Stuffed Trauma: On Benjamin Slinger

by Pierre-Alexandre Mateos

I hate children. All of them. They’re parasites. They suck out our calcium, they terrorize us, they eat us alive from the inside.

Benjamin Slinger makes stuffed animals. Not like Mike Kelley or Lutz Bacher — but plush toys you’d imagine in the bedrooms of the Menendez brothers. For those who spent the winter under a rock: the Menendez case is the story of Erik and Lyle, two Beverly Hills sons who shot their parents with a shotgun before going on a golden spree. Rolex watches, a house in West Hollywood, the Bel-Air Hotel, Gucci outfits — they indulged in their inheritance until they confessed everything to their therapist.

Apparently, Erik Menendez even wrote a script titled Friends, in which he narrates the murder of his parents — inspired by the 1987 film Billionaire Boys Club, where a group of wealthy young men run a Ponzi scheme and end up killing one of their investors. Netflix, via Ryan Murphy (Nip/Tuck, Dahmer, American Horror Story), turned the case into a global hit. The homoerotic tension between the two brothers is everywhere — palpable, lingering.

But Benjamin Slinger isn’t interested in the murder. Nor in what came before: the years of sexual abuse, repeated rapes by a despotic father who justified everything with ancient rituals. The Menendez father invoked Sparta, Rome — the idea that pain is the path to manhood. He strangled their genitals with cords, imposed blowjobs, sodomized them. As he said: “Romans created pain to learn how to suffer.”

What really interests Slinger is the virtuality of the fiction. They’re not primarily interested in what actually happened to Lyle and Erik Menendez, but in what could have happened — or more precisely, in the narrative space that opens up when facts become unstable, when trauma enters the realm of mediation, and real-life violence becomes content.

The Menendez case, like many others in the true crime ecosystem, stops functioning as a closed story with a moral arc and becomes a kind of narrative container — a site for projection, speculation, and identification. Once contested in court and filtered through media — particularly through the sensationalized lens of true crime — the event is no longer bound to empirical truth. It becomes malleable, plastic, open to reinterpretation by audiences who consume it not as legal history but as participatory fiction.

Ryan Murphy gave ample space to the subjectivities of all parties — the brothers, the parents. The abuse is not denied, but aestheticized, reframed, suspended. The brothers’ guilt becomes less a verdict than a thematic hinge — a way for viewers to entertain their own buried fantasies, like the idea of killing one’s parents, breaking the generational chain, but from a position of safety, distance, even aesthetic pleasure.

In this sense, the case acts as a vessel for collective trauma — a placeholder for fantasies of revenge, power, escape. It allows society to simulate transgression without consequence, to rehearse primal violence through neatly packaged episodes, docuseries, reenactments.

There’s also a kind of postmodern detachment at work — a flattening of historical violence into a consumable, repeatable loop. Like a murder meme. Like subconscious fan fiction.

The Menendez brothers become less themselves and more like avatars — empty signifiers onto which various cultural anxieties are projected: class privilege, the failure of the nuclear family, repressed sexuality, the blur between victimhood and monstrosity. Their story becomes mythic not for its uniqueness but for its reproducibility — its availability as a dark fantasy kit. What happened matters less than how we keep using it. Slinger reproduces two plush toys — 150 cm tall blue bunnies — supposedly owned by the Menendez brothers. Baby-blue softness with pharmaceutical design: they look like OxyPharma mascots made to sell opioids to children. Everything is too clean, too sweet. Behind the cuteness: horror. Behind the teddy: rape.

Slinger conjures an entire epistemology of childhood suffering. From mythologized torture (Zeus, Ganymede, Chronos) to Schwarze Pädagogik, the dark pedagogy of 19th-century German education. Punishment becomes ritual. Like Daniel Paul Schreber — Freud’s patient and author of Memoirs of My Nervous Illness (1893) — who fantasized about being sodomized by God, impregnated by the Sun. Schreber, too, was shaped — or broken — by a tyrannical father, Moritz Schreber, evangelist of orthopedic control and moral training through pain.

