Artists: Ragna Bley, Magni Borgehed, Hi-5, Tom Humphreys, Mirak Jamal, Carl Mannov

Exhibition title: CONFLICTING EVIDENCE

Venue: 1857, Olso, Norway

Date: June 5 – August 16, 2015

Photography: images copyright and courtesy of the artists and 1857, Oslo

For “Omelette” 1857 moves into the territoire of painting at full throttle, and for once with the bulk of the artists sprung from the local scene. But what is left of the nnn when the nn is in exchange with the nnnnn?

Let’s just begin with a yawn. Come on now, a big yawn. Hhhhhhhhhhh.. (up up up) – (and descending): Aaaaaaahhhhhhhhh.. That’s it. Not to demonstrate boredom, oh no! but to prepare for this with some extra oxygen. To synchronize the tribe around the bonfire.

Now, didn’t that feel refreshing? Okay, here we go.

For its five-year-anniversary 1857 has put together a painting show for their grand summer spectacle. The gallerists have been thinking about this for some time. We last met at a masquerade in the southern hemisphere last January. Veiled behind a hare and a turtle mask they drunkenly exclaimed their long time desire to compile an exhibition sober in its loyalty to this chief category of art, and further elaborated on the enjoyable challenge of arranging it in the cool chill and day-lit diction of their concrete space. By far more welcoming in summer, the hare said. By far more welcoming in summer, the turtle said

The space is by far more welcoming in the summer. During winter it is as gloomy and rough as a Jack London campsite. And a challenging place for artworks of organic components all year round. A potential factor in a bonanza of Oil on Canvas, n’est-ce pas? The apparatus frequently seen in museums, the hydrothermograph, would be as superfluous there as a thermometer in hell. Not everyone would want to expose their paintings to such dire conditions? “Not slow-pacing tight-ass figurativists, that’s for sure”, one of them said to a common friend reluctant to take part. But never mind all this and let’s start outside.

●●●

It’s high noon and I’m standing on the sidewalk across the street. They’re expecting me now, but the sun pours down Tøyenbekken and I’m giving myself a few minutes méditatives to consider my expectations, ponder the gallery and its paratexts. For five years this mini-institution has produced some the most fresh and remarkable shows seen in this part of Europe, and gained well-deserved awe and attention in the art-zoo. Most of their fans and followers have never even been in the actual building, that’s for sure. So I’m stalling for a second to gain the most from my presence. Experience 1857 in its intégralité, so to speak. From face to behind, guts to brain.

Through the office windows I see the two guys in lively conversation constantly halted by short sessions of tapping on their laptops. They laugh a lot while performing silly gestures with their arms and heads. Naturally, I can’t hear what they discuss, but if I let my paranoia loose, the gestures c a n in some way be reminiscent of my own work, writing and ideology – translated into a comical act. A red bus roars past and a line of cars blocks my sight. When the window reappears they both eat ice cream and salute each other gaily with tiny espresso cups. An assistant enters with a bucket. She empties it in the sink before sitting down in the third chair, fatigued.

The ugly, little house, doing little to improve the view for the neighbours vis-à-vis, rises one more floor. From the rooftop a rusty iron facade stands as a wall, the only indicator of the large volume hidden in the back. It used to be a big, brown and bulky monochrome, subtle in its sobriety, but now it’s been the victim of, or the happy backdrop for, a graffiti piece and stands out like a white grin. As I step inside the guys pop up to shake my hand. The assistant is introduced and sets off to prepare another round of coffee.

●●●

The exhibition comprises five artists and an undefined collective. The selection is surprisingly local, and Scandinavian, in light of the gallerists’ proclaimed focus on international artists – whatever that means anyway. Swede Ragna Bley and Dane Carl Mannov are familiar names, as well as faces, on the Oslo scene, and both have already been extensively exhibited in the city. Previous principles regarding internationality and novelty seem to crumble, but perhaps 1857 has decided to finally put their own house in order. Magni Borgehed is another Swede, who lives and works in his native country, apparently far into the woods, while the British painter Tom Humphreys is the most established artist in the mix – in shrill contrast to the locally based Hi-5 collective, that though deliberately kept in the dark, I still deduce to have no insight, nor interest, in contemporary art whatsoever. Nevertheless they make their gallery début here. If Berlin based artist Mirak Jamal rings a bell, it might be because he curiously enough also was included in the last show at 1857, but with something quite different from what is on display now. — I was in Berlin a month back for the Gallery Weekend and the new series he presented in his studio was so damn good and fitting that we just had to throw it in there, Stian says with much enthusiasm.

