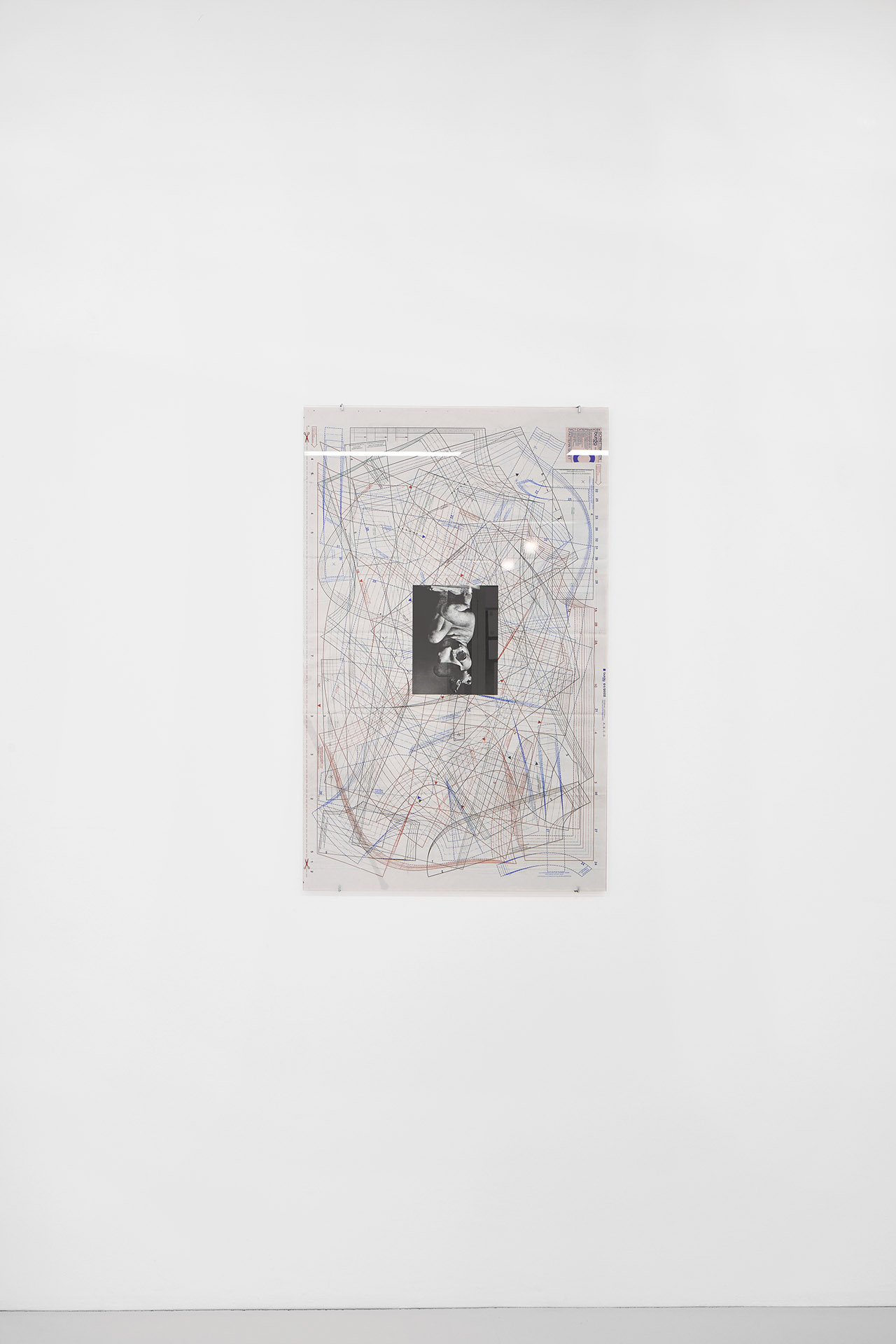

Artists: Nicolás Lamas, Barbora Zentková & Julia Gryboś

Exhibition title: Bone Tone Shelf Self

Curated by: Jan Zálešák

Venue: Center for Contemporary Arts Prague, Prague, The Czech Republic

Date: May 6 – June 26, 2022

Photography: © Filip Beránek ©Nicolás Lamas / all images copyright and courtesy of the artists and Center for Contemporary Arts Prague

Sit down, stand up: lie down and sleep. Approaching the horizon, clinging to dreams. In my room. A room? Somewhere to rest my weary bones. Such luck! My eyes alight. Never rest, ever!

