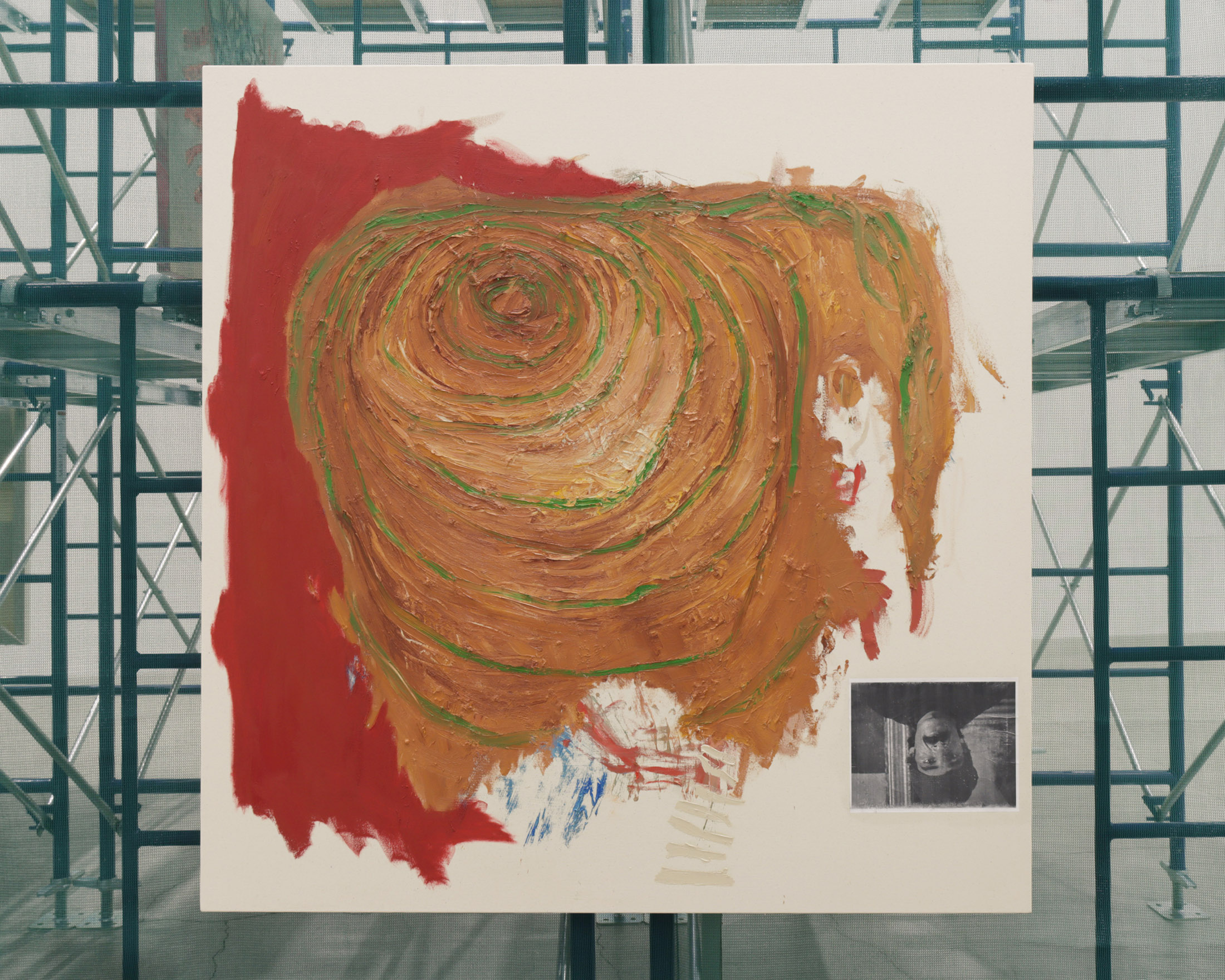

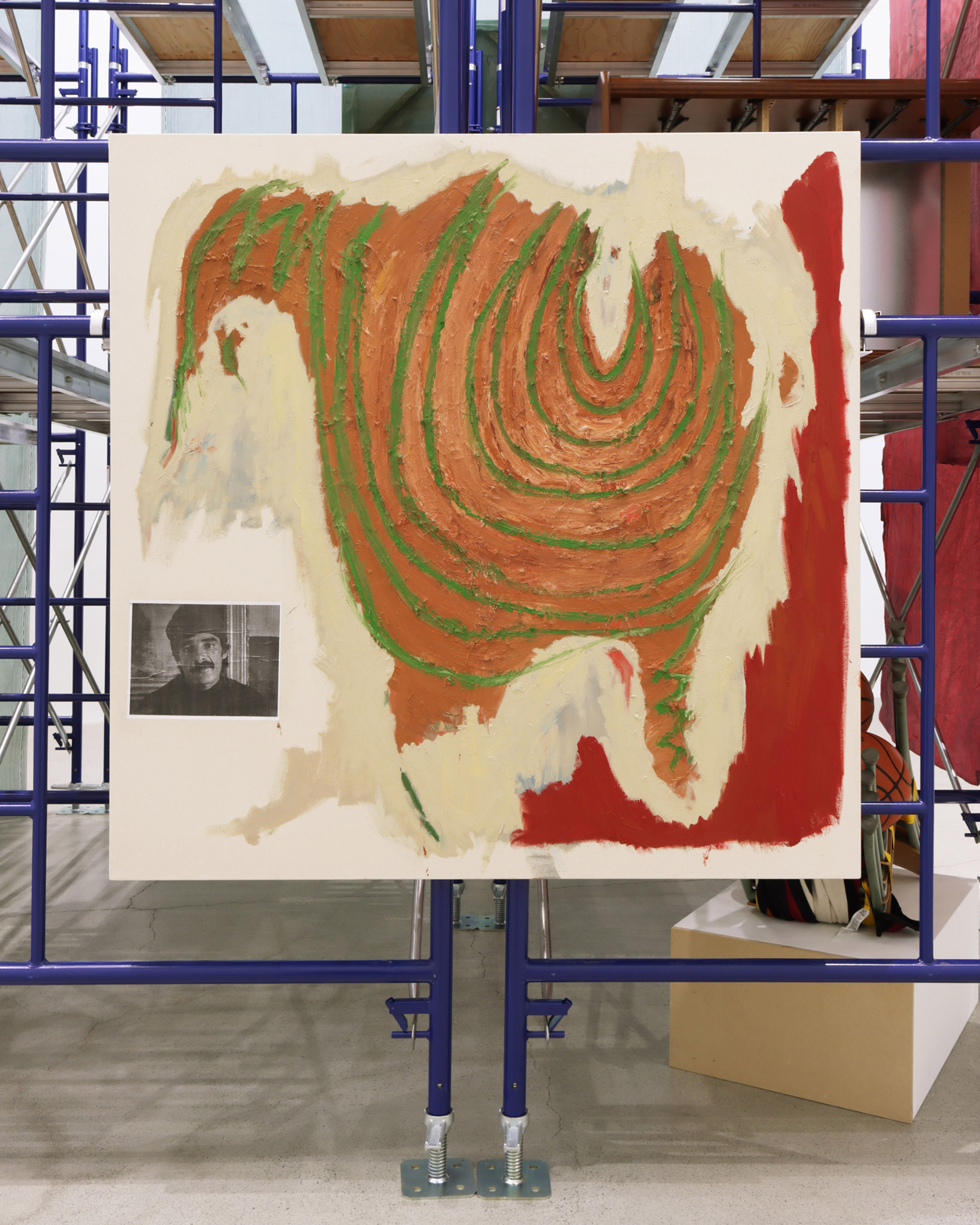

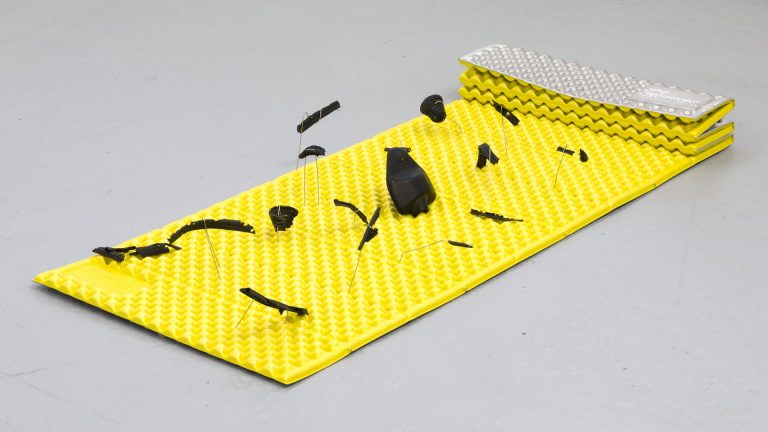

Artist: Duane Linklater

Exhibition title: cache

Venue: Catriona Jeffries, Vancouver, Canada

Date: April 5 – June 28, 2024

Photography: all images courtesy of the artist and Catriona Jeffries, Vancouver

Note: Full press release is available here

The kick drum resounds—one echoing hit is punctuated by two eighth notes before a brassy snare maxes out the headroom on the fourth beat. And it repeats. Not just for the duration of one song, but for many. By some counts, more than 70 commercial recordings make use of the iconic drum intro of The Ronettes’ “Be My Baby” (1963). Most notably, perhaps, is its appearance in The Jesus and Mary Chain’s “Just Like Honey” (1985), with the accompaniment of screeching guitars and reverb-drenched vocals. The beat originated when session drummer Hal Blaine dropped his drumstick on what would have been the second beat’s snare hit, only recovering for the fourth. What results is an expansive play of tension and release within the same measure. For The Jesus and Mary Chain—young Scots fueled by Jobseeker’s Allowance quoting doo-woop rhythms with distorted feedback standing in for lush orchestration—the drum kit is reduced to only those elements necessary to play this beat, a floor tom and snare, just as the bass guitar lacks all but the two strings necessary to carry it on.

