Artist: David Czupryn

Exhibition title: Holy Ghosts

Venue: Museum Engen, Engen, Germany

Date: November 9, 2019 – January 6, 2020

Photography: all images copyright and courtesy of the artist and Museum Engen

One could think of David Czupryn’s images as painted illusions or surreal constructs that follow their own inner logic. But I’m not sure it’s enough to draw on well-worn terms from the history of painting like “trompe l’oeil” or “Surrealism” if one wants to explain the specificity of his work. Instead, when I stand in front of his canvases, I have the need to move past those familiar terms and feel out a phenomenon that I might provisionally describe as a synthesis between classical painting and the digital realm, between the canvas and the user interface. There’s already a term for it on Wikipedia: “digitality.” In German, it’s a portmanteau of “digital” and “materiality”; in English, it has the epochal undertones of “modernity” and “post-modernity.” For me, it also conjures the word “dignity,” if only by way of rhyme. Following this line of thought, the intersection of the analog and digital could thus be a way of dignifying a subject that draws on the relevant means of representing the present from each way of relating to reality; and it’s precisely these means of representation that make the present—specifically saturated as it is with life—worthy of being perceived as something of artistic value. I arrived at this idea while looking at the painting Coups de Bâtons (1937) by the Greek-French artist Antoine Malliarakis, otherwise known as Mayo, who was born in Egypt. Czupryn produced an elaborate adaptation of the image in 2018 under the title Baton Blows. But one only needs to consider the painting’s dimensions—it measures an impressive 260 by 360 centimeters—to realize that Czupryn isn’t just doing a Czerny-style study with his brush. His adaptation is a kind of program in itself, and it’s precisely its visible, minor deviations from the original that reveal this virtuoso, yet unconventional painter’s strategy. David Czupryn was born in 1983 and first trained as a carpenter before he studied sculpture and painting at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf. This particular biographical detail seems relevant, since his early familiarity with technical craftsmanship is reflected in both his work ethic as well as the material appearance of his paintings. Mayo’s paintings were conceived as a response to brutal police repression of student protests. One gets the impression that the abstract scenes of violence are all the more effective since the viewer has to induce the image’s content detail by detail. The fragmented, dynamically interacting figurative elements recount a real event by using “real” objects such as chairs, bottles, and packs of cigarettes. What, however, does Czupryn do with this model? The first thing one notices is the difference in materialities. The wood grain in Czupryn’s version points to the sphere of materials and haptic experiences. Through being made into objects, the irritating floral-ornamental and object-like aspects from Mayo’s original are further intensified. What Czupryn shows, however, aren’t figures or fragments abstracted from reality, but rather autonomous outgrowths that develop according to their own unrealistic, seemingly organic dynamic. The pictorial objects follow the structure of Mayo’s template, yet they convey little of his recourse to the protests 80 years ago. I don’t think it would be a stretch to say that Czupryn scales down the violence that permeates Mayo’s work to the level of a video game—one where zombies fight aliens, and baton blows fight the batons themselves. This impression comes not least from the mosaicked sky. Contrasted against the stage that seems to extend into the viewer’s space, the sky’s flatness underscores the artificiality of the entire scene. Standing before the painting that almost reaches down to the floor, I feel like an agent, like a player in a game whose rules I don’t understand. The precarious visual architecture stops me from diving into the visual space according to the classical rules of art. Or to say it differently: I feel like I’m logging into a visual event instead of being able to survey it from a distance. Clearly, we’re dealing with a mode of perception that goes beyond the classical dialog between observer and image. Let’s consider further details like the objects previously mentioned: the pack of cigarettes, the glass, or the bottle on the table. Unlike in Mayo’s image, the bottle here isn’t a concrete bottle with label, but rather a bottle as symbol, like the kind you might find on a smart phone’s emoji keyboard. Starting from this detail, I’d like to chart a course that takes us closer to the heart of Czupryn’s visual and artistic ideas. In the dialogue Czupryn stages with Mayo—as a proxy for classical painting, and Surrealism in particular—he confidently asserts his own position as a 21st-century contemporary whose experience of vision and reality has different preconditions: namely digitality. Here, it’s no longer about the formal-aesthetic approach to reality, whether it’s in the sense of figuration or abstraction. The foundational concepts for analyzing modern art don’t have much foothold here. In the digital age, any visual constellation is possible, and all of these constellations can be related to each other and visualized. In other words, they become real through interaction, regardless of whether they’re computer-generated or handcrafted on the canvas. Digitality means that reality’s space of possibility becomes fiction’s space of reality. When you look at several of Czupryn’s paintings in succession, you realize that the perspective, vanishing points, and centers all seem to be saying that the classical visual hierarchies have been systematically suspended. The arrangement of the pictorial objects and their interactions on flat stages resemble those of nodes in a network and more or less active visual sub-centers. The solitude of the contemplative romantic searching for meaning with his back turned to the analog world has grown passé. In Alternative Lifeforms from 2018, Czupryn stages Bruce Nauman’s ironic neon installation The True Artist Helps the World by Revealing Mystic Truths in the center of his visual sign-network. The message is clear: here, autopoiesis reigns in its purest form. The network itself produces meaning, while the image of art as the educated bourgeois producer of “mystic truths” has been exhausted. In this self-producing cosmos of digital network animation which no longer has need of any direct relation to analog reality, there are no trompe l’oeil effects—to return to my original thought—no real deceptions. Everything is based a priori on artifacts and their suggestive staging. Czupryn’s Baton Blows is thus a programmatic copy in the way it marks the transition between classical modern painting and the aesthetics of contemporary perception through a series of minimal adjustments to the original.

