also an article 400, which banned drinking at the workplace. On the concrete pillars you can still see, scratched into the wet cement, some dates, the day, the month, the year 1978, 1980, 1982. The flimsy green of chlorophyll quietly covers the turmoil of workers of old. Crows have their endless disputes. On a series of 70 by 50 cm works, made there, I painted a pair of crows on each canvas. Then I wrote in pencil their dialogue, which is simple: “YAA!,” “NEE!” And they keep debating the theme: whether the towers will be wrecked or not. They are very informed, up-to-date, even at the minute and very competent to debate this topic of maximum relevance and importance.

My paintings of the TPP are not “contemporary art.” It’s not what we’re concerned about right now, they’re not relevant, that’s how the painting was done 100 years ago, they don’t bring anything new.

Among the workers with TPP there was one who skirted the noisy present of the great deeds. He thought of his village, the hills, the trees in the garden, the grass. He had two scythes, one large, the “Dragon”, and a smaller one, the “Bee.” He liked mowing in the morning. How beautifully the dew on grass’s ears sparkled, when the sun rose. A rainbow formed when the scythe passed through the grass. He misses the rainbow.

-Gheorghe IleaGheorghe Ilea, born 1958, Bucea, Romania, works and lives in Zalău, Romania. Previous solo exhibitions include: Gheorghe Ilea: “Restoration process” 2015 – 2022. After “Exercise of humility” Tapestry of Ana Lupaș 1960 – 1962, Suprainfinit, Bucharest (2021); The Relocation Story, Plan B, Cluj (2014); Tronicart 1300, The National Museum of Contemporary Art / Dalles Gallery, Bucharest (2012); 10 Paintings, Plan B, Berlin (2010); PAUSA, Art Museum Cluj (2007); Collage, City Hall Gallery, Lorsch (2004). Previous group exhibitions include: După doisprezece ani. Producția artistică din România în 180 de lucrari. Expoziția Achizițiilor de Opere de Artă, MNAC – National Museum of Contemporary Art, Bucharest (2020); Mircea Cantor, Vânătorul de imagini, Musee de la Chasse et de la Nature, Paris (2019); DOUBLE HEADS MATCHES. A selection of contemporary artworks from four Romanian private collections, New Budapest Gallery (2018); KM/H. Utopies automobiles et ferroviaires 1913-2013, Tour 46, Belfort & Musee du Chateau des ducs de Wurtemberg, Montbeliard (2013); Figurative Painting in Romania 1970 – 2010, Romanian Cultural Resolution, Spinnerei, Leipzig, DE / Club Electroputere, Craiova (2010); Ad hoc – Romanian Contemporary Art, Ludwig Museum, Budapest (1997).

