Artist: Cecilia Vicuña

Exhibition title: Cecilia Vicuña. Seehearing the Enlightened Failure

Curated by: Miguel A. López

Venue: CA2M Centro de Arte dos de Mayo, Madrid, Spain

Date: February 20 – July 11, 2020

Photography: Roberto Ruiz/ all images copyright and courtesy of the artist, CA2M Centro de Arte dos de Mayo and the respective copyright holders

Cecilia Vicuña. Seehearing the Enlightened Failure, presented jointly by Kunstinstituut Melly, Rotterdam, and CA2M – Centro de Arte Dos de Mayo – is the first retrospective of this Chilean artist’s work to be held in Spain.

The foremost exponent of Latin American art on the inter-national scene, Vicuña has long been considered to be a leading performance artist, but she is also a writer, poet, activist and visual artist.

She was distinguished with the Spanish art award Premio Velázquez de Artes Plásticas 2019 for her outstanding work and her multi-dimensional art, distinguishing her as one of the essential figures in contemporary Latin American art.

Since the 1960s, Cecilia Vicuña (Santiago, 1948) has been offering a radical view of the relationship between art and politics through her writing, and through her artistic creation. She worked in different parts of the world after leaving her native Chile for London in 1972, eventually settling in the United States in 1980.

For decades, this poet, visual artist and activist has been forging a varied and multi-disciplinary body of work, built using words, images, environments and a combination of languages, media and techniques.

The exhibition, curated by the Peruvian Miguel A. López, brings together more than one hundred works – shown for the first time in Spain – reflecting the artist’s ongoing commitment to themes ranging from eroticism, colonial legacies, the struggle for liberation, collective joy, indigenous thought and environmental destruction.

Starting with words, she constructs huge installations and paintings that draw from certain indigenous languages while also focusing on her relationship with nature and feminism. She also compiles different types of documentation that narrate part of her journey, making her work timelessly radical.

The military coup that took place in Chile in 1973 had a profound effect on Cecilia Vicuña (Santiago, 1948), shaping the structure of her emotions in her formative years, and that of the entire nation. Her work is linked to political resistance, and feminist and sociological precepts, dialogues with indigenous culture and environmental justice permeate her work.

The curator, Miguel A. López, highlights Vicuña’s convictions in his interpretation, selection and presentation of her art, whose function is not to colonise or dominate, but to foster change in social and emotional structures: ‘Her desire to dignify rubble, the tiny fragments and the things we throw away, focuses the question on how to reconnect the scattered parts of what we might today call ecological justice – an assembly of many worlds and multiple forms of awareness.’

