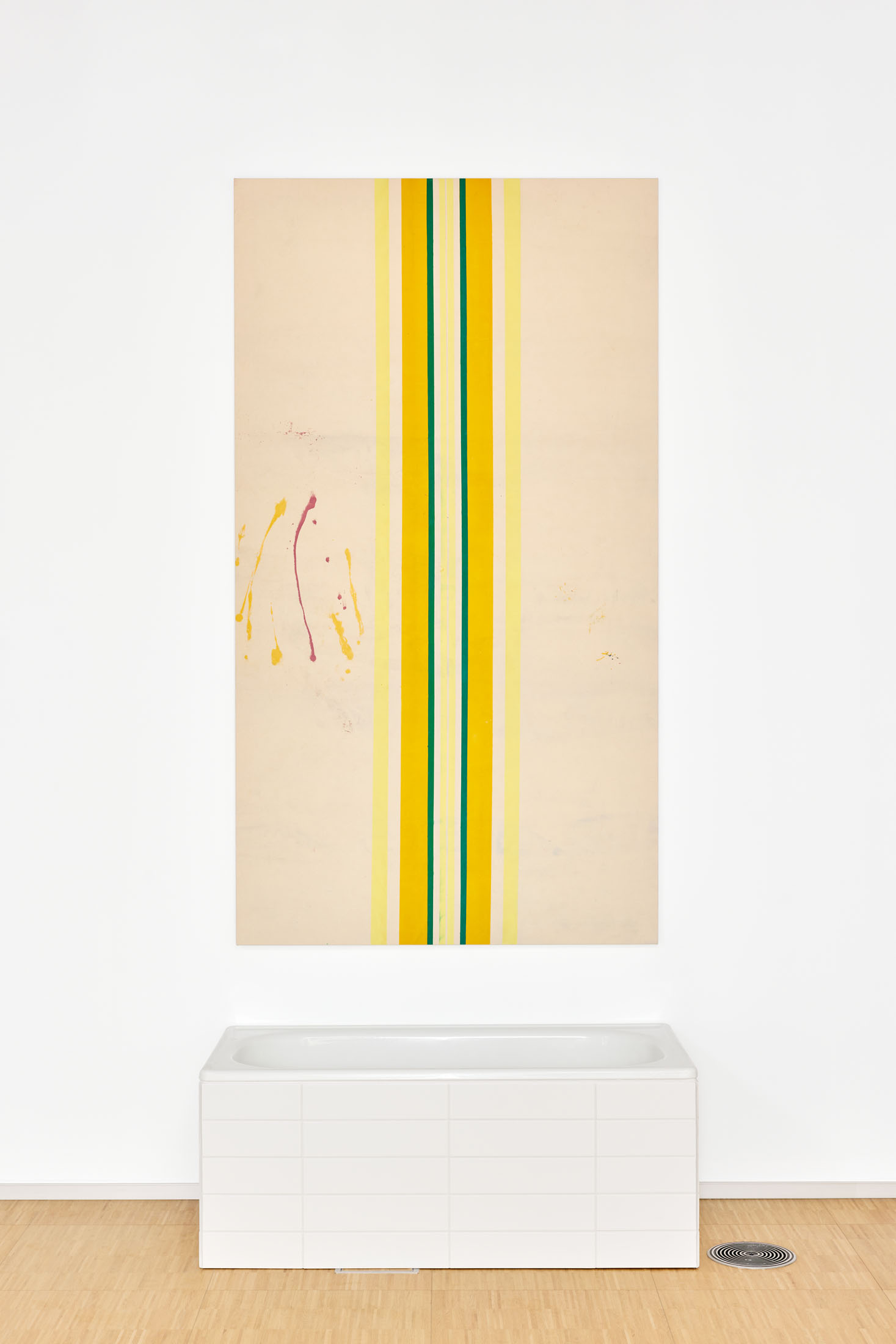

If at any point a ranking were to be made of the most absurd coincidences in recent art history, we would find close to the top the fact that the grotesque corner bathtub in Fredrik Værslev’s exhibition at Stormen kunst/dájdda in Bodø looks as if it had been custom-built, almost to the millimeter, for the corner in which it has been installed. The fact that something so ugly can even end up being installed so elegantly is an achievement, an ironic stroke of accidental genius. Værslev’s idea for placing objet trouvé bathtubs spread out in the exhibition space, and hanging the paintings in relation to them, originally came from a photograph of one of the American artist Christopher Wool’s Riot paintings, installed above a swimming pool in what seemed to be a gem of a modernist villa. Wool’s display is a conceptual demonstration of how art’s “rebellion” collides, often in a surreal way, with how collectors “domesticate” work by incorporating it into the interior design of a home. The Wool above the pool achieves this more spectacularly than what we’re used to seeing.

