Artists: Talia Chetrit, Moyra Davey, Barbara Kasten, Kate Newby

Exhibition title: Every Day I Make My Way

Venue: Minerva, Sydney, Australia

Date: April 29 – June 11, 2016

Photography: all images copyright and courtesy of the artist and Minerva, Sydney

“Notes On Photography & Accident”*

Moyra Davey

For a long time I’ve had a document on my desktop called “Photography & Accident.” It contains passages from Walter Benjamin’s “Short History of Photography,” Susan Sontag’s On Photography, and Janet Malcolm’s Diana & Nikon. All of the quotes hover around the idea that accident is the lifeblood of photography.

Walter Benjamin: “The viewer [of the photograph] feels an irresistible compulsion to seek the tiny spark of accident, the here and now.”

Susan Sontag: “Most photographers have always had an almost superstitious confidence in the lucky accident.”

Janet Malcolm: “All the canonical works of photography retain some trace of the medium’s underlying, life-giving, accident-proneness.”

Add to these exceptional writers on photography Roland Barthes and his notion of the punctum: that “cast of the dice . . . that accident which pricks” (Camera Lucida).Benjamin’s masterpiece is from 1931, Sontag and Malcolm were publishing their superlative prose in the mid-’70s in the New York Review of Books and theNew Yorker respectively, Barthes’ Camera Lucida appeared in 1980. I have long been drawn to these writers, and I am fascinated by the ways their thinking overlaps. Some instances are well known, as in the homage paid by Sontag to Benjamin and Barthes, but other connections are more buried: Sontag’s references to the photograph as “memento mori” and “inventory of mortality” before Camera Lucida; Sontag and Malcolm circling around the same material in the ’70s (accident, surrealism, the vitality of the snapshot versus formalism) and coming to remarkably similar conclusions about “the enigma of photography.”

The notion of accident has had many meanings, from “decisive moment” to “photographing to see what something will look like photographed.” But is this an anachronism for contemporary work, decades after the ethos of the street?

Roberta Smith, writing in the New York Times, has aptly characterized recent trends in image making (very large, staged color photographs) as “the Pre-Raphaelite painting of our day.” The problem, to state it baldly, is one of stilt coupled with bloat. Absent from these oversized tableaux is the inherently surrealist, contingent, “found” quality of the vernacular photograph, the quality my quartet of writers so eloquently identifies and holds so dear. My goal is to reclaim this critical history of ideas in relation to contemporary photographs, and to understand how the notion of accident might still be relevant.

Being

July 2006. In the hospital, on steroids, I have the feeling for perhaps the first time in my life that I can simply “be.” I no longer have to push myself to do anything, to prove anything. I can just sit on the bed and be.

Writers…

I read Benjamin over and over, sometimes getting it, sometimes not. I identify mostly with his nostalgia, which seemed to ebb and flow, depending on which part of his temperament prevailed. At times it was the Marxist side that dominated, when he was under the sway of Brecht and spoke of mechanical reproduction as a liberation from aura. But Benjamin was also, as Sontag points out, a melancholic collector who sought out beauty and authenticity, and who wrote lovingly of the earliest auratic photographs, the long, drawn out exposures that preceded the mass hucksterism and popularization of the medium.

I confess to never having had a handle on Sontag’s On Photography. It’s teeming with insight, and contains exhilarating passages but I’ve always had trouble keeping the essays straight in my mind. William Gass, reviewing the book in the NYT when it came out in 1977, sheds some light on her method: “Sontag’s ideas are grouped more nearly like a gang of keys upon a ring than a run of onions on a string.” A perfect description of On Photography’s epigrammatic structure, where ideas, indented with dingbats, accumulate, and indeed follow one another with a sort of loose, fragmentary randomness. I never connected on an emotional level with Sontag; nonetheless I’m awed by her avant-gardism and erudition. Sontag’s book prefigured Barthes’. Sontag and Barthes were friends, and I wonder how much On Photography, especially its ideas about death and the photograph as memento mori, might have been generative to his thinking in Camera Lucida.

