“but there are new suns”: Drew Spielvogel’s Destiny hope despair alistair

-Phillip Pyle

We approach our destination like an asymptote. The horizon lowers, the clouds drop, the vibrations stabilize. It’s right ahead of us, the shimmering object promising the realization of our deepest desires.

We’ll never get there and we know that, but it’s better to delude ourselves for now. To reveal the impossibility of that object would only reveal the impossibility of life. We’ll ultimately make these drives again and again, either settling into the depressive doldrum of the route’s ceaselessness or crashing off the course entirely.

Normality and habit can often be violent, not only in mundane ways. We don’t need queer theory to tell us this, but its practitioners do help us to see potential circumventions. Muñoz tells us that “the here and the now is a prison house,” Sedgwick that there is “no unthreatened, unthreatening conceptual home for the concept of gay origins,” and Halberstam that the norm of seriousness “means missing out on the chance to be frivolous, promiscuous, and irrelevant.” If the present, full of the crushing weight of imperatives to be habitual, serious, and obedient to an extractive political economy, is a prison, then why do we continually fall into its rhythms? Yes, those same practitioners gift us models for suspending straight time (in terms of literature, art, and performance), for embracing failure rather than treating it as a mere negative, and for locating meaning and identity in the interstitial rather than in points in a linear narrative—but the question of why we continue to fall prey to the inevitably hollow promises of normality and even optimism remains elusive.

The American Dream is one of those “normal” objects that is chased day in and day out, regardless of the impossibilities it bares with more and more gangrenous tint year after year. Lauren Berlant attributes its endurance to today’s cruel optimism, the condition that exists “when something you desire is actually an obstacle to your flourishing.” The late affect theoretician’s eponymous 2006 essay and 2011 book focus on this seemingly irrational phenomenon, where we incessantly look to the same persons, institutions, ideas, texts, and routines as beacons worthy of optimistic attachment despite our vague understanding that something will inevitably go wrong or different than planned in our quest to attain that object. For Berlant, this is partially because objects of desire less hold single desires than they do “clusters of promises we want someone or something to make us and make possible for us.” We replay them, go after them repeatedly, even relive their traumatic consequences because of the promises we cannot let go of.

That “the conditions of ordinary life in the contemporary world, even of relative wealth as in the U.S., are the conditions of attrition or the wearing out of the subject” is sobering, but Berlant also offers us examples of just what may occur in those moments when habit is suspended in its reproduction. Calling these undramatic breaks in daily routine “impasses,” Berlant looks to three textual examples where transitional moments occur “between a habituated life and all of its others.” It’s in these nonspaces that a new visitor, a new sensorial experience, or an unexpected finding interrupts the monotonous flow of things, re-fortifying the attachment at the same time that something else briefly appears possible.

“Be open to he who comes up to you. Be changed by any encounter. Become a poet of the episode, the elision, the ellipsis…” Berlant’s reading of an unnamed John Ashbery poem— wherein the narrator, somewhere in the flow from home to hymn to hum promised by the vague suburban American landscape he inhabits, unexpectedly experiences a moment of queer coupling (“He came up to me”)—marks the same kind of cruel optimism to be found in Drew

