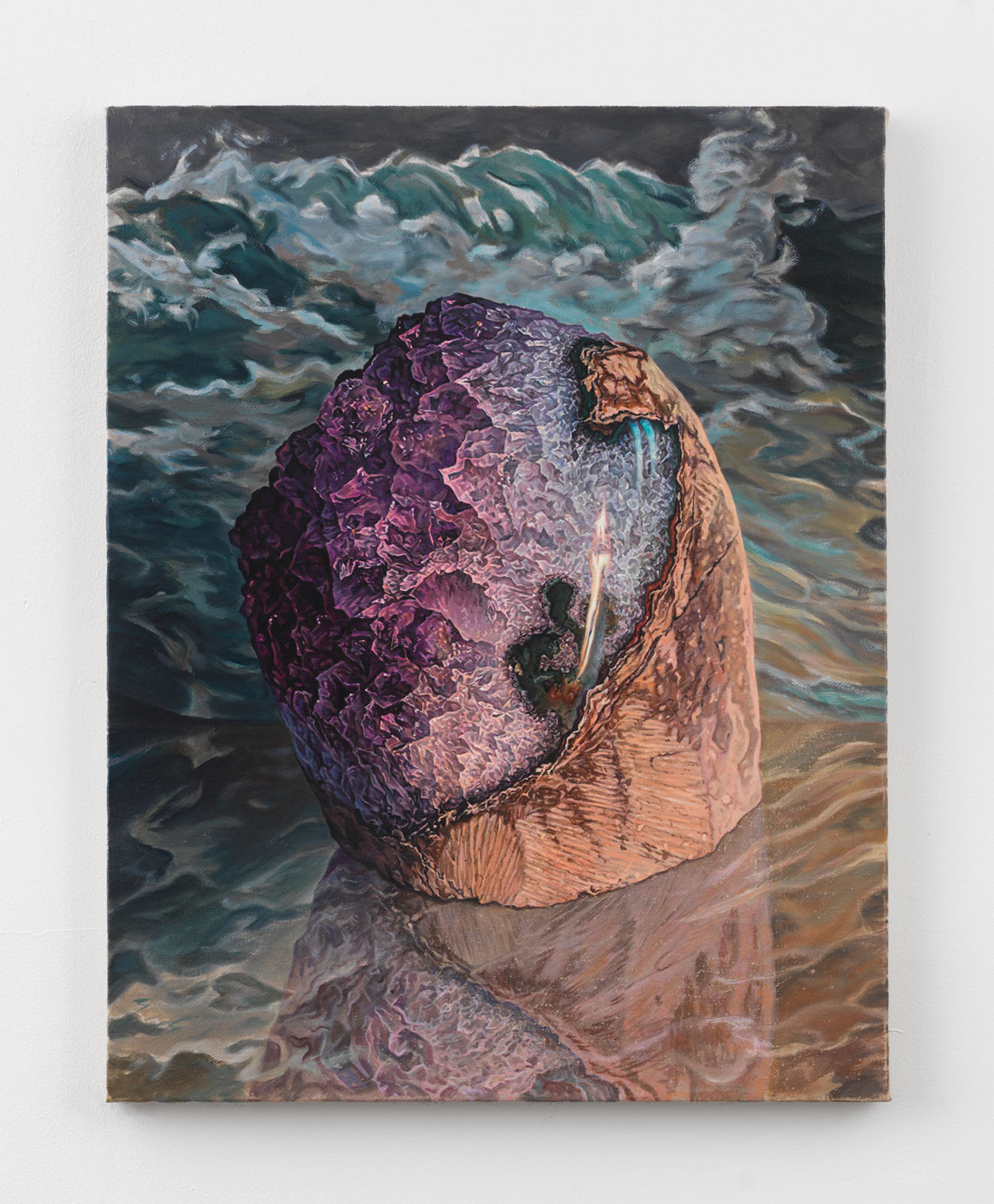

To speak of geodes and crystals is, for some, to evoke souvenir shops and the scent of incense– yet this association forms only one, miniscule point on a timeline which stretches further than human comprehension. Take amethyst, the quartz whose spiritual symbolism espouses inner peace and clarity, but whose violet luminosity is formed in volcanic rock geodes over millions of years. Crystals offer a distillation of humanity’s relationship to temporality; their cultural meaning is markedly contemporary while their geological origins stretch deep into history. It is these contradictions and complexities of time which fascinate the California-born, New-York based artist Chason Matthams.

