Artist: Camilla Steinum

Exhibition title: symptom, sympathy

Curated by: Kristina Scepanski

Venue: Westfälischer Kunstverein, Münster, Germany

Date: October 24, 2020 – April 5, 2021

Photography: all images copyright and courtesy of the artist, Soy Capitán, Berlin and Westfälischer Kunstverein

The Berlin-based Norwegian artist, Camilla Steinum (b. 1986 in Oslo) likes to work with everyday materials, shapes and objects, which she distils into installations and assemblages that generate new contexts, effects and meanings. Crucially underpinning this approach is an emotional connection to these objects and a physical experience of space. Steinum has devised a new expansive installation for the Westfälischer Kunstverein that focuses on the influence objects and spatial experience have on memory and mnemonic techniques, trans-forming the exhibition hall into a course by means of an architecture reminiscent of a pen or a cage.

Since the beginning of the year and more intensively during her six-month residency at WIELS in Brussels, Camilla Steinum has been researching the his-tory, training and construction of memory. Whereas some memories are suddenly awakened, commonly triggered by unconscious impulses (smells, places, images) and are often linked to subjective emotions, the summary recollection of certain subjects and facts is sometimes difficult and can be trained using certain techniques. When doing so, one makes use of what tends to happen subconsciously: one visualises familiar spatial environments to enhance the recall of information (according to the so-called “loci method”) or one translates them into particularly striking images (such as numbers, using the “mnemonic major system”). What emerges here is the way in which memory functions, either in an individually spontaneous or constructed form, as well as how much it is shaped by personal experience, interests and subconscious imaginings. If, for example, the chosen image is insufficiently striking, it won’t find purchase in the mind – the mnemonic will fail. There is a relationship be-tween memories and encounters with art residing in these dual aspects of place and the striking nature, i.e. impact, of images and objects: both in-scribe themselves in our minds in a similar way and react to what is already there – occasionally on an emotional level.

The first wave of the Covid-19 pandemic in the Spring of 2020, which also decisively restricted all of our movements in physical space and ushered in strict routing protocols within exhibitions, coincided with Steinum’s artistic exploration of scientific theories about human memory and methods of cognitive training. Harnessing these “coddling” directives as her point of departure, Steinum set out to structure the Kunstverein’s large exhibition space, which itself normally allows the greatest possible freedom of movement, in such a way that a guided tour, a “right way”, could be laid down, but still leaving options open. The customary mode of wandering freely around the exhibition space is thus replaced by regimentation. What influence does this intervention have then on the way art is viewed and apprehended?

Structures recalling pens or cages (01), painted a shiny deep purple, delineate a course of sorts that can be perambulated in various directions, but which forces us to make decisions. The serried bars create an almost hypnotic sense of confusion and subtly coerce museum-goers to keep moving around the space. This is because the exhibition cannot be assimilated in its entirety from a single viewing point; you literally have to walk around it to take it in.

Artefacts distributed around the course, perhaps kindling memories in the mind of the viewer, include the three undulating, carved wooden objects (06,07,08) that formally embody a further development of the “puzzle” work in the small exhibition room (14). Three dogs, made from small wooden puzzle pieces, are playfully fighting one another. Dogs, and the way humans relate to them, served Steinum in this earlier series as a foil with which to negotiate the duality of relationships per se. Loyalty, attachment and caring are often countered by aspects of power and violence, which may range from incursions into individual freedom all the way to dominance. Thus, ambivalence in the subjective relationship to the world once more shapes the motifs and focus of Steinum’s interest and investigation in this context. By focusing on the dog as a motif, she has also chosen a powerful image that (as the mnemonic techniques recommend) is capable of triggering emotions and associated memories, which are eminently difficult to shake off. And by also cogently opting for the emblem of a puzzle, we instinctively recognise the symbolic search for the supposed ‘perfect fit’, for mutual perfection.

Similarly, the idea of care and security is evoked in the fleece blankets (10,11), which is immediately undermined by the fact that Steinum has dyed them patchily, affixed straight ribbons to them and rudely attached them to the wall with menacing nails. Dogs, blankets, the colourful paint on the bars: the associations are varied and subjective, but it emerges that these particularly powerful memories are often linked to one’s own childhood. But here too, Steinum has deliberately laid contradictory trails that eschew clarity. Does the supposedly joyful playpen perhaps not evoke a prison cell after all? And who is being punished (or pacified?) by the oversized rubber belts hanging loosely over the bars? All these chains of association, which Steinum has laid out as clues in her installation and in the objects, lead us individually to the most diverse recesses of our (sub)conscious minds and show us, quite by the by, how we can train our memory: by allowing ourselves to react to associations and create mental images that do not conform to rea-son alone.

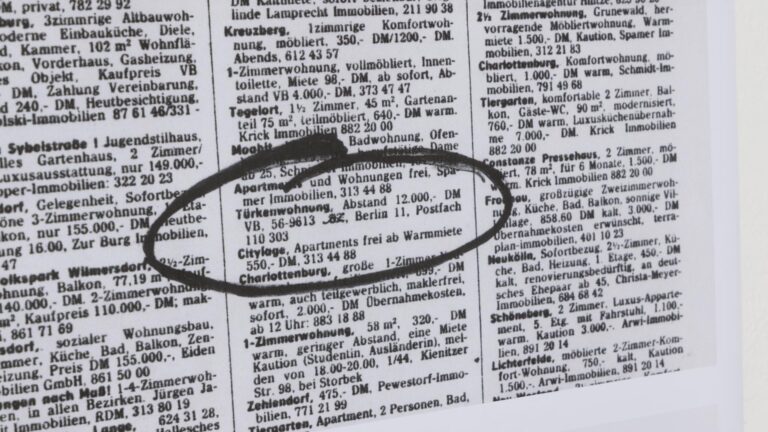

Reason does indeed take its place in the exhibition in the form of numbers that appear in several places: on the wooden sculptures, in the artificial rubbish sacks made of paper (03,04,05), on the lottery tickets (09) and – theoretically – also on the playing cards (02). Numbers are precise, they denote fixed and incontrovertible information, and yet they too are often individually charged with ancillary meaning, so that even a completely rational number has the power to trigger a certain feeling. This potential is enhanced in the case of numbers on lottery tickets or playing cards – some may speak of lucky numbers or destiny cards. So here too, rationality and a sanguine belief in fate are once again polar opposites.

Interestingly, Steinum’s playing cards, apparently distributed casually in the shadow gaps of the exhibition space, are unique inasmuch as they don’t have a face or front side. Both sides are printed with 130 different variations of the back of a pack. They are thus utterly devoid of any information regarding fate as such, or even whether one might have a “good hand” or not – both in a game or in life. Worse still, they are more likely to cause confusion due to Steinum’s hypnotic design – just like the backs of classic playing cards: you don’t want anyone looking at your hand, plus you are at pains to deceive or even confuse your opponent.

Titled Instruction and made specifically for the exhibition with notes and references from the overall exhibition concept, Camilla Steinum views the artist’s book as an extension of the show. Here, too, you will be confronted by ambivalence: do you want to follow the at times questionable advice and stick to the “guided tour”, interpret the book as a friendly, well-meaning aid, or rather see it as a restriction and constraint? Let it be known, you will definitely not be told off if you dutifully follow the “instruction” in the book and take the entreaty to “pick a card” literally!

In this sense, Camilla Steinum’s masterfully enacted maze of ambivalence – oscillating between care and compulsion, freedom and restriction, emotion and reason, a child’s paradise and a penitentiary – may help us gain more confidence and courage in our own, betimes wild imaginings and associations. It may even train our memory.