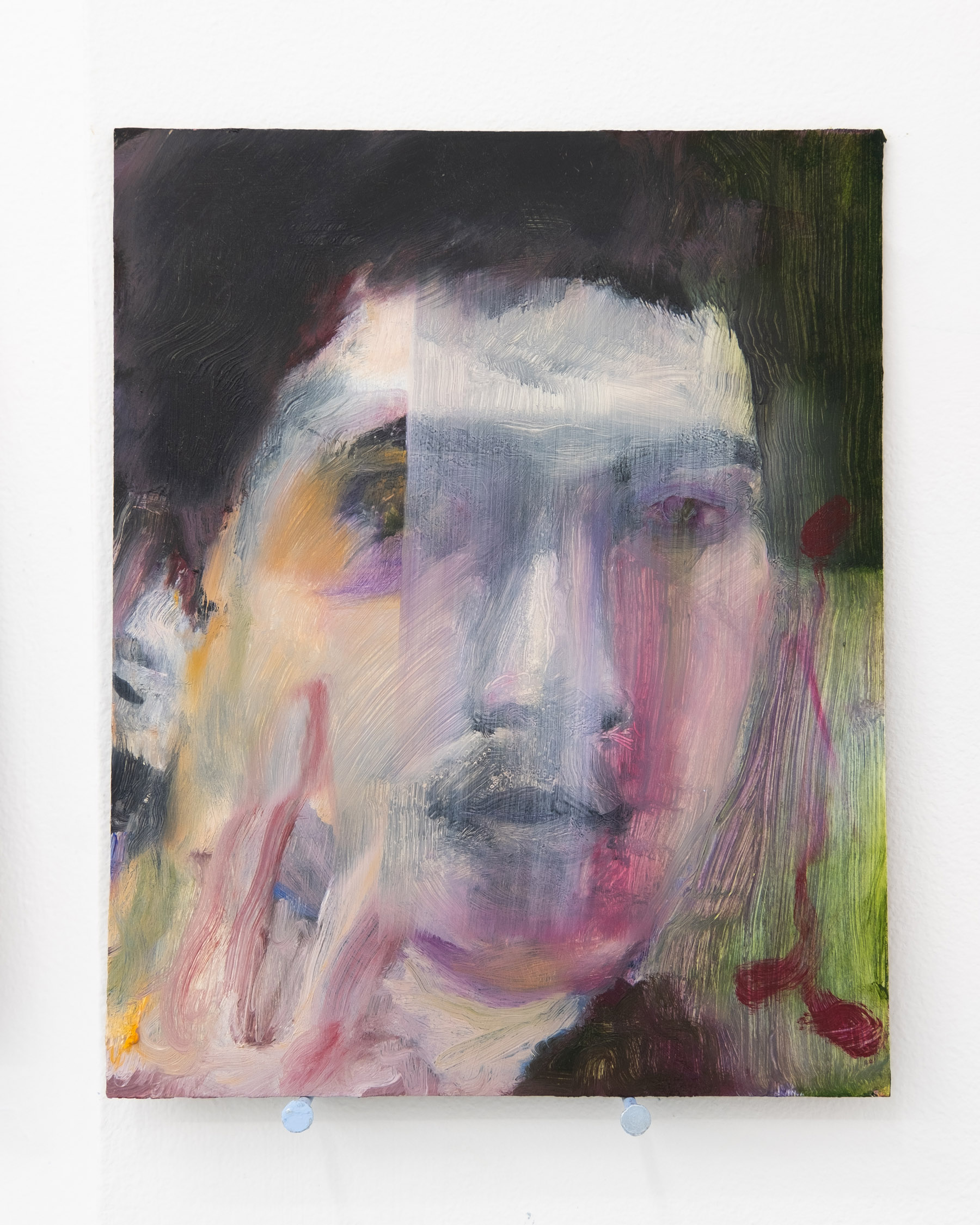

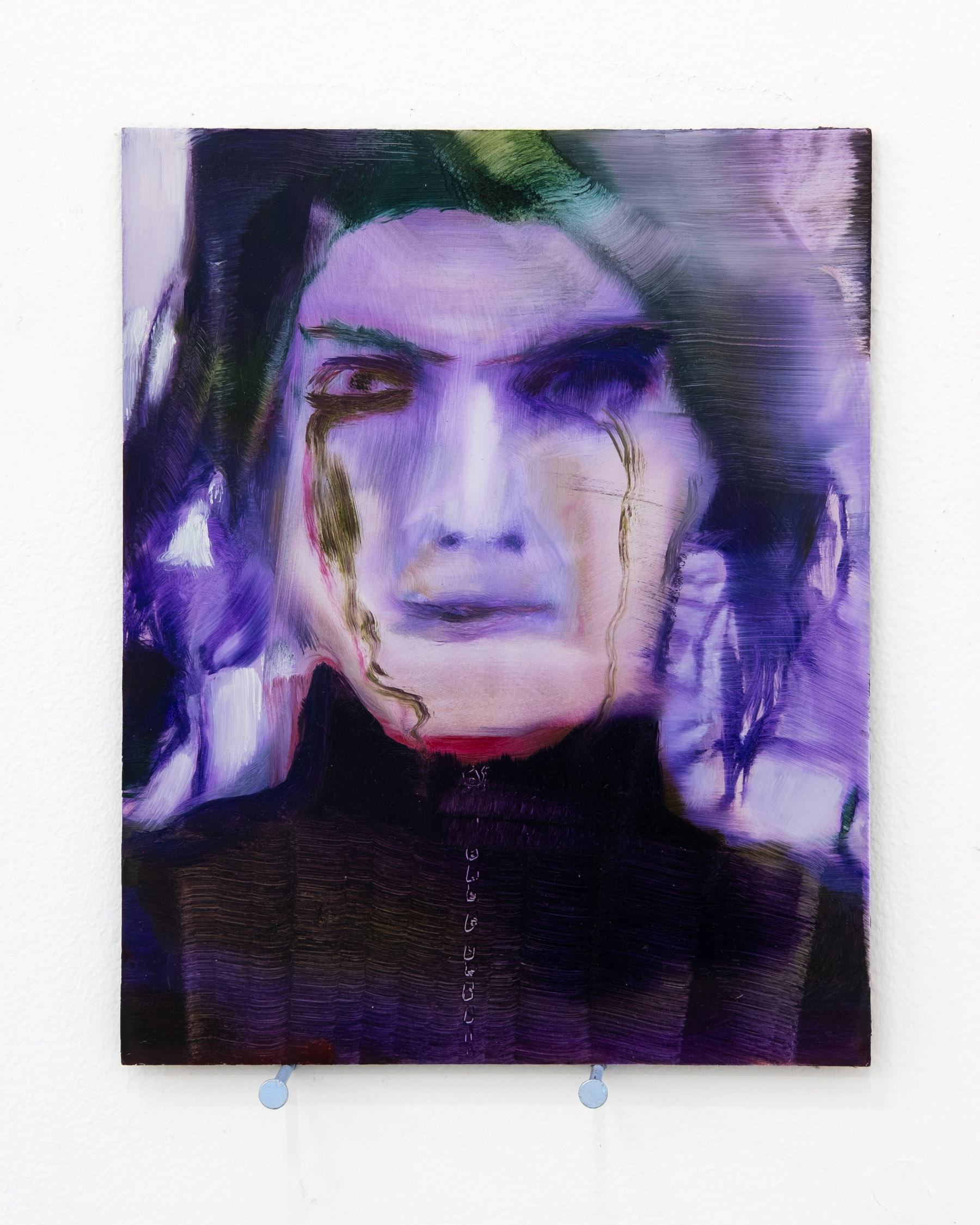

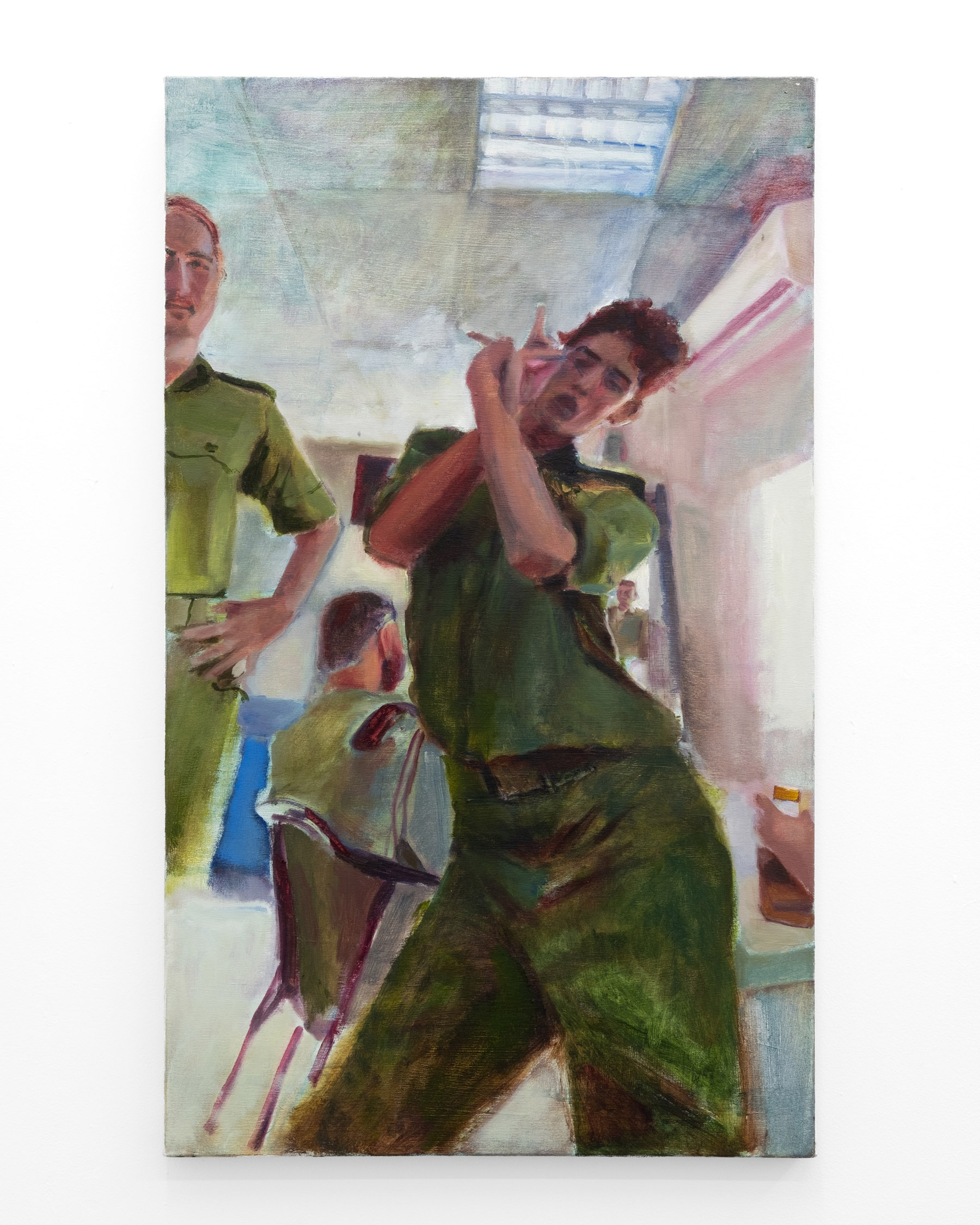

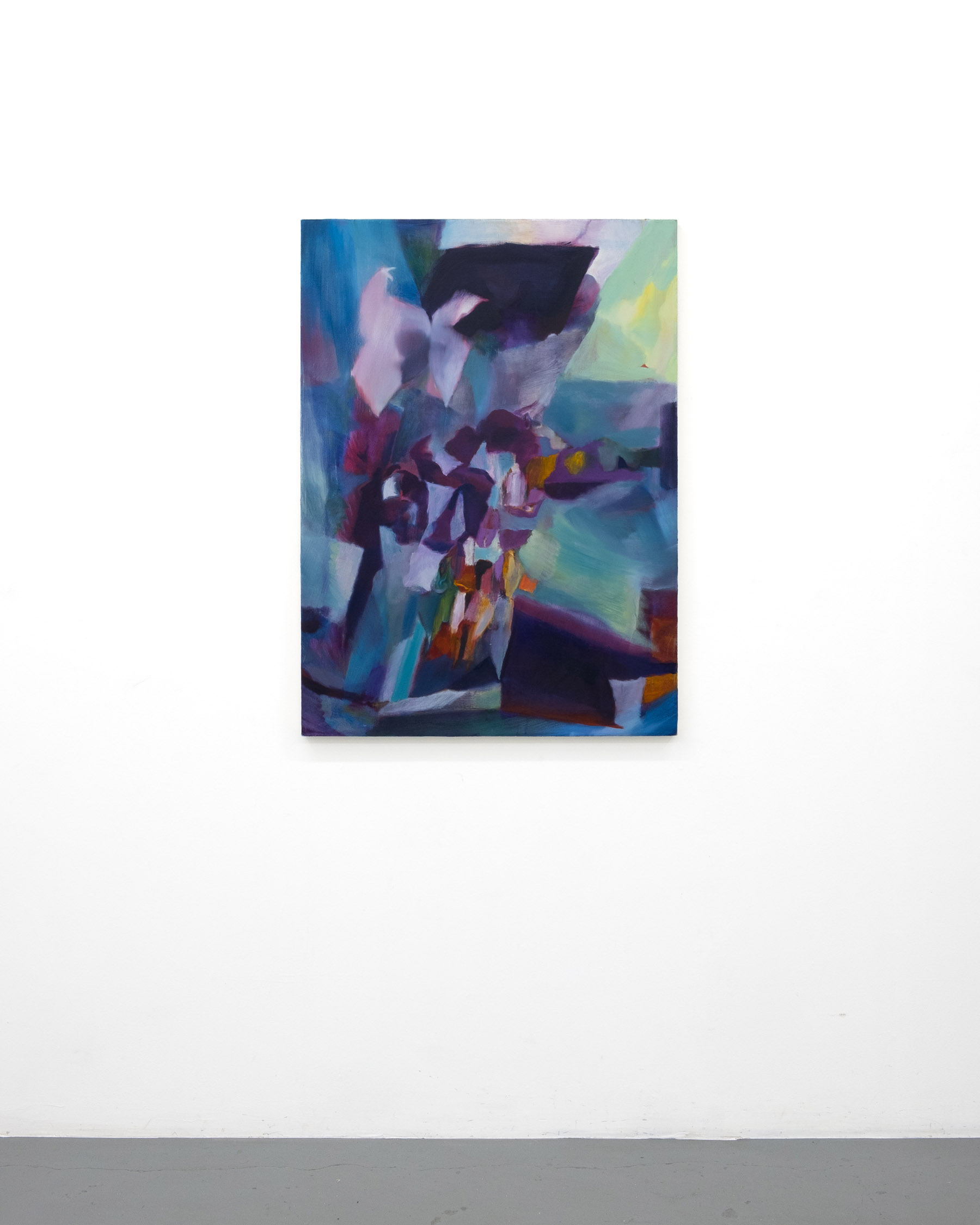

Spielvogel’s Destiny hope despair alistair. With the show’s title itself following the sequence of our attachments—to particular forms, memories, images, lovers—which begin from hope only to often waste into its opposite, Destiny hope despair alistair is premised on sets of contradictory actions. Spielvogel emphatically covers carefully worked forms with color fields, introduces moments of painterly clarity amidst atmospheric fugues, and even shreds a collage an ex made him both to fashion a new abstract composition and to reject the (R/r)omantic.

