Artist: Eva Koťátková

Venue: CONVENT, Ghent, Belgium

Date: October 5 – December 9, 2018

Photography: all images copyright and courtesy of the artist and CONVENT, Ghent

For the opening exhibition of the third year Convent presents a solo project of the Czech artist

Eva Koťátková (°1982, Prague), who lives and works in Prague. Koťátková, who spent a part of her childhood under the communist regime in former Czechoslova-kia, examines in her work how an individual relates to social systems and institutions such as a govern-ment, schools, hospitals, communities or family. In a wide array of media, including collage, sculpture, performance and film, or in combination, Koťátková represents the invisible: thus trying to expose power structures behind rules, conventions and rituals and materialising a feeling or situation that results from restrictions. In 2013 the artist was internationally acclaimed for her impressive installation Asylum, consisting of countless small objects and illustra-tions from medical textbooks spread over a platform, which was shown in the central exhibition The En-cyclopedic Palace at the 55th edition of the Venice

Biennale. Resulting from multiple visits to the psychi-atric hospital Bohnice, just outside Prague, Asylum illustrated a variety of delusions, phobias and fears of patients, as well as their struggle to communicate.

The sculptures and collages included in the exhibition at Convent, located in the building of a former school, also expand on this and show the possibilities and impossibilities of mental and physical limits imposed by rules that are connected to institutional contexts, ideologies and codes. The three metal sculptures Emil, Shoe and Mouse, all from 2015, were designed based on book illustrations of old animal traps. They are a continuation of earlier sculptures in which Koťátková examined structures of entrapment that were reminiscent of outdated orthopaedic devices or old-fashioned tools for psychiatric patients. For her these works aren’t about physical confinement or violence, rather they evoke the invisible, mental cages that every person carries with them and that are intensified by inner fears, often brought about by unfulfilled expectations created by society. Through-out her work there is a remarkable tension, that goes back and forward between the imaginative dream world (of a child) and the constant threat of the estab-lished structures to destroy these dreams. Koťátková frequently has her installations activated by perfor-mances. Adversely, works like Emil and Mouse seem to suggest the absence of a body and are in a way reminiscent of an action that has just taken place.

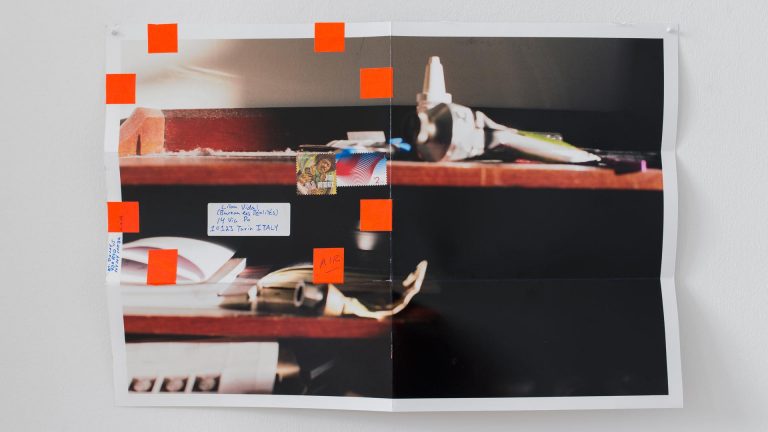

For the collages in Untitled (2014), which are spread out as a leporello on a wooden table top, Koťátková made use of photographs from historical books and magazines on psychology, medicine and education, which she has collected obsessively over the years. In this never before exhibited work she, amongst other things, combines portraits and (fragments) of the human body with images of architectural con-structions, animals and primitive masks, rendering the characters anonymous and creating a surreal world. Here too the cage is a recurrent shape. By ap-propriating, opposing and re-contextualizing existing imagery, not only new associations are formed but simultaneously the familiar appears odd.

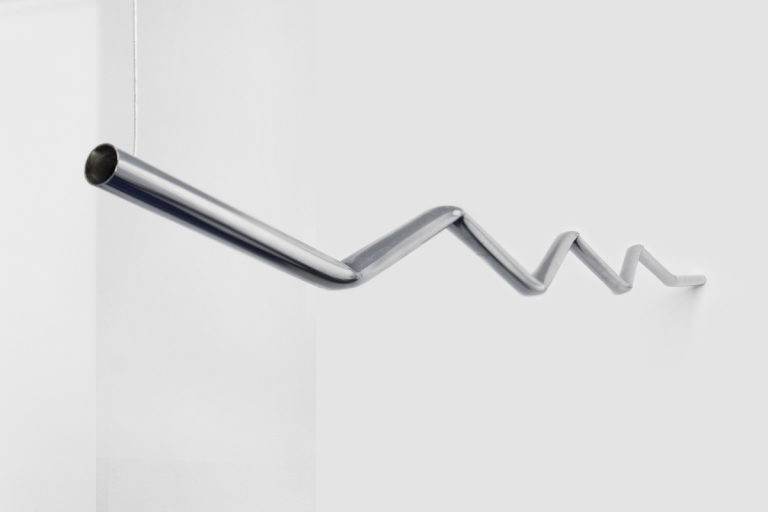

The oversized steel scissors titled Training in Ambidexterity (2015) is part of a series of works with the same title, consisting mostly of collages and other enlarged measuring instruments used at school, such as a drafting compass and a protractor. Ambidexter-ity describes the phenomenon that someone is both left- and right-handed. However, most of the people who are considered ambidextrous are not born this way, but are predominantly left-handed people who were forced, usually at school, to use their right hand. For Koťátková ambidexterity is a thankful phenome-non to demonstrate the discrepancy between, on the one hand, innate skills and, on the other hand, what according to certain institutions is the norm and thus should be taught.