Artist: Darby Milbrath

Exhibition title: Marne Repulse

Venue: Pangée, Montreal, Canada

Date: November 25, 2023 – January 13 2024

Photography: all images copyright and courtesy of the artist and Pangée, Montreal

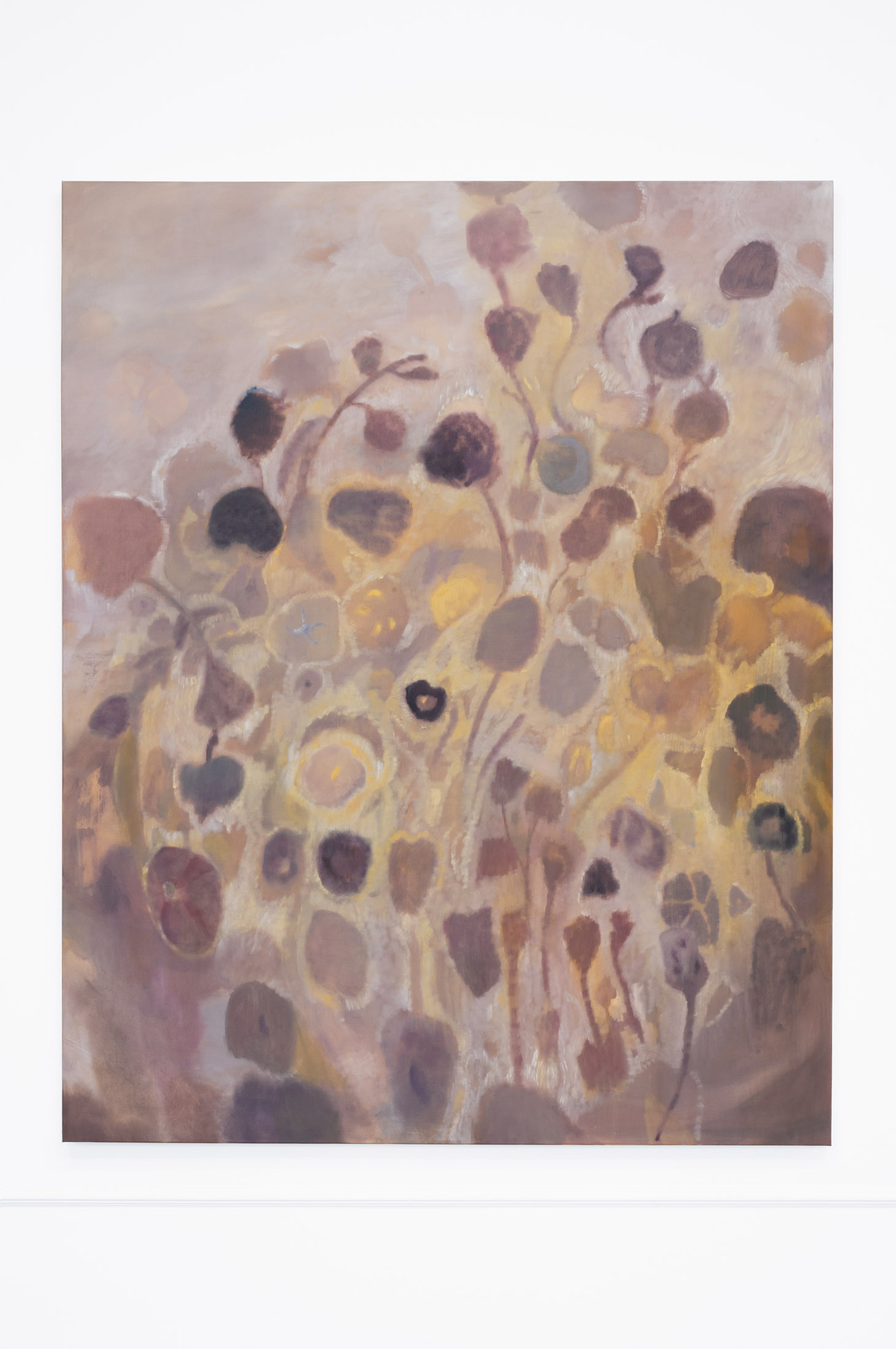

It takes me a few moments to see the girls because they are almost trees. The paintings have caught them in a state of in-between, as if halfway through undressing, mid-metamorphosis. The strictly human world lies discarded, blousy and needless. In Darby Milbrath’s blotched pansy-scapes, grounds are neither fore nor back. She has not flattened the vista, but rather, made the very distant feel prominent. The sky is at hand. Her flowers smear in stratocumulus clouds. Yellow advances, like a storm.

I want to describe Milbrath’s blooming undergrowth as gibbous, to compare the roses to moons, but then I question whether or not these shapes— convex, glowing, space-blue, edges of sun-white—are flowers at all. If the girls are just a breath away from growing branches, what are the blushing petals becoming? I’m relying on flowers to explain what I’m looking at it, to rationalize these dense coils of color. I wonder if that is what metaphor always offers us; we say something blooms, as if it is a rose, or shines, as if it a moon, and we can see it small, rustling in the wind, lining the path down to the secret beach, or reflected in the water, a sequin in the pleated waves. The object might expand through our description, its filaments weaving into a larger network of language—it is both what it is, and also a rose, a moon, doubled. But the object also narrows, pinned down to a certain type of pink in our mind’s eye. A certain type of night.

Tangles of sea-glass on stems, the dappled skin of mushrooms, with frilly undersides, or gaudy stones, embroidered with moss. Milbrath’s vistas are dense and breathing. They are horizon-less like a forest, a wheatfield, or an abandoned back garden, haunted by butterflies. What does an image of the “overgrown” promise? The inevitable skein of that which is alive, the thicket or the web, the clearing-less. Certainly, it challenges the supremacy of the figure, the human intervention upon the scene, already so emphasized by the existence of the painting itself. Perhaps it rearranges itself in history, evoking a future terrain, where girls and trees are both left to figure themselves out. Morning glories can grow roots so thick they are heavy as ropes. At dusk, the sheets of rain look like dead leaves.

In Bernini’s sculpture, Apollo and Daphne, the outstretched tips of Daphne’s fingers become verdant boughs, her floating hair curling into foliage. Her thigh is covered with a sudden sheath of raw bark. She is afraid; it is a scene of attempted rape. Milbrath’s paintings offer this type of collapse, bodies merged with a different ecological cycle, without the pursuing god, without the Apollo. One could perhaps describe her paintings as scenes of surrender to nature—a submersion, at the very least. But both these terms glint at Daphne’s terror, sharing a prefix of the underneath. How to describe a rising-to nature, an emergence? In Milbrath’s work, the light cleaves to the smallest surface, leaving a mark, the permanent trans- cription of every blossom’s whorl, every reaching hand.

– Text by Audrey Wollen