“The name does not cease to be a revealer of the essence of things because it resembles them.”

Julia KRISTEVA, El lenguaje, ese desconocido, 1969

“I can’t turn around

It’s too late

You can call my name”

Jimmy SOMMERVILLE, It’s Still Hurts, 2004

How can we know when names have lost their power? The voice, which can also become a tool of domination and violence, does not need a solid space in which to leave its mark, it can subjugate something more flexible, it can even be inscribed on a body, configure an identity.

Many stories begin like this, with the exercise of naming, something simple that reveals a strategy of submission and belonging. We are possessed by the one who has named us, we must pay attention to our names, those that throughout our life have been assigned to us, discovering parts of us that we may not even know.

“I’ve been sick and I’m perverse

Oh, I’m hideous

If I’ve had you at your worst, it was easy in return

Oh, I’m hideous”

Oliver SIM, Hideous, 2022

“What I didn’t know yet was that insults and fear were going to save me from you, from the people, from the ideological reproduction of your life. I didn’t know yet that humiliation would force me to freedom. Not a day went by without me thinking, I have to go, I have to go; that phrase had become a part of me.”

Édouard LOUIS, Changer: Méthode, 2021

In 2004, the English translation of Didier Eribon’s Réflexions sur la question gay (1999) is published. The first thing that draws attention in this edition is the change in the title of the book, leaving aside the homage to Sartre in the original title and prioritizing the content of the first chapter. Its new name: Insult and the Making of the Gay Self.

As Eribon points out, insult can appear even before one’s own identity; this attack can precede the discovery of the individual’s emotions and desires. The act of being discovered by others before oneself, and that this discovery is assimilated with violence and negativity, will first generate in the individual a rejection of his own identity. If my self is an element that serves to harm me, I prefer to do without that self and assimilate my personality to the environment.

Many non-normative affectivities are built from this denial, trying to negotiate with the environment while giving up parts of oneself; the construction of this person may be “successful” by allowing one to live in denial and conflict, on other occasions the performance of this body that is attempted to be modeled through violence – verbal and/or physical – will not allow the masquerade; it is also possible that it does not desire it.

The chapter of Eribon that follows “The Shock of the Insult” goes on to describe the trip to the city and the beginning of the construction of a community. It is in this interim that this loss would arise, this space of uprooting in which certain individuals inhabit, either temporarily or permanently.

“He remembers at 14

He knew what he wanted

He wanted a man no psychiatry

Just to be held to be told it was alright”

Jimmy SOMMERVILLE, Dare to Love, 1995

“Activists of all stripes and queer activists in particular have always looked to popular culture for inspiration and have refused facile distinctions between culture and reality” J. Jack Halberstam, Gaga Feminism. Sex, Gender and the End of Normal, 2012

1984, Culture Club’s Karma Chameleon is still on the British charts, but that same year Frankie Goes To Hollywood’s Relax was added, which was number one for five weeks, I Want To Break Free, with a video featuring all the members of Queen in drag, Careless Whisper, George Michael’s first solo single, Dead or Alive’s You Spin Me Round, Hazell Dean’s Searchin’, Divine’s Do You Think You’re a Man… to all this we can add The Smiths’ debut album, with Joe Dallesandro on the cover. This scenario of (male) “diversity” could lead us to think of a progressive political and social climate, favourable to the demands of this group, but the government, from 1979 to 1990, was presided over by Margaret Thatcher, who would go on to promote, in 1988, Code 28, in force in England until 2003. This legislative norm prohibited “the promotion of homosexuality”, coinciding with one of the most virulent stages of the HIV pandemic.

As Carles Congost (Olot, 1970) has pointed out, the hit lists do not only report musical or stylistic changes, they are a reflection of the contradictions and political and social coexistences of their time. 1984 is a perfect reflection of these gaps and tensions. The 1986 hit We Don’t Have to Take Our Clothes Off (to Have a Good Time) performed by Jermaine Stewart, who would die from complications resulting from AIDS, exemplifies the conservative turn and double standards suffered by many of the performers mentioned in the previous paragraph.