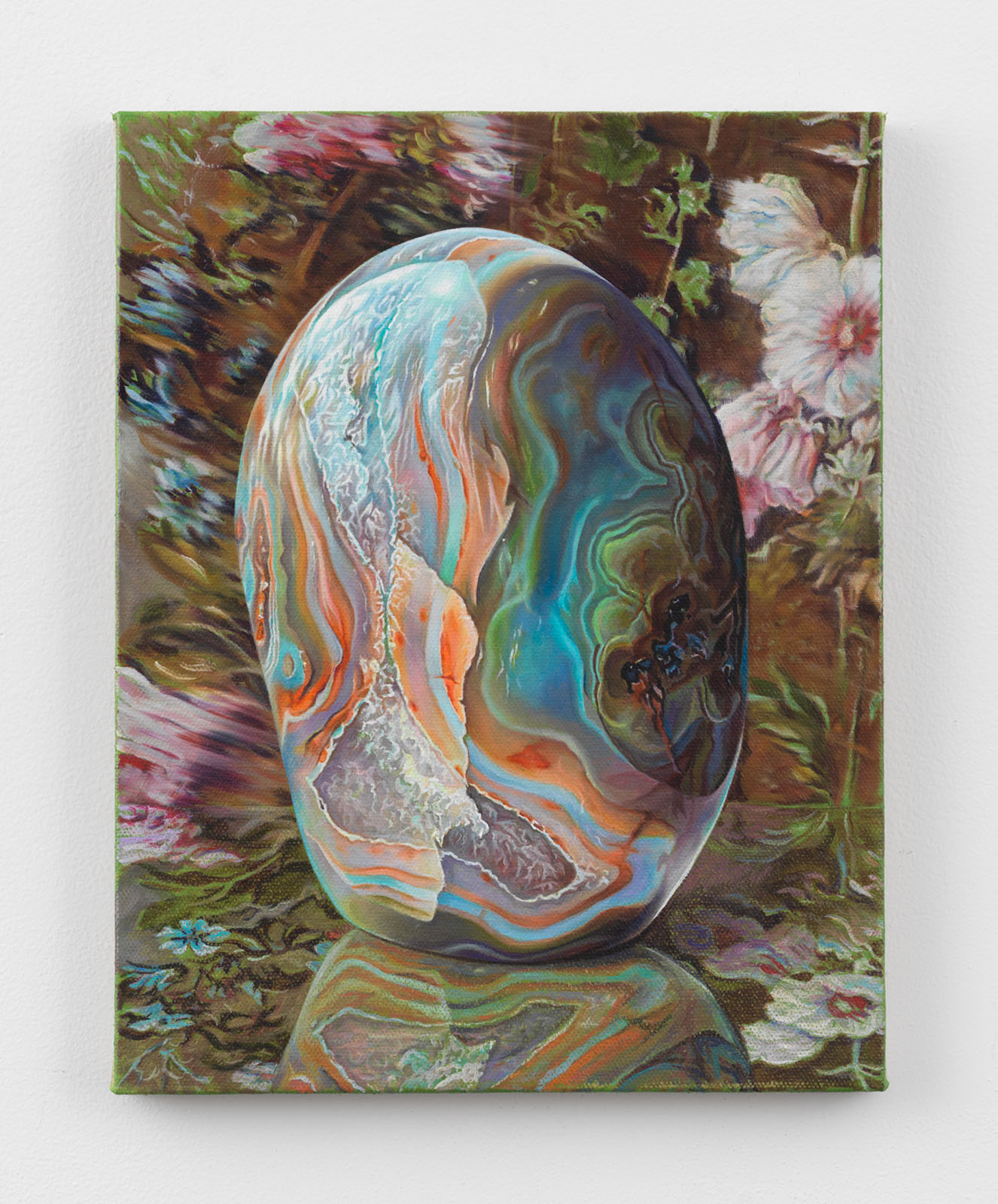

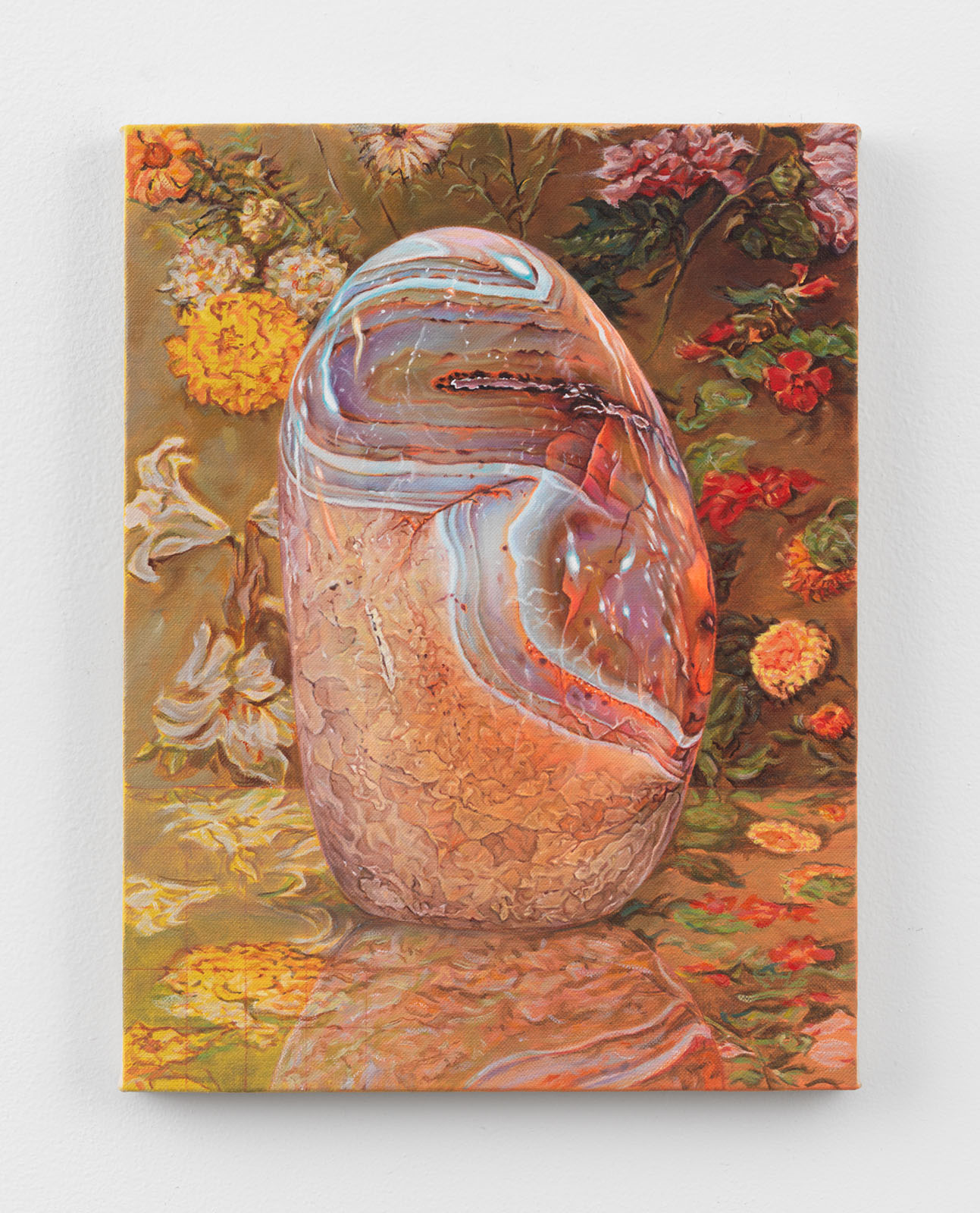

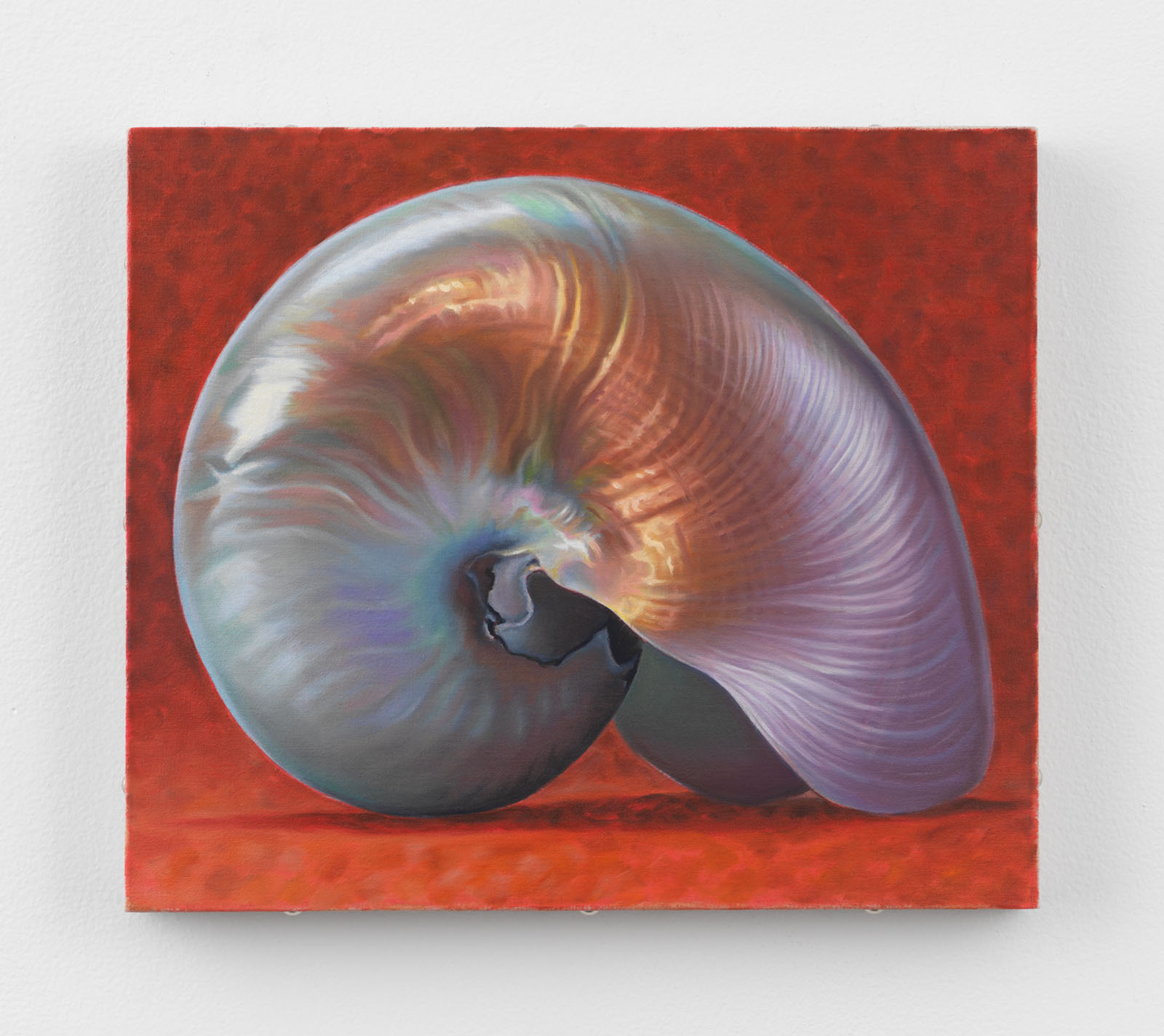

Matthams’s practice is characterised by two major areas of subject matter: his studies of vintage and contemporary film cameras, as well as organic forms such as shells and stones, which foreground backdrops drawn from art historical sources and self-arranged corsages of flowers. The former turn the act of representation back on itself: by depicting the machinery with which images are frozen and time is stilled, the artist nods towards the history of seeing and depicting itself. These technologies of image have both enabled us to witness the passage of time– through the likes of microscopy, aerial views and the time-lapse– and they have also endowed us with the power to label and categorise it.