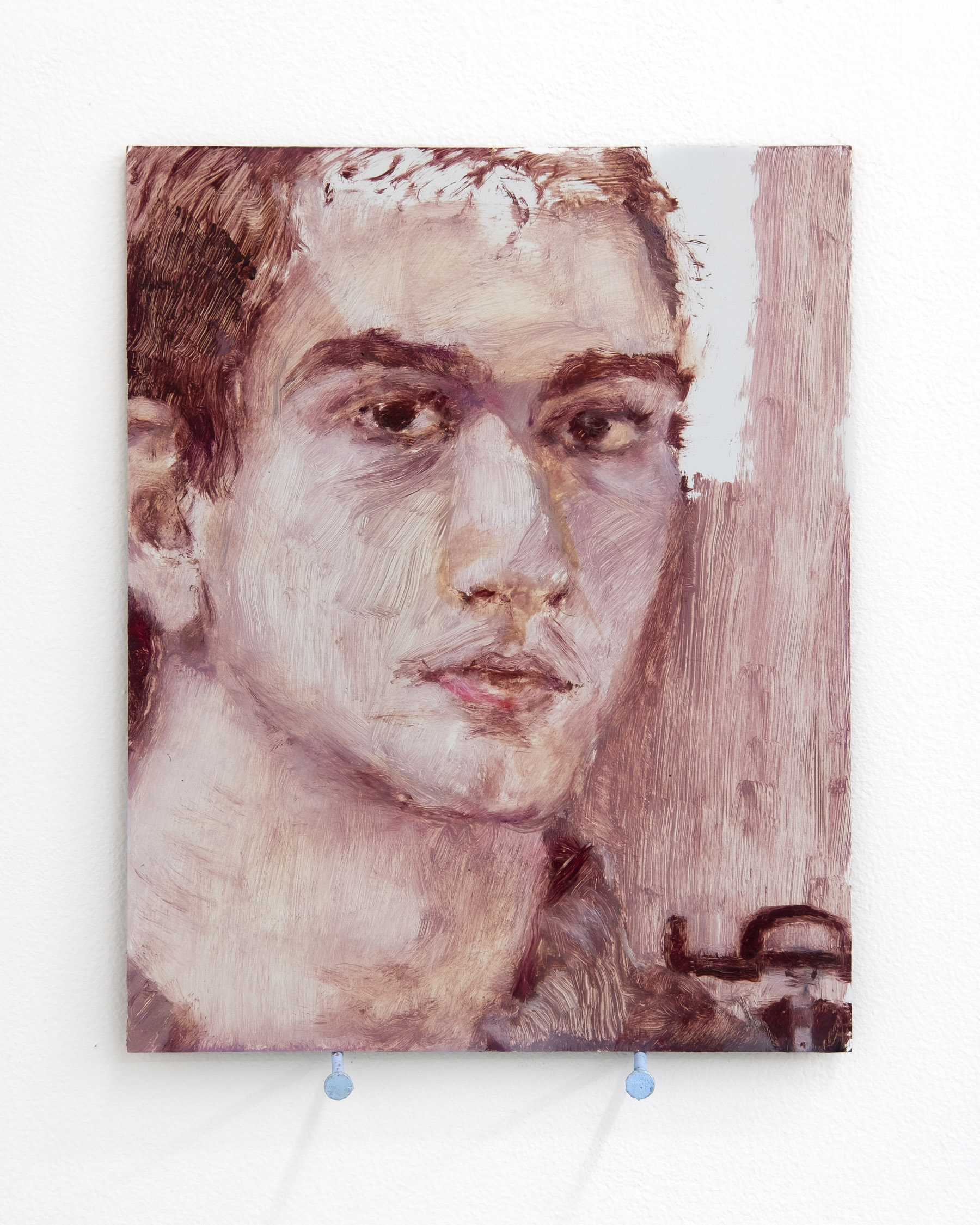

Even when he rips the form of his attachments apart, Spielvogel still cannot entirely shake his fixation with “compromised conditions of possibility.” He knows that particular memories, processes, and emotions will inevitably change course or let him down once again, but that doesn’t stop him from revisiting them. In fact, through reproducing his attachments—and the promises nested within them—Spielvogel also comes to develop something beyond a purely habitual relationship with them. His roadside painting of Christ is one such example. Pulling from the images he encounters on his commute to the cocktail restaurant in Bellefonte, PA where he works as a waiter, Spielvogel begins with what could be a familiar landscape. Instead, he leaves us with a magenta dream. Rural Pennsylvania houses fall like dominos out of the lower right corner. Mary carries a lifeless Jesus with his crown of thorns on a billboard topped by power lines. A cropped and more vivid Christ dominates the lower center. His crown has been removed but he’s just as lifeless. He’s gaunt, rendered in the purples of memory rather than those of regality. A building of indiscernible use rises out of the oblivion to the left of him. Above that, clouds become skulls. Christ is already dead, so why the memento mori? For Spielvogel, it seems less to do with a personal fear of death or an atheistic reading of the martyr’s death, than it does a coming to terms with the deadening element of our attachments. Berlant tells us, “The promise is everywhere, and the dissolution of the form of being that existed before the event is not cause for mourning or rejoicing: it is just a fact.”