It is interesting to see that another chart-topper, Bob Stanley, in his exhaustive review of music history, Yeah, Yeah, Yeah: The History of Modern Pop, 2013, makes no mention of Jimmy Somerville, nor of his solo career, nor of his time with The Communards or his beginnings with Bronski Beat, a group with which he would enter the Top Ten in 1984 with Smalltown Boy. I doubt that this absence is malicious, the book talks about Divine, the impact of Relax… but it does show the uncomfortable role that has been assigned to a pop performer who built his proposal around a commitment to politics, not only from the enunciation, but by pouring it into the cultural products he produced.

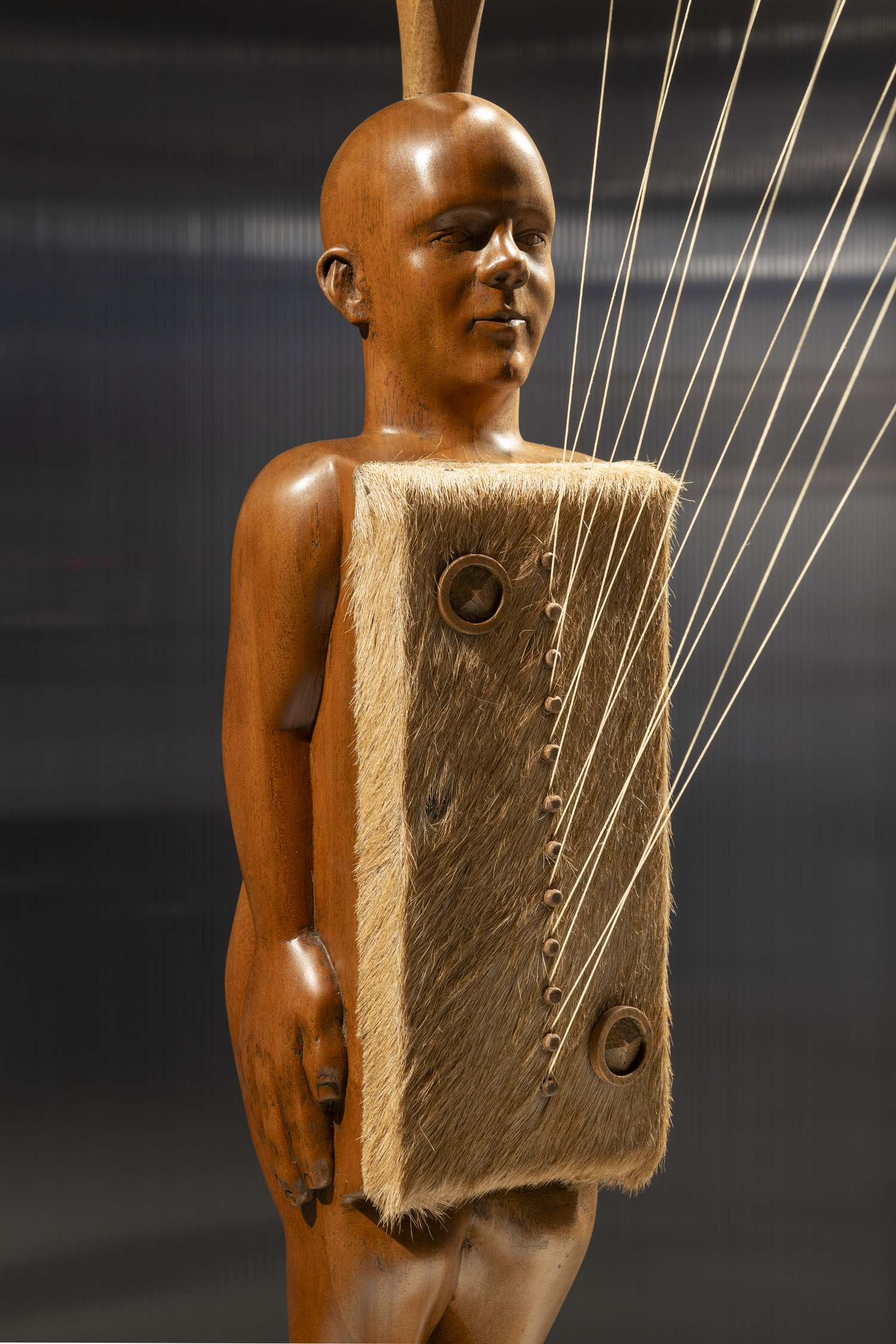

It is precisely Jimmy Sommerville who is the figure in Congost’s project, the origin of which we can find even before the pandemic and in proposals such as Para qué sirven las canciones, Casa Encendida, 2020, or Music as a Foreign Language, together with Jeremy Deller, Es Baluard, 2023.

“Pushed around and kicked around, always a lonely boy

You were the one that they’d talk about around town as

they put you down

And as hard as they would try they’d hurt to make you cry

But you never cried to them, just to your soul

No, you never cried to them, just to your soul

Run away, turn away, run away, turn away, run away

(crying to your soul)”

Bronski Beat, Smalltown Boy, 1984

“Images are not sought, they are imposed: that is the

happiness of art, its promise of bonheur”

Alberto CARDÍN, Expreso de mediodía. 1981

“Where fascism leads a new dance

Where they’d privatize your mother

If given half a chance”

The Communards, Breadline Britain, 1986

The choice of a pop figure as multifaceted as Jimmy Somerville is not a novelty in the work of Carles Congost, who takes the risk of betting on pop as an aesthetic and imaginary.