In another piece, a mirrored IKEA drawer floats mid-air, suspended by a black rope and pulley system. Balanced, tense. Atop it sits a replica of the Horned Helmet — a grotesque armor piece gifted by Emperor Maximilian I to Henry VIII, now the logo of the Royal Armouries Museum in Leeds. The replica was made from public-domain scans by artist Oliver Laric. Grinning teeth, bulging eyes, stubbly chin. In the 16th century, horns meant shame — cuckoldry, devilry. The armor became a symbol of disgrace. Henry may have worn it for courtly spectacle. Now, it weighs. It suffocates. It humiliates.

Like a shame mask: an iron muzzle designed to inflict silence and pain. Used on women who spoke too much, it pressed a metal tongue inside the mouth — sometimes sharp, forcing the wearer to bleed and swallow their own blood. Known as the Katzenbeiße — the cat bite — these devices evolved into full metal head cages, animal-shaped: donkey, pig, monkey. A bestial taxonomy of disgrace. The goal: to degrade, humiliate, animalize.

Next to the Horned Helmet, this phallic armor warped by shame and mockery, sits a Regency-style lamp. A classic WASP trinket, the kind you’d find in Trump Tower or the antiseptic villas of Palm Beach. A domestic object soaked in reactionary opulence, a fetish for the imagined grandeur of the Old World. Much like wealthy Jewish families in the 19th century who mimicked aristocratic taste, Regency style here becomes a baroque parody of power — grotesque imitation, bloated pastiche, self-parody.

In 1980s New York, this kind of maximalist taste was in vogue among interior decorators — often gay, often ill, most now dead from AIDS — who transformed apartments into fin-de-siècle sanctuaries. Sometimes morbid homages to Proust’s Guermantes, to an imagined aristocratic decadence rendered even more tragic through a camp lens.

Slinger’s installation plays on this ambivalence — drawing from decorative arts (the lamp), minimalist sculpture (the IKEA drawer), and circus aesthetics (the Horned Helmet). Through strategic arrangement, they build a symbolist hybrid: part consumer object, part historical relic — paradoxically free to reproduce, thanks to its public-domain status. There’s a hint of Haim Steinbach here, though without the fixity. What Slinger introduces is the possibility of collapse, the threat of disassembly.

