Artist: Benedikte Bjerre

Exhibition title: Sex and the city

Venue: palace enterprise, Copenhagen, Denmark

Date:December 14, 2023 – February 10, 2024

Photography: all images copyright and courtesy of the artist and palace enterprise, Copenhagen

Modernist aesthetic is not what one might call lush or fertile. There are no elaborate acanthus leaves on Brancusi’s Column, and Mies van der Rohe’s Barcelona pavilion, with its inhuman perfection, its fetishism of stone, steel and glass, appears so barren, if it has any relationship to sex it is strictly to the world of BDSM, a variety, which, ironically, has little to do with form following function.

This curious absence in (high) modernism of bodiliness, flesh or sex, not to mention its oddly repressed outcome – childrearing – screams to the heavens, demanding to be somehow compensated. That, anyway, is how I’ve tended to read the striking presence in the Barcelona pavilion of Georg Kolbe’s nude female form, the only indexical figure on site. And also Lewis Morley’s iconic 1963 photograph of a naked Christine Keeler covering her privates behind the backrest of a knock-off of Arne Jacobsen’s 7. This pose was since copied many times over, for instance by the Spice Girls in the live performance of their song Naked. One chair, five chicks: the implication of the body is as crucial as its absence.

Another image comes to mind: a 1968 cover of Alt for Damerne featuring a different Jacobsen classic, The Egg, inside which are four children showcasing the washed-and-combed centre of Ideology. There is something unintentionally vulgar about how this image takes Jacobsen’s purely formal reference to sexual reproduction and lets function follow; how the children sit like yolks inside the egg, manifesting the life that the chair’s triumphantly reduced “organic” form was supposed to keep from view.

This is where Benedikte Bjerre’s exhibition begins: at the possibility of vulgarity; that something simple might also be in excess. Her large shiny Easter eggs recall both modernist slickness as well as what it has repressed: the farcical image of fertility in capitalism, the gross industrialisation of desire, our total alienation from sex and subsequent abstraction of its possible, ehm, material effects. As they lie there, they appear as far from the reality of sexual reproduction as Jacobsen’s Egg, the distance between a horse and a car, a great glass pane and a dessert of sand. And yet, they elicit want – this is where sex nonetheless rears its head. You want to consume them, you want to be them, your pupils take their shape. The egg represents the oxymoron of objectified desire; life in its most hollow form as commodity. The Kinder Surprise is the gift that keeps on giving, a Russian doll. In an act of perverse tautology we give them to children, so that they can receive the surprise of themselves as gift, a plastic proxy. To adults, the egg arrives as sex toy, stirring with life, to be reintroduced into the body’s various orifices as a reversion of birth that allows its repetition as pure form.

