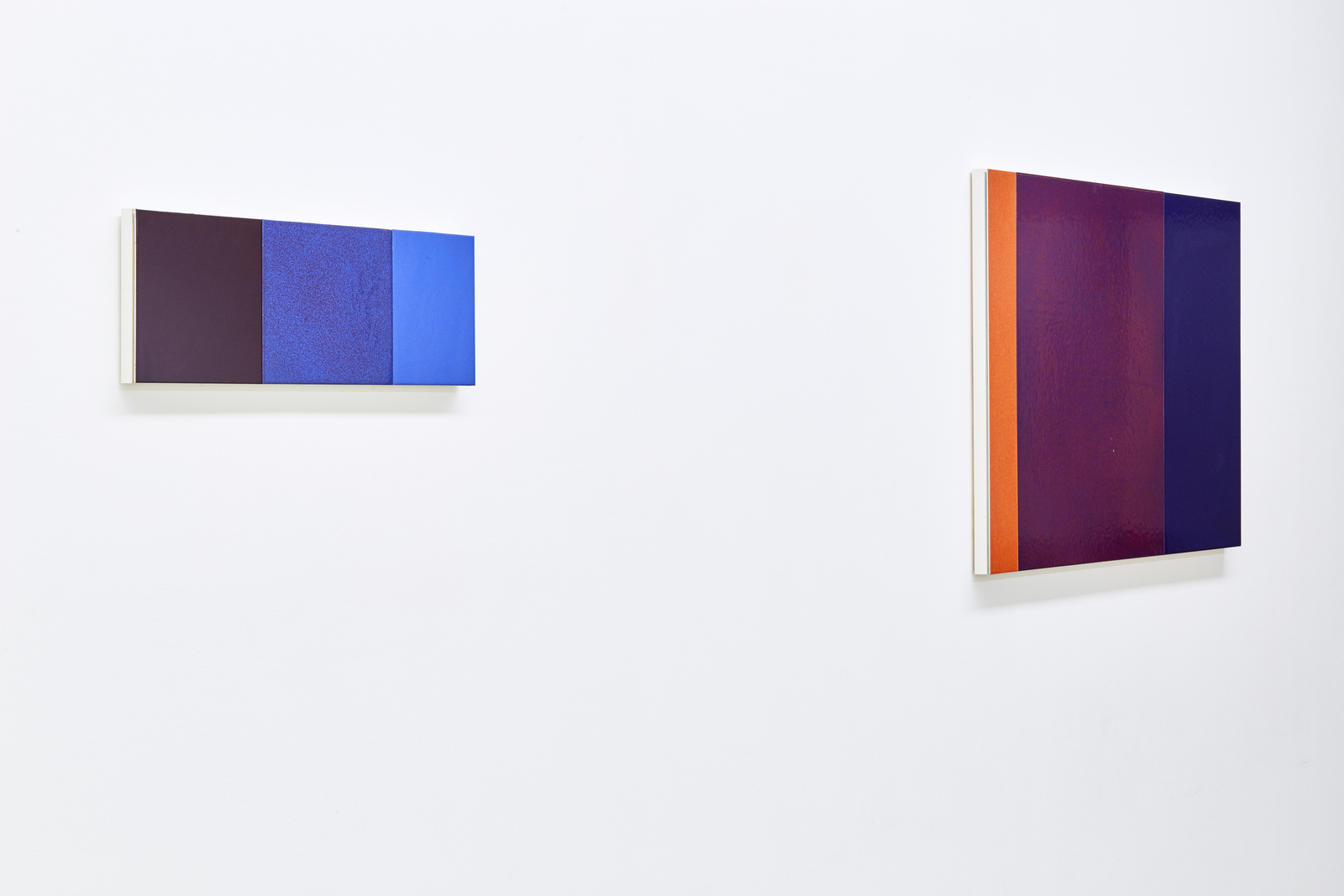

Artist: Gábor Kristóf

Exhibition title: Melting Point

Venue: Horizont Gallery, Budapest, Hungary

Date: November 23, 2016 – January 4, 2017

Photography: all images copyright and courtesy of the artist and Horizont Gallery