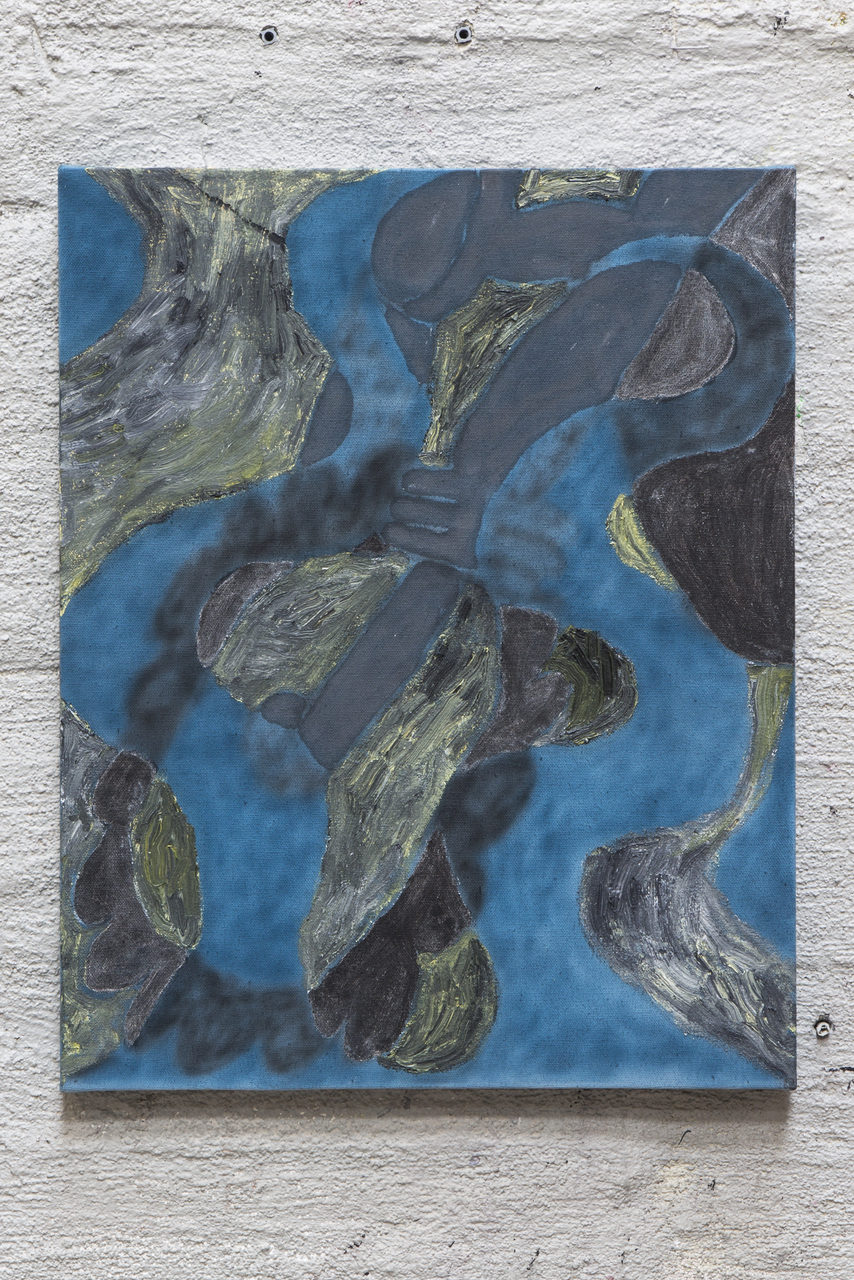

In the wacky antechamber with the orange floor Mannov, Borgehed and Jamal form an elegant and light-hearted trio. A group of paintings by Borgehed is what first catches the eye. The press release presents him as a Painter, with capital P, whose curiosity and playfulness give rise to, and thrive in, a constant outpouring. His dedication to painting is fundamentally an interest in the possibilities of applying and arranging paint on a canvas. The works have something generational to them, as if he is the heir and current practitioner in a long bloodline of craftsmen in the service of a radical modesty.