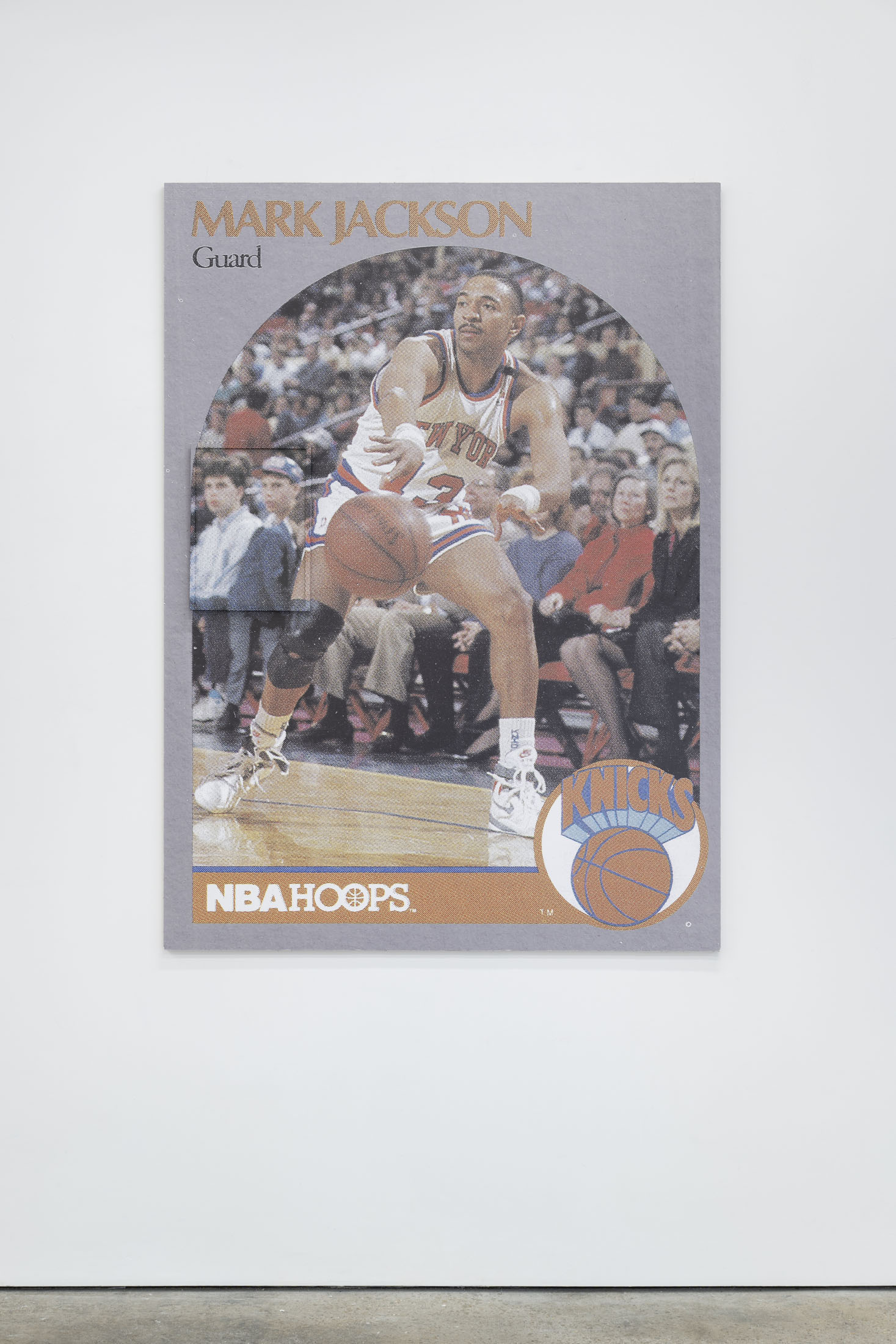

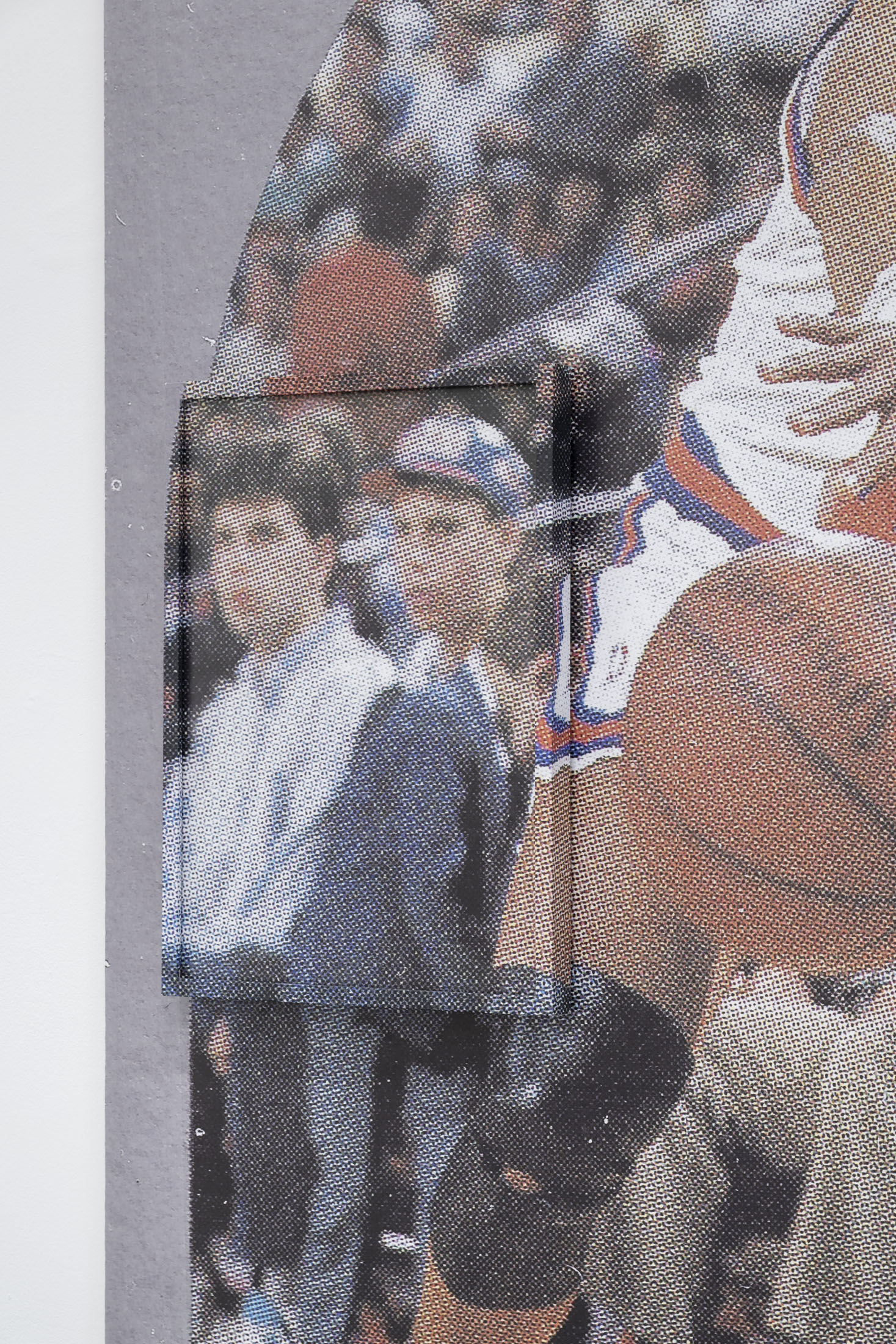

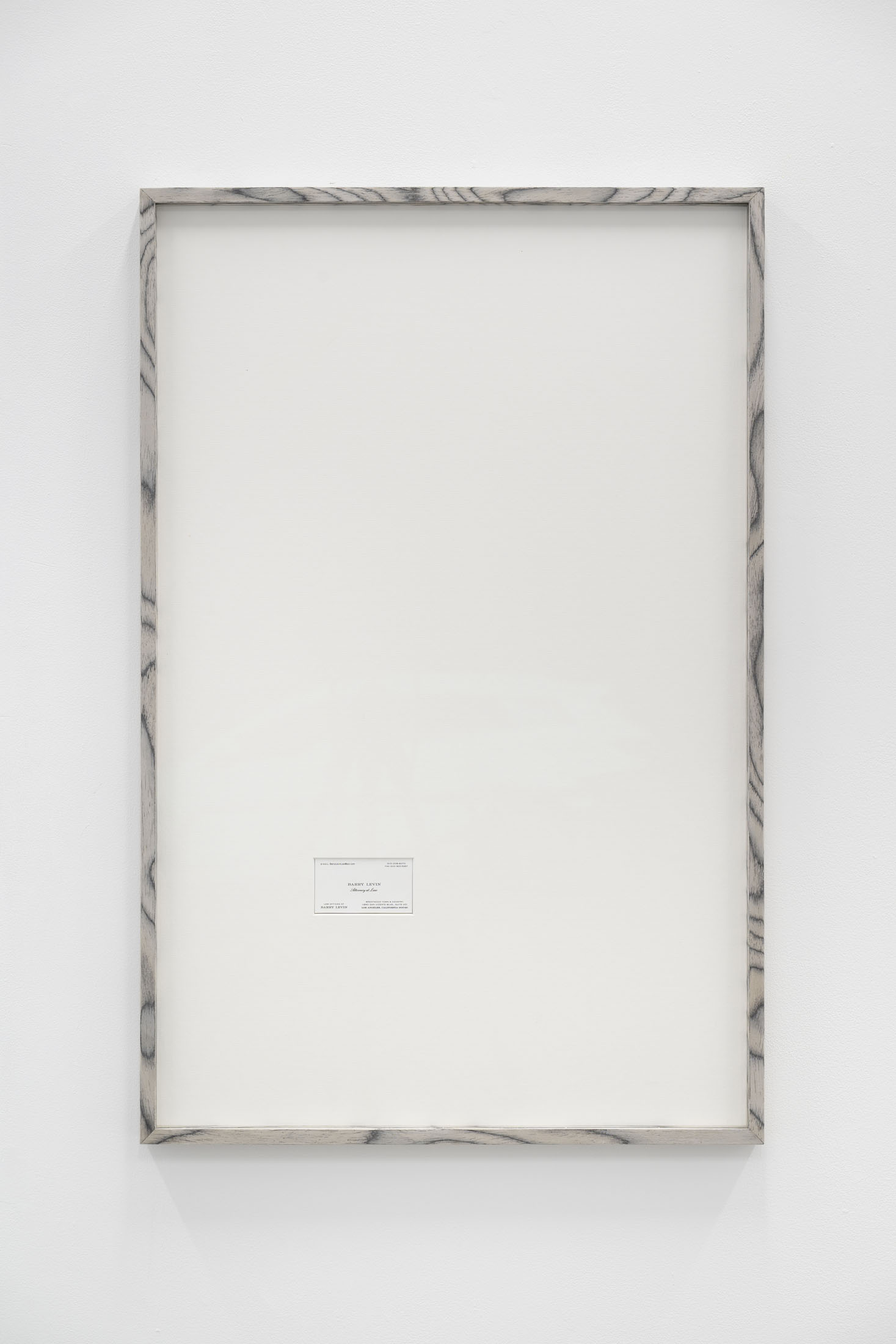

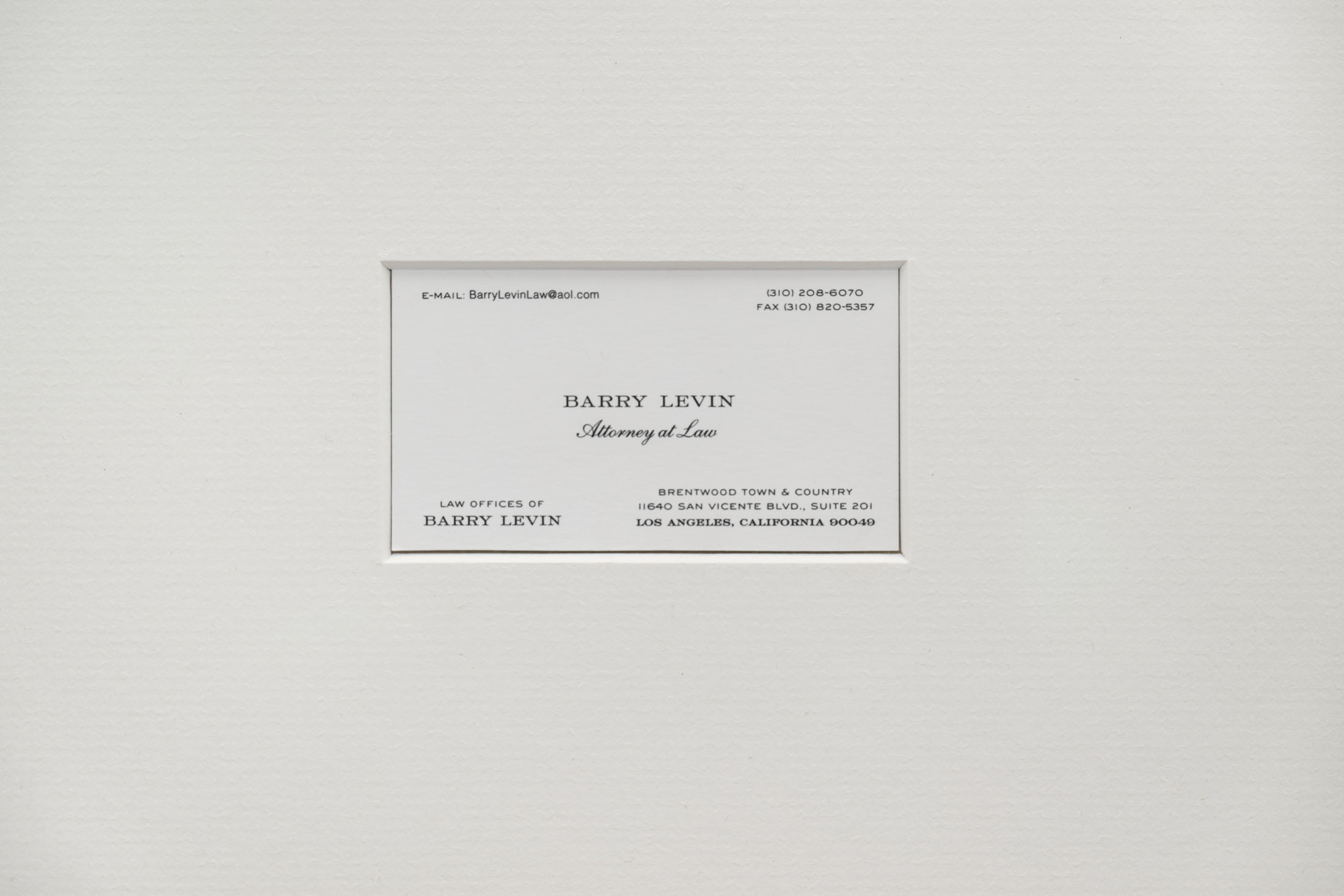

Slinger also collects bizarre cards — obsessively, to the point of debt. Not Pokémon, not Magic or One Piece, but memorabilia where George W. Bush often appears in the background. The goofy Texan becomes a soft-focus icon of the Axis of Evil: Iran, Iraq, North Korea. A neoconservative slogan, rebranded as pop culture. Most of their collection centers on modern American politics, and more specifically the Gulf War — the first war of images, where real bloodshed was hidden behind the flicker of screens and the obscene choreography of media coverage. As Jean Baudrillard argued in The Gulf War Did Not Take Place, the conflict was justified by lies and illustrated by images whose reality could not be verified. Slinger, in a postmodern lineage, collects images of the Menendez brothers at