One of the problems in music is that of gender, a term that is even more omnipresent than it might initially seem. If the delimitation and definition of a “musical genre” implies a defense of purity and an opposition to the surrounding pharisaical formulas, this type of criticism of the impure can also be applied to women, racialized people and anyone who does not fit into the privileged spheres of the heteropatriarchy. While some musical genres are presented as authentic, linked to the marginal -located in the neighborhood or in the roots- and, therefore, with the people. What is authentically popular, linked to truly marginalized groups, is reflected as artificial and constructed: a product.

Publications such as Rolling Stone were already selling T-shirts with the slogan Disco SUCKS! before the Disco Demolition Derby of 1979 took place. At this event, organised during the half-time of a baseball game, the destruction of disco vinyl records coexisted with homophobic proclamations and harangues that were accompanied by riots and acts of vandalism, all of which would lead to the suspension of the game the following day. This event symbolised rage and the defense of the pure and authentic values of (North)/American music. The strategy of domination: to feel attacked in the presence of any “anomaly” and to defend oneself through a real attack.

In response to all this, Sommerville added to his commitment and activism the vindication and appreciation of an entire “other” musical tradition through the political use of versions of Cole Porter, Gershwin, Donna Summer or Sylvester. In this way it was evident that activism also passed through those despised areas of the popular.

“Like the knife of a thief that’s held close to the throat

I’m threatened by you and that cruel way you gloat”

The Communards, Tomorrow, 1987

“The preoccupation appears either as gnawing doubts that oneself might be a “latent homosexual,” or as reactive contempt and ridicule, or hostility and even paranoia. Among young people every kind of nonconformism in a contemporary tends to be thought of as homosexual, whether it be a passion for music or a passion for social justice.”