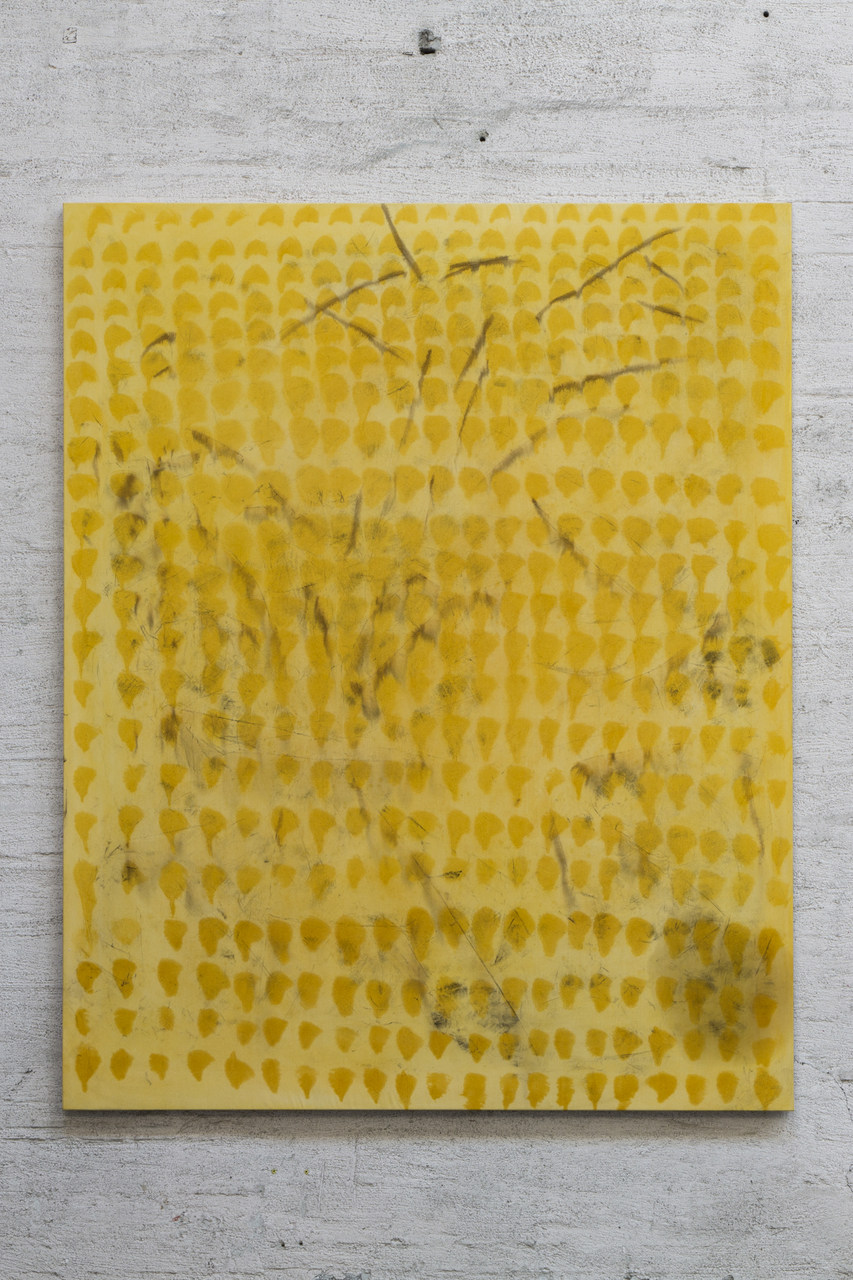

Throughout the show Mannov participates with a series of small works. His technique is more complex and styled than Borgehed’s. Or perhaps only more à la mode? On a smooth airbrushed background, added layers of strokes and figures shift place in variations of a motive that repeatedly maps out the front section of a motorcycle caught in a sea of wavy flames – commemorating and celebrating the times back in the 1990s when this space was the fortified siège social of the motorcycle gang The Outlaws.