liberty — as if archiving fragments of narrative ambiguity. Here, it’s a basketball card. It says nothing. It’s not about truth — it’s about absorbing the grand narratives. Are they innocent teens enjoying a championship? Or dangerous criminals savoring their final moments of freedom?

That ambiguity is exactly what Slinger seeks: a fixation on the hyper-mediated face of transgression. They don’t collect evidence — they collect surfaces. They’re not interested in history — but in what stories can be told. These could be cards of Justin and Hailey Bieber, Kim and Kanye, Taylor Swift and Travis Kelce, Rihanna and Travis Scott. But Slinger chooses something else: demonic twinks, possessed bodybuilders, incestuous angels of Beverly Hills, patricidal orphans in Ralph Lauren polos. The ones from The Monster.

Slinger doesn’t represent these instruments of control — they handle them. They distort them. They embody them. Because their work is fed by memory. Their own.

In another time, they might have been called a victim of black pedagogy — corporal punishment, mental manipulation, ritualized humiliation. “Spare the rod, spoil the child” — the founding dogma of a toxic educational tradition.

Benjamin Slinger doesn’t try to represent trauma. They give it texture. Make it tactile. Collectible. They put it into plush. They suspend it from ropes. They seal it inside glossy cardboard. Their work is neither catharsis nor critique. It is compulsion, repetition, the raw materiality of the symptom.

In that sense, their practice echoes the post-Pictures Generation — strategies of citation, reproduction, and accumulation. There’s something of Peter Nagy’s Nature Morte gallery here: self-referential aesthetics, fetishistic displays of dead objects oversaturated with signifiers. Anglo-American, late ’80s, somewhere between decadent New York and post-punk London. Yuppie sadomasochism. Perverse materialism. An elegy to toxic consumption.

Slinger doesn’t make installations — they compose nervous altars, haunted still lifes, where every object contaminates the next. The plush infects the Regency lamp. The IKEA drawer becomes an echo chamber for the shame mask. The collector cards aren’t nostalgic — they’re compulsive relics, archives of media violence, pop trauma rebranded as product. This is an art of aftershock. Of endless reverberation. A practice shaped by trauma — but also by a razor-sharp awareness of the culture industry’s power to digest crime, package rape, brand suffering. Where others seek healing or sublimation, Slinger piles up, displays, repeats — like a child compulsively replaying a scene of panic with their toys, again and again.

In the end, their exhibition reminded me of that faux-fur Furby backpack I once saw in rehab, slung over the shoulders of a morbidly obese woman who only ate applesauce. Ingested sweetness. Unmanageable childhood.