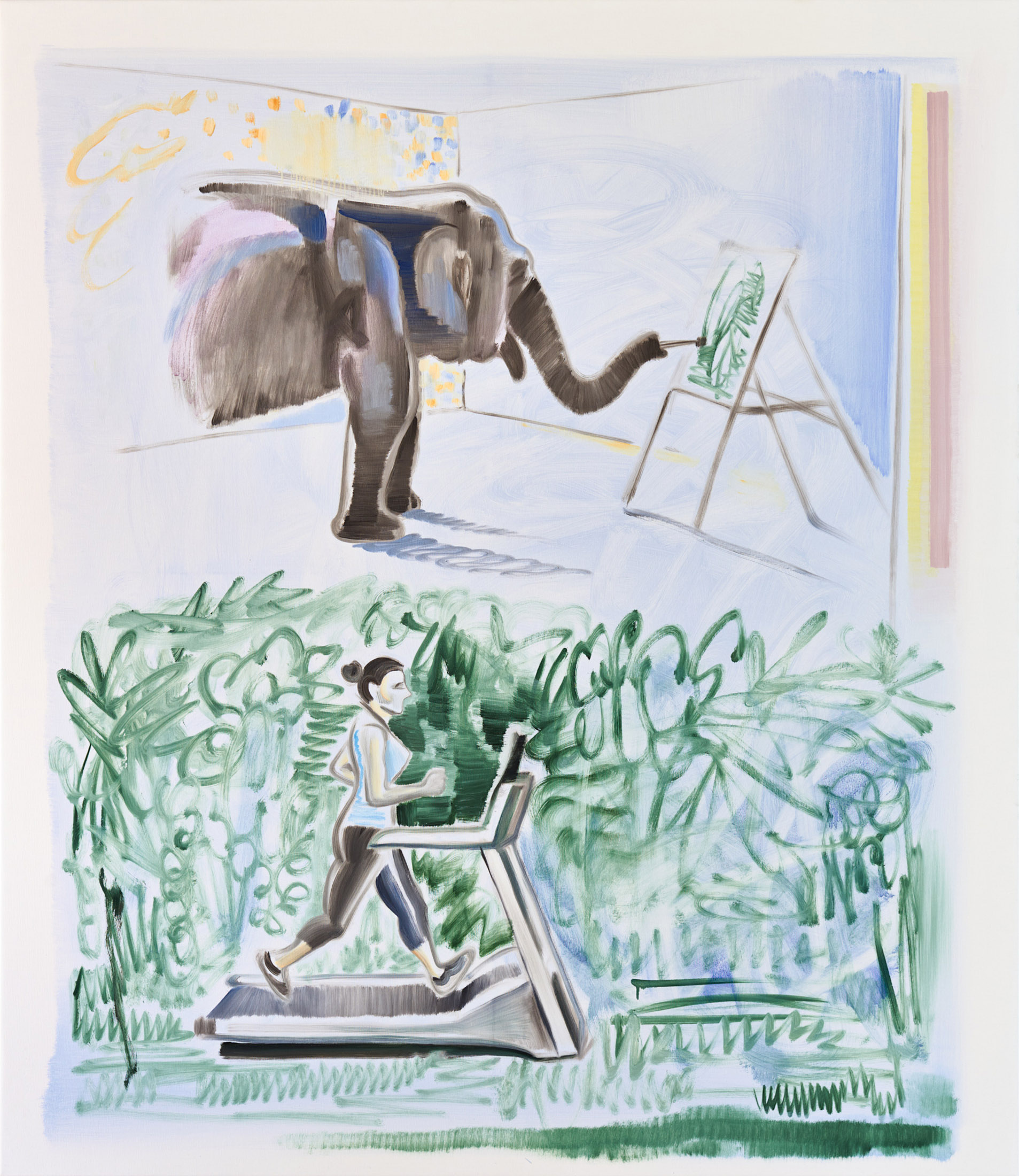

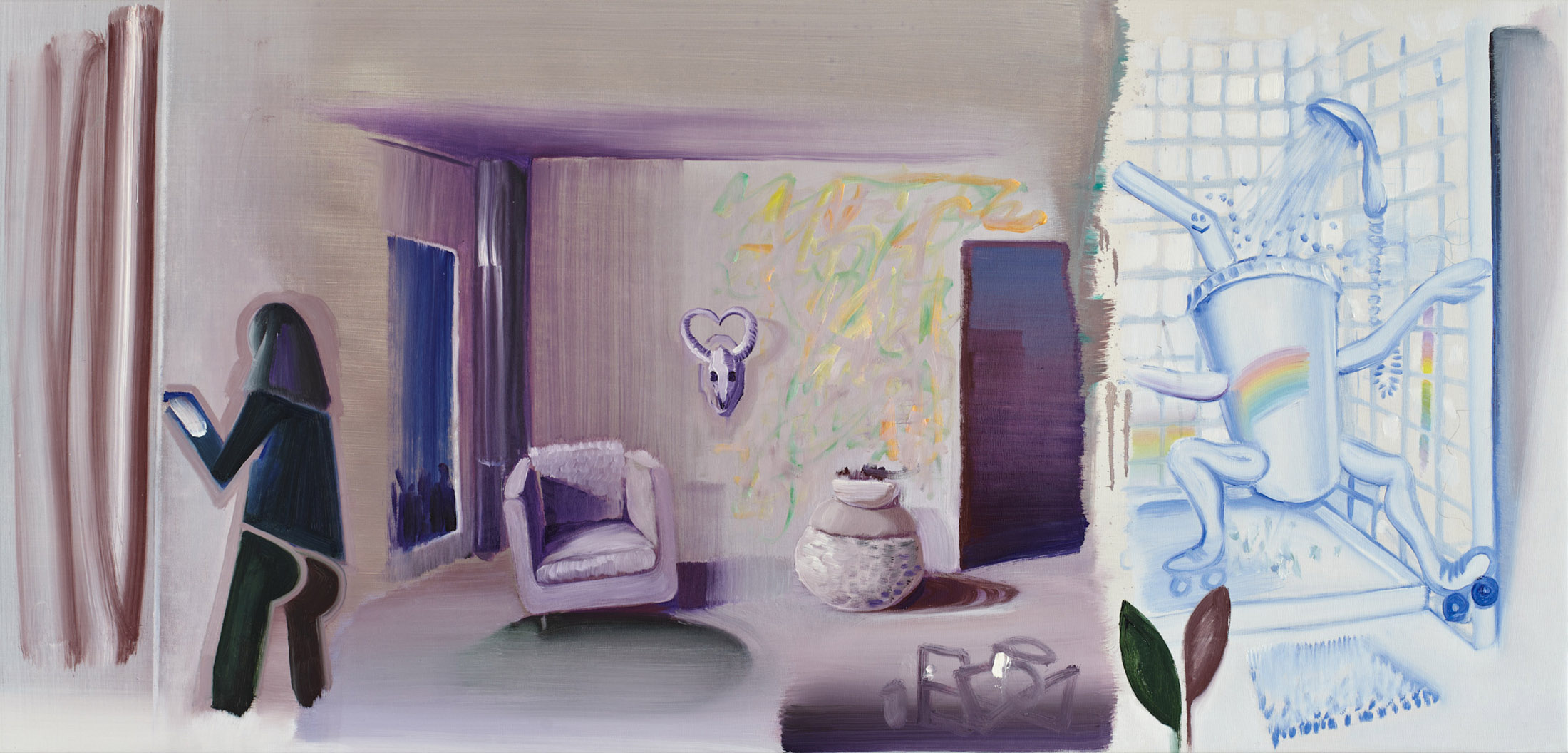

Artist: Gábor Pintér

Exhibition title: Sensational Nothing

Curated by: Peter Bencze

Venue: Longtermhandstand, Budapest, Hungary

Date: May 24 – July 7, 2023

Photography: Áron Weber / All images copyright and courtesy of the artists and Longtermhandstand

