Artist: Cooper Jacoby

Exhibition title: The Living Substrate

Venue: Fitzpatrick Gallery, Paris, France

Date: June 5 – July 20, 2024

Photography: all images copyright and courtesy of the artist and Fitzpatrick Gallery, Paris

Sophisticated artificial intelligences will routinely tell you, when asked, that human intelligence is superior because it is located in a body. Well, they would say that. Still, it’s a nice thought to have, if it is, indeed, a thought. What type of advantage is it to have a body? To be at the mercy of hungers and hormones? To need sleep? To become irrational or emotional? To be finite, of course. To age and to die. But as AI reaches the outer limits of its own possible knowledge, it comes up against both corporeal knowledge and the evidence of human spirit that lives in art. AI needs bodies to produce more human content, otherwise it will begin to be trained on itself and spiral into its own model collapse. It also needs that difficult to quantify thing: the geist, the ghost found in the corners of our culture such as art and faith.

At present, an AI can only know a sculpture through the images, data, and language produced by humans. Humans, on the other hand, can know sculpture through the mouth. The mouth is where human infants first investigate the object world, and early comprehension of objects – texture, weight, durability, and volume – is oral. Though a human adult can assess an object with their eyes, and sometimes by touch where permitted, the vestiges of all this knowledge, the roots of it all, live in the mouth.