Polychrome monochromy

About the new works of Gábor Kristóf

In 2015, Gábor Kristóf stated he considers his works „images” much more so than „painting”.[1] Experimenting with different media, Kristóf often blurs the margins between painting and non-painting. He creates images that question the ways of using pictures[2] that thematize the endless circulation of virtual and objectified spectacles. All this leads towards the Benjaminian dilemma[3] of the original and its reproduction and opens an investigation into the raison d’etre of easel painting, filled with doubtful questions; the Duchampian questioning of „retinal” art guides towards challenges of the post-medium condition.[4]

One of Kristóf’s early series of works – representing press images of the Costa Concordia luxury cruiser accident– included paintings of the conventional sense (XLS. Extra-Long Shot, 2012). While investigating the relationship between catastrophe and spectacle and examining the flow of mediatized images, these earlier paintings were also reconsidering a tradition of the history of painting, arching from Caspar David Friedrich to Gerhard Richter. Kristóf recycled and enlarged press images into expressive paintings but the pieces of this series were not classic easel paintings as the artist – instead of using traditional support – painted onto the surface of offset press plates. Past the capsized boat’s dissolving contours and behind the sea of running patches of paint gleam the parts left empty on the metallic base. The reproduced images of the press are written onto the plates in unique and unrepeatable creations thematizing the relationship of painting and mass media. Sometimes, by summoning sights of overrun and spoiled images, Kristóf alludes to the random factor inherent in reproduction, to the incessant movement and change of images and their concept, to the shifts in the role of painting. Works of the Costa Concordia series reflect on tensions nesting between products of printing and painted works, among the real and hyperreal. They do so in a mode not foreign even to ethos of Pop Art and photorealism, quoting questions regarding theories of media and epistemology, referring to particular momentums of Michelangelo Antonioni’s renowned 1966 movie Blowup.

Kristóf is gradually receding from the traditional instruments of painting, and while the subsequent series is built on visual effects created by adhering residue on press plates, the works cannot be regarded paintings. Although fractions and small reminders of photographs, signage or adverts emerge on the discarded plates, yet the translucent overlapping of layers of old paint transform these ready-mades into effusive abstract paintings. Blurred visions, fragmented press images and other vestiges are rendered a particular meta-painting – as ready-mades they still retain their retinal characters. Accidental in structure, just like any abstract painting of spontaneous human gesture, these works were created by machines, bestowing on them serial quality. Kristóf attributes these by-products of mass-production to their maker, the Heidelberg printing press. Titled as Heidi, these abstract works – outstripping human imagery – are accessories of mechanized production. Even more precisely, the Heidis are objects lost and now found, though untouched they are not sterile. These works – with the spirit of post-conceptual painting’s „trans-aesthetics” – take account of questions generated by mediatized image-culture, mass-production and its (visual) refuse.

