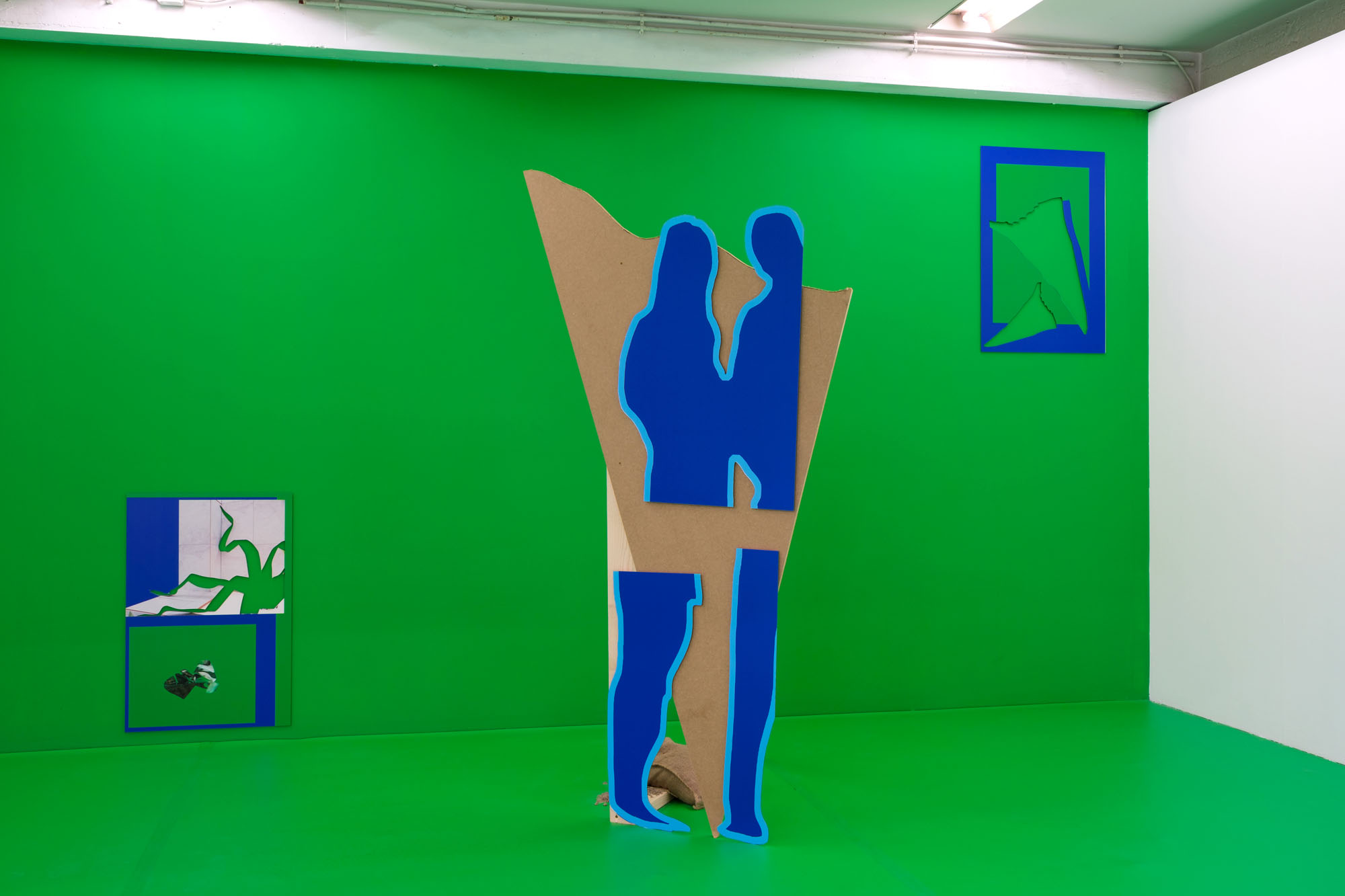

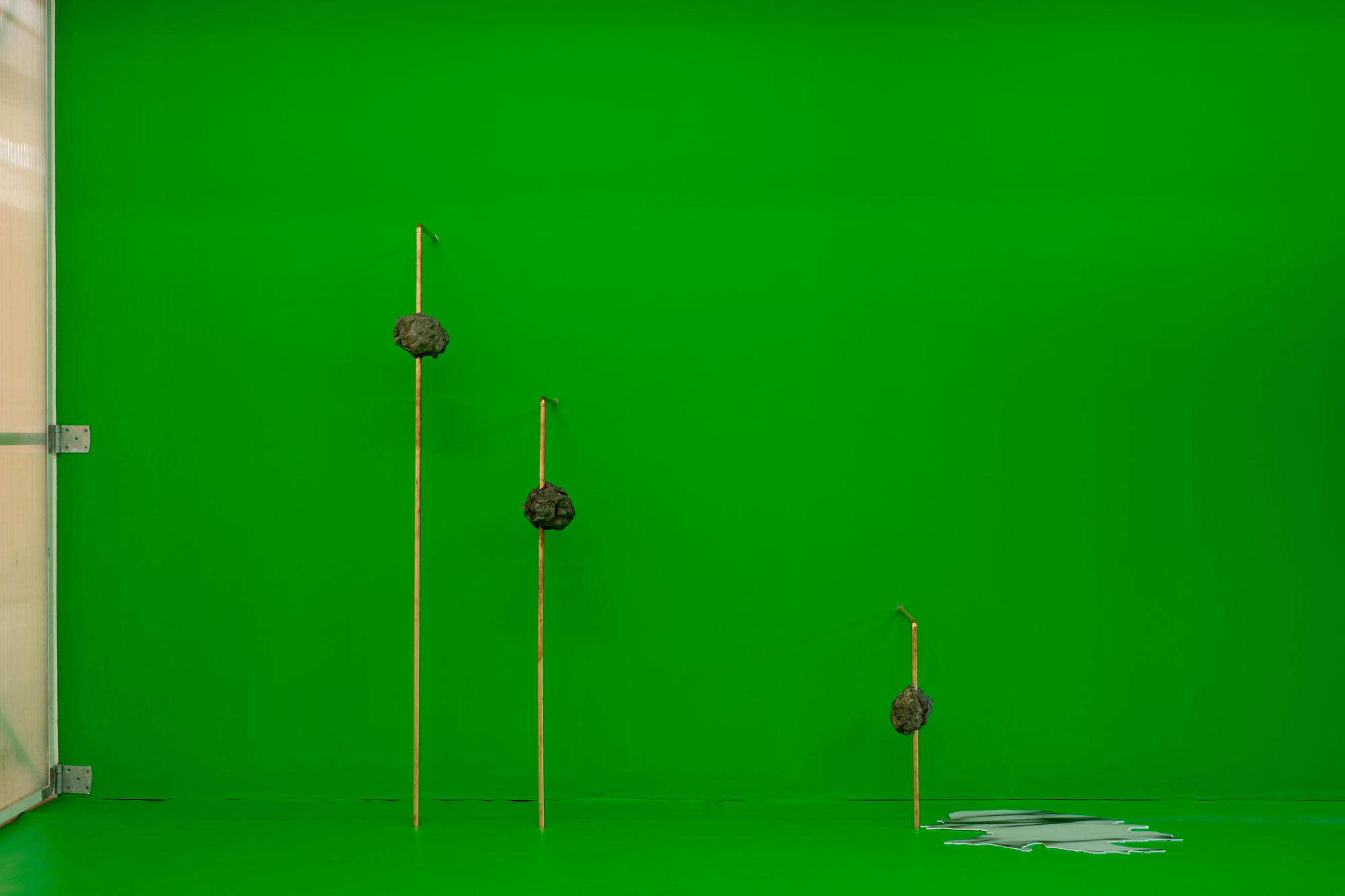

Artist: Felicity Hammond

Exhibition title: Remains in Development

Curated by: Eline Verstegen

Venue: Kunsthal Extra City, Antwerp, Belgium

Date: January 25 – March 1, 2020

Note: Exhibition booklet is available here

Photography: © We Document Art, images courtesy of the artist and Kunsthal Extra City

For her first exhibition in Belgium, Felicity Hammond brings together different bodies of existing work in a new installation. The three groups of works in ‘Remains in Development’ comprise a number of large-scale photo collages, sculptural elements and a chroma key installation. These projects were previously brought together in Hammond’s 2019 publication ‘Property’. The pages from the book have been translated, as it were, into three-dimensional space. Surprising new meanings have been lent to the individual works through their recombination. In this way Hammond’s practice remains in constant development, as hinted at by the exhibition’s title. With ‘Remains in Development’, Hammond also alludes to the limitless processes of urban development, by which remains are both built on and, eventually, left behind.

In her work, Hammond focuses not only on the physical appearance of buildings, but also on their social impact: for whom are they intended and whom do they force out? Whether it concerns new residential homes or commercial properties, so-called “regeneration” is usually a euphemism for strictly entrepreneurial investment rather than any actual improvement for the local area and its inhabitants.

Hammond’s work shows us that these future properties are often bought and sold based solely on illustrations of architectural proposals. Computer-generated and manipulated representations of the development projects are shown off in a variety of formats: in brochures, on websites and on large billboards or banners concealing the construction sites themselves. Rather than merely presenting an image, these representations tell a story of the lifestyle that the site stands to make reality.

These representations influence the image of what ‘the city’ is and how it is viewed across the globe. This limited imagining of the built environment is increasingly coming to be one that is universally shared. Every apartment block, every business park, every city is starting to look more and more the same. These sterile visions of the urban space of the future are leading to virulent homogenisation.

Hammond intentionally plays with the methodologies that are at the foundation of these architectural projections. She undermines their visual language, extracts details from their context, and bursts the bubble of the illusions that these digital renders invariably conjure. She takes photos of them herself, which are in turn distorted and warped into large still-life-like photo collages. Indeed, she describes photography as a material that straddles the digital and the physical world. Not only does she present alternative interpretations of the urban environment, at odds with the false promises usually perpetuated, she also welcomes a renewed clash of the virtual with the material.

While the work of Felicity Hammond may at first sight appear rooted in the aesthetic, one finds that it is neither an easy nor necessarily a pleasant experience to wander her archaeological site of the future.