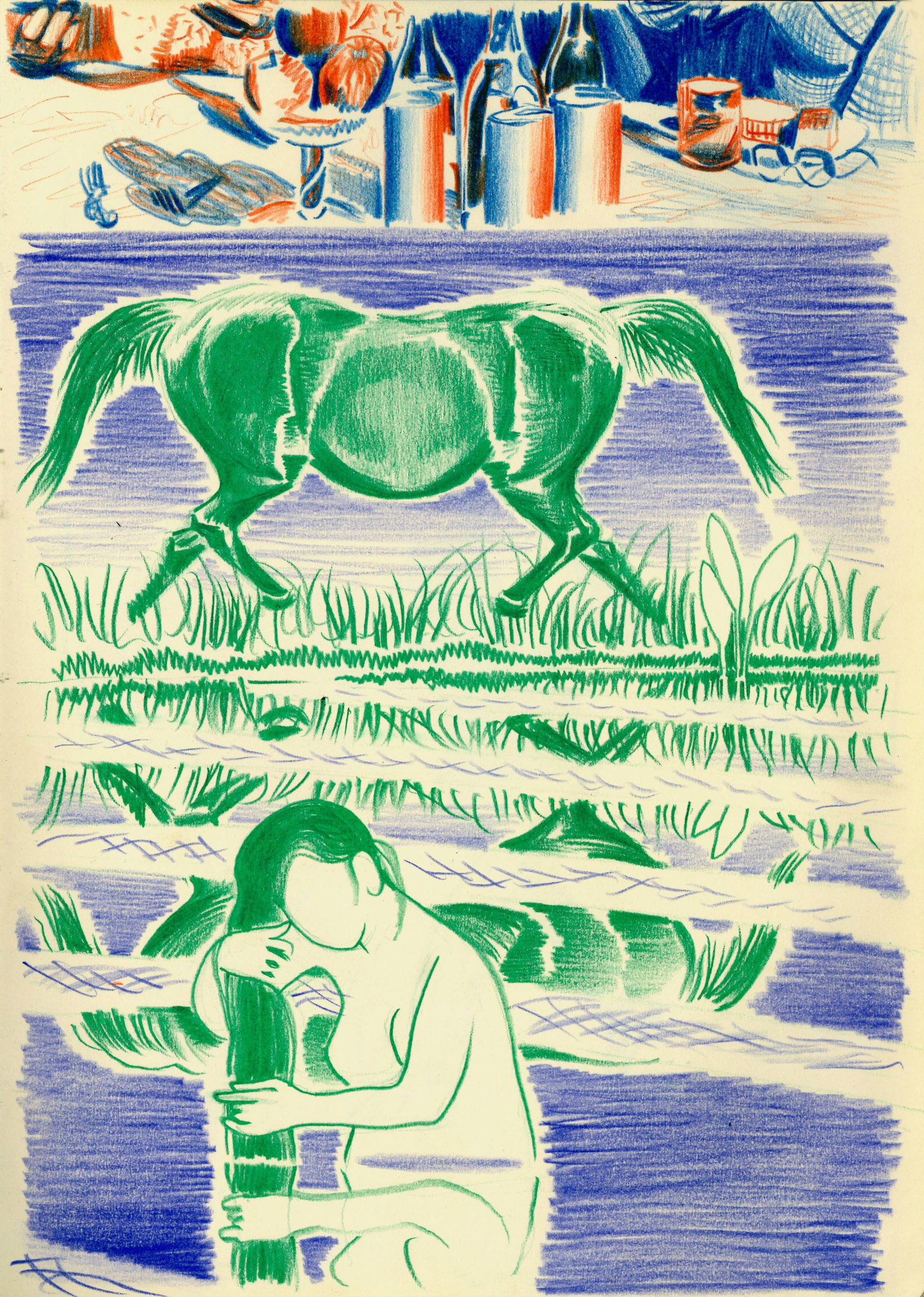

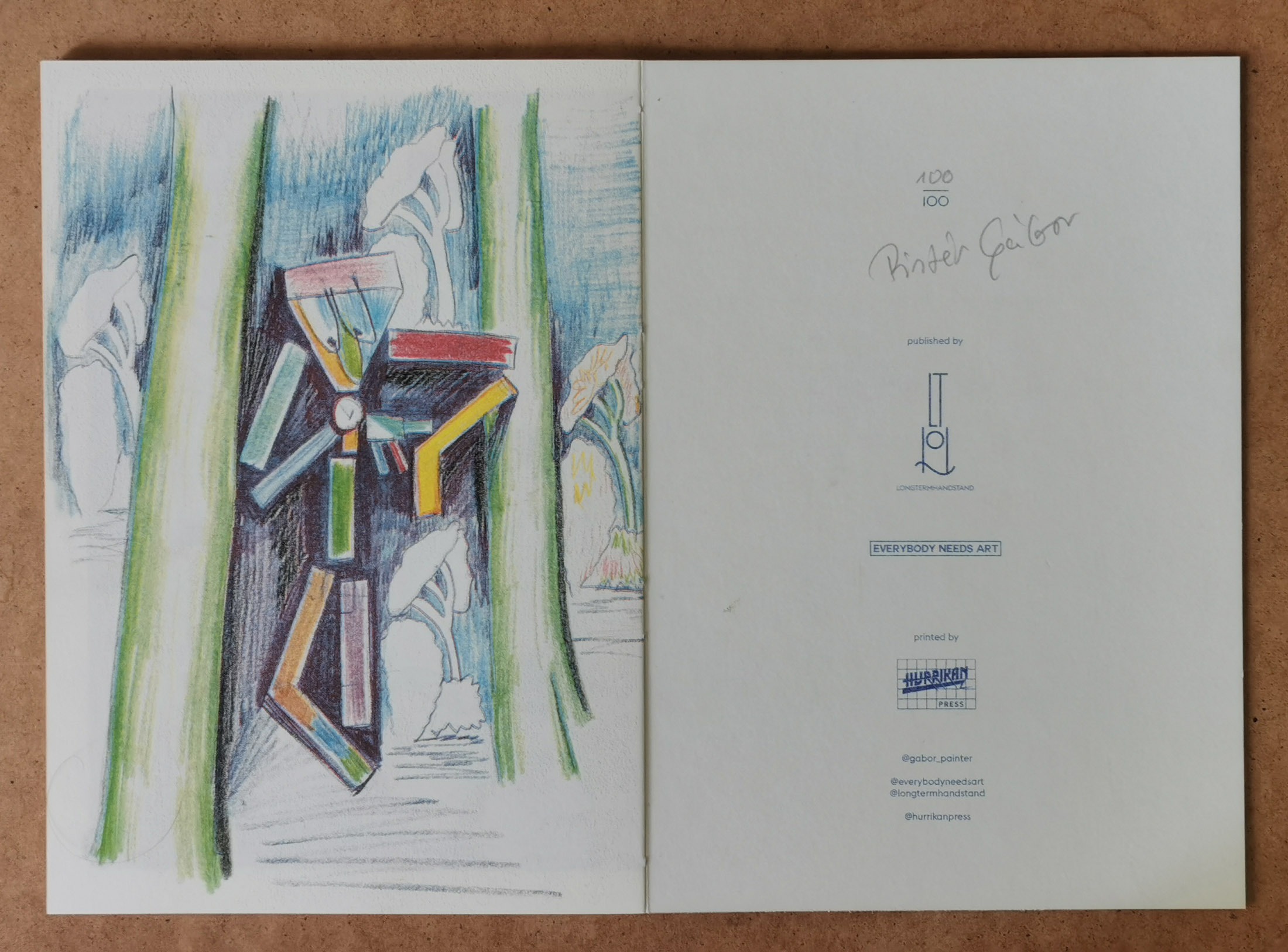

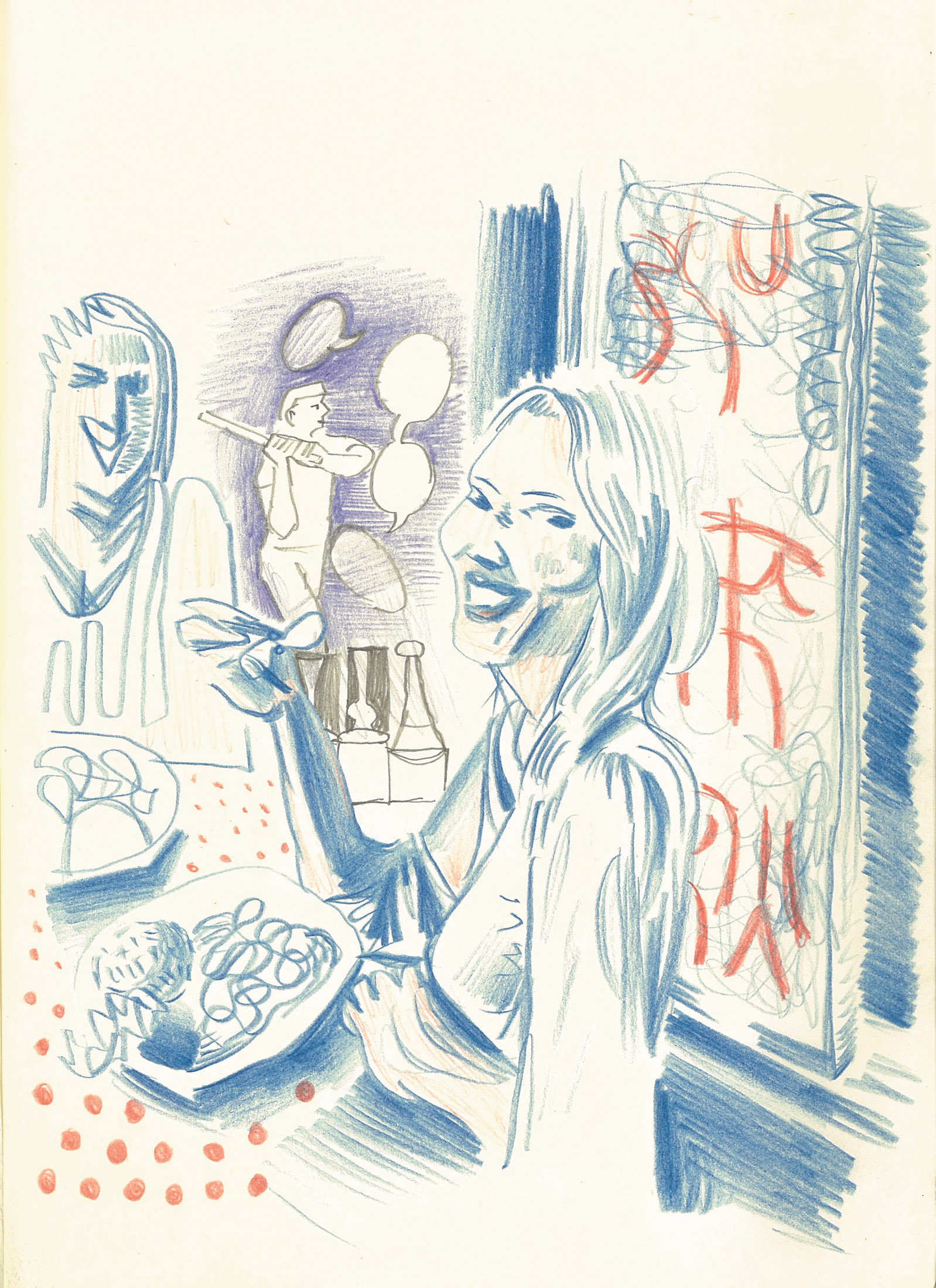

BF (Benedek Farkas): Your recent artist book, published in collaboration with Hurricane Press and Longtermhandstand, focuses exclusively on your drawings. What role does drawing play in your art practice, and how do your drawings relate to your oil paintings?