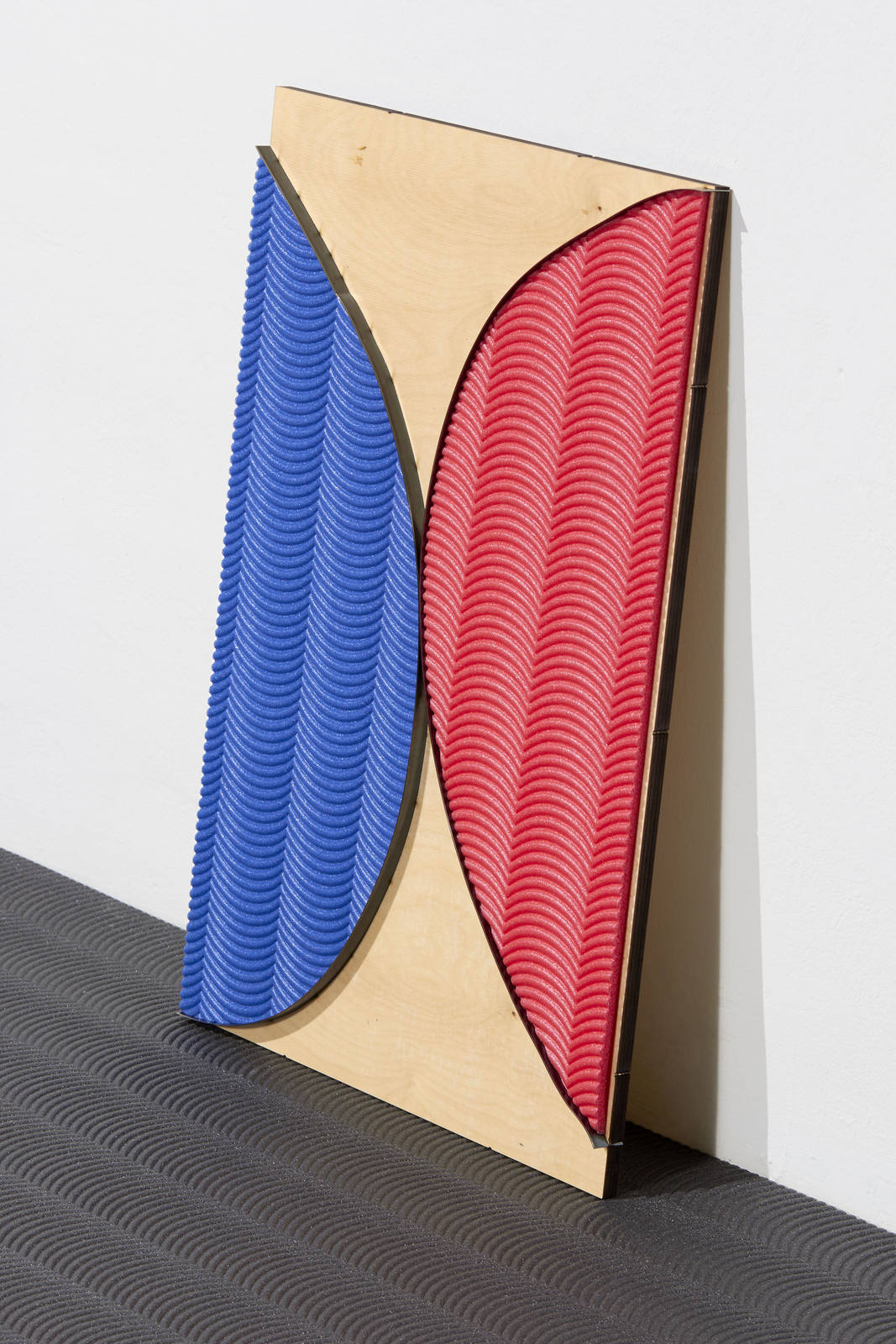

Kristóf closed the Heidi series with a distinct gesture: from a press plate, he cut out a ghost shaped piece and then confronted its negative with the positive. This unequivocal reference to the cut outs of Henri Matisse also hints at the spirit and mentality of modernism. The gesture of transposition – as though alluding to the affairs of presence and absence and of visible and invisible or the imaginary path of ever-mobile, incorporeal and ethereal images or the faith and transformation of modernist imagery into everyday design elements – creates a dense web of references from Matisse to Rauschenberg, arriving at significant artists of „painting after technology”.[5] Only after meticulous contemplation does the beholder notice that the contours of the Matissian ghost function as a sharp cutter, while the surface bears resemblance to an industrial die cutting tool. These tools are utilized to cut specific forms in industrial volumes and are an important part in the creation of cardboard boxes, labels or packaging. Kristóf created an ironically dysfunctional cutting tool, which, instead of an everyday object, draws and cuts the contour of Matisse’s torso motif as if it was an infinitely reproducible element of design. The edges of the blade follow the trembling motion of the artist’s hand. And while the elderly Matisse – avoiding excessive perfectionism – drew the contours of his shapes using charcoal attached to a stick, Kristóf creates the form on digital boards then manufactures die cuts from the computerised outline scribbles. In this respect, the Die Cut Drawings are based on manually designed, yet manufactured objects and forms, thematizing the affair between industrialized production and unique artwork.

Comparably to the case of the Heidi series, Kristóf utilizes found ready-made objects. He sprays “Brillo no more” onto a scrapped cutting tool, which graffiti item takes into account the consequences of the Warholian “transfiguration” of the commonplace.[6] While Warhol’s “factory” – reflecting ironically to the circumstances of the art-industry – perfected the mechanical reproduction of the unique work creating a particular “trans-aesthetics,”[7] Kristóf’s dysfunctional cutting tools eliminate the possibility of mass-production as they cease to be suitable for performing their original functions. Kristóf hangs the ready-found tool onto the wall, paints it over and declares it an easel painting of which’s contour is reminiscent of a reduced façade or the outlines of a factory building more so than the laid out sides of a cardboard box.