Paul GOODMAN, Growing Up Absurd, 1923

“Building walls around me

With their legislation

If you only could see

All the lies you’ve believed

The wrong that needs undoing”

Jimmy SOMMERVILLE, And You Never Thought That This

Could Happen To You, 1989

In 2011, Michel Marc Bouchard premiered Tom à la Ferme, a play in which the death of a person creates an infinite loop. It is as if each character were a mirror facing the other: the boyfriend knows nothing about his partner’s family, the mother, like an inverted reflection, knows nothing about her son’s life, the fiction of a girlfriend perpetuates the network of lies, but the appearance of pretending to only know another language multiplies the codes and secrets. And at the centre of this whole network of violence is the brother, who in turn is an echo of the deceased, charged with replicating the violence and submitting to it. Again and again…

It is this vicious circle that we also find reflected in the work on display. As with pop, rural areas, neighborhoods, all the realities that we try to isolate, are in a territory between idealization and demonization. Rural communities must be defined between a refuge of tradition and authenticity, the root, and the container of the crude and uncultivated. This looking in opposite mirrors, the vertigo of configuring an identity from the extremes, is what generates a violence that attacks everything that breaks this precarious balance between opposites. The breaking of the norm, as Tom à la Ferme’s brother comments, is multiplied by twenty in these closed environments and must be redirected or expelled.

By placing Congost this loop in an idealized representation of the rural, like the fantastic territory inhabited by other of his previous works, he reaffirms the character of pop, revealing the violence against the sign and against the person.