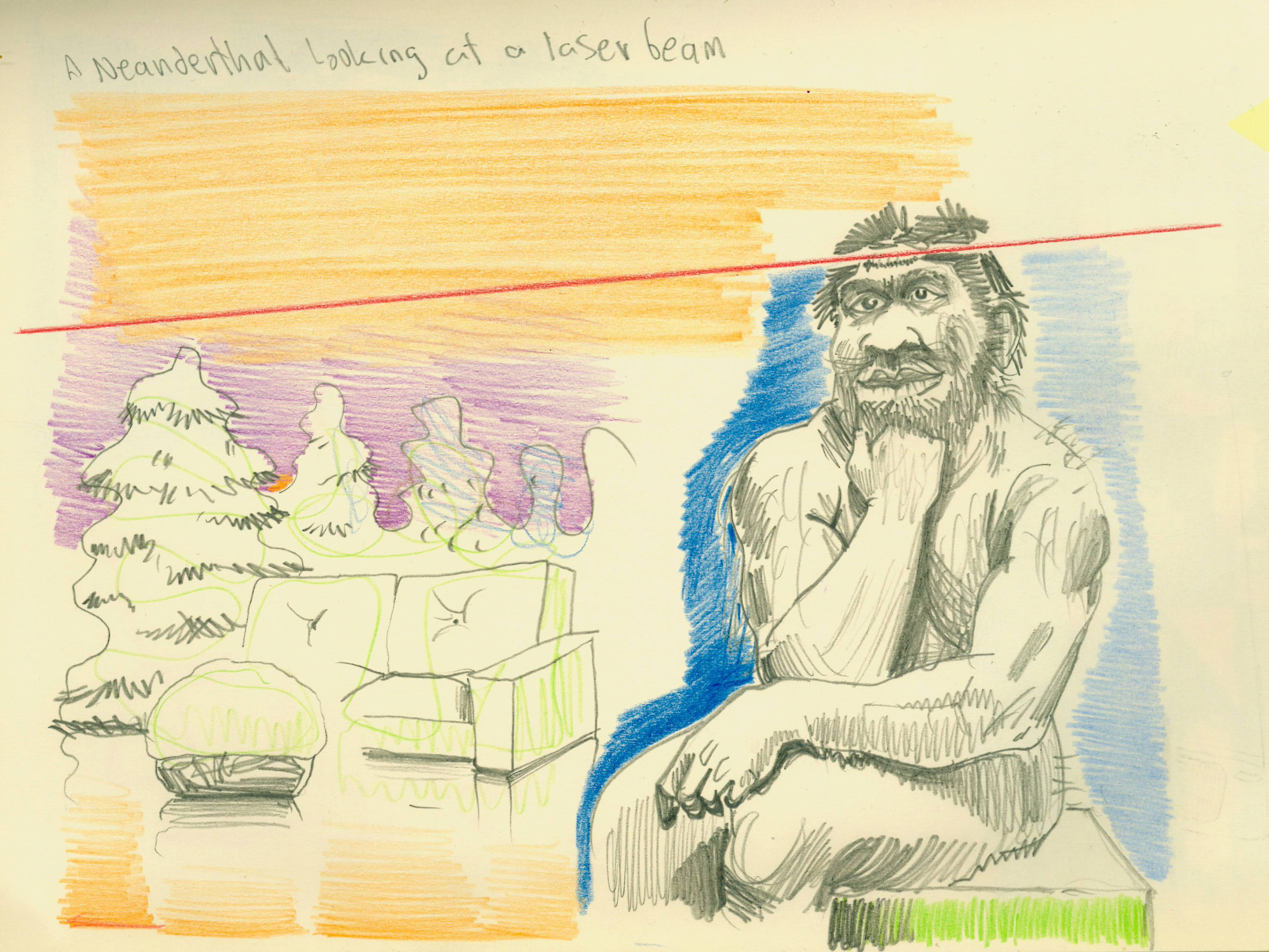

GP (Gábor Pintér): I have always been more of a drawer. I started painting more seriously only at the University of Fine Arts, where I developed a painterly approach or technique based on more drawn, line-like gestures. I use more sketchbooks, but not necessarily for sketching, of course sometimes sketches are created that way. Usually, if I have an idea, I sketch it, even if that works never turns into a painting. So these sketchbooks also function a bit like diaries. I approach a drawing in a completely different way than a painting, because it requires a completely different way of thinking. When I try to translate a drawing into a painting, I have many difficulties and I don’t always succeed. So my drawings are relatively independent of my paintings.

