Public Gallery is pleased to present Camera Obscura, a group exhibition of painting, sculpture, installation and video. Engaging themes of theatricality, illusion, doubling and decoys, the exhibition probes the mechanics of image-making – its title referencing an optical device that functions by projecting an image both upside-down and reversed into a darkened chamber. Used historically as a drawing aid, the camera obscura helped artists trace projected images with greater perspective and accuracy, and served as an important precursor to the photographic camera. In attempting to render the real, it produces an inversion, evidencing the inherent mediation of all images. With these ideas in mind, the artists in this exhibition employ strategies that challenge the authenticity of an image, often referencing the art historical canon, and privileging trickery, manipulation, deception and artifice in their works.

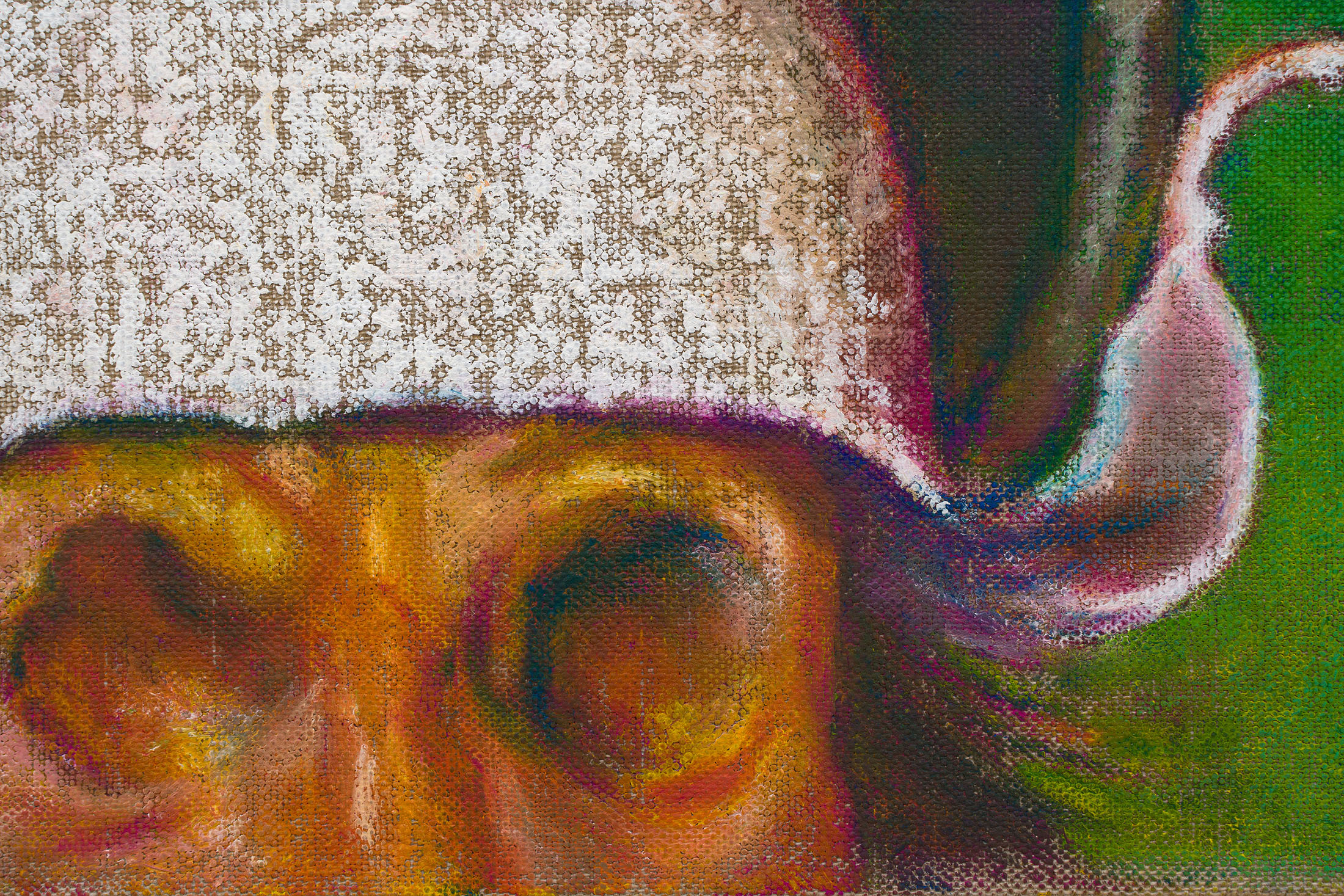

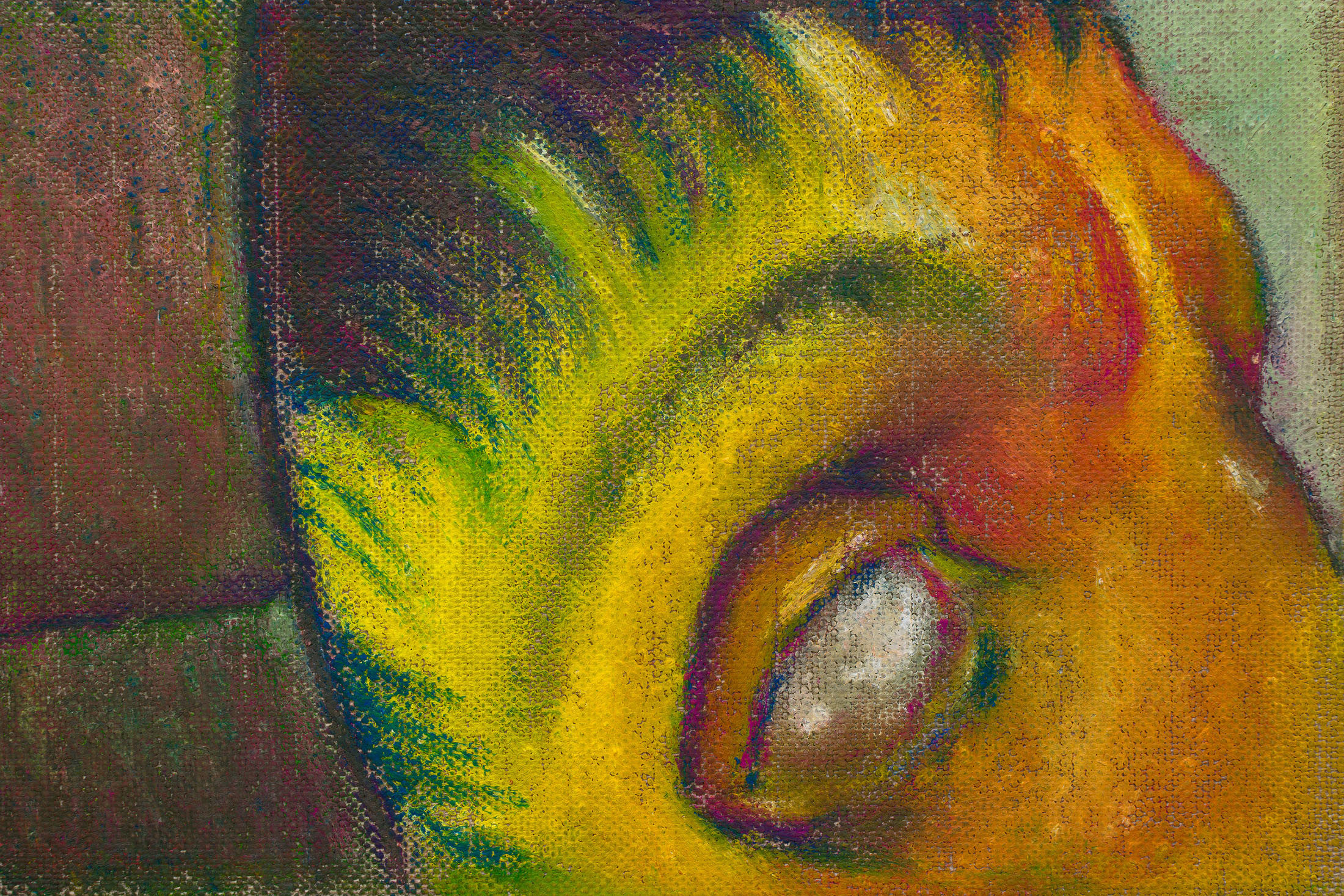

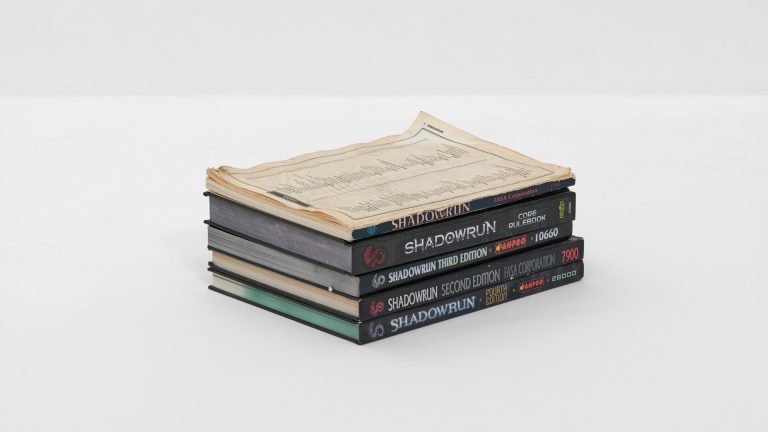

Lyndon Barrois Jr.’s A Witnessing (After Pieter Bruegel the Elder) (2025) occupies the gallery vitrine and reinterprets works by its titular reference to interrogate the historical gaze and its entanglement