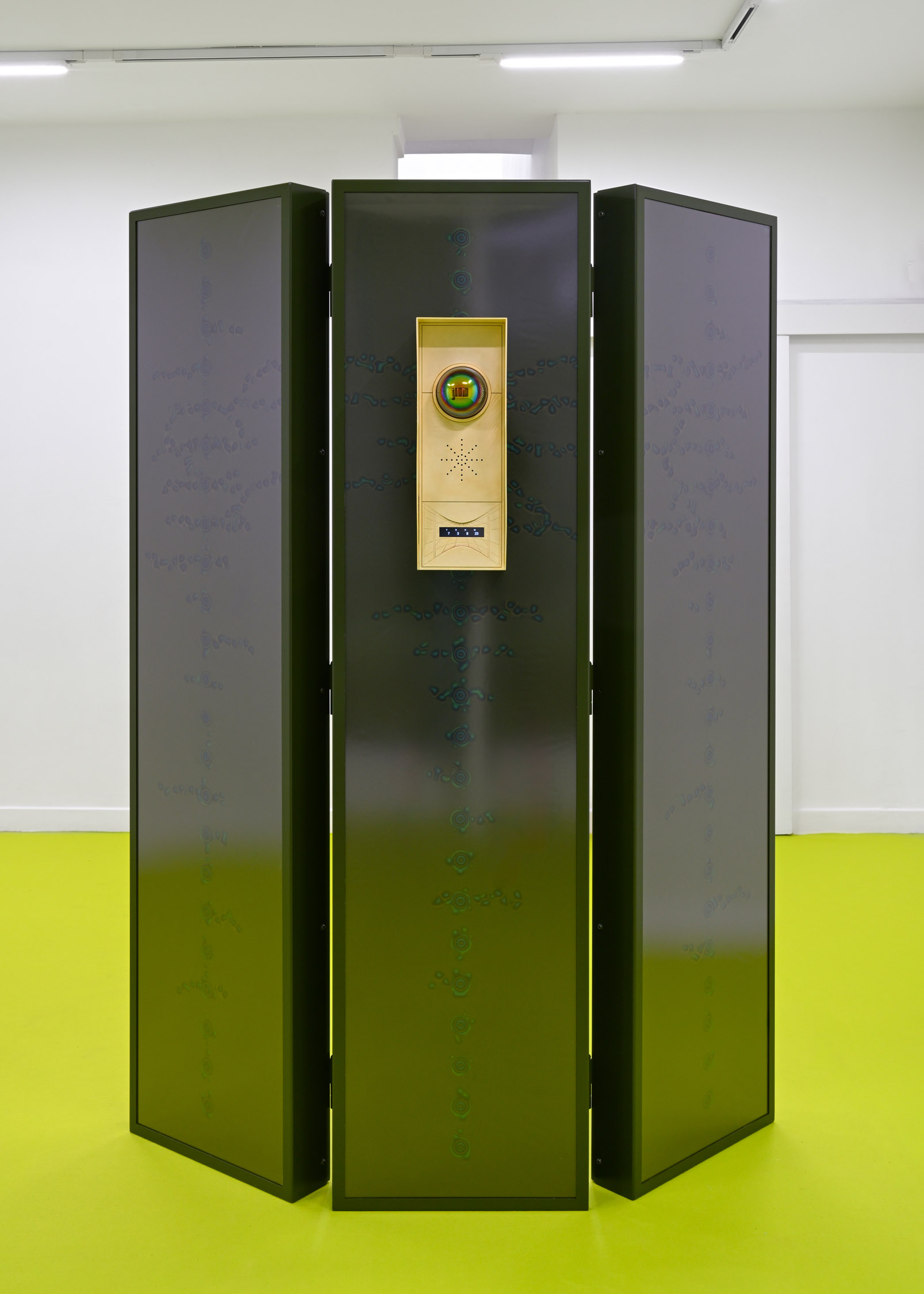

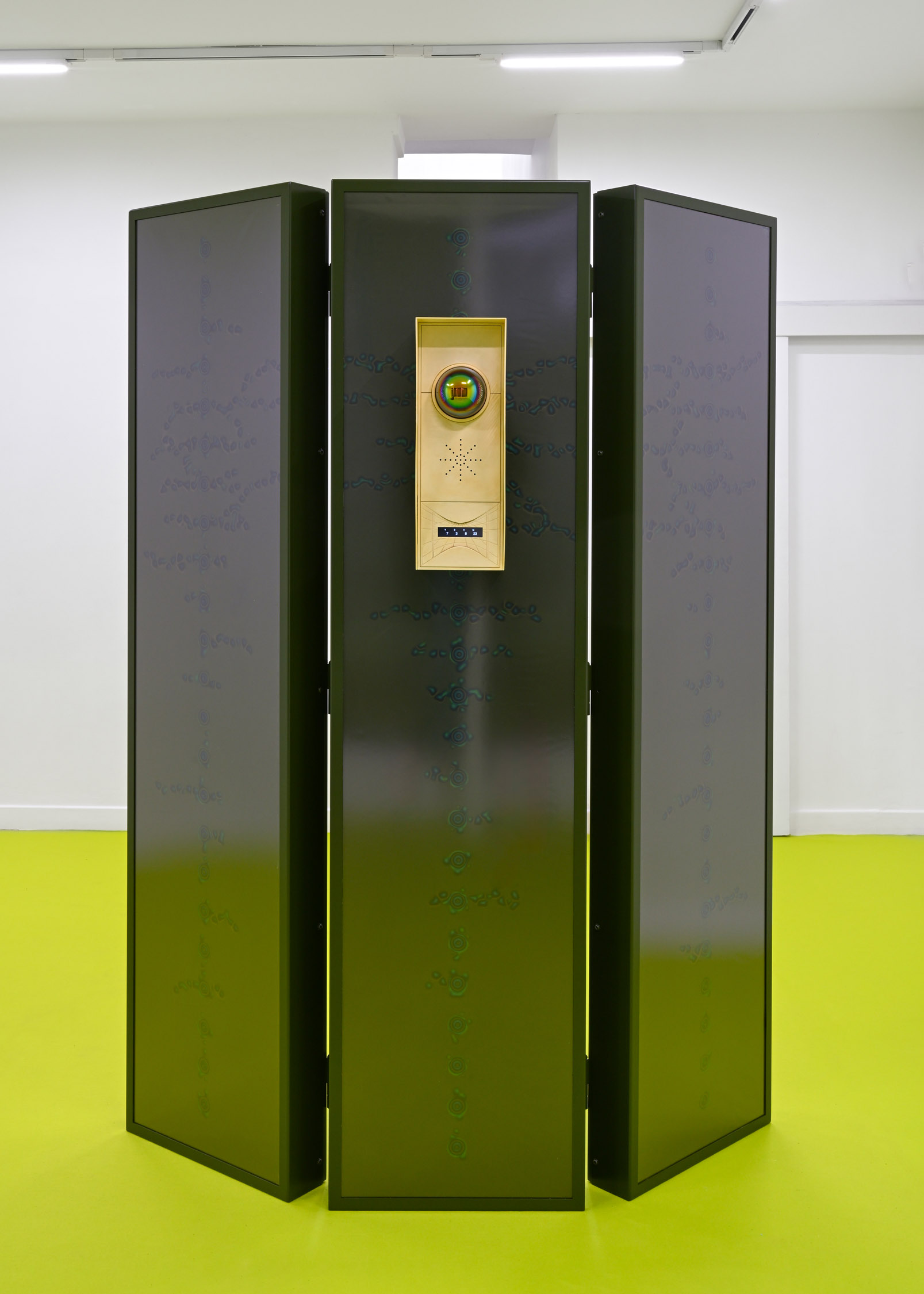

A form of human speech that has lost its mouth, lost its body, emanates from Cooper Jacoby’s sculptural series Estates (2024), deep-fried building intercoms that resemble old pieces of bone. The voices call out from inside a property to which we may be permitted access, while spherical surveillance cameras, like mirrored eyes, pan around, searching for identifiable bodies to address. The voices are based on the social media posts of a number of dead individuals from creative industries which Jacoby fed to GPT-2, an already-outdated language processing AI, which synthesizes the particularities of their posts to try and regenerate new phrases. These are voices without bodies, creatives without creativity, who call out at us from the undead internet. In this growing limbo, online debris made by the deceased now functions as free intellectual property to be scraped up and digested, a fertilizer for machine learning.

A crisis of interiority is inevitable when AI so closely mimics human speech, and when algorithms are programmed to guide our minds down selected pathways. The alphabet combination locks that keep the sculptural series Ruminators closed are automated to produce a language mimicking online engagement chatbots. These bots weaponize affect in a variety of ways – flirtatious, poor-me, kinky, sulky, angry – to provoke responses and hold human attention. “Pat my ass tell me it is ok”, says one of them, sweetly, before continuing “my mind is muck”. With texts that are wholly constructed from the combinations of nine letters, they are also machines for concrete poetry. Cast cow stomachs, with the unnervingly frilly flesh otherwise known as tripe, are also embedded into the exterior of the lockers. These physical metaphors for garbage and nonsense churn away in accompaniment, like the back end of a machine, digesting and processing the information that users leak away as they interact with engagement bait.