Notes

Roland Barthes spoke of his love of, his addiction almost, to note-taking. He had a system of notebooks and note cards, and Latinate names to designate different stages of note-taking: notula was the single word or two quickly recorded in a slim notebook; nota, the later and fuller transcription of this thought onto an index card. When away from his desk he used spring-activated ballpoint pens that required no fumbling with a cap, and wore jackets with pockets that would accommodate these tools. He maintained friends who would not question his habit of stopping, mid- walk, mid-sentence, to quickly note a thought.

Barthes: “When a certain amount of time’s gone by without any note-taking, without my having taken out my notebook, I notice a certain feeling of frustration and aridity. And so each time I get back to note-taking (notatio) it’s like a drug, a refuge, a security. I’d say that the activity of notatio is like a mothering. I return to notatio as to a mother who protects me. Note-taking gives me a form of security” (La Preparation du Roman, 1979).

Reading and thinking about note-taking gives me a form of security, a thrill even…

Hannah Arendt on Benjamin: “Nothing was more characteristic of him in the thirties than the little notebooks with black covers which he always carried with him and in which he tirelessly entered in the form of quotations what daily living and reading netted him in the way of ‘pearls’ and ‘coral.’”

Diaries

A Barthes Reader, edited by Sontag, begins and ends with essays on the diary. “Deliberation,” published the year before Barthes died, is a melancholic meditation on his ambivalence over that form. He finds pleasure in the spontaneity of recording an entry, but ultimately expresses irritation with the “verbless sentences” and the “pose” of the diary voice. He feels that everything he writes is merely reproducing the voice of all the diaries that have come before.

Vision

I’m working haltingly on this essay while simultaneously undergoing treatment for optic neuritis in my left eye. My doctors are kind people who especially want to help me because I am a photographer; my ophthalmologist collects Leicas and is always eager to discuss optics and lenses and uses the terminology of f-stops and “shutting down” to describe the darkened perceptions of my affected eye. I don’t tell my doctors that my production of photographs has dwindled to a trickle, that I’ve grown melancholic and ambivalent about photography. After all, one of the motivations for this essay has been to try to rekindle a desire to make images.

I have a resistance to engaging my true topic, “photography & accident,” and instead find myself inexorably drawn to thinking about writing. As I struggle to write about photography, I remember how much easier it seemed to write about reading and writing, and how much I love to read about both these subjects. I begin to wonder if it’s not just the modernist paradigm kicking in, that a metadiscourse is always more satisfying: painting about painting, photographs about photography, and writing about writing. I can always be engaged by discipline- or medium-specific metaproductions.

Words, Pictures

Sontag: “A photograph could also be described as a quotation, making a book of photographs like a book of quotations.” And Barthes speculated that the haiku and the photograph have the same noeme, the same essence. What each reveals, unequivocally, is the “that has been.”

Light Writing

This is the Greek origin of the word “photography,” and Eduardo Cadava reminds us that Henry Fox Talbot, author of The Pencil of Nature, used the expression “words of light” to describe his first photographs. In Camera Lucida Barthes gives us a possible Latin equivalent for “photograph”: “imago lucis opera expressa,” an image “expressed (like the juice of a lemon) by the action of light.”

Fragments

I’m drawn to fragmentary forms, to lists, diaries, notebooks, and letters. Even just reading the word “diary” elicits a frisson, a touch of promise. It’s the concreteness of these forms, the clarity of their address, that appeals and brings to mind Virginia Woolf’s dictum about writing, that “to know whom to write for is to know how to write.” I am similarly drawn to fragments of an artist’s oeuvre, a single image in a magazine or brochure. I tear these out and hold onto them. No doubt I also like the miniaturization, and the possibility of possessing the thing.

Taped to the wall above my desk is a Thomas Hirshhorn print of Emma Kunz’s geometric shapes, stolen for me from his last show by my friend, filmmaker Jennifer Montgomery, and beside it is a page torn out of Afterimage, with a Gabriel Orozco photo (Coins in Window) reproduced in black and white.

In a pencil jar is a six-inch nail, also pinched from the Hirshhorn show by Jennifer, and embedded between it and the pens and pencils is a tiny reproduction of an Andrea Gohl window, an image I saw in an Allen Frame show at Art in General a few years ago. Frame is an artist I discovered in Nan Goldin’s curated show Witnesses:Against Our Vanishing in 1989 at Artists Space, a show that included many other loved artists, such as David Wojnarowicz and Peter Hujar. Frame made color diptychs of Kodachrome snapshots with handwritten captions in the margins. They seemed to be images of friends and lovers, and reminded me of Larry Clark’s Tulsa.

