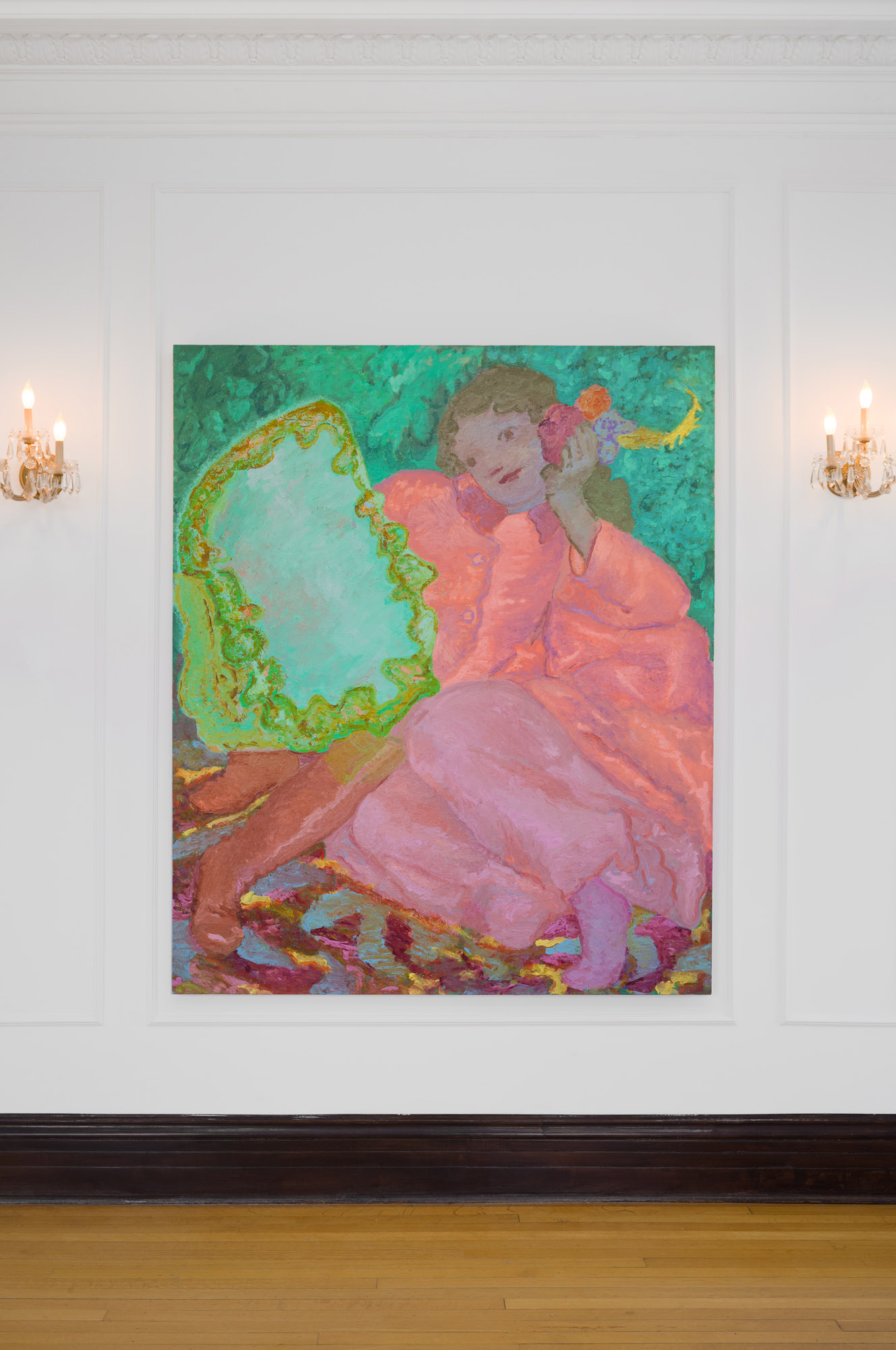

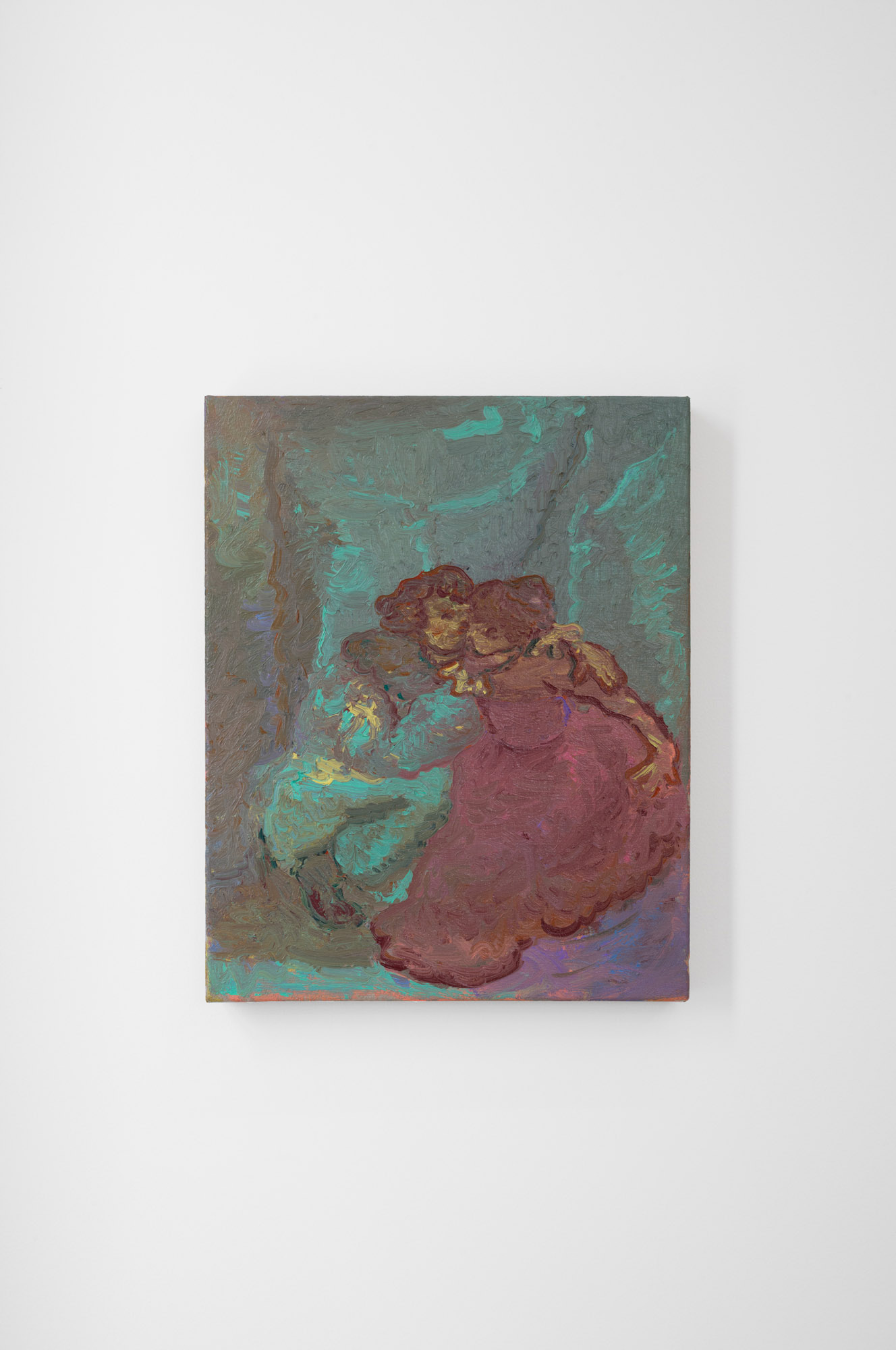

Artist: Delphine Hennelly

Exhibition title: Behind the Scenes

Venue: Pangée, Montreal, Canada

Date: January 20 – March 2, 2024

Photography: all images copyright and courtesy of the artist and Pangée, Montreal

I wish I could name the particular shade of blue-green strewn throughout Hennelly’s series of paintings. I wish I could to dive into her wellspring and spray out with its secrets, trap its greenish elixir between my palms and slip it into my own poems. But my wish is in vain. The colour slips away even from itself, travelling along the surface mirrors, landscapes and the fabrics of period clothing. It’s unclear where the green begins and where it fades into the sky, because it’s turquoise, but not exactly. It’s cyan, but not really. It’s an aqueous shade, maybe that of a mermaid scale, or of the soft revolt of a fresh manicure bitten off and spit out.

What if this blue-green were not just a shade, but a movement?

Half-way between a robin’s egg and the blue watercress of a Rimbaud poem, the colour is a “a green hollow where a river sings”, a space-between, a passage. It flows like water, hissing while I gaze at my reflection on its mirrored surface. I transform into something beautiful. Like water, I too am in movement. The mirror is simply the last thing between me and the party.

Such indeterminate things can anguish us, and so I keep trying to pin the colour down. As soon as we name things, we succumb to a desire to neutralize them. And as we buff out their ambiguity, we put an end to their story. Like trapping an insect for observation, we render the colours we name inert. If we name a colour, we can market it, just as Tiffany Blue sells us jewelry.