A similar economy characterizes the work of eagles with eyes closed, the musical project of Duane Linklater and his son, Tobias Linklater. In 2021, following the introduction of sparse guitar phrases and slow, polyrhythmic percussion, Duane and Tobias use Solar cymbals to trace circles on top of (or underneath) a projection of Nancy Holt’s film Sun Tunnels (1978). Lumbering bulldozers shovel rocks while arc welders hiss as Holt’s landmark earthworks take form in the Utah desert. From their studio in North Bay, eagles with eyes closed’s improvisational score becomes saturated with delays and echoes while the Linklaters’ circular drawings begin to mimic the cruciform north–south east–west layout of those windswept concrete cylinders. Eventually, Tobias begins to smear the wall markings, darkening the concentric intersections. The film’s end titles note “inside the tunnels it is cool during the day and there is an echo.” The echo persists the 43 years between Holt’s film and eagles with eyes closed’s response at the invitation of the Dia Foundation, just as it echoes backward, too, before the arrival of the bulldozers, or the naming of the Great Basin Desert. At first blush it sounds sublime, like the wind, but each resounding echo picks up the sonic properties of concrete, bell brass, distant freeways and border fences.

Here, under the title cache, towering scaffolds rise as an inversion within the gallery space. Typically seen on the exterior of buildings in a careful gridding that facilitates the conservation of heritage facades, these scaffolds cluster equidistantly from any walls. Entrusted with another form of conservation, domestic objects and familial belongings are hoisted up and out of reach, awaiting future use. Among the artifacts selected for inclusion is a copy of “Just Like Honey.” Duane borrows from inherited cache practices to point to a circularity of energy, temporal rhythms that persist despite the screeching machines and rumbling earthmovers that alter landscapes beyond a seasonal shift.

Last year, a cache was uncovered at the confluence of three major river systems near Ottawa, revealing Indigenous artifacts and quartz tools dating back 10,000 years. Around the same time, another cache of precontact artifacts was found in an office suite on Parliament Hill. These tools will not be taken up in the way they were laid down—their next home is to be decided among local nations and national museums. But the cache is not prescriptive. That which returns from safe keeping resonates with new significance, just as that which we now deposit into the earth will one day return to a cycle transformed.