However, most of Kristóf’s Die Cut Drawings are not ready-mades, but unique pieces designed by the artist himself. In his newest works, Kristóf does not cite the shapes of Matisse, but creates spoiled line-drawings through the de(con)struction of geometrical forms. The computer-designed, manufactured cutting tool or quasi-easel paintings might be perceived as hard-edged, “hazardous” reliefs, occasionally enriched with polyfoam colour fields. The works appear as paintings bereft of paint, as structures or variations that rhyme with each other suggesting industrial aesthetics yet remaining unfit for mechanized production. If one prefers, the juxtaposed tools may be read as stanzas. They evoke and prohibit industrial production and as such take stock of the notion of the “cutting edge”.

At the same time, the Die Cut Drawings are painting tools, allowing the creation of collages and de-collages. They are images and their negatives at once. The die cut tools are capable of the deconstruction and reproduction of the evoked schemes and forms. As such, they investigate the connections of industrial technology and contemporary art.

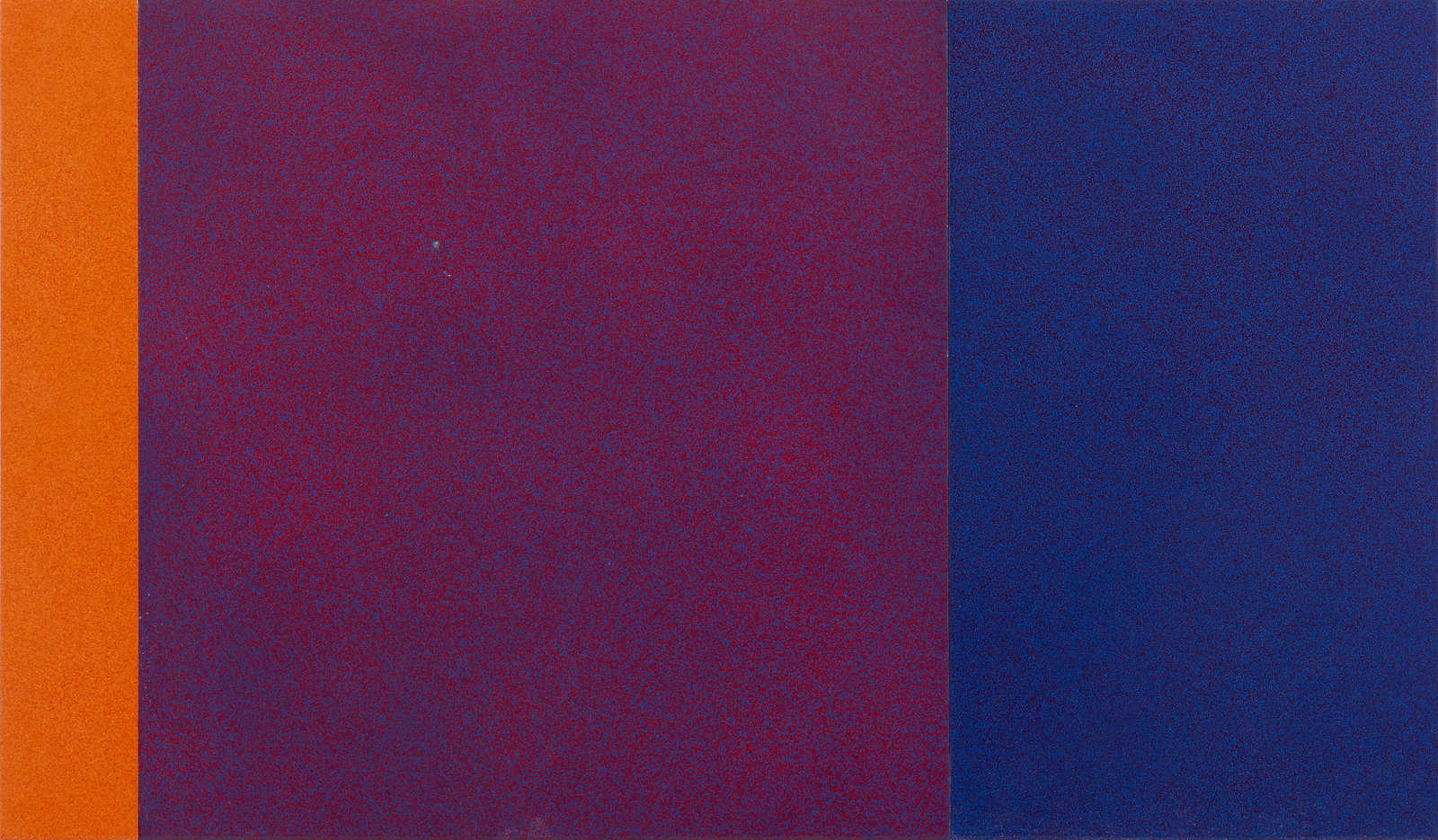

Though the support of the Die Cut Drawings – in accordance with the structure of cutting tools – are wooden boards, still Kristóf did not move away from the offset media. In another series – created in parallel with the Die Cut Drawings – he experiments with the sintering of metal plates. While the process of sintering originally means the monochrome surface treatment of metal objects, Kristóf, applying a special technique, creates polychrome, grainy surfaces by which he eliminates the homogeneity of sleek industrial coloration.

From a distance, the pigment particles melting atop the surface appear as a unified colour field. However, a closer look allows the vision of a uniquely vibrating spot-structure. This evokes the illusionistic quality of painted marble surfaces of the Renaissance – such as “splattered” detail of a fresco by Fra Angelico, interpreted by Georges Didi-Huberman[8] as a uniquely self-reflexive pictorial item. Concurrently, the painterly microstructures demonstrate the phenomena of optical colour mixing leading from pointillist methods to press screens and the scenery of digital image noise, all the while rethinking recurring motifs of painting and theoretical implications of digital imagery.[9]