with race, ethnography and systems of classification. Barrois Jr.’s oil stick paintings on Belgian linen excerpt and reframe fragments of The Blind Leading the Blind (1568), while sculptural elements resurface motifs from Netherlandish Proverbs (1559), The Beggars (1568) and Peasant Wedding (1568). Alongside Barrois Jr.’s ‘cabinet of curiosities’, replicas of color and scale charts — tools from museum registries, archaeological study, and forensic science — suggest a taxonomy of visual knowledge and power.

In Mannequin Death (2016), a short video by John Miller and Richard Hoeck, couture-clad mannequins — human surrogates which function as “empty subject positions”— are hurled from an Alpine mountainside to the sound of various thumps and smacks appropriated from martial arts movies. The spectacle vacillates between slapstick and grotesque, recalling Immanuel Kant’s theories of the Sublime as much as Mario Perniola’s writings on “the sex appeal of the inorganic”. Bringing together high and low references from the paintings of Caspar David Friedrich to the MTV show “Jackass”, Miller and Hoeck’s three-minute black comedy critiques the commodification of human desire with the absurdity and horror of a false double.

Tiffany Wellington’s Witching Hour (2024) further complicates the relationship between subject and object, narrative and prop. A pair of worn boots assumes a ghostly role within their filmic mise-en-scène, illuminated by car headlights and echoing Antonin Artaud’s The Theatre and Its Double (1938) — privileging lighting, sound, and visual intensity to stage an embodiment in space. Wellington’s total installation is accompanied by a single channel sound work, a reference to Fly Me to the Moon by Frank Sinatra, assuming a bizarrely disjointed atmosphere that recalls 1960s ‘showbiz’ with an air of possibility and romanticized nationalisms.

Taylor Simmons’ Free before 12 (2025) depicts a crowd of figures huddled together outside a nightclub beside a red car. With heads lowered, their downward gaze gives the work a feeling of routine drudgery, of processions and rituals, or collective performance. The darkened charcoal palette stands in contrast to his work Writing on the Wall (2025), dominated by sharp diagonal and horizontal interruptions and brightly colored figures. Here, the central subject occupies a stage-like space and suggests an awareness of the viewer’s presence, as if posing atop a ladder beside a cast member reading lines below.