Prologue

On his way to the gallery, he sensed the thickening and thinning tissue of the city. A narrow street that seemed to be holding its breath most of the day, only to exhale sharply from time to time. A children’s playground in a park, still breathing calmly in the morning. On a concrete terrace that offered no particular view and was probably simply a temporary extension to the staircase connecting the lower and upper levels of the embankment, a homeless man wrapped in a thick hooded coat was tottering around. It must be the same guy who was lying on his side at the same time yesterday, with his face turned to the pavement, as though he were dead. This bridge is really wide, he thought, as he made his way to the other side of the river, absent-mindedly taking in the vegetation on the slope opposite, and then the pedestrians released in a clump by the green man of the crossing before dispersing at different speeds. Each of them had a reason for walking, though most were probably doing it for health reasons – this shortish guy in his fifties in blue sneakers wearing large earphones for sure. At the same crossing he waited for the green man and then made his way up the narrow staircase angling up the slope. Today he took the stairs two at a time. He wasn’t in a hurry, but he didn’t stop to take shots of the panorama. The little recess in the wall where the homeless man had slept yesterday, his back turned to the professionals passing by in both directions, was empty. Was it him, the one lying on a bench nearby, surrounded by bags and a wheelie suitcase? Just a short parabola around the 1950s glass pavilion (he was surprised to see that the basement co-working area was already filling up, even though it wasn’t yet nine) and then out of the greenery. He stumbled in the same place as yesterday (cursing under his breath), then fifty metres in a straight line, two blocks down, hang a left and enter the second courtyard…

Clay and bones

Beside the drapes, beneath which lies dust from the camomile buds, there is a mattress on the floor covered in a layer of clay. While installing the exhibition, it served for a while as a spare desk, on the top of which things piled up haphazardly. Temporary constellations, rapidly changing, accreting and abating layers, ephemeral events of which nothing remained but fleeting memories that would have long since vanished if I hadn’t just written them down. There are almost eighty kilos of clay. The weight of a human body, which drops a little when all the water has evaporated. The soft “tissue” of the clay then hardens, and the temporary fusion with the foam of the mattress becomes a little more complex again. Beneath the clay, that strangely (in)animate assemblage of the organic and anorganic, the mattress is divided into zones – hard and soft, actively promoting good quality sleep through alternation. Yielding at the shoulders and hips, firmer where the body is more supple. The slowly exhaling clay is as flat as the spine of a body lying on its side on a medical mattress. I imagine for a moment such a body, as it lies with its back to the curtain, feet towards the entrance.

Unlike its long bones, which continue to integrate it into the realm of nature, the modern human spine is an authentic and somewhat sad symbol of humanity. The hunched back, forever twisted unnaturally depending on what its owner does to earn their daily bread (and ideally a little extra), seems to have nothing in common with the graceful lines of their limbs, nor even, paradoxically, with the “ergonomically” designed work environment, reflecting more the abstract logic of capital than the defiantly material and fatigue-prone nature of the body. Ironically, the hapless spines of homo erectus only straighten out in their sleep. Exhale and inhale. Little by little, the world enters the body and then leaves it again.

