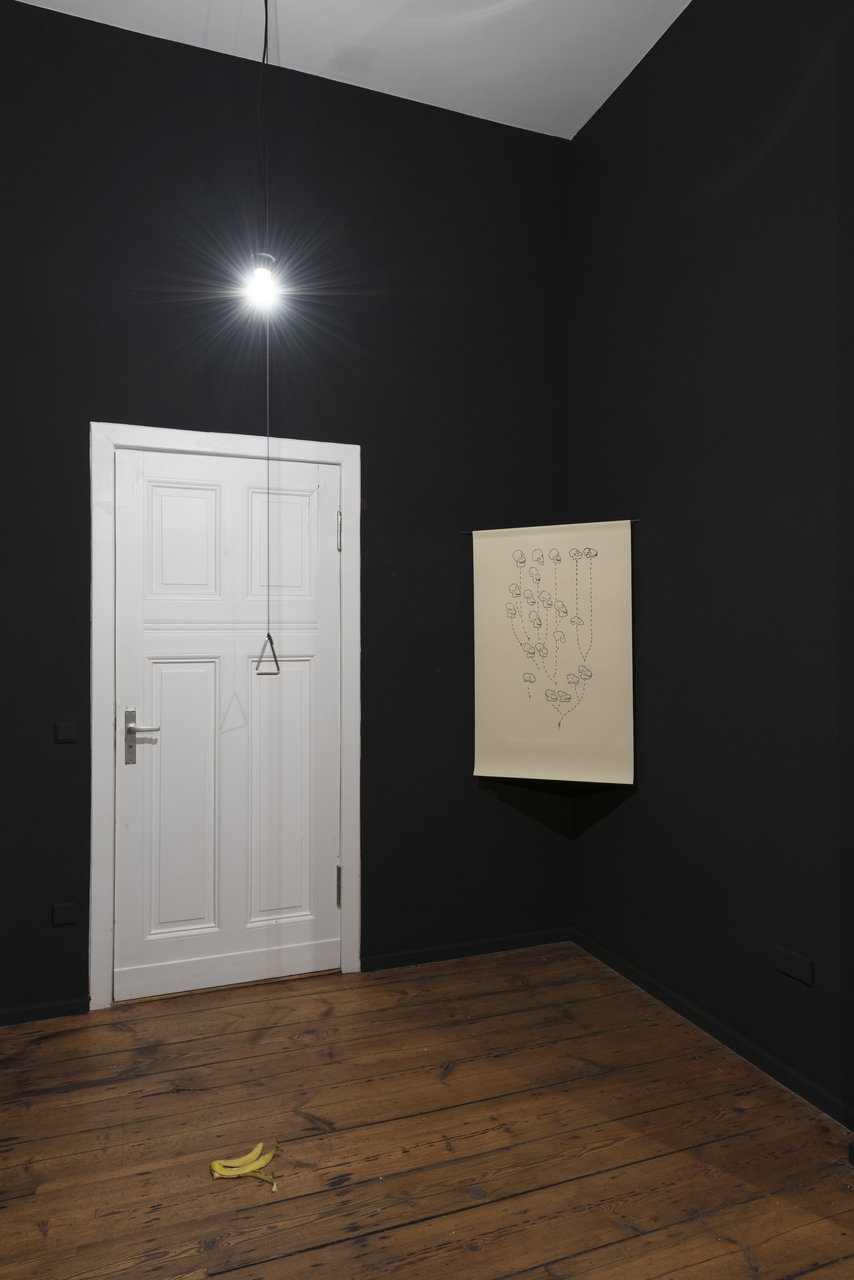

Artist: Dafna Maimon

Exhibition title: Dark Monologue

Venue: KINDERHOOK & CARACAS, Berlin, Germany

Date: March 14 – May 2, 2015

Photography: Trevor Good, images courtesy of the artist and KINDERHOOK & CARACAS

“We start out postulating sharp boundaries, such as between humans and apes, or between apes and monkeys, but are in fact dealing with sand castles that lose much of their structure when the sea of knowledge washes over them. They turn into hills, leveled ever more, until we are back to where evolutionary theory always leads us: a gently sloping beach.”

– Primatologist Frans De Waal

As a third manifestation in a series of works that deal with the distinctions drawn between human and animal or the practice of exclusion and inclusion in human identity, Dark Monologue takes as its starting point Franz Kafka’s monodrama A Report to an Academy. The story centers on an ape that has transformed into a human in a desperate attempt to escape his cage. In the story the ape is asked to explain his transformation in front of an audience of scientific scholars.

For the exhibition at Kinderhook & Caracas the story has been rewritten and transformed into a performance, where the ape narrator’s voice is split over three human mouths, set amidst sculptures, objects or “set-pieces”. These elements woven together, point back to the likes of an absurdist play that brings together research stemming from the science of current day primatology and the theoretical text The History of Animals by Oxana Timofeeva.

In Timofeeva’s words: “Philosophical systems supported by exclusion represent the animal as a being having another nature than the human. This fundamental distinction starts from the idea of exclusive human access to such things as logos, the good, truth or being.” However today primatologists like Frans De Waal have proven that this exclusivity is based on a continually crumbling border. According to De Waal, all human morality has its foundation in the two first pillars of morality: reciprocity and empathy. In a simple experiment where two Capuchin monkeys were given the task to exchange a stone for a piece of cabbage, it turned out the monkeys would refuse the exchange if they noticed they were being paid unfairly in relation to the other. Eventually both the “winning” monkey and the “losing” monkey would protest until rewarded equally. This experiment is just one of many that has changed the human understanding of animals. Yet in most cases when a human recognizes himself in the animal, he sees in the animal’s behavior only a kind of parody of his own gestures. But one could also ask, again quoting De Waal: “If we look straight and deep into a chimpanzee’s eyes, an intelligent self-assured personality looks back at us. If they are animals, what must we be?”