All of these images, the ones at hand and the ones remembered, become part of a psychic landscape; they feed a fantasy, have what Sontag calls a “talismanic” quality.

Benjamin and Barthes

Sit at glass-topped table. Copy passages from Benjamin, Barthes. Begin to see new connections.

Sontag and Accident

I am struck more than ever by Sontag’s prescience.

She mentions accident more than once, including this passage on photography’s privileged relation to surrealism: “Surrealism lies at the heart of the photographic enterprise . . . has always courted accidents, welcomed the uninvited. . . . What could be more surreal than an object which virtually produces itself, and with a minimum of effort?” (I wonder what debt Rosalyn Krauss’s essay on the surrealists and photography might owe to Sontag, and go back to Krauss and look over her footnotes. No mention of Sontag.)

For Sontag it is the unmanipulated photograph that is inherently surreal and comes about “through a loose co-operation (quasi-magical, quasi-accidental) between photographer and subject.” It does not require elaborate means or technical ingenuity; in fact the opposite is true: it is artifice that kills off what’s interesting and vital in a photograph. Artiness squelches: “The less doctored, the less patently crafted, the more naïve, the better a photograph is likely to be.”

October 10

First Interferon injection. Pictures of dust motes in sunlight after shaking out bedspread; picture of large weed growing by the West Side Highway. I’ve broken the ice, am taking pictures again. I risk something, but what, exactly? I am overcoming my resistance to committing further images to the world, new negatives to the archive. Think again of Nina’s long howl as she took the plunge.

October 13

For Sontag and Malcolm accident is the vitality of the snapshot, to which they oppose the turgidity and pretentiousness of art. For Barthes accident is wholly subjective; it is what interpolates him into any given photograph.

It’s becoming clear to me that my own relation to accident is also extremely subjective, that accident is to be located outside the frame somehow, in the way we apprehend images. I shun the formal encounter via the institutions of galleries and museums, and gravitate to books and journals.

October 15

Read. Read something else. Go back to the first thing and see how it is changed.

October 25

Increase Interferon. Dream-filled, restless sleep. Prompted by Sontag’s diary, read Rilke, who said: “Love the questions.”

October 28

Insane mood swings.

Bed

Early spring, 2007. Think back to July, sudden blindness in left eye and diagnosis of multiple sclerosis (a disease of accidents, “mistakes of the immune system”), leaving hospital with prednisone taper. For a few weeks I’d wake early each morning and with push from vitamin P, bring the computer to bed where I’d stretch out and make myself write. I’d asked some questions about photography and accident, about what it meant to my four writers; I’d laid down a gauntlet or two. And while the “decisive moment” metaphysics of accident might have been a red herring, it nonetheless pointed me to contemporary photographers whose work is compelling and vibrant. To those already mentioned (Peter Hujar, Zoe Leonard, Kerry James Marshall, David Wojnarowicz, Francesca Woodman) I’ll take the opportunity to add here: Liz Deschenes, Jitka Hanslova, Hanna Liden, Claire Pentecost, James Welling. In these artists I intuit, wholly from the gut, a love for “the aged and the yellowed,” what Barthes, unabashed in his essentialism about photographs, identified in a 1979 lecture as the “real photography,” unlike the glossy pictures in Paris-Match.

Notes

I still haven’t come across that lost reference to clocks. I did, however, begin to read Walter Benjamin’s correspondence, and in a letter to Gershom Scholem dated December 20, 1931 (the same year “Little History” was published), he describes his study, a room with a panoramic view from which he can see the ice-skating rinks, as well as a clock: “as time goes by, it is especially this clock that becomes a luxury it is difficult to do without.” Benjamin also tells Scholem: “I now write only while lying down.” I think of Leibovitz’s photograph of Sontag on her bed. I don’t have the photo before me—it’s another absent picture—but perhaps I can conjure it from memory: Susan in jeans, white shirt, and dirty white sneakers, reclining on the left, her hair thick and wiry, black with white stripe; and, spread out over more than half the bed, a complex patchwork of ruled pads with half their bulk folded over, typescript pages crossed out and annotated, and oddly shaped scraps of paper with handwritten notes.