Things and words

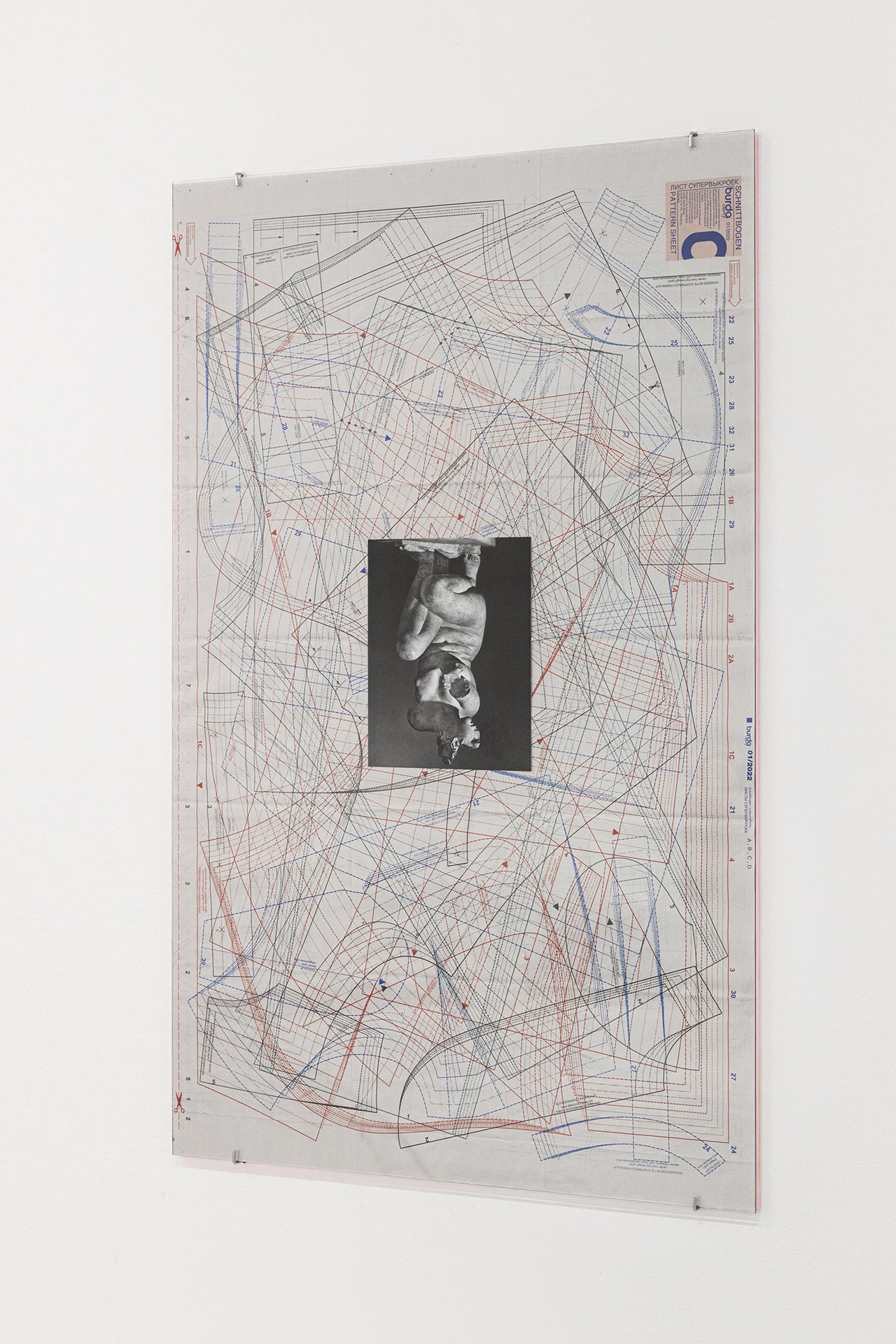

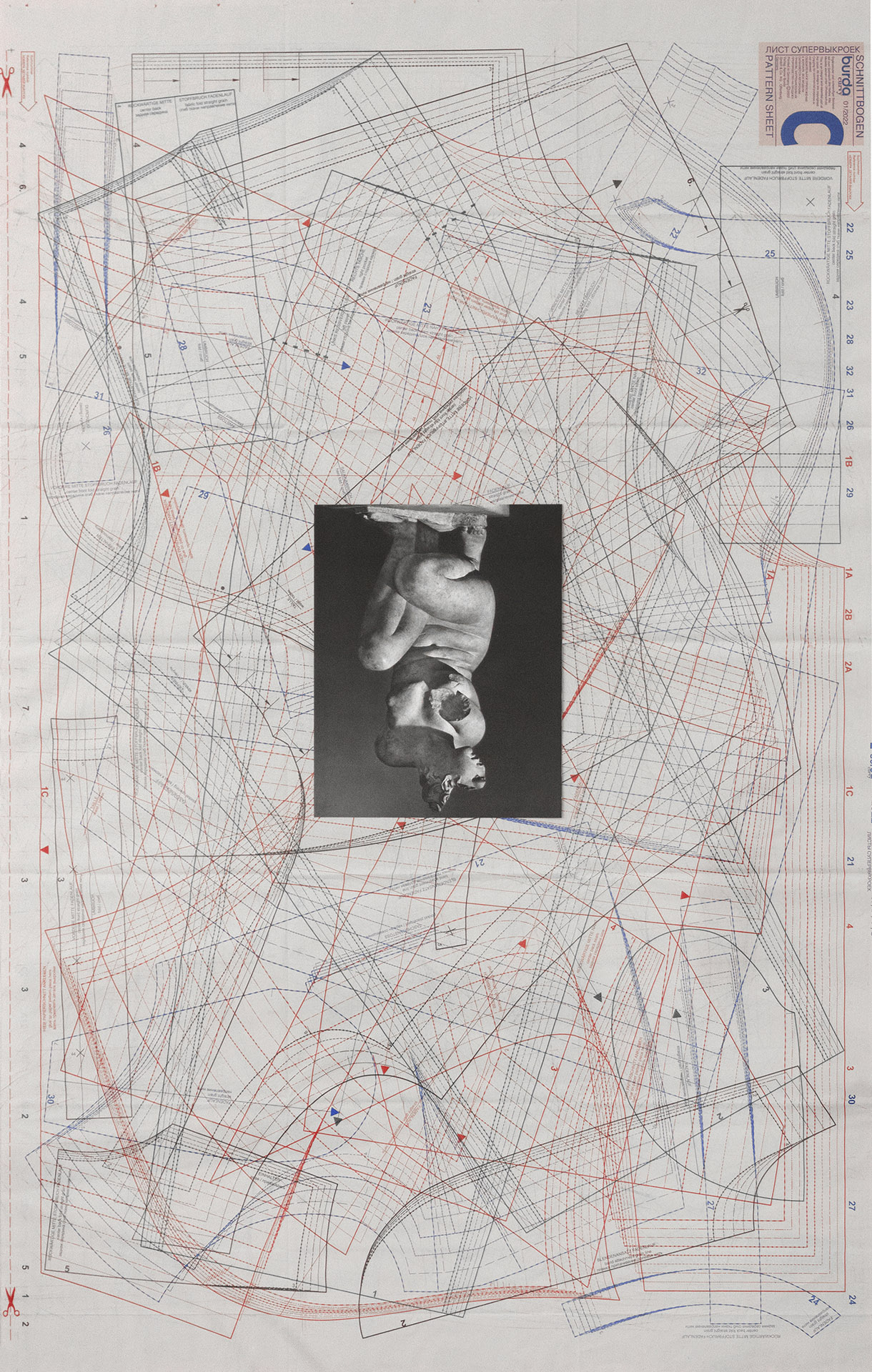

There is more in the gallery. Not just the mattress and clay and curtains and bones. There is also a black and white picture taken from a book, a sketch of a needlework pattern from a magazine, several glass plates. A metal bench and metal bench-shelf. The gallery is full of things. But it is also full of verbs. In 1967, Richard Serra wrote a long list of words representing “actions to relate to oneself, material, place, and process”. Verbs such as to roll, rip or prop up could be read as instructions for creativity as well as autonomous images. The exhibition Bone Tone Shelf Self has its own list. To burrow, rest, cling, merge… These denote events and processes that can effect(uate) both human bodies as well as things and what they do (or what happens to them). Words pass between subjects and objects and open themselves to metaphorical reading by settling “somewhere in between”. Just as the pigment released from flowers in a hot bath dyes the texture of cotton, my gaze clings to the threads of yarn drawn above and around a metal pipe and flowing freely down. It follows the rhythm of their trajectory and after a while it slides (trickles) down as my attention fades, when I lose the thread, when the taut vector of attention is dissolved by weariness. If my gaze behaves in the same way as water, what does that say of my relationship to the threads of yarn that ripple on the floor? Is it one wave, one movement that passes through everything here within (before disappearing without)?