I have to admit that some of my provisional considerations here have left me feeling a bit clueless. How can one explain that an oil painting made with the finest glazes can no longer be read as a window or a surface, but rather as a user-interface? Or that the artist conceives of his medium as a means of performatively analyzing visuality, and no longer reality? Which factors must have come together, I ask myself, to trigger such a fundamental shift in artists’ worldviews, and not just aesthetically? All these questions seem ambivalent to me, even enigmatic. This might be because I’m still emotionally and biographically rooted in the good old analog world, and can’t understand the way digitality comes to visually produce reality. But that’s all the more reason for me to find inspiration in David Czupryn’s paintings: they teach me how to wonder.

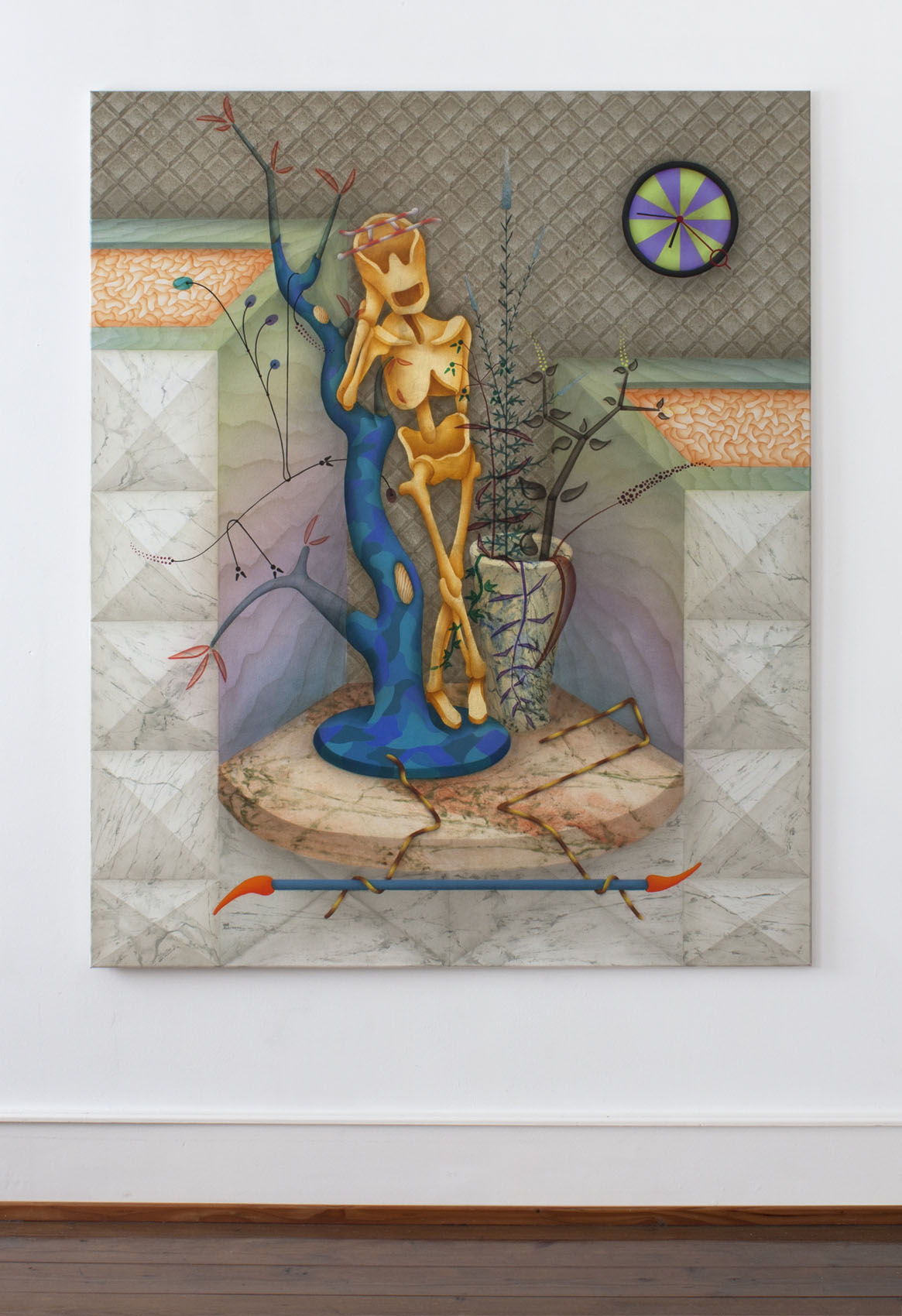

David Czupryn, Holy Ghosts, 2019, exhibition view, Museum Engen

David Czupryn, Holy Ghosts, 2019, exhibition view, Museum Engen