Moyra Davey

New York, July 2007

*This text is an edited version of Moyra Davey’s essay “On Photography & Accident”, 2007

Talia Chetrit, Street Self-portrait #1, 2015

Talia Chetrit, Street Self-portrait #1, 2015

Talia Chetrit, Parents, 2014

Kate Newby, Do more with your feeling, 2016

Kate Newby, Do more with your feeling, 2016

Kate Newby, Do more with your feeling, 2016

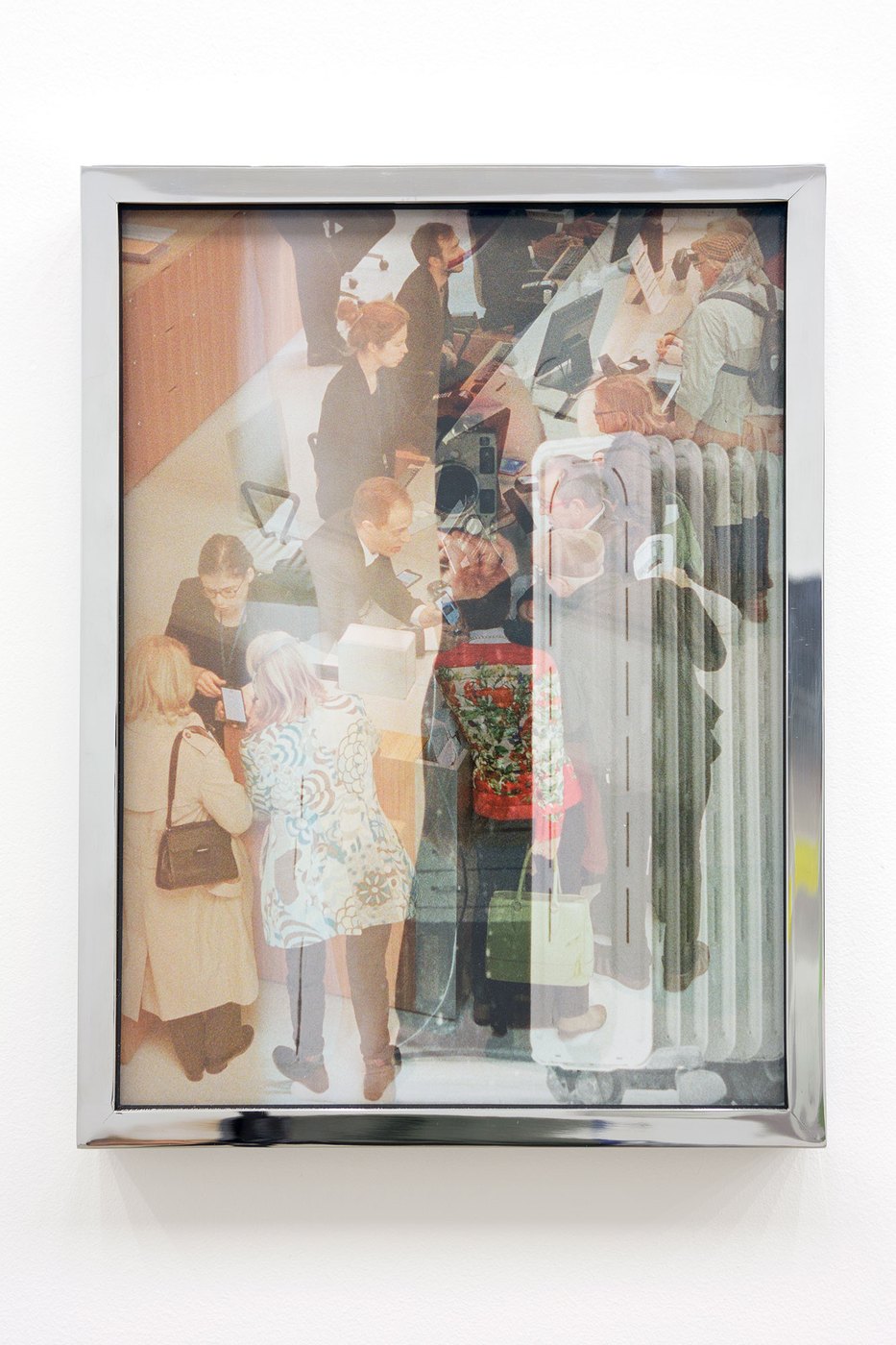