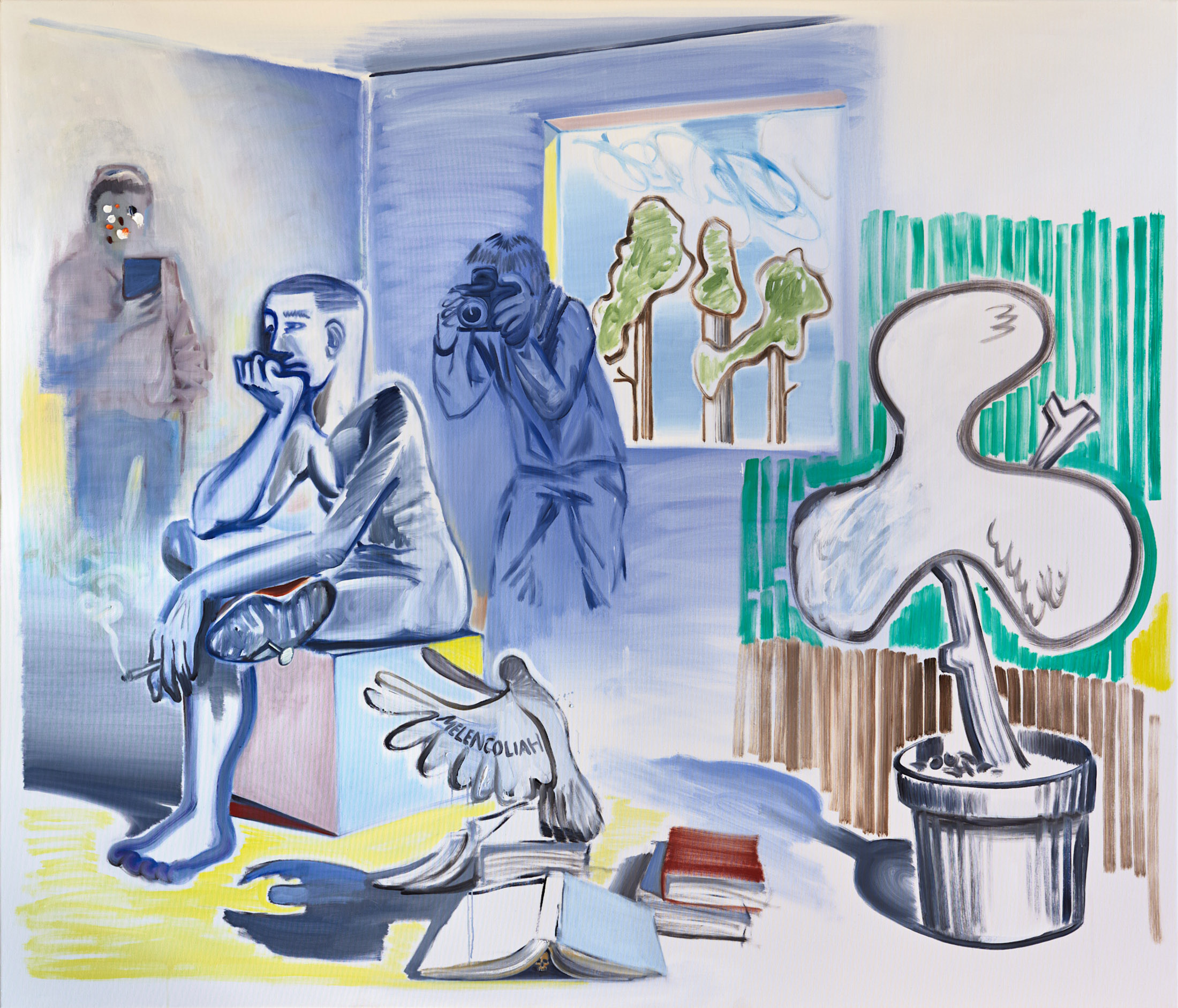

BF: You often collide opposites in your compositions, with the serious and the frivolous, the sublime and the banal, high and mass culture. The title of the publication expresses a similar contradiction: sensational nothing. Where did this title come from and what does “Sensational Nothing” mean in relation to your work?

GP: This diversity or disorder is characteristic of our time. The clash of opposites also started at university, at first it was only explicitly formal. For example: at the intersection of two lines drawn with a flat brush, a paralelogram is created. Later, I instinctively composed several of my paintings on this parallelepiped shape, discovering this shape in my paintings instead of the classic triangles, golden sections or squares. It started to interest me more seriously because I felt that it was at this intersection that opposing concepts could be juxtaposed and the most exciting things could be created. There is a tension in my work. That’s where a painting starts to become interesting for me, when things that are not obvious at first come together, are reinterpreted by each other and become unexpected. The “sensational nothing” is at such an intersection, where things are crammed together, but despite their turmoil from their interactions with each other, it is still a place of calm because of their beauty.

BF: In your paintings, different visual games and gags play a dominant role. What are the things and experiences that have shaped this particular sense of humour in your work? Do these appear in your work in direct or indirect ways?

PG: I think the immediacy of the banal is quite important. This layer of my paintings is probably the easiest to relate to, as they are familiar objects or characters to everyone. I try to offer the viewer an entry point not only in terms of composition but also in terms of content. For example, if someone in the picture is ironing, or a detail in the kitchen is transformed into a completely different situation, it can evoke memories and trigger associations in anyone. I like to build on these everyday experiences. I’m used to observing the audience’s reaction and I’ve noticed that humour is one of the first things that comes through to people, along with the visuals, is the point that most often draws them in. The visual humour is more of an inside, professional party.

When it comes to humour, I always mention Monty Python’s Flying Circus, which was a defining experience for me when it comes to that kind of thing. I’m also interested in the concept of the grotesque, for example, one of my paintings has a tiger with the words “Werbung” (advertisement) drawn in its stripes and was inspired by a short story by Bohumil Hrabal.

BF: Is it important for a painter to have a sense of humour?

PG: It’s probably an innate thing, it’s different for everyone, but I think it’s very important. If I had to define what a painter absolutely needs, one of them would be a sense of humour.

BF: In some of the drawings, you’ll notice strange phrases or words, like “everything ends up in rivers” or “Stay creamy”. Where do they come from? Is the phrase or the sketch first?

PG: It’s quite different in each case. When I come up with a text or a sentence, I don’t visualize it right away. It’s the same the other way round, I don’t have the title of every picture, I have a bad relationship with titling in general. Most of my paintings don’t have a title, or will have one later, or I have three. These sentences come from many places. Sometimes I read something while drawing and write it down. For example, “everything ends up in rivers” is one such case, because I was reading about environmental activists demanding that the Ganges be given human rights and this fragment of text comes from an article like that. And “stay creamy” just popped into my head while I was drawing this figure from some hand cream advertisement. I’m really interested in advertising, especially because of the simple language and the fact that it can be easily translated. In one of my drawings, inspired by Arvo Pärt’s My Heart’s in the Highlands, I drew a heart floating in a mountainous landscape, and combined it with an advert for a high-end luxury Jeep. This image, I think, sums up some of our problems nicely.