(Un)rest

In the work of Nicolás Lamas and the artistic duo Barbora Zentková & Julie Gryboś, two different but complementary ways of being creative, or rather creating meaning, meet in the exhibition Bone Tone Shelf Self. One is assemblage, in which the proximity of things, a proximity almost “within reach”, is a prerequisite. The second is an atmospheric installation, in which air remains between artefacts and meaning emanates from their mutual positionality, somewhere in the space between them. In addition to the verbs recalled in the previous paragraph, the nouns describing process are also important here: releasing, spilling and diffusing, stretching, tightening and combining.

In the creation of assemblages, there is an encounter between things that have up till now passed each other by in their movements. It is the degree zero of the demiurge – plucking objects from their trajectory and bringing them close to each other in one place. Things that move quickly, like goods travelling between production warehouses, depos, e-shops, and delivery services, find themselves in a gallery next to things that have almost stopped moving, or alongside artefacts created specifically for this event. These things are mostly not here in their entirety. The completeness of shape, the ideal state of the product when it leaves the production line, or the body at the moment of birth, is a matter of a brief, fleeting moment. Then entropy takes over. Nevertheless, it is this openness to extinction and decay, unrest, setting things in motion and preventing anything from lasting forever, that lends the world meaning, rather than permanence and quiescence.

But there are different kinds of unrest. Being dragged somewhere is not the same thing as setting one’s coordinates. One of the reasons we have been able to identify with objects so easily in recent years (and the years are adding up) is that within the computer accelerated economy of late capitalism the difference between the status of workers and products has shrunk to almost nothing. Whether one or the other, we are but items, digital data subject to calculation and speculation, and as such we only make sense in flows. Suspended movement equals death. Not in an ontological, but a purely economic sense. And economics today has now successfully pushed ontology to the very brink of social relevance. Suspending objects in their circulation is a prerequisite for reflecting upon their meaning, but also a gesture of political defiance. An unwillingness to refurbish your room every few years, change your clothes and shoes every season, and regularly update all of your software and hardware is just as undesirable from an economic perspective as an occupation preventing the completion of a pipeline.

The static nature of contemporary art exhibitions is an acceptable departure from the norm, a deviation within the system that at the same time does not fundamentally disrupt it. A temporary autonomous zone. Lol. And yet… By imitating the gestures of objects and things that are already in the gallery space; by slowing down, pausing, lingering, alighting, unwinding… through these actions we can escape the entrenched trajectories we found ourselves on in the morning, rid ourselves momentarily of what we have already become, so that we can lose ourselves in thoughts of what we might be.

Barbora Zentková & Julia Gryboś have been working as an artistic duo since 2010. Their starting point is the experience of painting, a discipline both of them studied. However, since the mid-2010s they have focused mainly on the creation of locally responsive interventions and installations, which often become the scene of performative audio events. One of the central motifs of their work involves the negative effects of late capitalism in the form of overwork, anxiety, and chronic fatigue often leading to collapse. Barbora is from Slovakia and Julia from Poland. The two currently live and work in Berlin.

Nicolás Lamas works most often with assemblage, which he regards not simply as an artistic technique, but above all a speculative tool for exploring the boundaries between the human and non-human world, between culture and nature, and between diverse systems of being and cognition. The ontological aspects of assemblage are as important for him as the aesthetic. We might describe his working method as a kind of wild archaeology, the practices and particular aesthetic of whose institutions and collections he derives inspiration from. Nicolás is originally from Peru. At present he lives and works in Brussels.