Barbara Kasten, Transposition 14, 2014

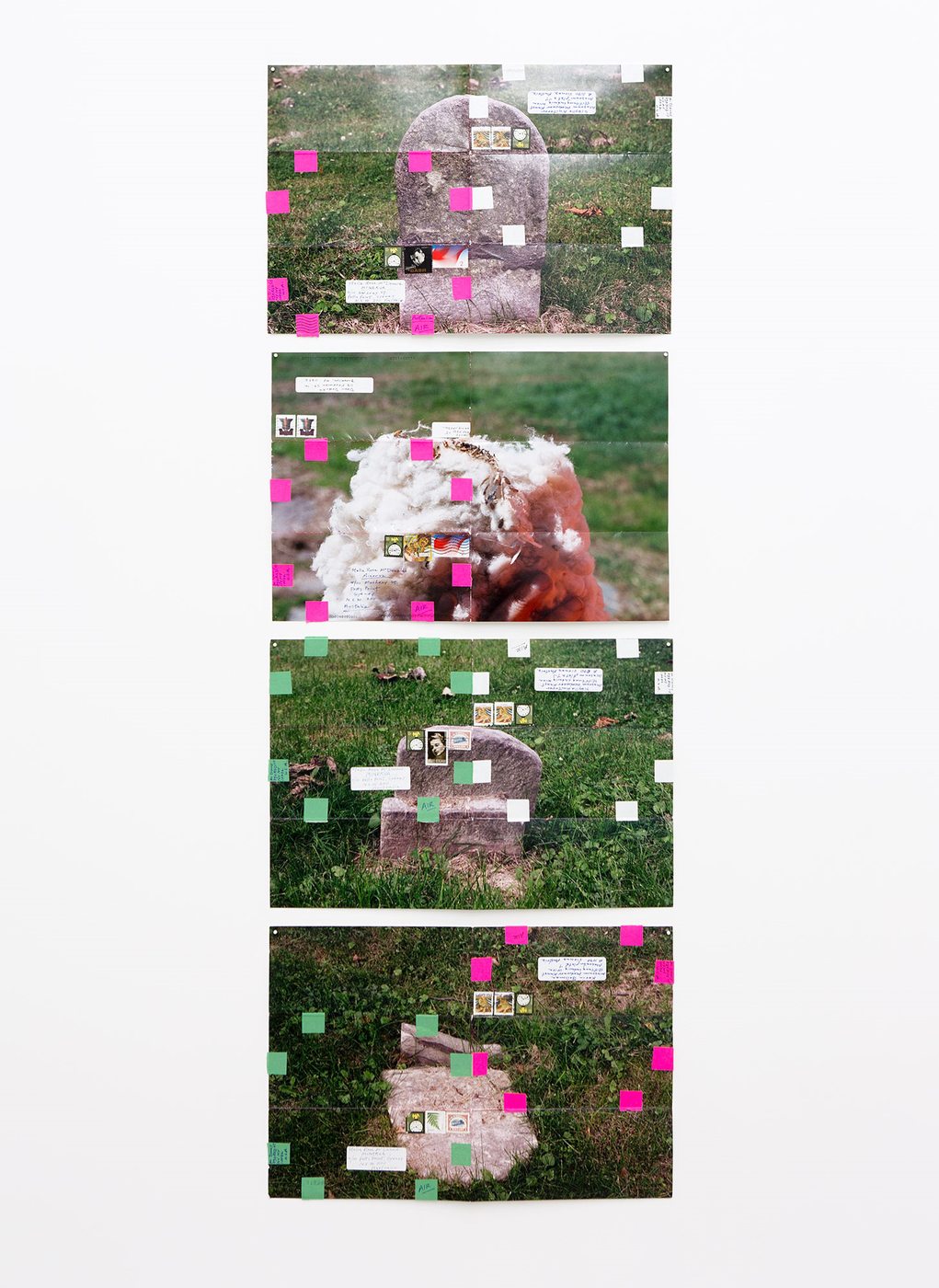

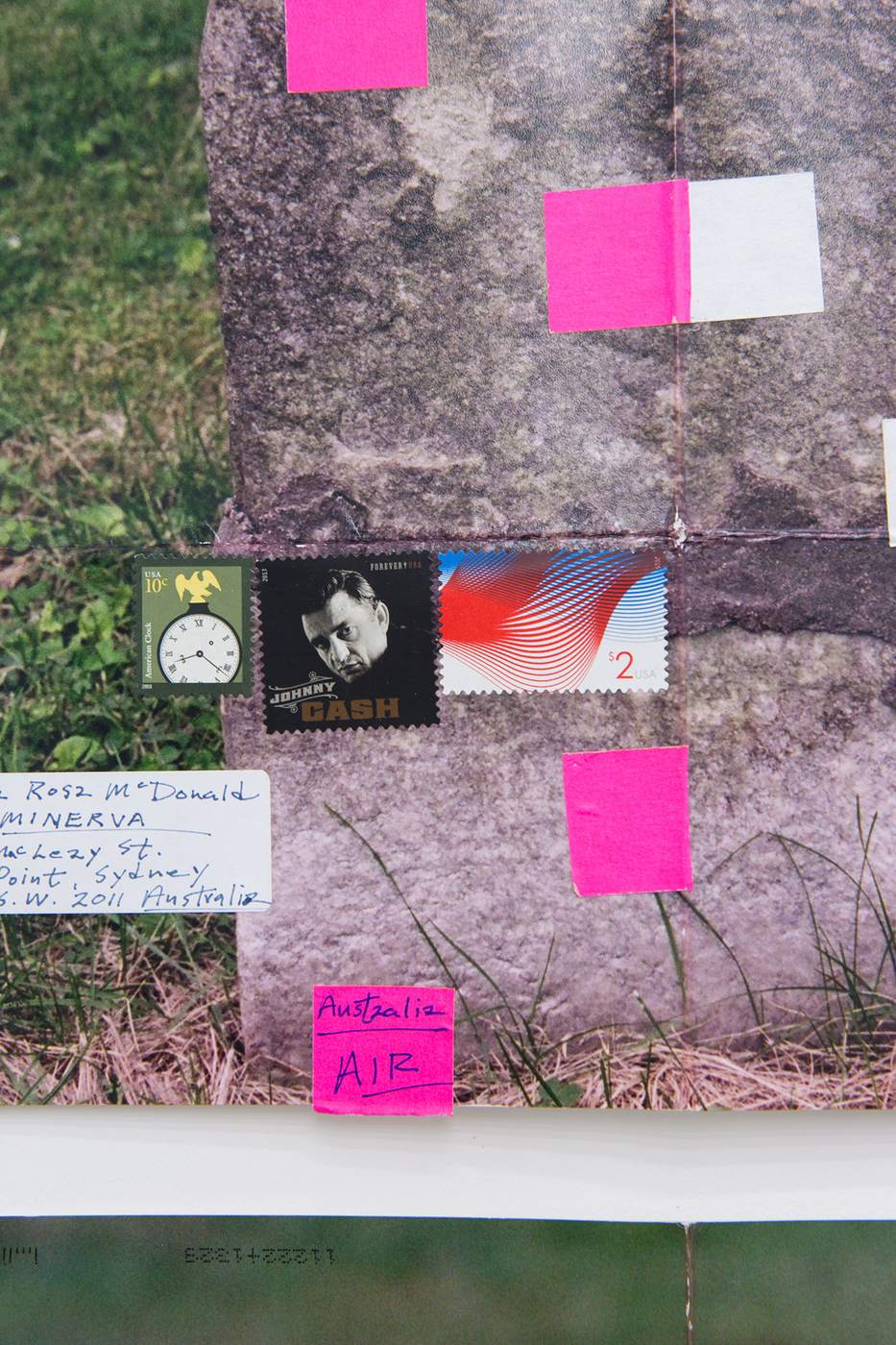

Moyra Davey, E-e-e-l, 2014-2016

Moyra Davey, E-e-e-l, 2014-2016 (detail)

Moyra Davey, E-e-e-l, 2014-2016 (detail)