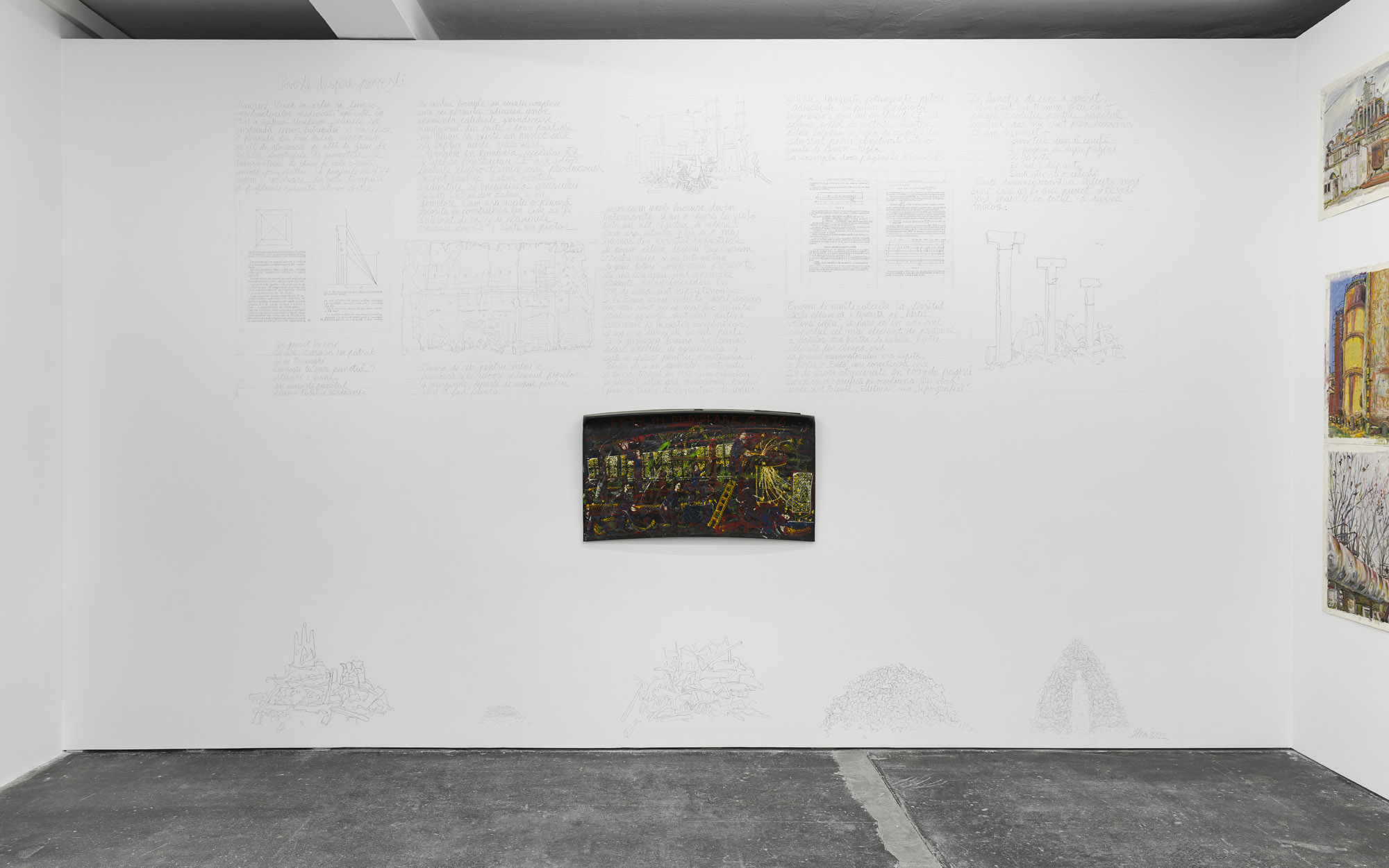

Gheorghe Ilea, solo exhibition, Plan B, Berlin, 2022, Photo: Trevor Good, Courtesy the artist and Plan B Cluj, Berlin

Gheorghe Ilea, solo exhibition, Plan B, Berlin, 2022, Photo: Trevor Good, Courtesy the artist and Plan B Cluj, Berlin

Gheorghe Ilea, solo exhibition, Plan B, Berlin, 2022, Photo: Trevor Good, Courtesy the artist and Plan B Cluj, Berlin

Gheorghe Ilea, solo exhibition, Plan B, Berlin, 2022, Photo: Trevor Good, Courtesy the artist and Plan B Cluj, Berlin