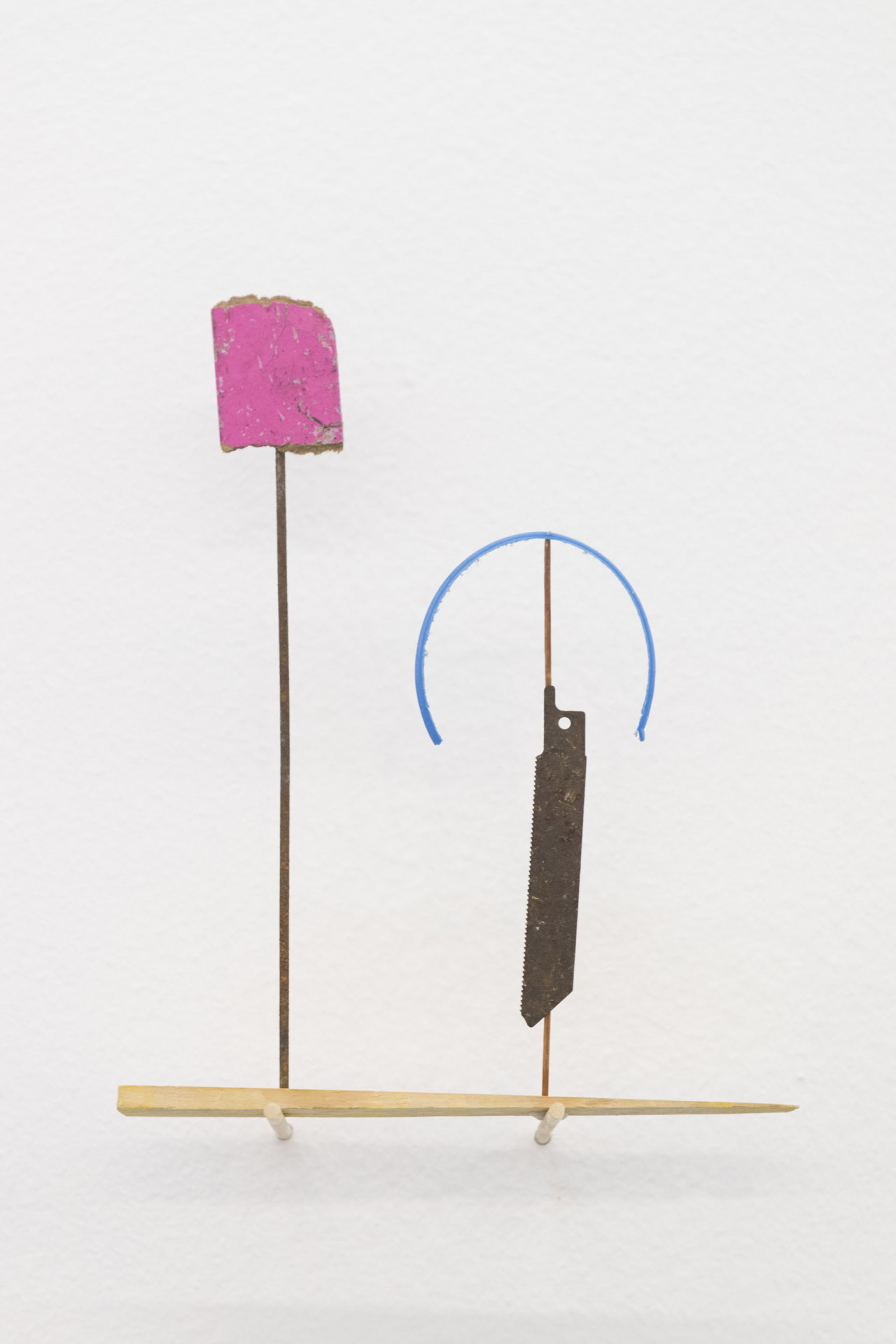

Her first assemblages, produced in 1966, were swept away by the waves and the sea breeze. Unlike international movements such as land art or participatory art, her early work was not a response to debates about modernism, institutionalism, the market, or even art itself. Her pieces were not early exercises in minimalist art or ‘sculptures in the expanded field’ – both of which were subjected to a rapid process of institutionalisation between the 1960s and 1970s in the United States and Europe. The artist created small assemblages out of items collected from the beach: she placed them on the shore in a humble act of communication with nature. Like sacred offerings, these fragile material articulations – made of driftwood, pebbles, feathers and string – took part in a larger dialogue. She called them precarios [the Spanish word meaning ‘precarious’], but also spatial metaphors or multi-dimensional poems. Using found materials – what she calls basuritas [bits of refuse] – is a way of highlighting the possibility of unearthing the meanings and strengths of things that are destined to be disposable by the frenzied logic of consumerism and the quest for profit. The delicacy, ethereal quality and small-ness of these pieces are integral aspects of her work, even though this ephemerality has often meant that the importance of their significance has hardly been acknowledged.

Andean peoples would weave meanings into textiles and knotted cords. The quipu is a ‘writing’ system using knots made on coloured cords that was invented in the Andes over 5,000 years ago, meaning that it may be older than writing. The quipu had a virtual counterpart, the ceqe, which means ‘line’ in the Quechua language. It was a concept that connected all communities to sacred sites on the earth, usually where there was water. Vicuña began tying quipu knots when she was a teenager living in Chile. It was still being used at the time of the Spanish conquest of South America in the 15th century but was banned shortly thereafter.

For her, therefore, it was an act of rebellion to once again begin the process of speaking through the cords. The quipu is made of unspun wool that symbolises the state of ‘not-yet-being’ from which everything is born. When people pass through it, they themselves become the ‘knots’, the bearers of memory. A poem in space, a way of remembering, involving the body and the cosmos at the same time. A tactile and spatial metaphor for the union of everything.

Vicuña values the ritual, medicinal, healing or shamanic dimension of art, whose function is not to colonise or possess, but to bring about modifications in both microscopic structures (non-visible phenomena) and macroscopic structures (perceptible physical experiences). Her cyclical understanding of the creative act is expressed through a return to ideas that do not exist as ‘final objects’, but as rehearsals – like the precarios and quipus that she has been creating since 1966. Her weavings and assemblages seem to recall the memory of ancient civilisations. The hair, strings and plant and mineral debris the artist incorporates into her work evoke indigenous settlements, Andean wak’as (sanctuaries, idols, temples and tombs) and the remains of native peoples that reveal aspects of indigenous ontologies and other ideas of the sacred that challenge Western notions of time – in Andean philosophy, past and present are part of the same non-evolutionary and non-determinist temporal concept based on convolutions or loops called pacha.