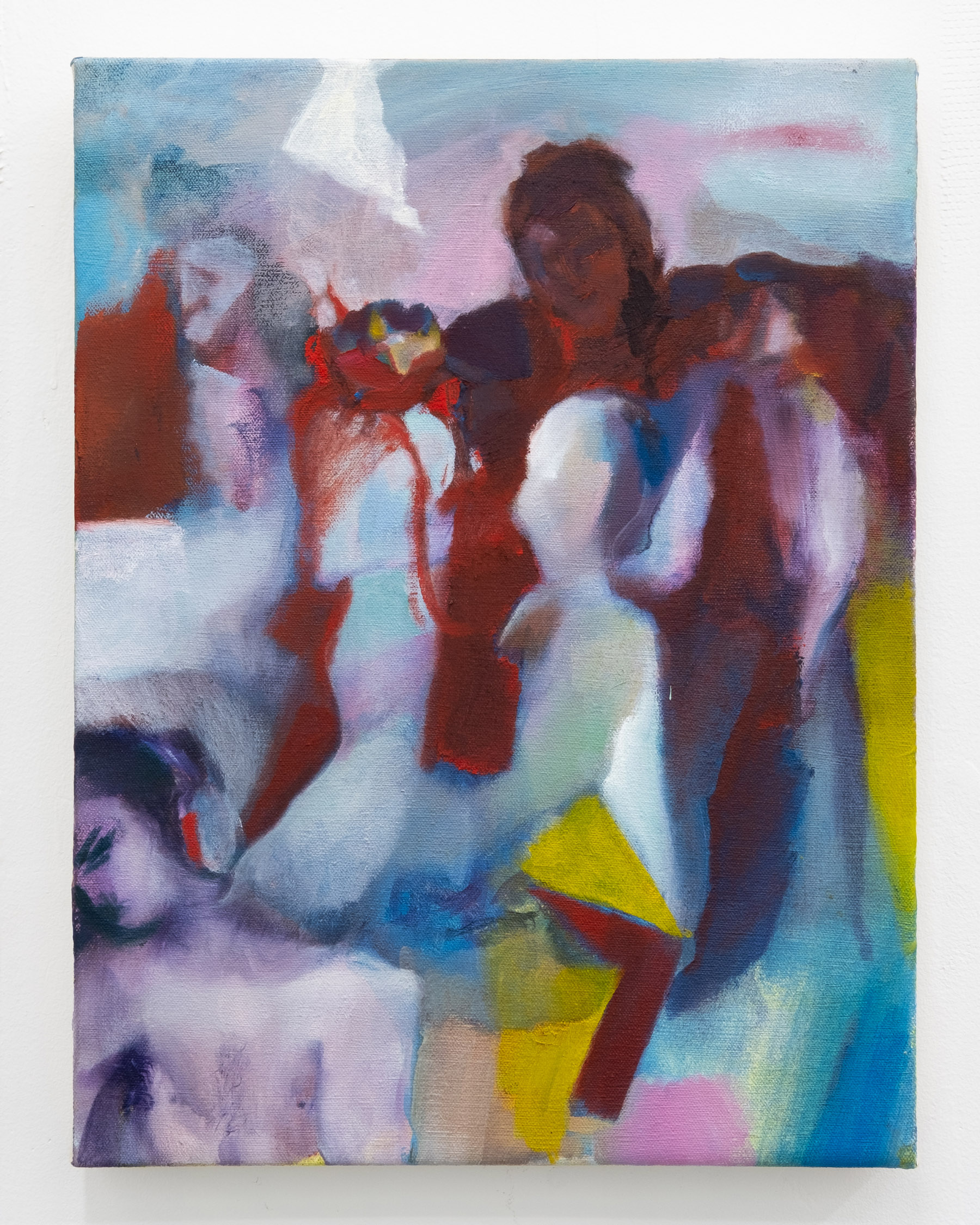

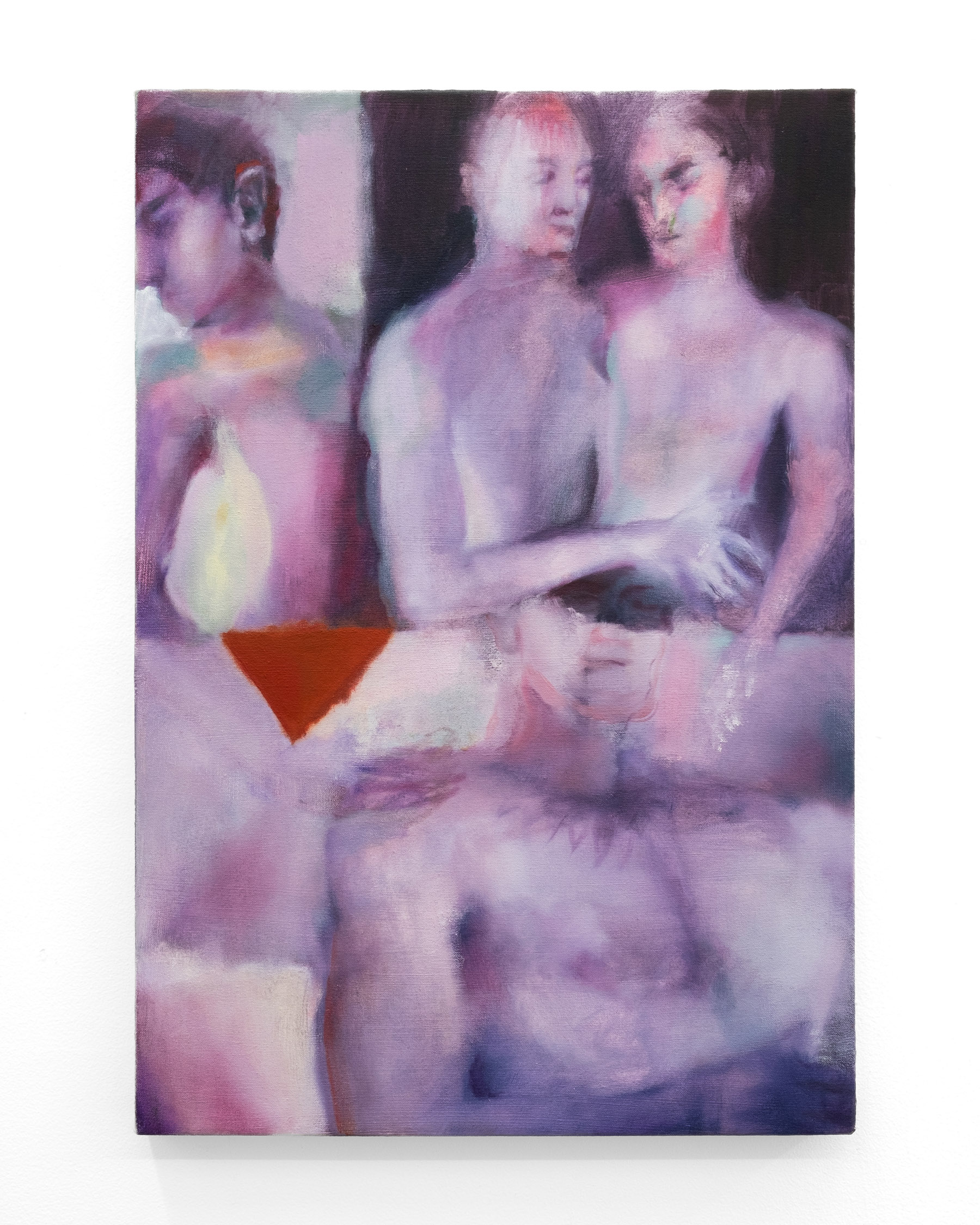

Though reproducing the objects of his desire often results in the release of optimism’s “overwhelmingly negative force,” at times, Spielvogel’s ability to “hold a nonspace without being meaningful” translates into the emergence of a less routine (and a more joyous) life. In his painting Baptism, that non-habituated life forms something like its own language. The vaguely contemporary scene takes place in a nondescript club setting, with two women in the foreground gossiping as talking heads and six men conversing on the second-floor balcony behind them. The figures may appear entirely fictitious, but to the queer eye, they are deliberately referential. The winged figure on the upper left conjures something between the Berlin angel Damiel of Wim Wenders’ Wings of Desire (1987), the twink angels of Isaac Julien’s Looking for Langston (1989), and a queered vision of John the Baptist. In the foreground, obstructing the face of the central left figure, is a miniature portrait of the science fiction author Octavia Butler.

Here, Spielvogel’s language resembles something along the lines of Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari’s idea of a minor literature. Defined as “not the literature of a minor language but the literature a minority makes in a major language,” a minor literature has three main characteristics: “the deterritorialization of the language, the connection of the individual and the political, the collective arrangement of utterance.” Untethering references from single contexts, elevating personal references to the language of politics, uniting them under a communal (but not necessarily universal) roof—this is what Spielvogel’s interest in attachment and cruel optimism reaches toward, too. Yes, failure will occur in the process—as will despair, anguish, loss, and pessimism—but it’s in the reaching that other promises may emerge from the impasse. As Butler writes in the epigram to her unfinished Parable of the Trickster:

There’s nothing new,

under the sun

but there are new suns.