David Czupryn, Holy Ghosts, 2019, exhibition view, Museum Engen

David Czupryn, Holy Ghosts, 2019, exhibition view, Museum Engen

David Czupryn, Holy Ghosts, 2019, exhibition view, Museum Engen

David Czupryn, Holy Ghosts, 2019, exhibition view, Museum Engen

David Czupryn, Micha, 290 x 200 cm, Oil on canvas, 2019

David Czupryn, rising youngster, 240 x 180 cm, Oil on canvas, 2019

David Czupryn, Holy ghosts, 240 x 180 cm, Oil on canvas, 2019

David Czupryn, There is nothing left ther is no right, 200 x 250 cm, Oil on canvas, 2019

David Czupryn, Pusher, 170 x 130 cm, Oil on canvas, 2019

David Czupryn, Gamechanger, 170 x 140 cm, Oil on canvas, 2019

David Czupryn, Constructed torso, 200 x 150 cm, Oil on canvas, 2019

David Czupryn, Melancholia, 200 x 150 cm, Oil on canvas, 2019

David Czupryn, Scare crow, 200 x 150 cm, Oil on canvas, 2019

David Czupryn, Phantom & Ghost, 150 x 120 cm, Oil on canvas, 2019

David Czupryn, Me as a carpenter, 120 x 80 cm, Oil on canvas, 2019

David Czupryn, Behind the grid, 120 x 80 cm, Oil on canvas, 2019