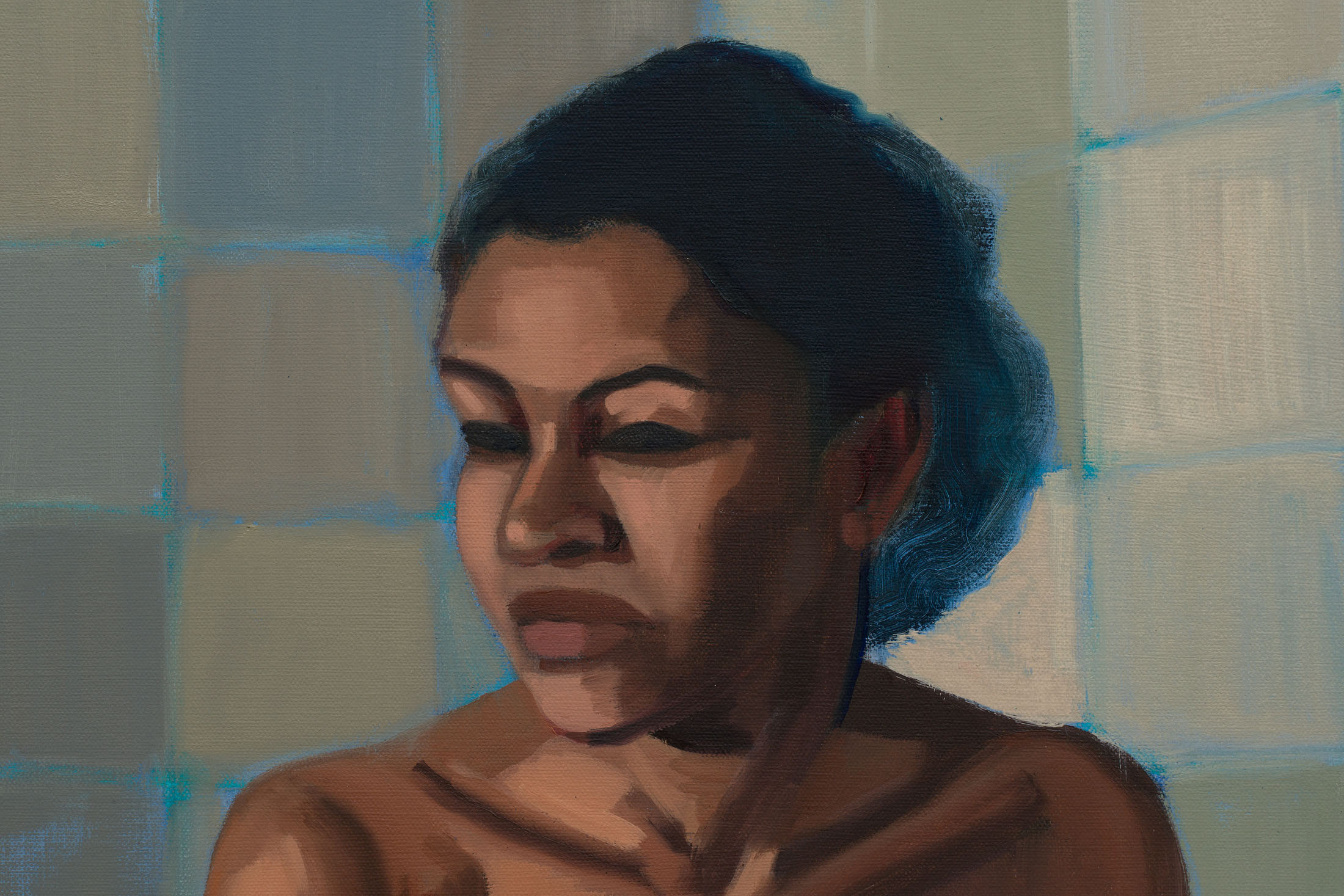

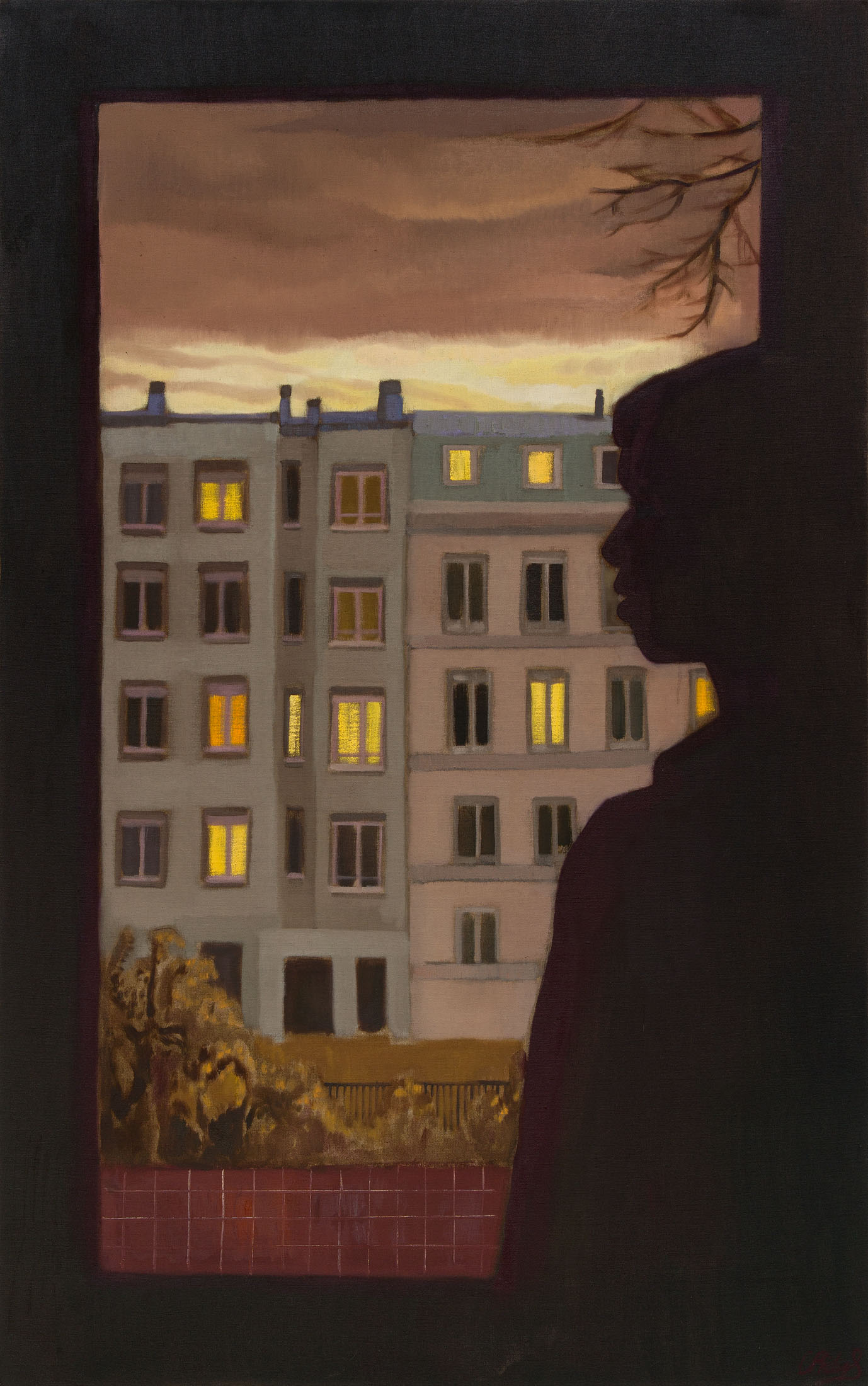

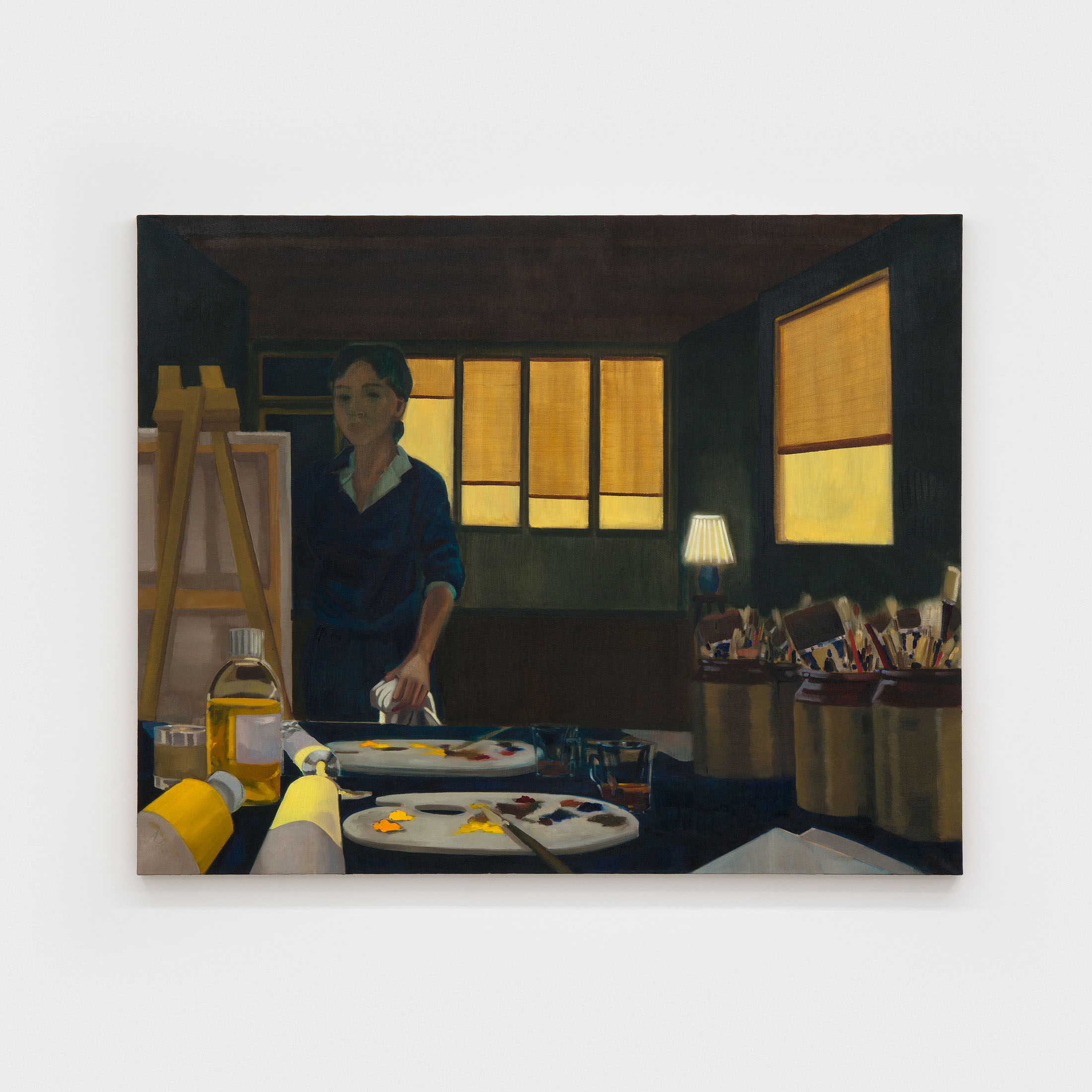

In the quiet paintings of Cece Philips, the intensity of spectacle gives way to moments of intimacy and interiority. The theatre, the stage, the window and doorway all become frames through which the artist explores ideas of spectatorship and voyeurism. Her subjects embrace both a desire for solitude as well as the ache of loneliness, lending the work a psychological and narrative depth, and call to mind Laura Mulvey’s essay Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema as well as W.E.B. Du Bois’ concept of double consciousness.

Russell Perkins’s two-channel silent video Card Players (2018) presents a group of professional online poker players competing in a tournament. Based on a 19th-century painting by Theodoor Rombouts of the same title, the work stages a social context in which we see the workings of a financial market, examining how it enables and intersects with heteromasculinity and its performative nature. Perkins playfully displays one channel upside down, mirroring the format of a face card and reinforcing the notion of mutually opposing points of view, playing on sleight of hand tricks and the theatricality of a good bluff.

Camera Obscura plays on the slippages and subtle frictions between the real and replica, subject and surrogate. Across a range of media, the artists in the exhibition destabilize fixed ways of seeing, using theatricality, inversion, and artifice to question the mechanics and politics of image-making. From haunting mise-en-scènes to reimagining histories both art-historical and social, the works in this presentation expose the constructed nature of representation and the systems that underlie it, intertwining the invested voyeur with the object of his gaze.