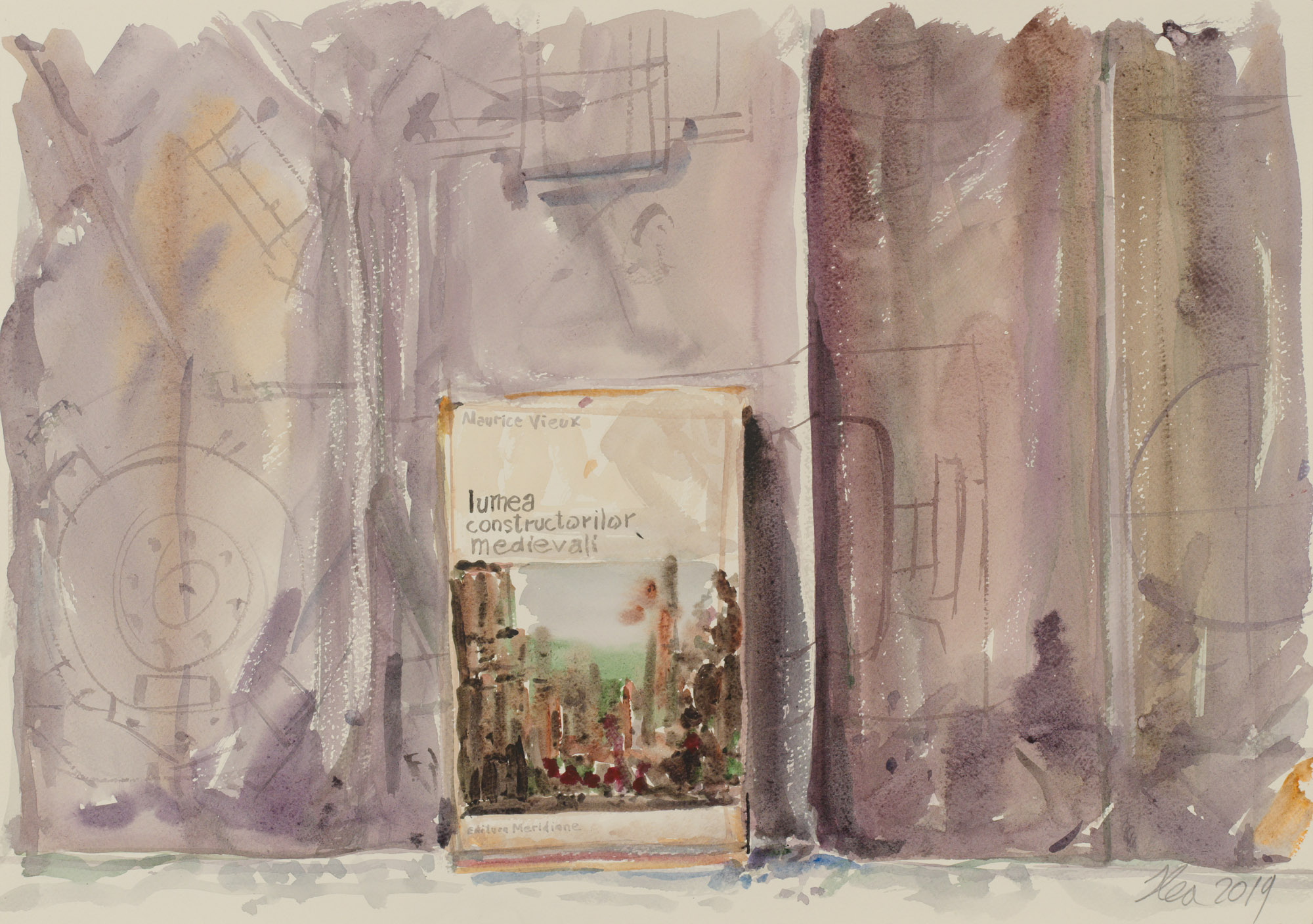

Gheorghe Ilea, Lumea constructorilor medievali (The World of medieval builders), 2019, watercolour on paper, 35 x 49 cm, Photo: Marius Poput, Courtesy the artist and Plan B Cluj, Berlin