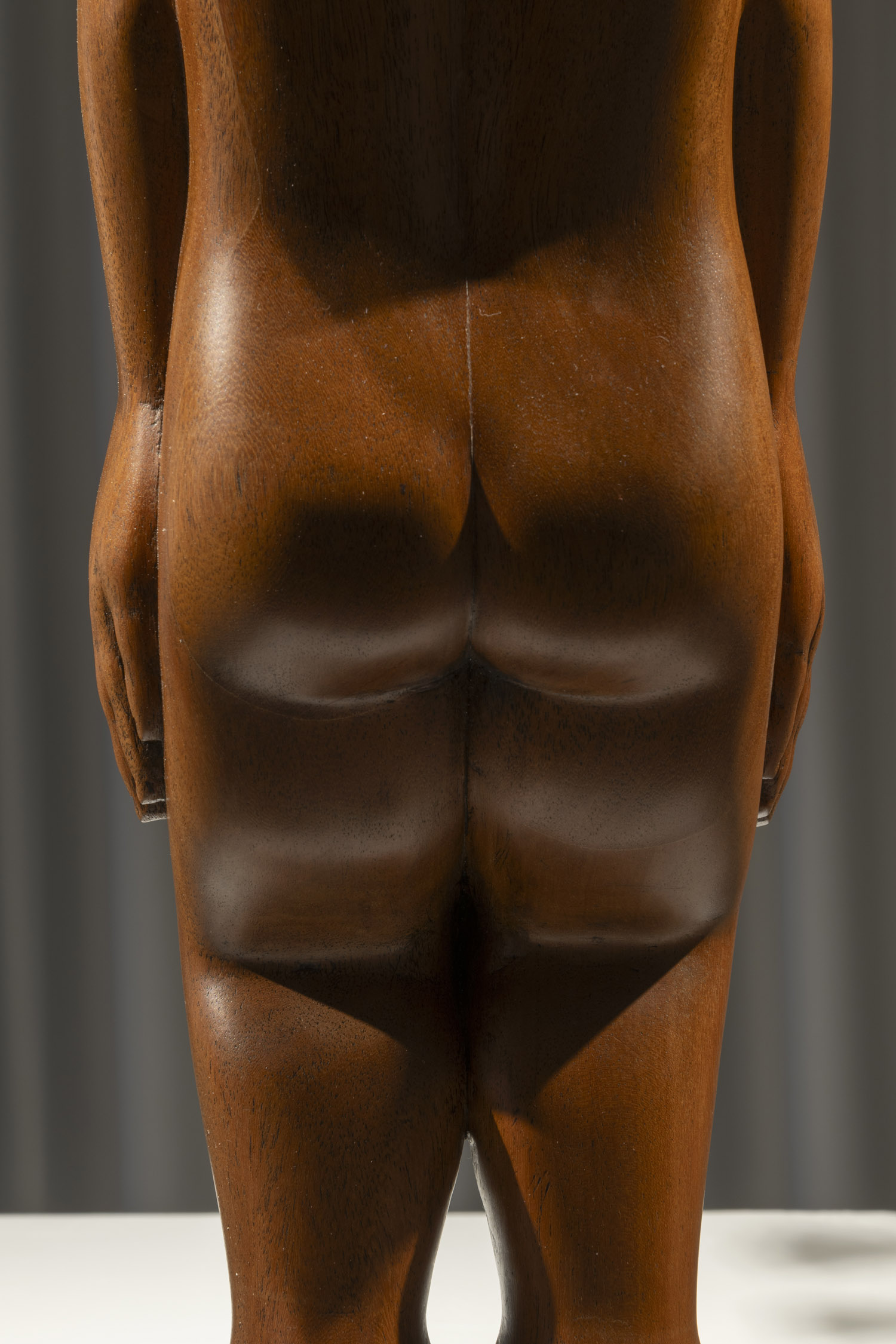

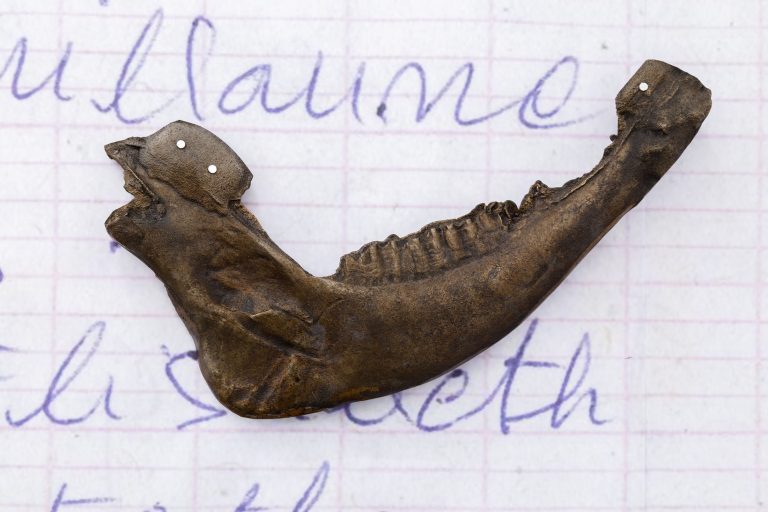

Jimmy Somerville’s harp is not just an image, it is the subject itself, another body trapped in a voice, in a string of words that are violence and that also trap the speaker in their net. The simple displacement of a pronoun, the imbalance in social reproduction that this atmosphere imposes is what starts the suffering again. Sisyphus trapped by the sirens, captured in a net thrown by Sisyphus himself and interweaving music and song; and, like myths, adopting its most rudimentary form, like the image of Somerville performing Scream in 1983 in Framed Youth: The Revenge of the Teenage Perverts; built from activism, this film includes the first song published by the author, just a drum machine and a poem, almost an exorcism, in which the word is what defines again, in which the names have been rewritten without having forgotten the previous ones, in which a scream is uttered.

“I knew you’d show up someday. I don’t know you. I don’t know your name, but I knew you’d come. Out in the field, at the far end of the field, there’s the ditch where we throw the cows. The sick cows when they die. One more carcass, nobody will ever notice, and believe me, nobody will want to go snooping around there. (…) You’ll get in your car and drive away. Then my mother will forget. And he’ll be dead for good. Then everything will be fine. Do I need to repeat that?”

Michel Marc BOUCHARD, Tom at the Farm, 2011

“My man love my first love

My closetness and pain

My lying my deceiving

My rivers keep on crying (…)

Machismo my manhood

My wanting just to scream

Scream yeah yeah yeah”

Jimmy SOMMERVILLE, Scream, 1983

Eduardo García Nieto

Education, critic and curator