Jamal offers only a teaser in the front space with a piece that in every way resembles painting, but has had its usual components replaced with other tools and materials. Nervous, machine-made scars and cuts together with engraved drawings create twitchy white inscriptions in a coloured plasterboard, sporadically decorated with spray-paint and prints. This ouverture is tight and agreeable. For once both color and jest goes well with the arrangements floraux, but I’m still thinking when are they going to get rid of that floor. — NEVER! Steffen exclaims and pushes me into the main space

●●●

— Let’s say that painting of the third millennium has evolved from Renaissance to Mannerism, Stian says ceremoniously, and gesticulates left and right, and I can’t make out if it’s an ironic joke or a personal belief. The works are scattered, even hung up high, out of reach. A perfectly square, freestanding wall suggests a division of the space. It is fully covered with a facsimile of a New Baroque tapestry from the 1870-80s, similar to fragments peaking up behind the drywall in the gallery. Standing upright alone it becomes a paravent chinois, flirtingly limiting full disclosure, tickling my desire to step around it. A jalousie. — Nope, more like an all-over pattern painting, they say. — Painting as decoration, they say. A vertical carpet too, they say. A painting is a vertical carpet. A poster too, they say, and tap twice on the wall with a skeletal finger. Corbusier said that a painting is a portable mural, Stian says. — Well, no, ‘tapestry’, Steffen says. — Tapestry, I mean, Stian says. Actually, he said ‘nomadic’, Steffen says. — Poor man’s portable painting, Stian says. — Mural, Steffen says. — Mural, Stian says. — The wall is also domesticating it? I say. — What? they say. — Well, this space, I say. — Well, sure, Steffen says. — But if painting as embellishment.., I begin. — Listen, they say. And then follows a rant, but their further elaboration of its purpose in this context is so back-breakingly confusing and contradictoire that I just let them talk themselves to the end while casting glances around. A monumental triptych by Bley displays soft rectangles, windows, enclosing abstract patterns, stretching from one canvas to the next, completed on a long stretch of cotton canvas, then cut up and stretched on stretchers. Not abstract enough to escape a Rorschach effect, but maybe, that is because I’m thirsty. They are a visually soothing, though palpitating, distraction to the tirade in the rumbling cathedral. Eventually dying out. — Right, I say. They exchange glances. — Any questions? Steffen asks. — Not right now, I say.