The colour found in so many of Delphine Hennelly’s paintings is living, even fleeting. We might compare it to the bluish shade of the Statue of Liberty as it resembles the verdigris of humidity-exposed copper. This patina is the result of a chemical reaction—it comes from another sort of movement: the passage of time, the instability of matter.

This echoes another of Hennelly’s motifs: her ever-present curtains. My own curtains—I draw them together at sunset to darken my bedroom completely. And while the curtains stop me from seeing what goes on outside, they also contain the promise of a bright day ahead, draping over the threshold through which night passes over into morning.

Behind my curtains hides the unknown, the things that I must face to make room for my own movement, my own statues turning acid-green with their colours that vanish over time. During the Renaissance, when painters used copper acetate to make green pigment, they didn’t know that the colour would eventually oxidize. Their paintings, as such, were destined for continual metamorphosis.

My intuition is that this chemical phenomenon is a part of Delphine Hennelly’s work—she reaches backward to archetypal images to bring their oxidized forms to us. Her images seem to be subject to their own internal corrosion, always in the process of decomposition. As such, Hennelly’s paintings depict other subjects—a mother and child, still-life flowers, Fêtes galantes—but as soon as these images reach us, they vibrate upon contact and gain a certain charge. Her characters’ faces are pared down, their features swollen but sharp. Their simplified, almost cartoonish faces almost resemble emojis—inscrutable expressions, communicating what? Just as copper oxidizes, Hennelly’s scenes are in flux, beating like human hearts. Ever investing in classic themes, Hennelly attempts neither to name the world nor to capture it, rather to enclose it within its own unfathomable mysteries.

Text by Daphné B.

Translated by Catherine Ribeiro