The “splattering-effects” suggest spontaneity, however the burned surfaces feel foreign. To an extent, the works summon the poured surfaces of abstract expressionist canvases, but as compositions they allude to geometrical abstraction and classic examples of colour field painting. Kristóf arranges the pictures into triptych-like colour sequences – the resulting vertical bands are redolent of Barnett Newman’s „zips” and sublime picture fields. However, these are not painted surfaces. As afterimage or remote allusion, they invoke substantial painterly motifs. Alluding monochromy, polychrome colour bands remind of stripes of colour at the edge of proof prints. Also evocative of tiles, not only do these works cite items of everyday design but the virtual „tiles” of Windows. On the glittering surface, interfering pigment spots sublimate into raster-dots or might be apprehended as digital image noise.

Kristóf applies a unique technique in creating his works. The process hints at the methods of László Moholy-Nagy when ordered his Telephone Pictures (1922) from enamel factories. Although in the case of Kristóf, the sterile industrial visuality is absent, as the artist’s manual interventions (the changing, mixing and dispersion of grain size in powder paint) eventuates these works’ significant contingency.

The surfaces are defined through the dialectics of polychrome and monochrome. Kristóf consciously cites Aleksandr Rodchenko’s triptych Pure Red Colour, Pure Yellow Colour, Pure Blue Colour (1921), the dark surfaces of Ad Reinhardt’s oeuvre, Blinky Palermo’s “Fabric paintings” built of textiles and Gerhard Richter’s monochrome works.[10] These references show Kristóf, through his own Polychrome series, commenting on the lengthy artistic discussion of the end of painting. His chosen inspirations were, in the respective times of their creation, intended also to be the “last painting”.[11] Kristóf cited examples of geometric abstraction and monochrome painting as peculiar phases of grief, in a sense how, in one of his studies, Yve-Alain Bois implied modernist painting was indeed work of mourning.[12]

The Polychromes of Gábor Kristóf are not paintings, but rather pictures of painting and its current condition. On small-scale metal plates, the artist creates an alternative RAL scale, some of which’s fields are exactly the size of a credit card. Kristóf utilizes maximally this analogy on his flow chart-like series: he juxtaposes the ever-diminishing circular shapes of the MasterCard logo on the sintered, grey surfaces of “cards”, giving a playfully cosmic character to the dynamics of market processes (Losing Credit, 2016). All this might be an allusion to the ambivalent relationship of art and market, or may investigate the waning of intensity in face of image-inflation, mass-production in the age of (digital) technology in which vanishes and reproduces the Benjaminian notion of aura.[13]