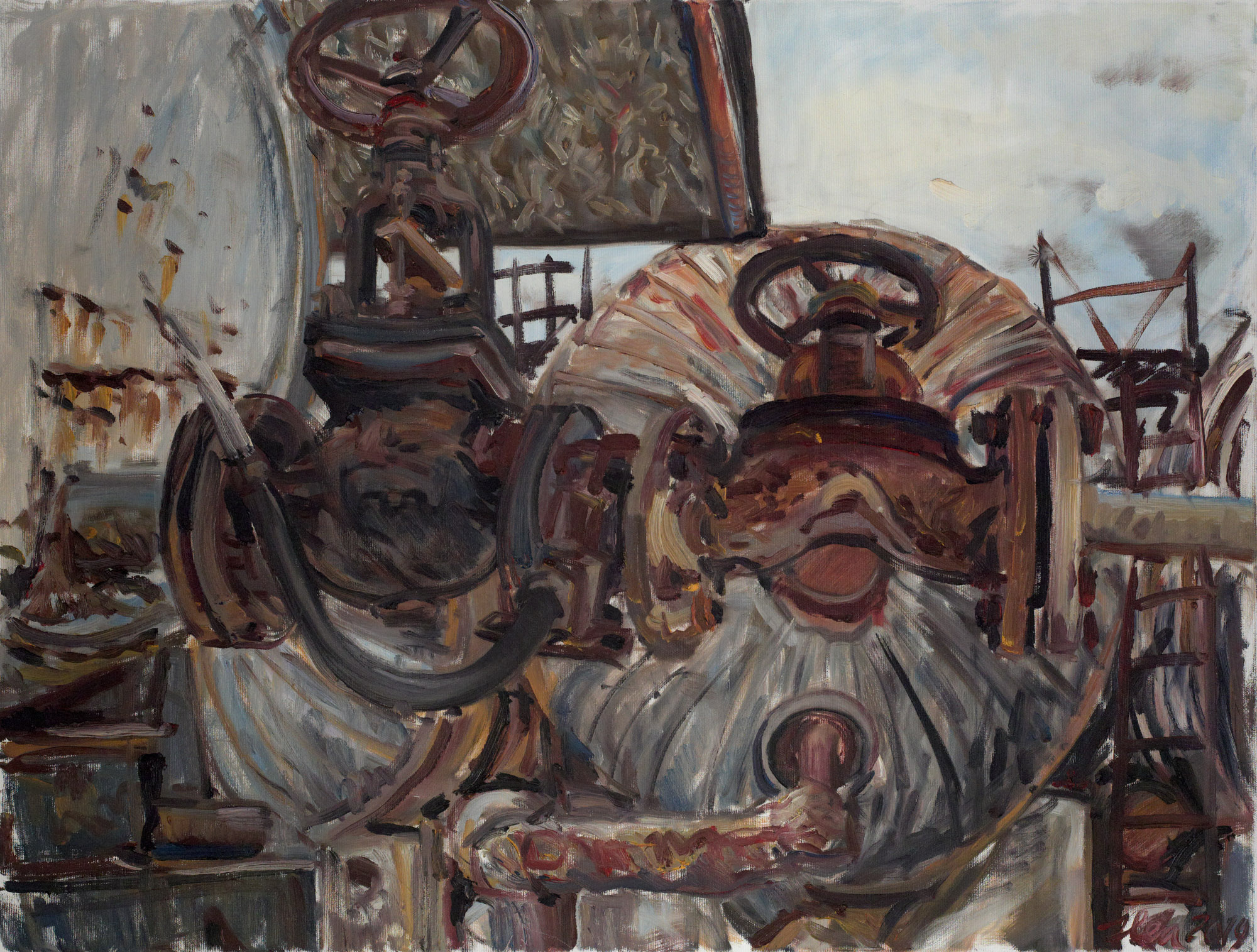

Gheorghe Ilea, TPP Zalau in demolition nr. 90, 2015, oil on canvas, 40 x 50 cm, Photo: Marius Poput, Courtesy the artist and Plan B Cluj, Berlin