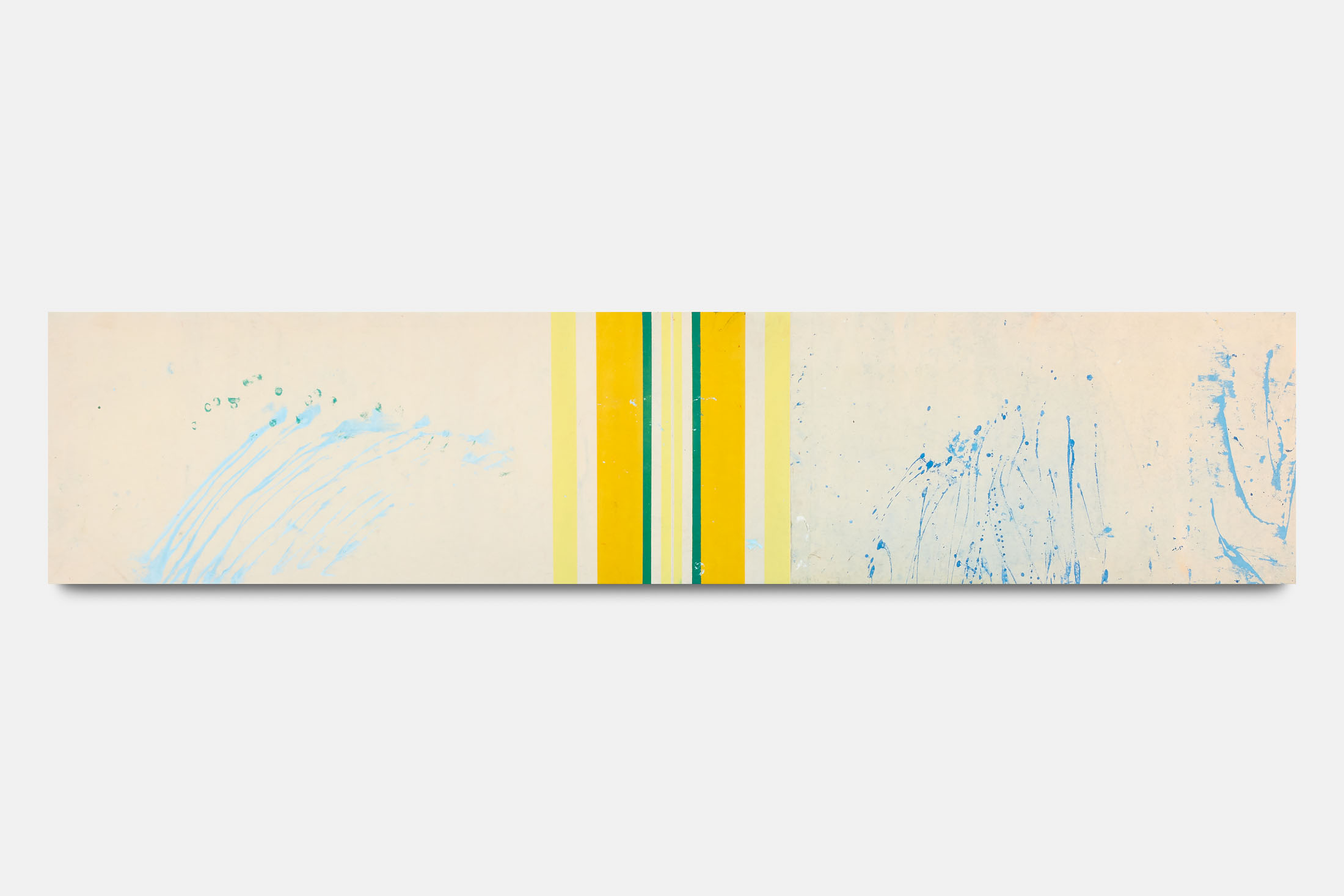

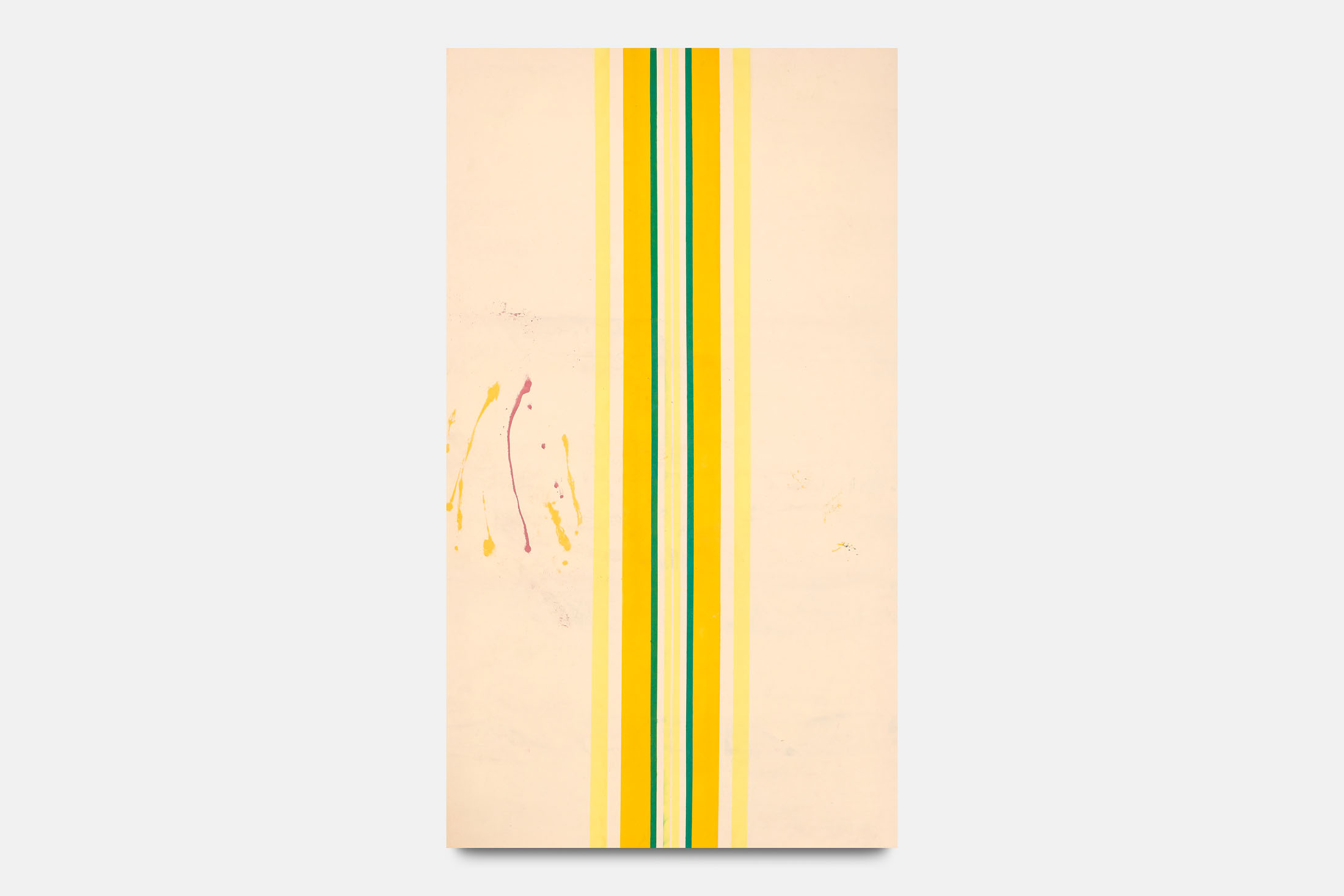

Fredrik Værslev has, through nearly 20 years of artistic practice, worked with a form of painting where he combines two kinds of inheritance: the legacy of abstract painting in the US and Europe from the 1940s to today, and the legacy of the Norwegian middle class’s aesthetic preferences and exercise of taste. In earlier series of works, he has referred to patios, privacy fences, venetian blinds, floors, and the sailboats he could see from his childhood town of Drøbak on the east side of the Oslo Fjord, and later curtains.

In this newest series, it is primarily a matter of using and combining expressions from various directions and practitioners within second-generation Abstract Expressionism. This predominantly American painting tradition dominated much of art history in the postwar period. Such painting characterized the works of a wide range of artists, from figures as different as Sam Francis and Joan Mitchell to Jakob Weidemann. Eventually, in the 2010s, it was linked to so-called Zombie Formalism, where a group of younger artists, including Værslev, were accused of producing a kind of “undead abstraction”—nonfigurative painting not only on autopilot but as literal walking corpses in the graveyard of art history.