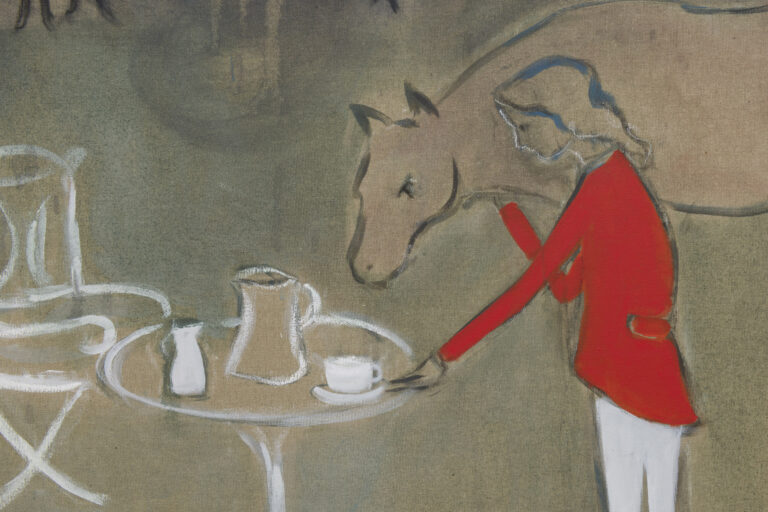

Cecilia Vicuña began painting in the mid-1960s. She was influenced by Andean and mestizo painting produced by the Cuzco School in the 16th and 17th centuries, which appropriated iconographic elements of European art in order to preserve Andean beliefs. Her encounter with the painter Leonora Carrington in Mexico in 1969 was also significant. Drawing on these influences, Vicuña’s paintings included nude women protesting in the streets, references to animism, Andean philosophy, folklore and popular myths, as well as depictions of important left-wing figures and feminist and civil rights activists. It was a continuation of colonial images of saints painted by mestizos – a Spanish tradition with a Latin American twist – that offered a glimpse into the syncretic Latin American culture of today. Although such works were exhibited in museums and nationally acknowledged, they also proved to be controversial, such as Ángel de la menstruación [Angel of Menstruation] (1973).

The sexual drive of her early poems – such as Retrato físico [Physical Portrait] (1966), Anatomía del papel [Anatomy of Paper] (1967), Luminosidad de los orificios [The Brilliance of Orifices] (1968), among others – challenged the patriarchal dominance of cultural norms.

In September 1967, Vicuña wrote No-manifiesto [Non-Mani-festo]. This document gave rise to Tribu No, a collective of young poets and artists in Santiago who, like Vicuña, sought to visually express their opposition to the country’s conservative forces. Tribu No’s improvised actions were influenced by self-reflexive experiments in the field of poetry. Tribu No was an expression of liberation and collective joy. Between 1967 and 1972, they created poems, drawings and pain-tings, as well as rituals, games and physical improvisations. Several black-and-white photographs taken between 1969 and 1970 show three women – Vicuña and her friends Carmen Bertoni and Coca Roccatagliata – dressed in black and lying on the floor, their bodies entwined. In another photograph, Sonia Jara and Roccatagliata appear naked in an embrace, surrounded by plants and flowers, as if listening to the sound of their bodies.

After moving to London in 1972 on a scholarship to study painting, and shocked by the brutal coup engineered by General Augusto Pinochet on 11 September 1973, Vicuña distanced herself from her vivid and exuberant paintings of harmony between animals and humans and of triumphant liberation movements. Her work took another course, one of agitation and mourning. ‘Allende’s death marked the end of my life as a painter,’ she concluded. La Ruca [a term used to describe an indigenous dwelling found in the Pampas and Patagonia regions] is an anticipatory work of art which, like Biombo [Screen], puts the viewer in the centre of the piece in order to redirect their view; in this case, they are invited to look through Allende’s eyes and his trademark dark-rimmed glasses.

The cheap reed blinds forming the windows of the installation echo the forms of improvised and nomadic architecture, often erected by women; typically, transportable structures made of sticks tied together. Plants, wooden dowels and branches are tied together to support some of her previously completed paintings (a sort of alternative gallery), while a large portrait of Allende with his eyes cut out hangs on the outside. The fluttering cloths above the little house evoke the Chilean tradition of planting a red flag after the roof of a house has been built, signalling the arrival of its new occupants.

In another collective effort, Cecilia Vicuña, David Medalla, John Dugger and Guy Brett founded Artists for Democracy in London in 1974. This group mobilised international artists and intellectuals, who responded to their call to donate and create works in support of Chile’s struggle to restore demo-cracy. Their contributions ranged from a mass demonstration in Trafalgar Square to collages and paintings demanding an end to imperialism and colonial rule.

In 1977, Vicuña presented Homenaje a Vietnam [Homage to Vietnam] in Bogotá. It was an exhibition celebrating the victory of the Vietnamese people. Her paintings highlighted the beauty of the renewed relationship between bodies and the natural world in a reunified Vietnam. The works, painted like banners of silk, cotton and strips of cloth, were hung on bamboo poles. Vicuña’s intention was for the wind to flow through the works in the same way that the fight flows through the air.