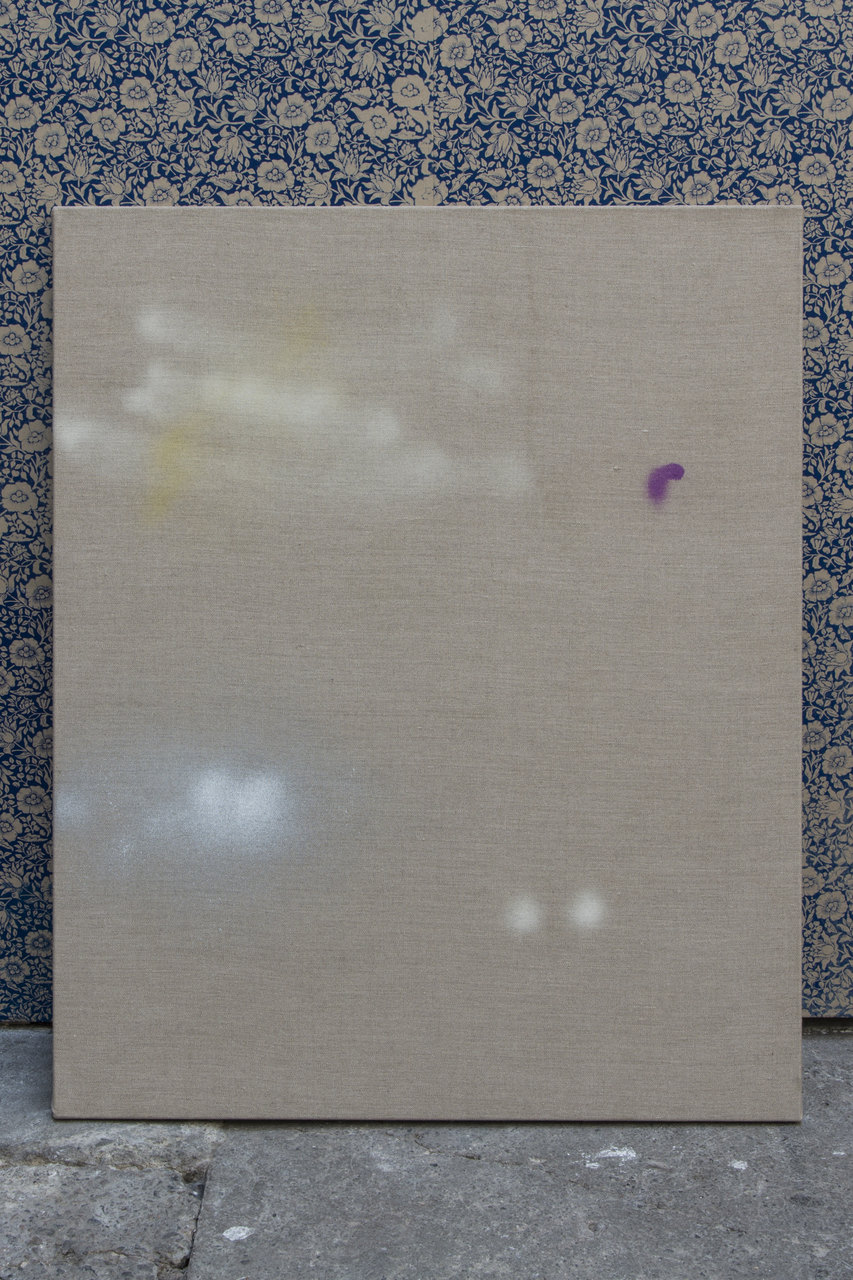

On the backside hangs a work by Hi-5. It is a medium-sized painting with a few dots, lines and twirls of spray on an untreated canvas. Technically realizable in one minute, a mope might say. I like it at first, but quickly feel it lacks intention, slightly confused by its indifference and simplicity. Awkwardly out of place on the tapestry background. Again, I inquire who or what, entre nous? The assistant enters with a tray of refreshments. The guys both reach for the same cake, their hands collide, coffee is spilled, and a Danish is knocked to the ground. I pick it up and consequently make it my choice. — We have to keep our sacred oath, Stian says, complacently nibbling at the bone of contention. — But come for the opening and see who seems alienated and out of place. And I am left wondering if this is just some cerebral practical joke. — It won’t be a farce if no-one tumbles over, Steffen says, doubly vexed. — Or hurts their head, Stian says, pointing to his head. I hold up my pâtisserie as a counterpoint. — It doesn’t have a soul, Steffen says.

●●●

I say that I think I’m alright now and prefer further contemplation en solitaire. — Absolutely, they say cheerfully, immediately striding back to the office and leaving me alone. Silence ensues. I lightly kick the wall and turn around with a flourish.

But lo’! More by Jamal combat the paravents sole protrusion into the volume. Full-sized sheets of green drywall take further calculated steps away from painterly conventions and, plops, enter my realm: l’espace! I walk up close, tilt my head, consider the epitome of a mustached man, scratched and cut.