This scathing criticism can be said to have rolled off Værslev, and in these latest works one could say he deliberately probes and studiously mocks exactly how zombified a painting can get. The paintings contain concrete gestures, brushstrokes, and abstract patterns that point directly to various figures within postwar abstract painting, but also to specific passages in a painting by Edvard Munch. What ties them together is that they are executed in a way that can simultaneously pass as “good abstract painting” and yet are undeniably rather ugly. And it is precisely this adjective that perhaps occurs most frequently in my conversations with the artist. This began with an exhibition we made together at a museum where I previously worked, where the floors in the galleries I had invited Værslev to exhibit his series Garden Paintings were undeniably extremely ugly. The solution was to lay down 250 square meters of decking and then paint it in four different colors taken from those used on seaside cabins along the Oslo Fjord. This move joined the history of institution-critical art’s architectural interventions that alter the properties of an exhibition space and prod at the white cube’s status as a “sacred” art space. The decking built in the museum, however, was also undeniably quite ugly, but it was ugly in a different way, a way that also looked fantastic because conceptually it was as tight as it could be.

Fredrik Værslev has always been concerned with precision in his exhibitions, and these often function almost as installations and architectural constructions where the works can either be seamlessly integrated or, on the other hand, contrasted with something that appears completely out of place and aesthetically inappropriate. The latter was the case at the artist’s exhibition at Frac Bretagne, in the French city of Rennes, in 2022, when Værslev placed in front of the works in the exhibition—pieces from several of his most recognized series—a larger number of cheap white plastic garden chairs. The chairs, however, had a certain kinship with the materiality of the new series of terrazzo paintings Værslev showed in that exhibition, based on a new canvas with a surface reminiscent of white plastic, which for the most part looked very “cheap.” That the artworks are installed in contrast to their surroundings is equally the case at Stormen kunst/dájdda in Bodø. The exhibition’s bathtubs, which obviously also provided its slapstick-inspired title Badekaran1, were moreover paired with the utterly arbitrary painting of Edvard Munch’s Bathing Men that adorns the exhibition’s poster.

The corner bathtub, which thus found its place—its absurdly precise position—in a corner it seemed to have been custom-built for, thereby takes on a role as one of the most peculiar exhibition design gestures in recent times. The relationship between this chlamydia cauldron of institutional critique and the corresponding parodic maneuvers on the exhibition’s canvases creates a character of both contrast and harmony, ugly and beautiful, high and low, and not least, wet and dry.

–Erlend Hammer