One of her most important paintings is Chile Salutes Vietnam! (1975). This work shows an indigenous Mapuche woman and a female Vietnamese guerrilla fighter in a lush landscape of plants and flowers, exchanging a rifle and a red book entitled La revolución de agosto [The August Revolution] – the name of the Vietnamese revolutionary uprising against the French colonial government in 1945. The image documents a transfer of knowledge about anti-colonial war and suggests both an intellectual and military connection between Vietnam and Chile at a time when Latin America’s military dictatorships were setting in motion a machine for persecution, torture and death known as Operation Condor. That US-backed campaign of political repression was an organised system of state-sponsored terrorism.

Since 1973, this artist has been creating collages and drawings and undertaking actions as part of her Palabrarmas [Wordweapons] series. Largely created between London and Bogotá, Palabrarmas express unresolved paradoxes between art and revolutionary politics. Through the representation of words as weapons, the series advocates the transformative dimension of language in the fight against dictatorships. Palabrarmas are words that have been opened up to explore their possible meanings, revealing a space for the development of imagination and trans-formation. This notion of openness is emphasised through the image of the ‘shovel’ that stirs up language as if it were soil in order to ‘till’ it, with the dual meaning of both working it and cultivating it.

Through words, what may seem fixed in language is set in motion and words are rewritten, spreading them out beyond the limits of syntax and their usual meanings. Just as the work of art is relational, sustained by the action of many agents, the word is understood by Vicuña as a multiple and spirited entity in transformation, always in relation. Palabrarmas are not isolated and discreet objects; rather, they reveal how a word that apparently designates a single thing leads to a web of other words, knowledge and beings, as if it were a strand of a much wider and denser fabric. The emphasis placed on the creative act also had a compelling political connotation for Vicuña. As the termination –armas [weapons] suggests, palabrarmas were intended to be instruments of war with which to oppose the brutal aggressions of military dictatorship. The first palabrarmas Vicuña coined in London in 1974 were ‘verdad, mentira and sol y dar y dad [playing on the Spanish words for ‘truth’, ‘lie’ and ‘solidarity’, respectively]. Vicuña’s palabrarmas of the mentira [lie] are conceived as the atrocious violence used to slash bodies into pieces; while the word verdad [truth] is transformed into open and outstretched palms as a gesture of humble and simple offering. Vicuña contrasted the watchful and repressive prison regime imposed by the dictatorship with acts of openness expressed as a hand that welcomes, holds, receives and delivers a vision, a word, a call.

In 1975, Vicuña returned to Latin America and settled in Bogotá, where, in addition to her participation in political meetings of the Chilean resistance in exile and research into Maya codices and the vernacular art of the Americas, her most rewarding working experiences were her collabo-rations with music and theatre groups, such as the Corporación Colombiana de Teatro, for which she painted stage sets in 1975 and 1976, and with the Chilean folk music group Quilapayún. In addition, she held workshops in collaboration with indigenous communities such as the ones she held in 1979 for the Guambianos, an indigenous community in the Valle del Cauca region of southern Colombia. During those years, she travelled around the country on her own, giving talks on the Chilean struggle and offering poetry readings. Also in Bogotá, she gave street performances, including a 16mm film based on interviews with prostitutes, policemen, beggars, activists and slum dwellers that was called ¿Qué es para usted la poesía? [What is Poetry for You?] (1980).

Until relatively recently, Vicuña’s work was not included in the narratives on artistic practices that challenged the military dictatorship in Chile (1973–1990). Her work was not included within the Escena de Avanzada [Advanced Scene], the term coined by the theorist Nelly Richard in 1981 to refer to the anti-dictatorship art that emerged between 1975 and 1982, mainly in the fields of graphic art, performance art and conceptual art. Vicuña’s work was also excluded from all other accounts of critical art produced in the 1970s and 1980s, years in which she was living and working in exile. In hindsight, it is possible to see how her ignored work did not fit into – or interrupted – the listings and conceptual models used to identify political art practices under Pino-chet’s dictatorship.

Vicuña’s desire to dignify rubble, the tiny fragments and the things we throw away, focuses the question on how to reconnect the scattered parts of what we might today call ecological justice – an assembly of many worlds and multiple forms of awareness. In that awareness lies the poetics of enlightened failure, the possibility that the ordinary can become an event. In this sense, the fate of much of her work underscores disappearance as the thing that generates the entirety of her poetics. Her poetry-actions, her precarios, her spatial metaphors, her collages and art hangings, her songs and her living quipus, insist that there are no successions, only returns.