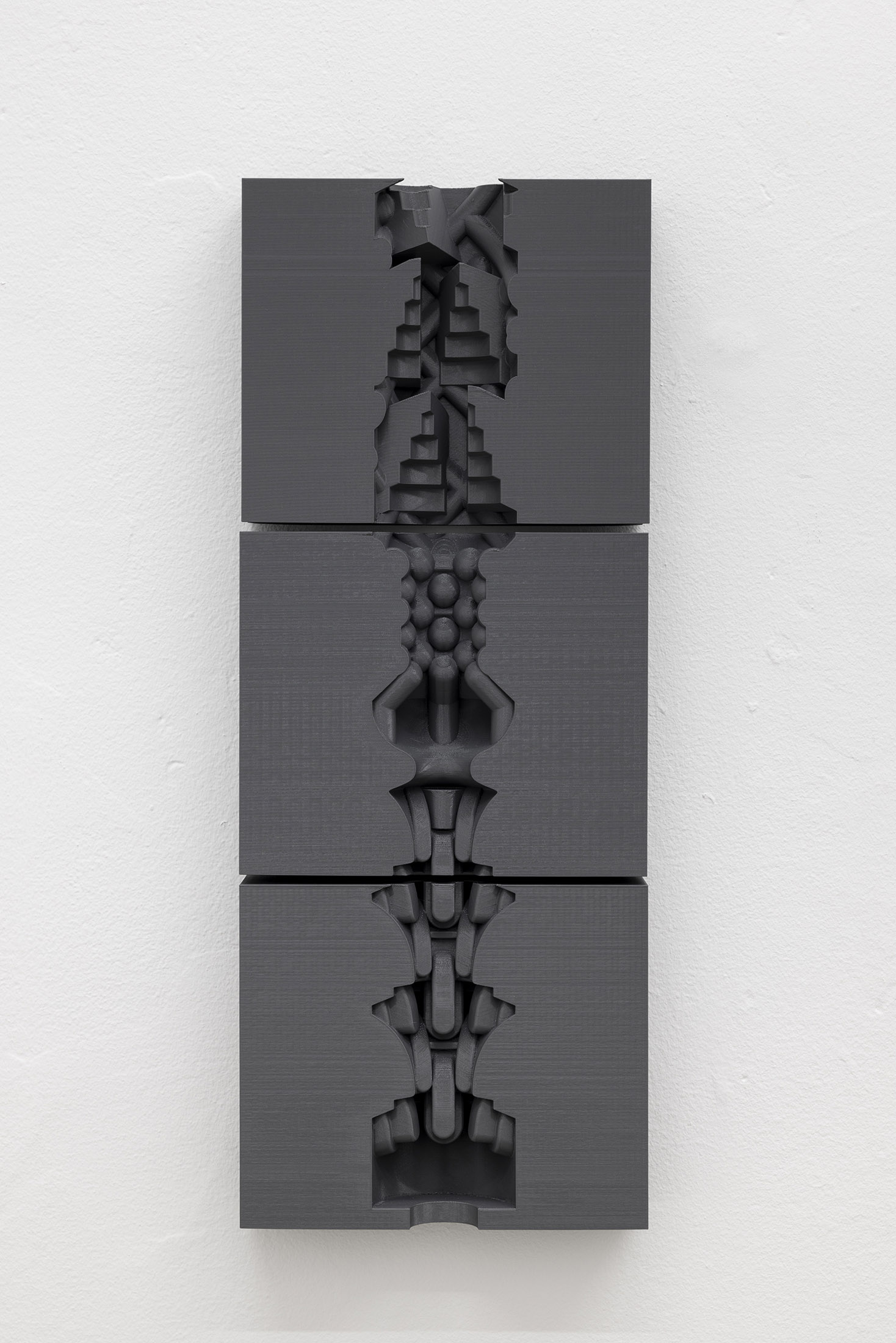

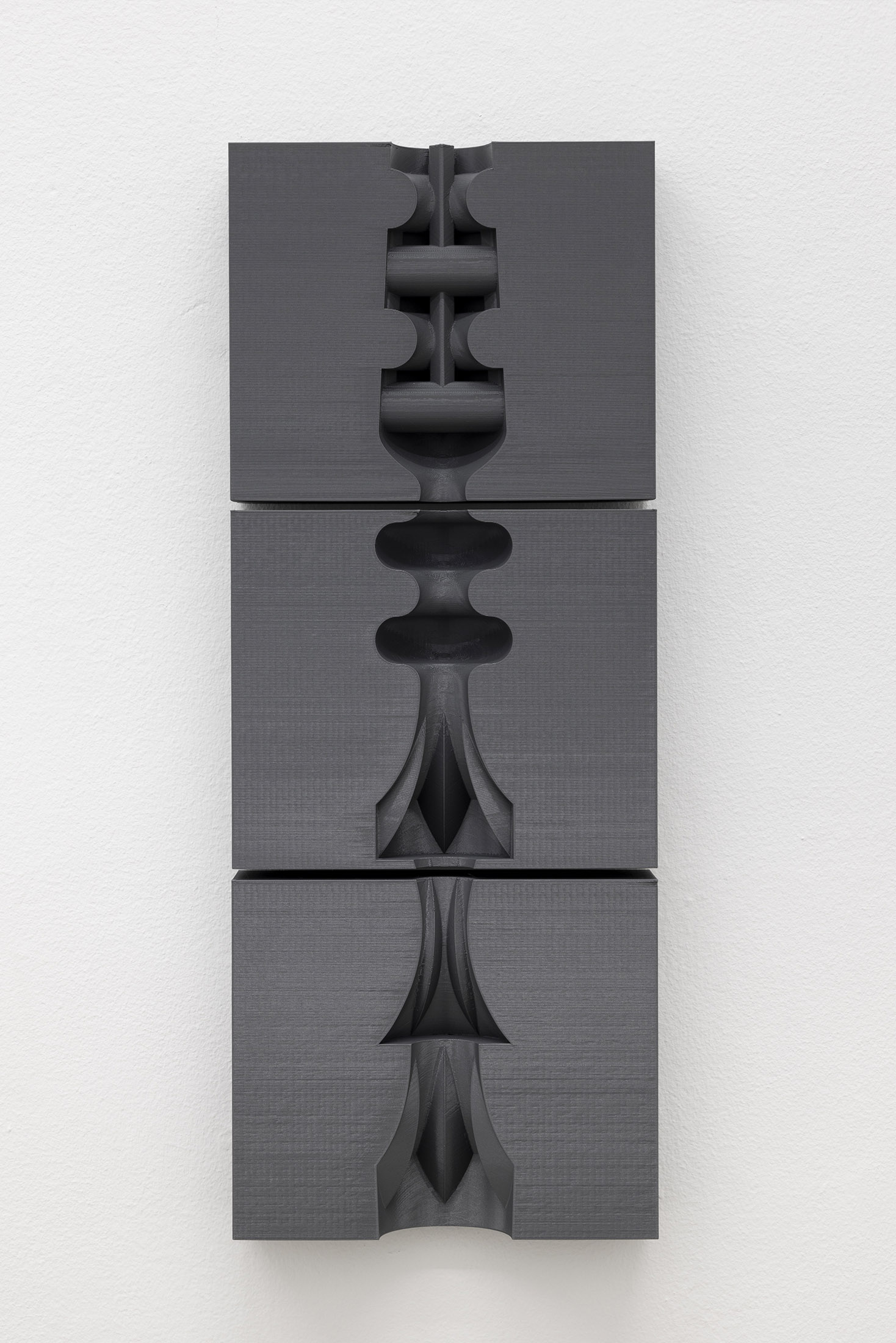

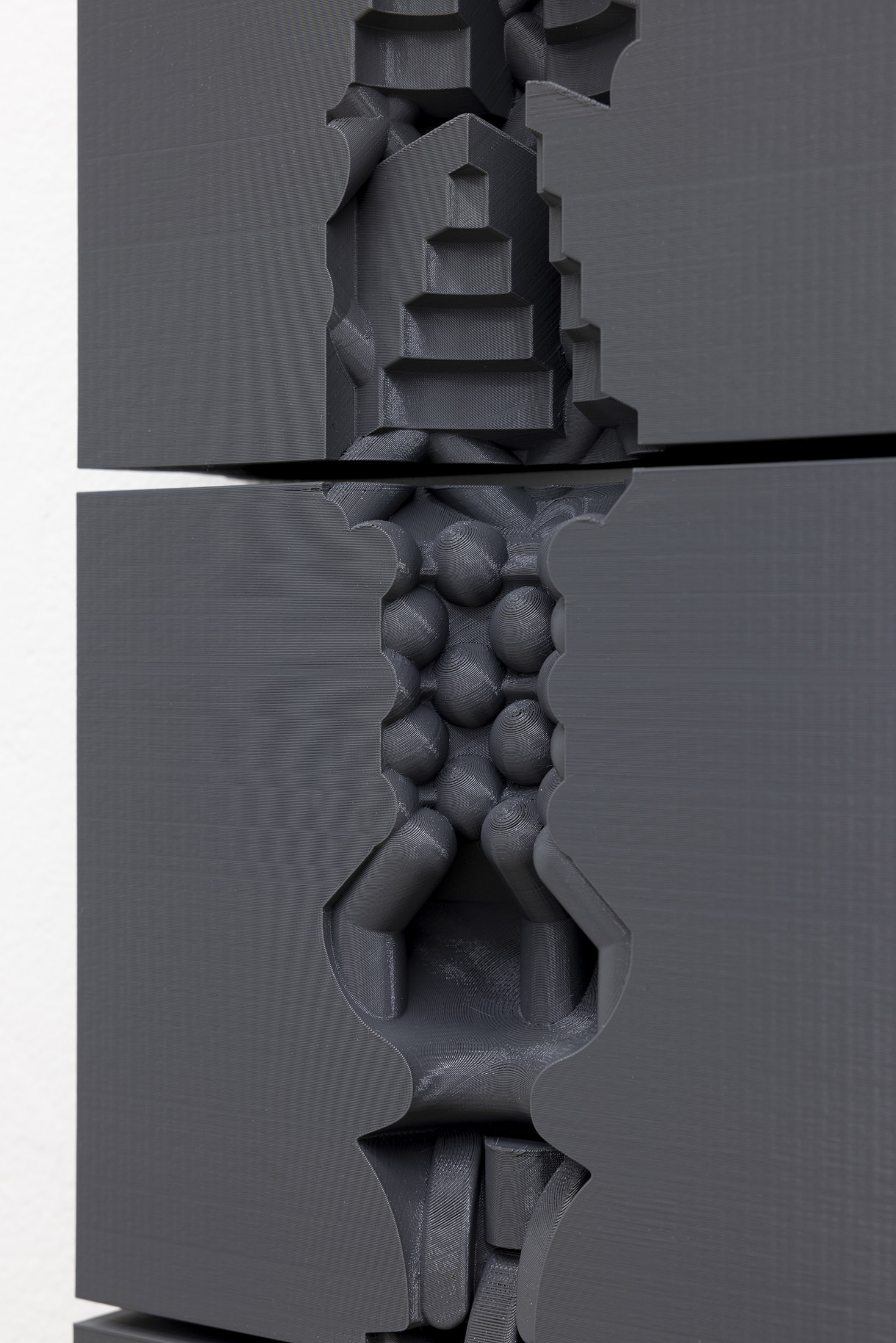

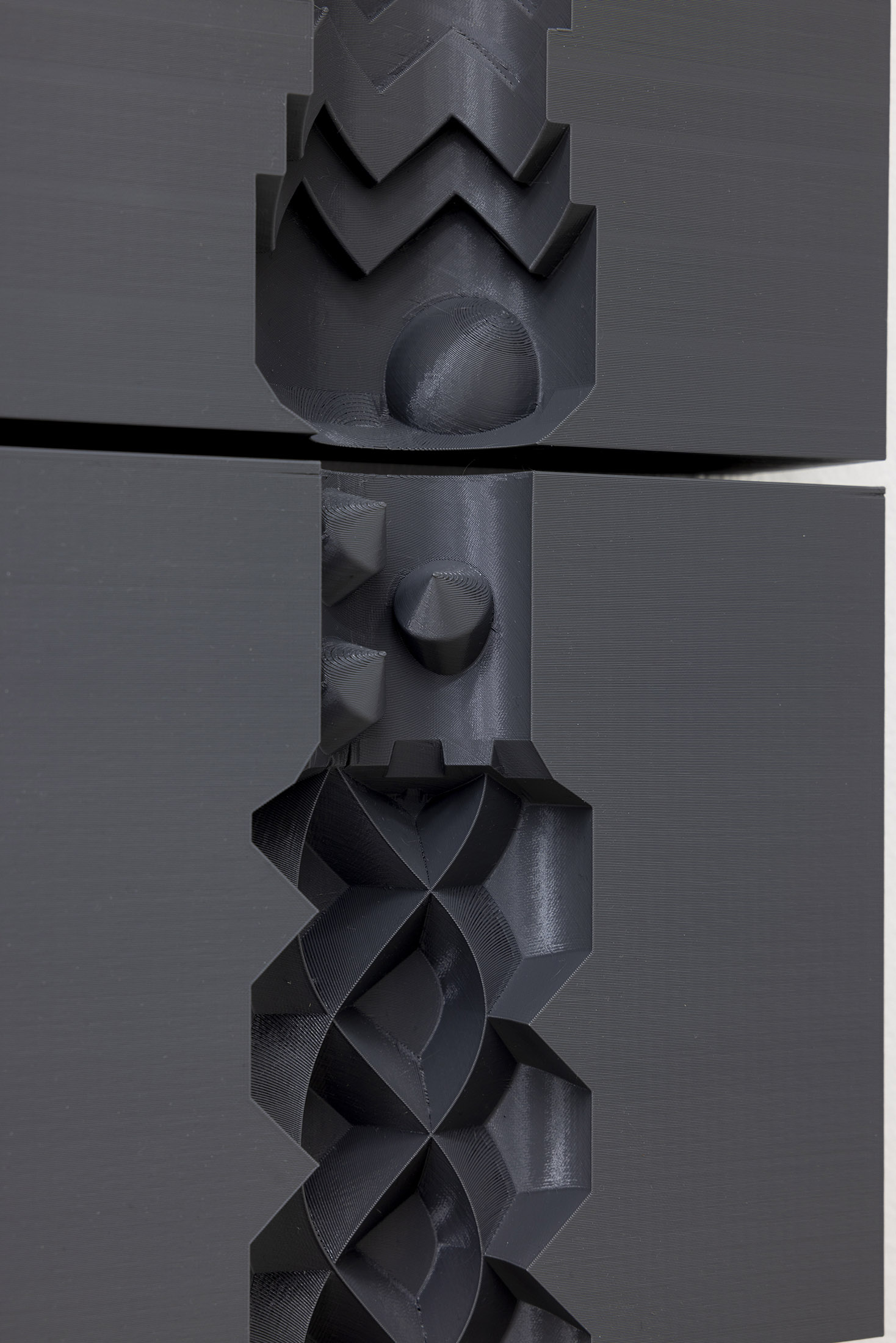

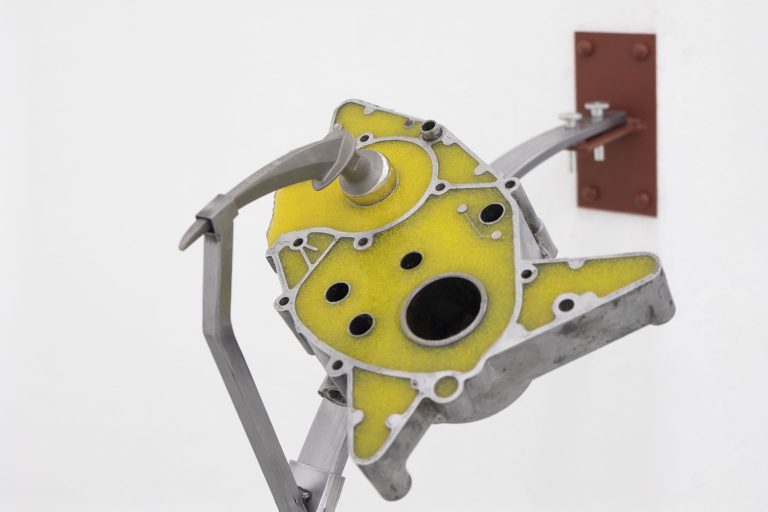

Certain of the penile masturbation devices known as fleshlights claim to take the shape of this or that pornstar’s vaginal interior. This shape, as it is rendered on the package, brims with the authority of science and technology. It looks like the mould for some elaborate piece of engineering, a