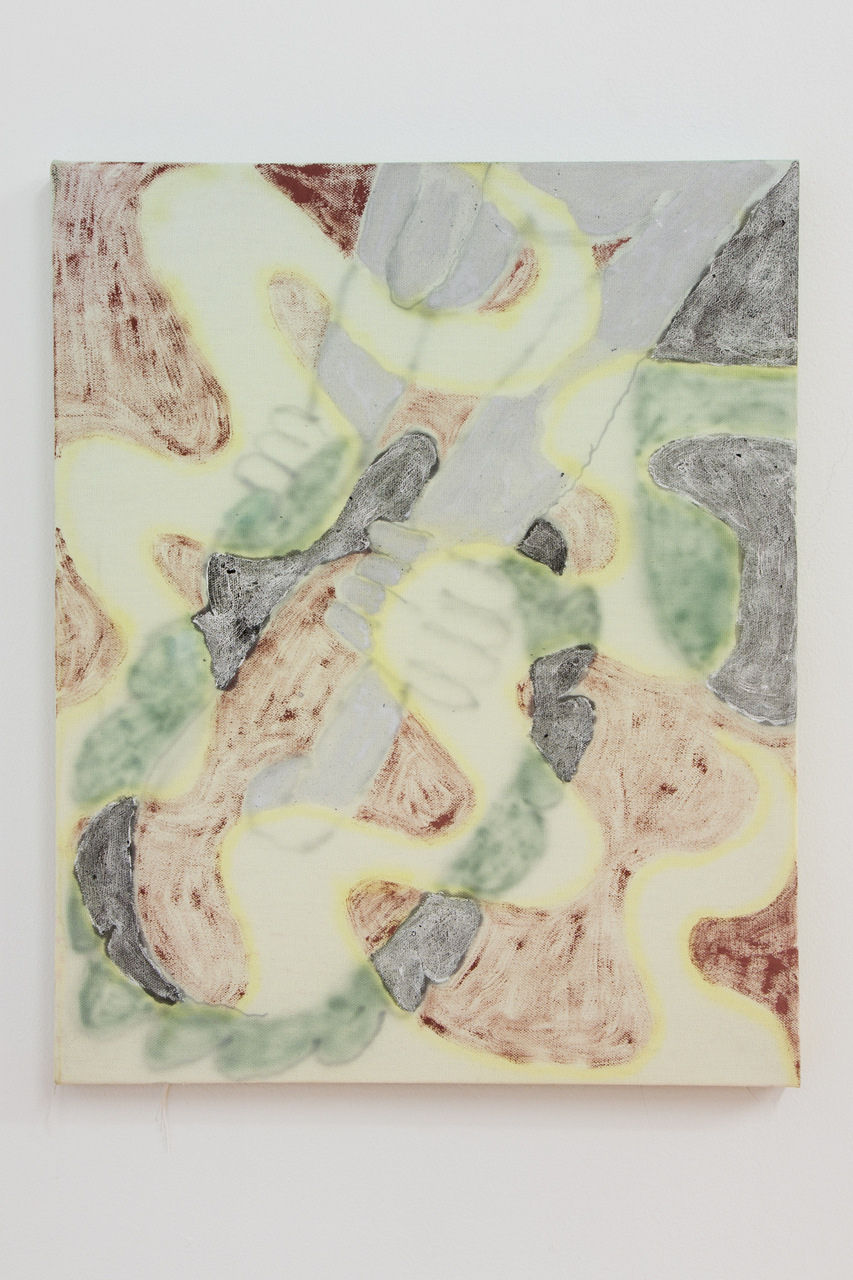

But behold! I observe the panels of Humphreys’ where they reside on the walls. A chorale of two. No brush has served them paint; no hand can reach them now. In this innermost salle I pace extravagantly from wall to wall, within flames and hallucinations and silhouettes both soft and sharp. The blue postered wall and its pimpled painting is surely mon souffleur. From my NN-A Astrup Fearnley tote bag I pull up the checklist and some leftover pop pops from the National Day, and I read the titles, memorize works, tick off names and celebrate with pangs of alarm, hurriedly lest my guides reappear to halt my delight.

It is a feast of paintings, and I am in its very midst. I hold up the victimized Danish like a skull in my hand, brushing off the concrete dust, and some crust and frosting too. — Oh, where be your wit now? I cry. — Where be your ridicule? Where be your excellent fancy? I softly touch its egg yolk lips. But the Danish lacks intention. And only replies: Eat me.

HI-5

Ragna Bley, Supporter in shade, 2015

Ragna Bley, One-size veil, 2015

Ragna Bley, It took a week to remember what I already know, 2015

Carl Mannov, Motorcycles and Flames (#3), 2015

Magni Borgehed, 2015

Tom Humphreys, Untitled, 2015

Carl Mannov, Motorcycles and Flames (#4), 2015

Tom Humphreys, Untitled, 2015

Hi-5

Hi-5

Mirak Jamal, My Father, pen on paper, Minsk USSR, 1985, 2015

Mirak Jamal, My Father, pen on paper, Minsk USSR, 1985, 2015

Magni Borgehed, 2015

Mirak Jamal, Still Life, pen on paper, Minsk USSR, 1985, 2015

Mirak Jamal, Landscape, pen on paper, Minsk USSR, 1985, 2015

Carl Mannov, Motorcycles and flames (#1), 2015