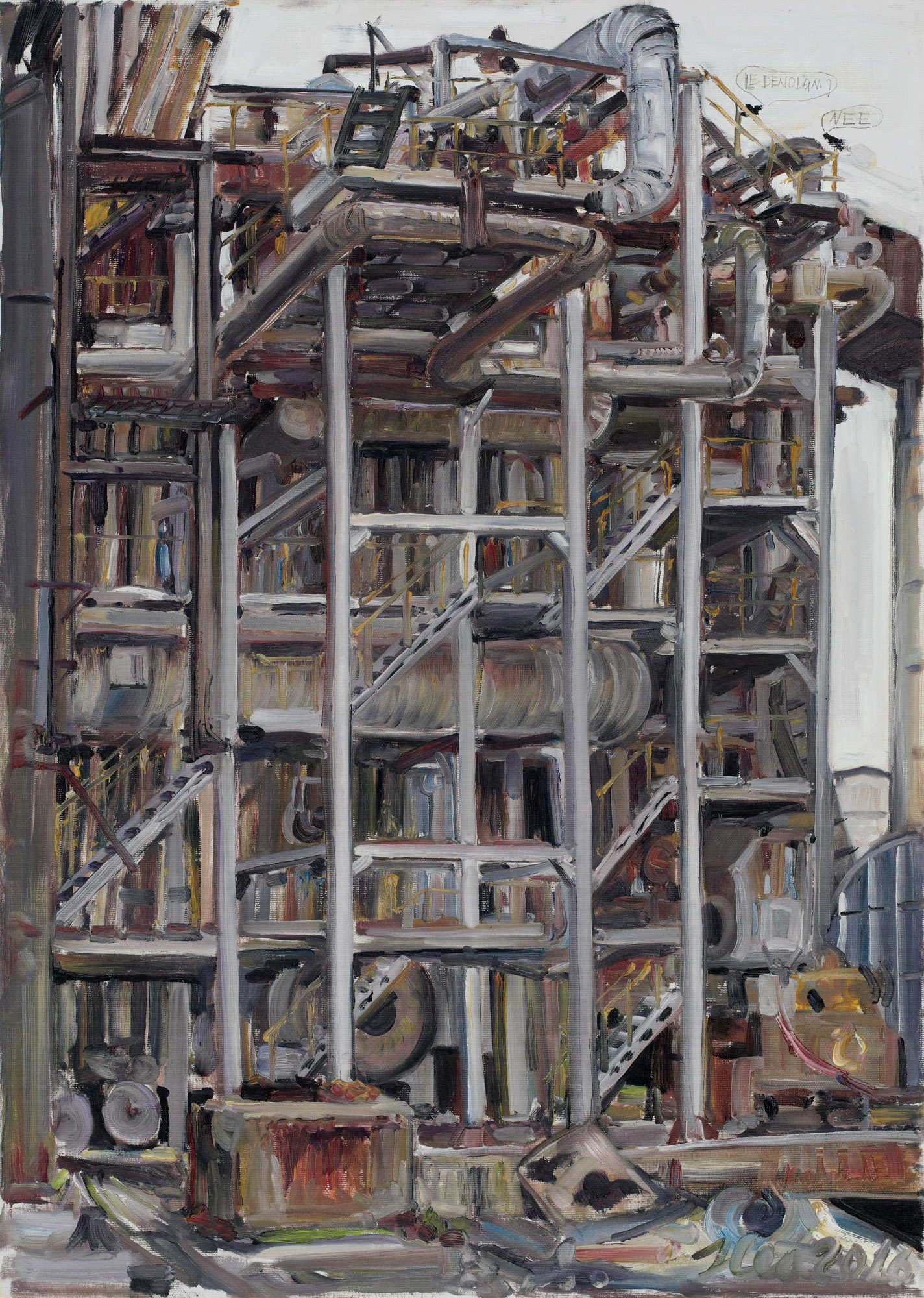

Gheorghe Ilea, TPP Zalau in demolition nr. 7, 2016, oil on canvas, 70 x 50 cm, Photo: Marius Poput, Courtesy the artist and Plan B Cluj, Berlin

Gheorghe Ilea, TPP Zalau in demolition nr. 68, 2019, oil on canvas, 60 x 80 cm, Photo: Marius Poput, Courtesy the artist and Plan B Cluj, Berlin

Gheorghe Ilea, TPP Zalau in demolition nr. 61, 2019, oil on canvas, 60 x 80 cm, Photo: Marius Poput, Courtesy the artist and Plan B Cluj, Berlin

Gheorghe Ilea, TPP Zalau in demolition nr. 33, 2019, oil on canvas, 80 x 60 cm, Photo: Marius Poput, Courtesy the artist and Plan B Cluj, Berlin