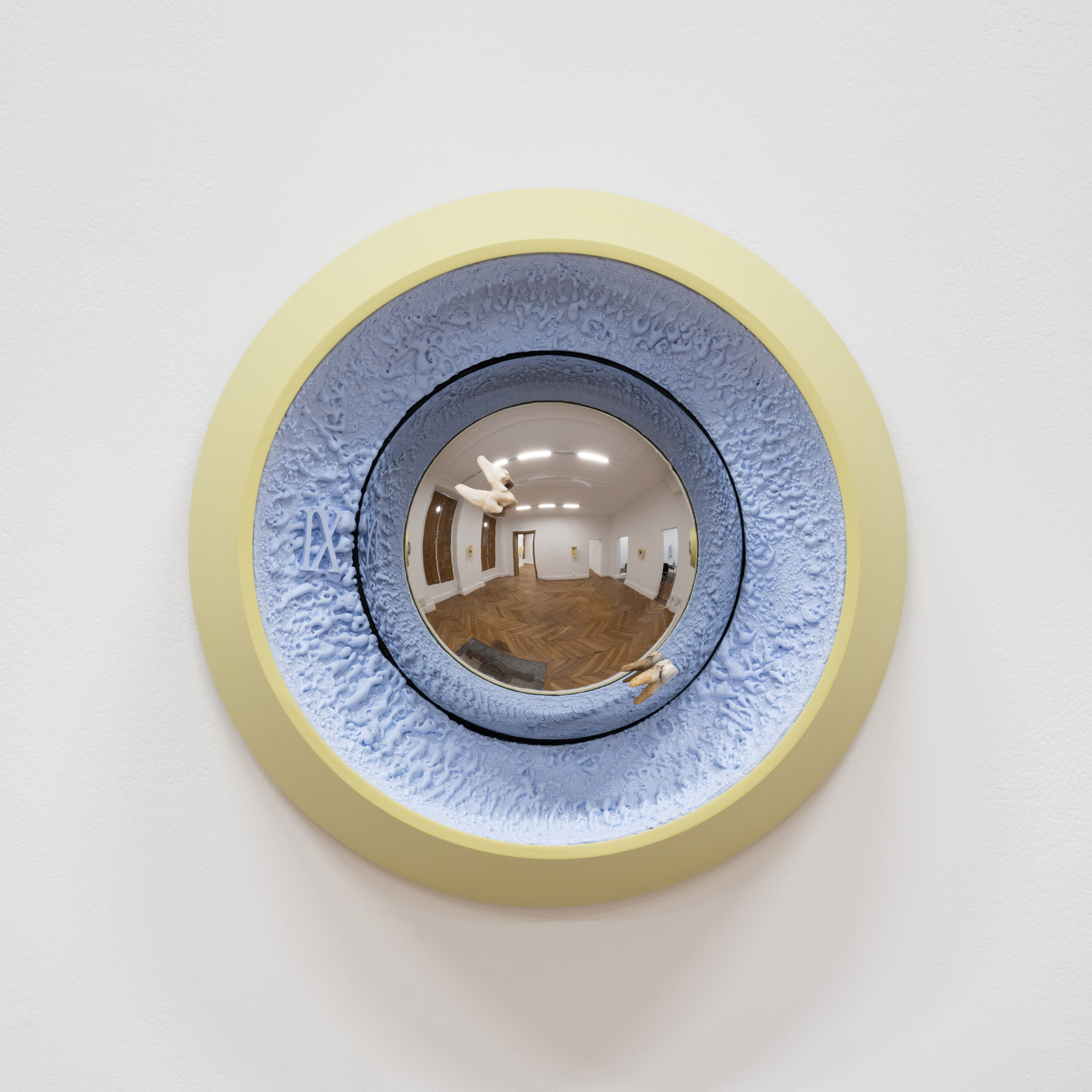

Teeth jump around clockfaces in a final group of works that link the subjectivity of time with the biological age of three living individuals. Some of us are ageing faster than others, including Jacoby, who, according to an epigenetic DNA test, has a biological age that is fractionally older than his calendar age. Part of a growing field of bodily datafication that includes pedometers and sleep monitors, these chronometric measures make bodies vulnerable to health and life insurance companies who can price human lives and widen existing inequities. The speed of each of these clocks with teeth ‘hands’ is accelerated or slowed to match the biological age of a person, so that a minute or an hour is shorter for those who are ageing faster than their bodies. Stress, lifestyle, genetics, and other environmental conditions make our bodies more vulnerable to time.

During our early oral explorations of the world teeth emerge: the mouth’s own tiny sculptures, quasi-alive. They have nerves and a blood supply, and without these they die. They also require the dull art of maintenance, and they cost a good deal of money to maintain in most of the world. Children put their teeth, those first little losses, under their pillows and hope for hard cash in exchange. Lesson learned. To me, teeth are one of the ultimate human subjects, existing at the threshold of almost everything: touch, finances, maintenance, mortality, corporeality, nerves, language, violence, food. And the teeth know the difference between what is alive and what is dead.

— Laura McLean-Ferris

Cooper Jacoby (b. 1989 in Princeton, New Jersey) lives and works in Miami, USA. He is currently enrolled in the Acadé-mie des beaux-arts x Cité internationale des arts residency. Recent solo exhibitions include Mirror Runs Mouth, High Art (Arles); Sun is bile, Fitzpatrick Gallery at The Intermission (Piraeus); Stragglers, Central Fine (Miami); Susceptibles, High Art (Arles); Disgorgers, Swiss Institute at LUMA Westbau (Zurich); Bait, Freedman Fitzpatrick (Los Angeles); Matte Wetter, 45cbm, Staatliche Kunsthalle Baden-Baden (Baden-Baden); Stagnants, Mathew (Berlin); Double Room #2 (with Rosa Aiello), KW Institute for Contemporary Art (Berlin); Deposit, High Art (Paris); Tradewinds (with Marina Pinsky), CLEARING (Brussels). The artist was part of group exhibitions at CAPC — Musée d’Art Contemporain (Bor-deaux); Hammer Museum (Los Angeles); CLEARING (Paris); Fondation Villa Datris (L‘Isle-sur-la-Sorgue); Le Plateau — Frac Île-de-France (Paris); Freedman Fitzpatrick (Paris); High Art (Paris); KM Temporaer at Neuer Aachener Kunst-verein (Aachen), amongst others.

Special thanks to: Domingo Castillo, Aric Grauke, Jürgen and Hildegard Findeisen, Laura McClean-Ferris, Shahryar Nashat, Leo Elia, Seth Rosetter, Stephanie Seidel, Joe Stewart, CA, HBB, ST, YS.