Zaha Hadid building, or, indeed, a sculpture by Brancusi. In this teched-out vulva, we might say, both winkingly and in earnest, we find the legacy of the Bauhaus. Bjerre has titled both the eggs and the fleshlight reliefs after Brancusi – Nearly Newborn and The Column – as if to bring some of the banality that is allowed to rise to the surface of her work to bear on the famed simplicity of that artist, and perhaps on modernism more generally. The relationship between the two works is that there is none, by which I mean: there ought to have been, naturally, since both belong to the world of “flowers and bees”, but we’ll arrive at it here only intellectually, through the alienated language of formal abstraction.

And yet, vulgarity sits inside the work like a toy inside a chocolate egg. When Bjerre leans on modernist aesthetics it is with a fairly sober understanding that the New only comes as a surprise once; that stylistic progression is a form of death drive; that modernist heroics is but the last great gasp of romantic pretensions to genius. But it is possible, too, I think, to read the measured cool of Bjerre’s sculptures, their abstention from beauty, as an at once humorous and dead serious rescue mission for some of what modernism made possible: detachment, formality, integrity, a reflexive intelligence. As such, we might say, she puts the language of modernism in scare quotes and uses it as a Kinder Surprise for its best ideas.

By Kristian Vistrup Madsen, Art critic, curator and writer