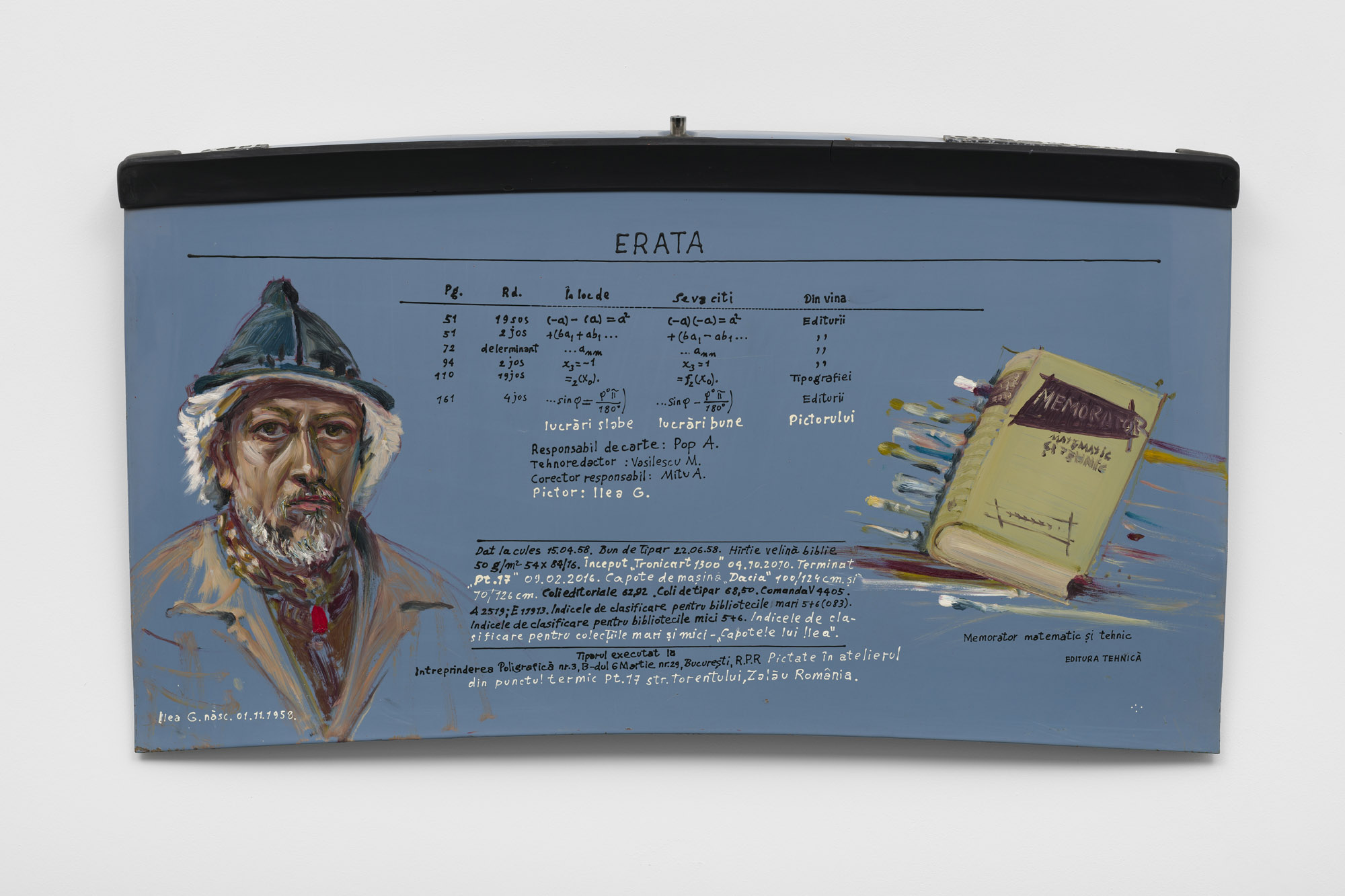

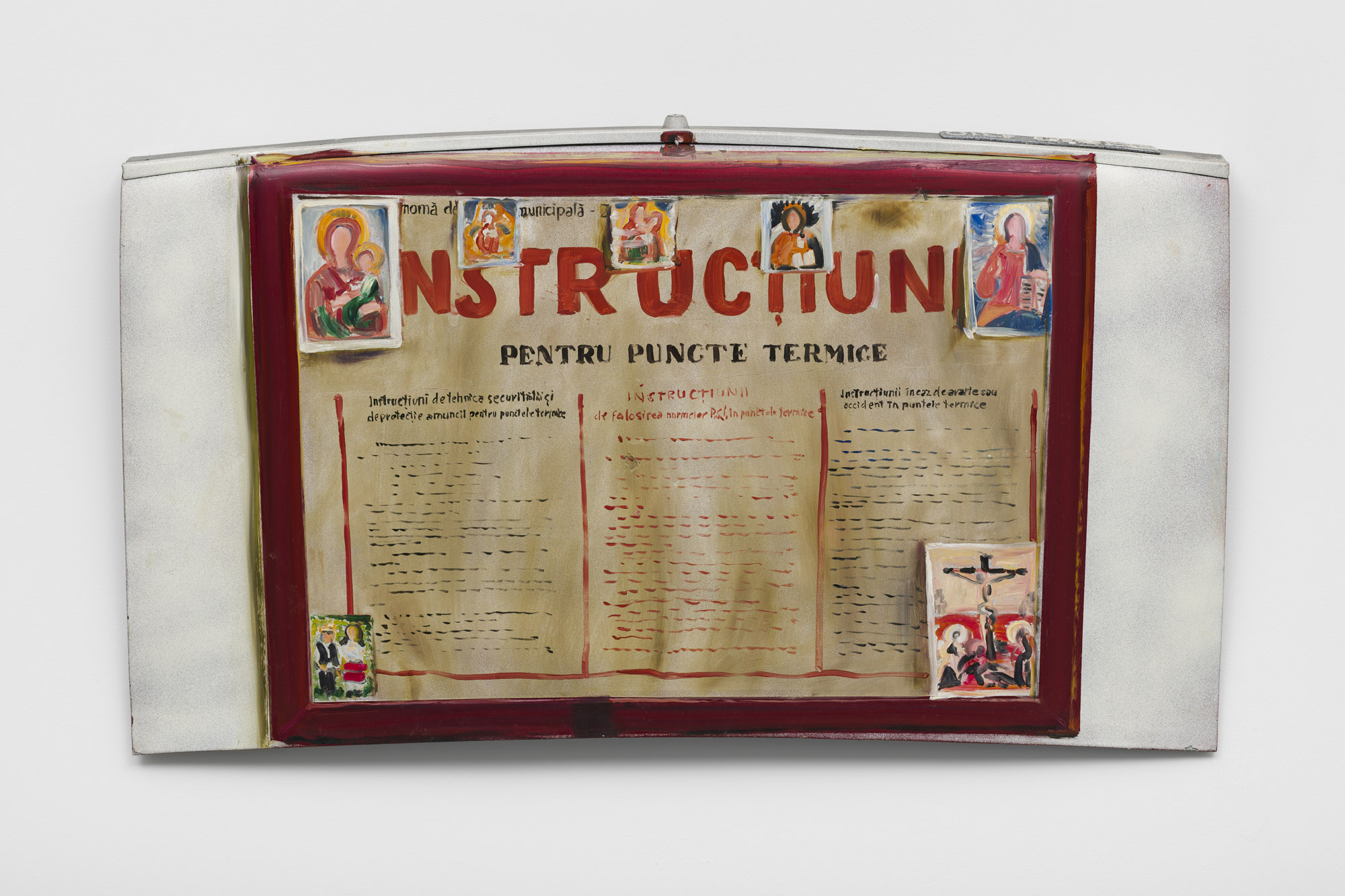

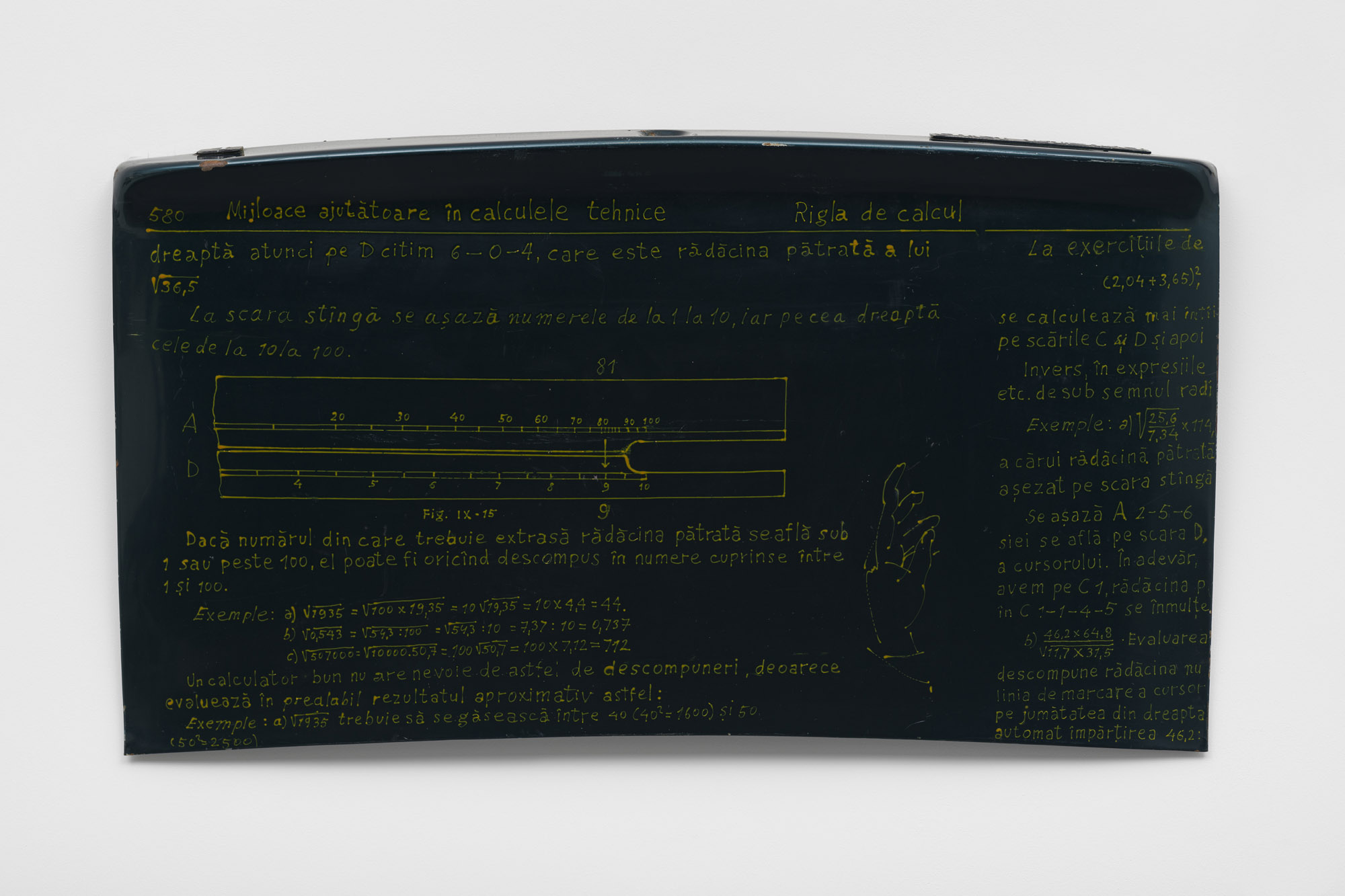

Gheorghe Ilea, PT 17 in demolare XVII (PT 17 in demolition XVII), 2016, oil on car hood, 74. x 126.2 x 11.8 cm, Photo: Trevor Good, Courtesy the artist and Plan B Cluj, Berlin

Gheorghe Ilea, PT 17 in demolare XIII (PT 17 in demolition XIII), 2016, oil on car hood, spray paint, 74.8 x 126.8 x 7 cm, Photo: Trevor Good, Courtesy the artist and Plan B Cluj, Berlin

Gheorghe Ilea, PT 17 in demolare XI (PT 17 in demolition XI), 2016, acrylic on car hood, 71 x 126.2 x 10.3 cm, Photo: Trevor Good, Courtesy the artist and Plan B Cluj, Berlin

Gheorghe Ilea, PT 17 in demolare XII (PT 17 in demolition XII), 2016, oil on car hood, 72 x 127 x 10.7 cm, Photo: Trevor Good, Courtesy the artist and Plan B Cluj, Berlin

Gheorghe Ilea, Mormanul de Balegar (The Dung Heap), 1994, video, 00:03:05, Photo: Trevor Good, Courtesy the artist and Plan B Cluj, Berlin