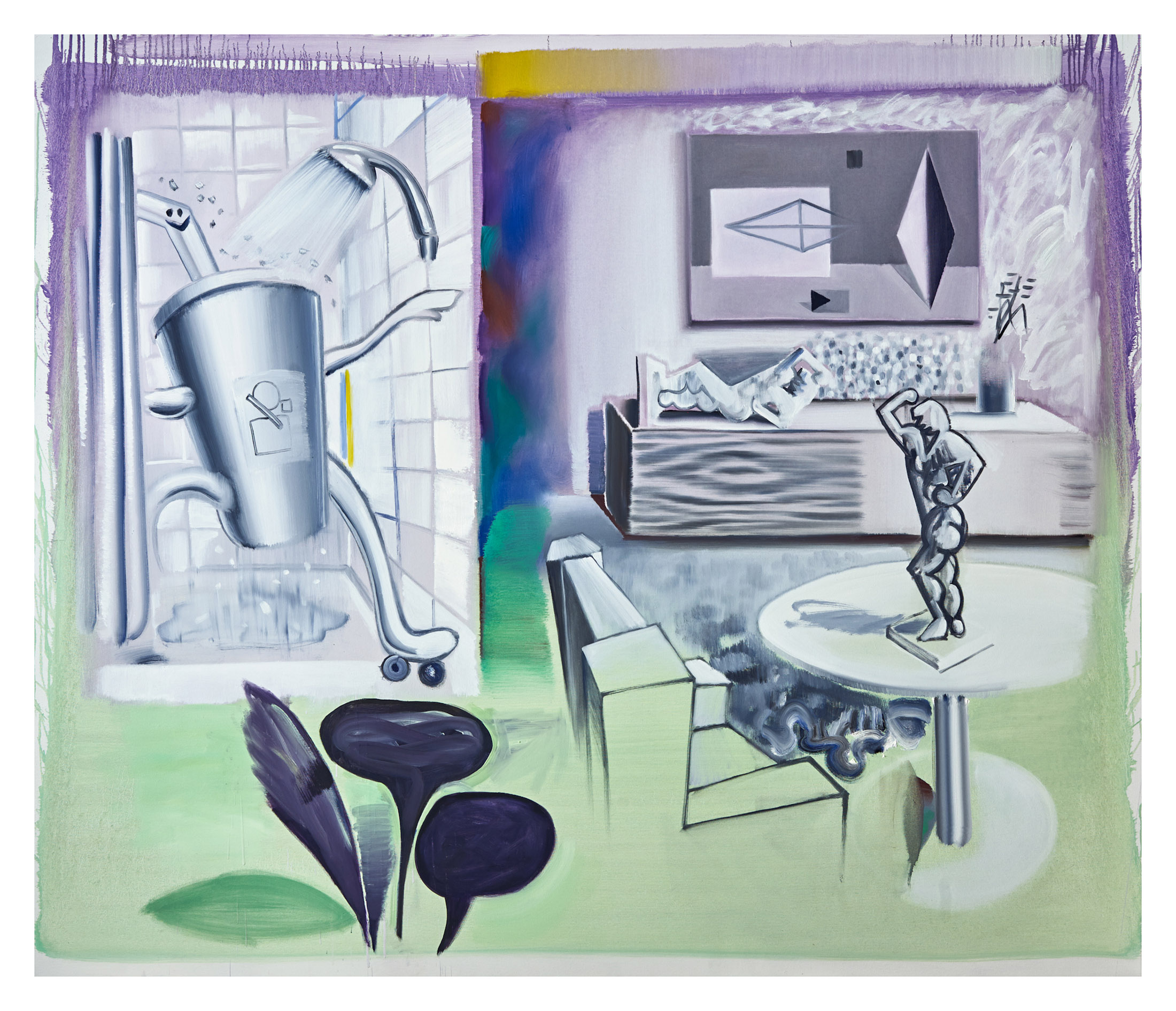

BF: Animated food and objects with cartoon-like legs and arms are also recurring characters in the book. Who are they?

PG: They are actually us. The soda cup is specifically someone rather than something, a character who enjoys life in its surreality, has everything, lives in a luxurious environment and has an Imre Bak painting hanging in his living room. There is also a certain social critique very subtly articulated in these characters, for example in the drawing where the fridge and the bin liners walk back to the mall. They are direct and can easily fulfil a comic or tragicomic role without becoming depressing.

BF: Are there any periods of art history that stand out in your mind that you draw a lot from these days?

PG: These days I’m most interested in the Baroque or Romanticism, I love these dense compositions, but it’s basically random what I touch on. I treat art as I would any other visual experience, I’m as much grounded in art history as I am in our other cultural heritage.

BF: Are there any artists, whether contemporary or historical, whose drawings you find particularly inspiring?

PG: I really like Hockney’s drawings… And recently I’ve been looking at more drawings and paintings by Francis Picabia.

BF: Which contemporary painter would you most like to exchange artwork with?

PG: I have a painting by Botond Keresztesi, we exchanged paintings last year or the year before. Otherwise I’m not particularly interested in having my own collection, I have enough objects as it is. But I’d like to see more of André Butzer, Rae Klein, Liu Xiaodong, Michael Borremans, Salman Toor’s paintings in person.