Though the parallel series (Die Cut Drawings and Polychromes) of Gábor Kristóf are not paintings, they do thematize and deconstruct core elements of painting. Colour (colore) and line (disegno) – Rodchenko evoked these complementary items of painting, dissecting and “exceeding” the very elements of his craft. Kristóf does not take the sides in the dispute of “colour” and “line”, he rather juxtaposes and de(con)structs both. He places them on the shorelines of visual arts in the era when painting is placed “beside itself”.[14] In this situation – both literally and figuratively – does Gábor Kristóf investigate the hard edges and plastic borders, and theoretic systems, melting points of painting. He sheds light on the true polychrome character of the monochrome mass of image-flow and its inherent intellectual and pictorial potential.

–Dávid Fehér

[1] Büro imaginarie (Emese Mucsi – Judit Szalipszki): „Megvannak a határok, de már nem kell őket felügyelni” (A converstaion with Gábor Kristóf), in: Kristóf Gábor. Offsetting¸ Horizont Galéria, Budapest, 2015, 27.

[2] The notion of „pictures” eliminating the borders betwwen different media refers best to Douglas Crimp’s famous exhibition Pictures (Pictures, Artists Space, New York, 1977), or the generation named after it, as well as Crimp’s later essay (Douglas Crimp: Pictures, October, Vol. 8., Spring 1979, 75–88.).

[3] Walter Benjamin: The work of art in the age of mechanical reproduction, 1963, published in: Illuminations, Schocken Books, New York, 2007. 217 – 251.

[4] Rosalind Krauss: A Voyage on the North Sea: Art in the Age of the Post-Medium Condition, Thames and Hudson, New York, 1999

[5] Consult Painting After Technology, a sub-unit of the Tate’s 2015 exhibiton Making Traces, with the inclusion of artists as Sigmar Polke, Albert Oehlen, Tomma Abts, Christopher Wool, Amy Sillman, Charline von Heyl, Laura Owens, Jacqueline Humphries (curator: Mark Godfrey)

[6] Arthur C. Danto: The transfirguration of the commonplace, Harvard University Press, 1983

[7] Consult Warhol’s statement „I want to be a machine” and its „trans-aesthetical” implications. Jean Baudrillard: Simulation and Transaesthetics. Towards the Vanishing Point of Art, in: Sylvere Lotringer (ed.): Jean Baudrillard. The Conspiracy of Art: Manifestos, Interviews, Essays. Semiotext(e)–MIT Press, New York, 2005, 98–110.

[8]Geroges Didi-Huberman: Fra Angelico. Dissemblance and Figuration, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1995, 2.

[9] Donald Kuspit: The Matrix of Sensations, artnet.com, 2005, elérhető:

http://www.artnet.com/magazineus/features/kuspit/kuspit8-5-05.asp (Last accessed 13 November, 2016)

[10] Benjamin Buchloh: Gerhard Richter. Acht Grau, kat. Deutsche Guggenheim, Hatje Cantz, Berlin, 2002

[11] In connection with the discourse on the end of painting consult: The Mourning After: A Roundtable. Keynote by Arthur C. Danto. David Joselit, moderator, Yve-Alain Bois, Thierry de Duve, Isabelle Graw, David Reed, Elisabeth Sussman, Artforum, Vol. 41., No. 7., March 2003, 206–211., 267–270.

[12] Yve-Alain Bois: Painting: The Task of Mourning, in: David Joselit – Elisabeth Sussman – Bob Riley (eds.): Endgame. Reference and Simulation in Recent Painting and Sculpture, kat. The Institue of Contemporary Art, Boston, The MIT Press, Cambridge (Mass.) – London, 1986, 29–49.

[13] Boris Groys: Modernity and Contemporaneity: Mechanical vs. Digital Reproduction, in: Boris Groys: In the Flow, Verso, London – New York, 2016, 137–146.

[14] David Joselit: Painting Beside Itself, October, Vol. 130, Fall 2009, 125–134.