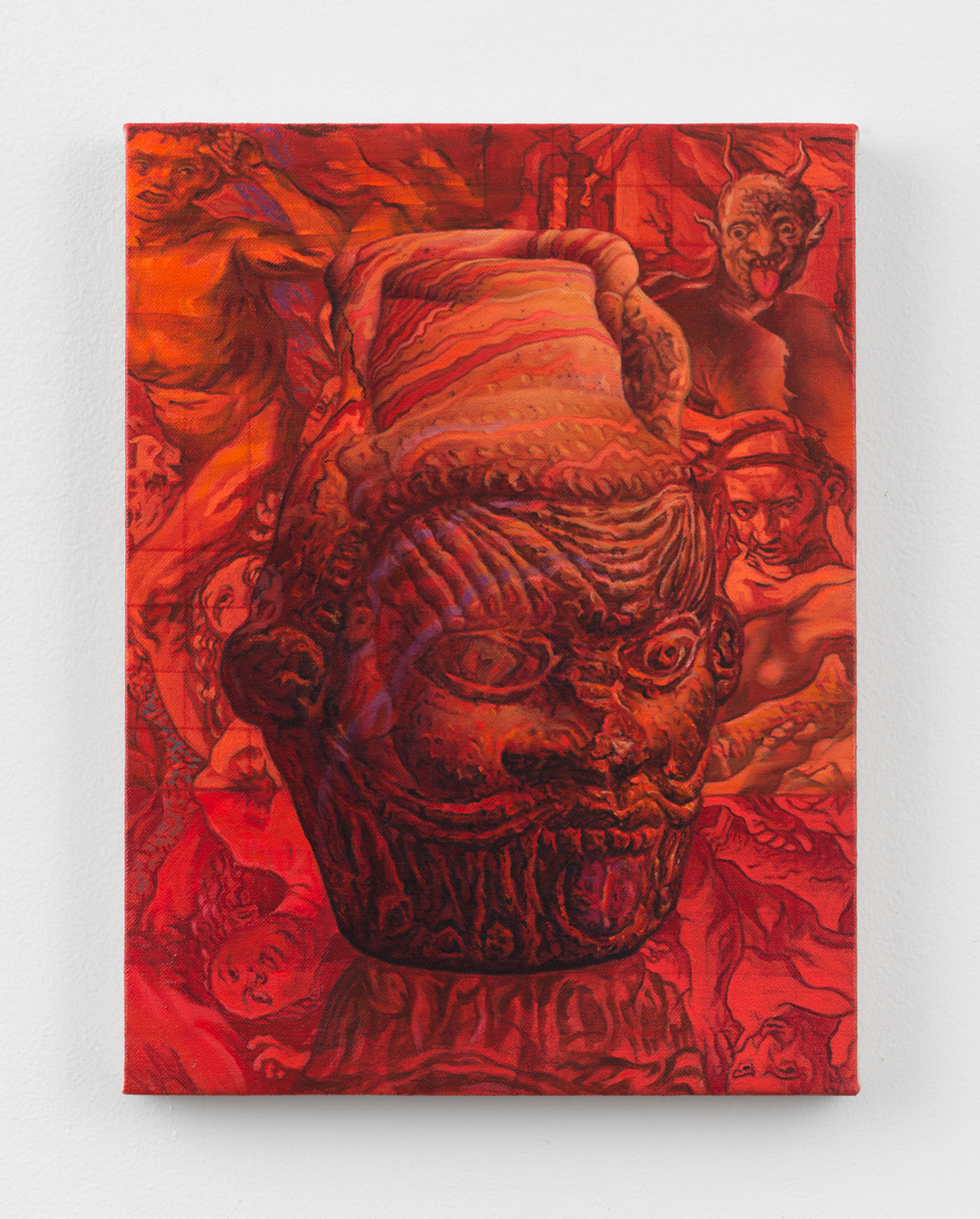

Though Matthams nods to these practices of classification in the literal titles of his works (the most notably of which is Tridacna Shell w/ Adrien van der Spelt’s Trompe-l’Oeil Still Life with a Flower Garland and a Curtain, 2025), his compositions themselves evade a sense of finality. This instability of meaning is further replicated in images such as An Egyptian Mug w/ Jan Sanders van Hemessen amalgamation, 2025, which depicts neither camera nor entirely natural form. Instead, here Matthams explores the ways in which cultures bleed into and across each other. The atmosphere of this reddish painting is more foreboding than the rest– our unstable identities, after all, are not always (perhaps not ever) devoid of violence and tension.

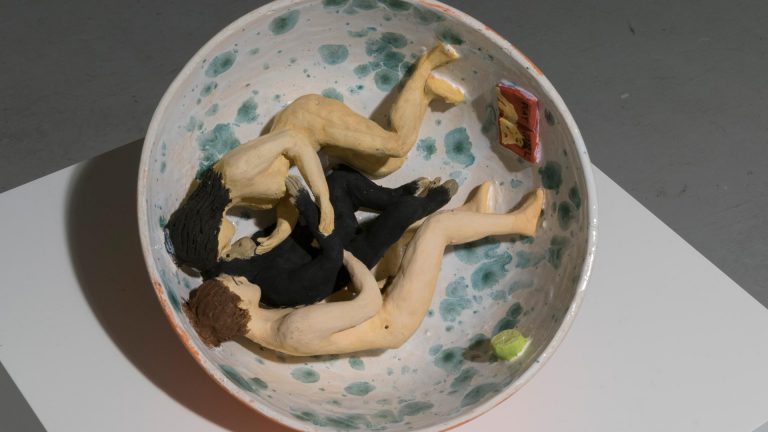

These paintings, however, do not shy away from the multifaceted histories of meaning. They acknowledge the complexities inherent in a shop-bought lapis lazuli versus a pigment which is mixed into the historic paintings they reference, and the ancient stone it derives from. They defy the boundaries of artificial and natural which have tended to structure Western history, instead blurring the two. In a recent interview, Matthams quotes a Phil Elverum lyric: “I told a fish, what you see as a palace, is running water. The fish said, no, what you see as those mountains is flowing matter… And after our talk I saw the wall of rock as a wave in the middle of breaking”. In other words, what might appear to us as fixed and solid now, is in reality liquid and uncontainable. It is futile to think, as humans have done for so many centuries, that we might ever be able to truly capture this ever-changing world.