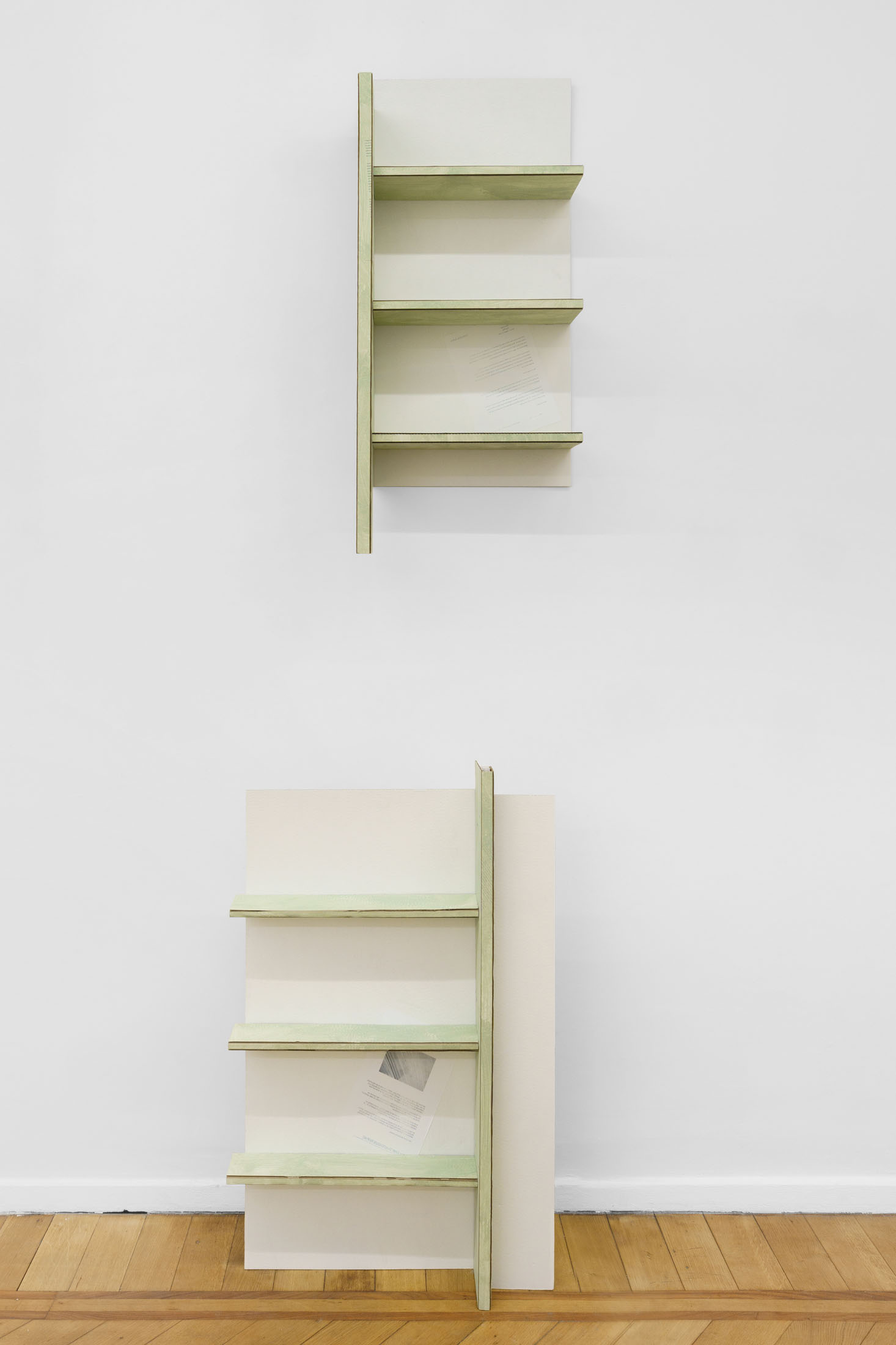

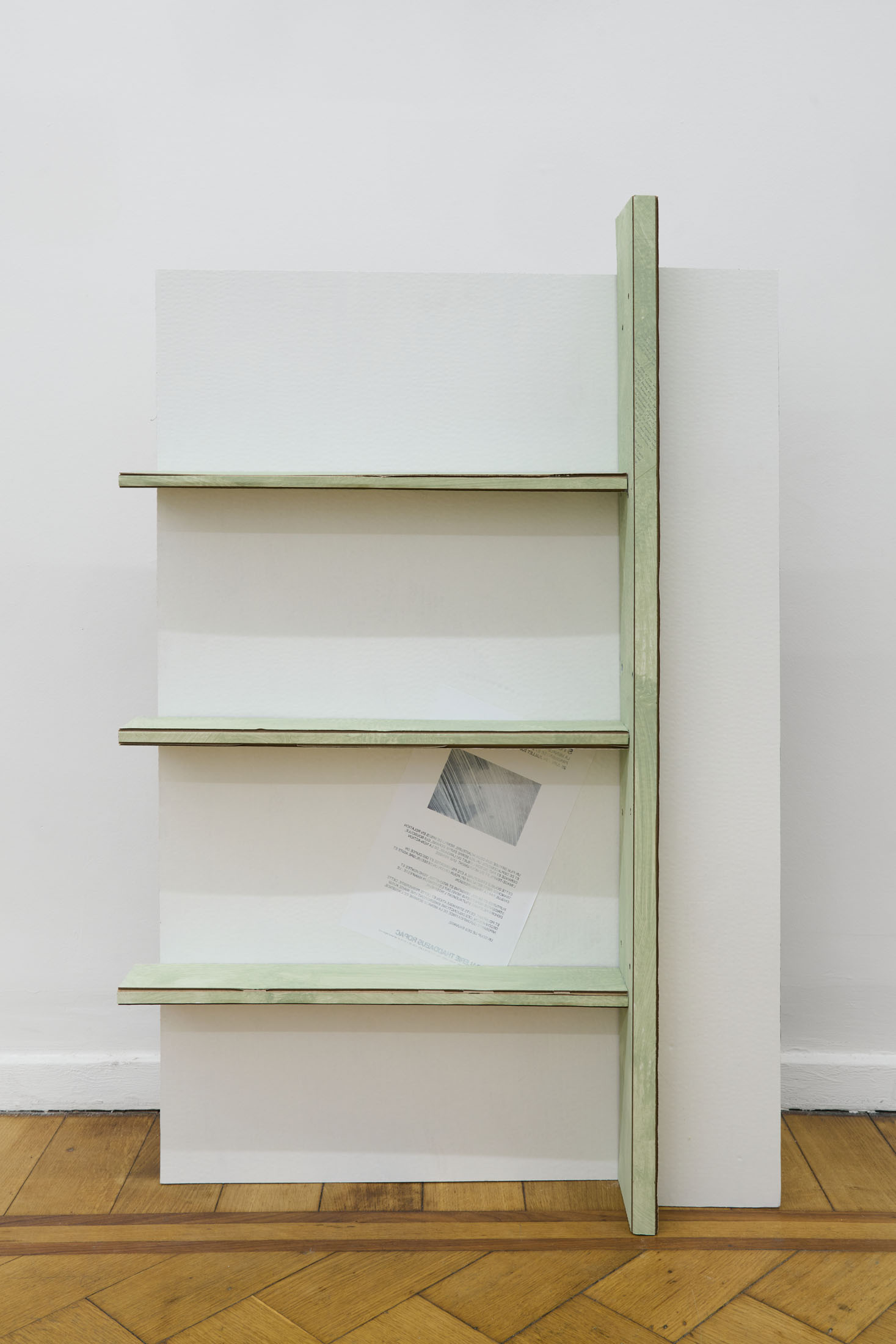

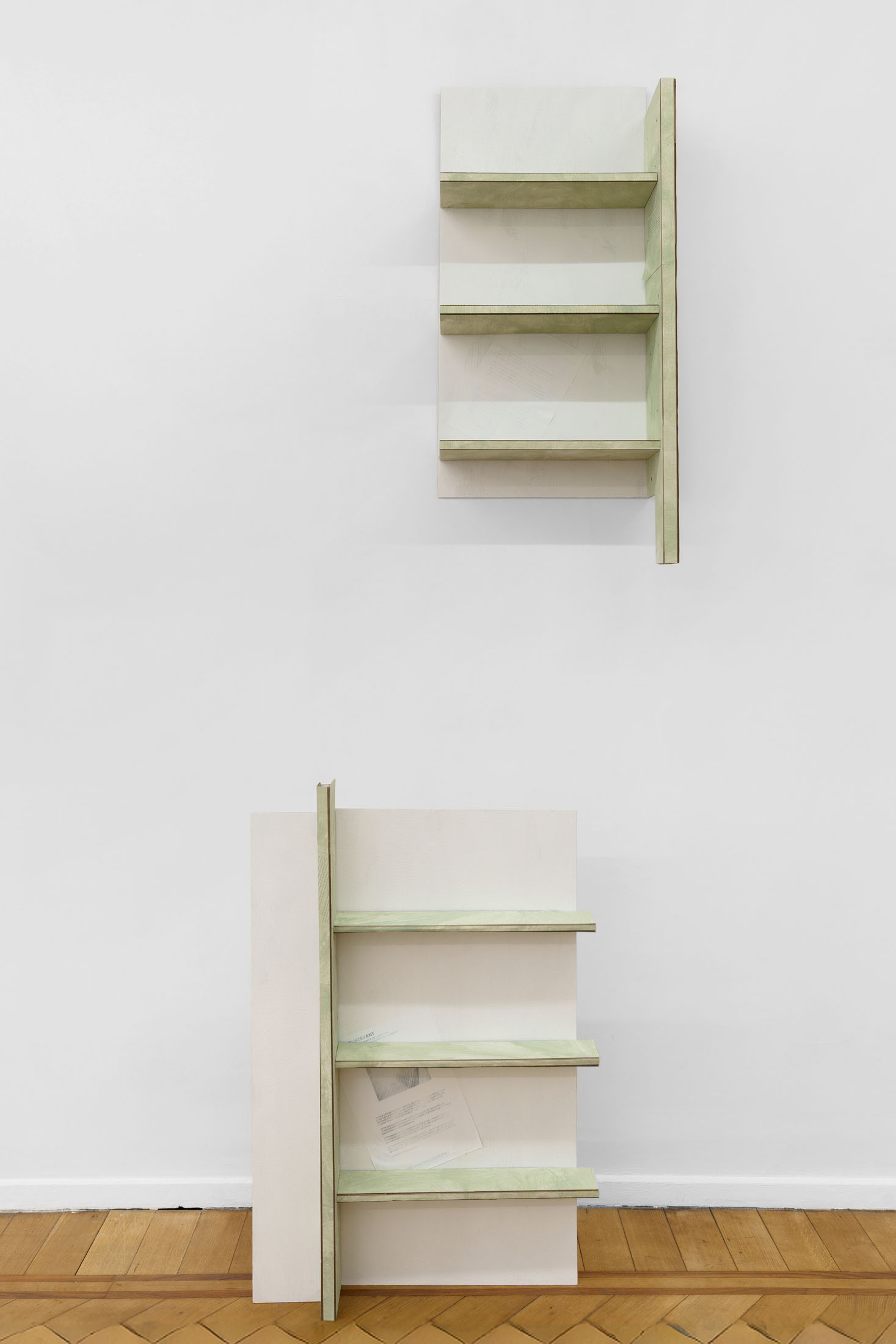

When a single actor plays a pair of identical twins, clones, doppelgängers, etc., cinematographers use a technique called the “twinning effect” to make them appear twice (or more) within the same frame. When twinning happens to the gallery space itself, it becomes easy to fall into the mirror’s trap: the gallery, the work, refers only to itself or its image, back and forth eternally:

A1 ←→∞ A2

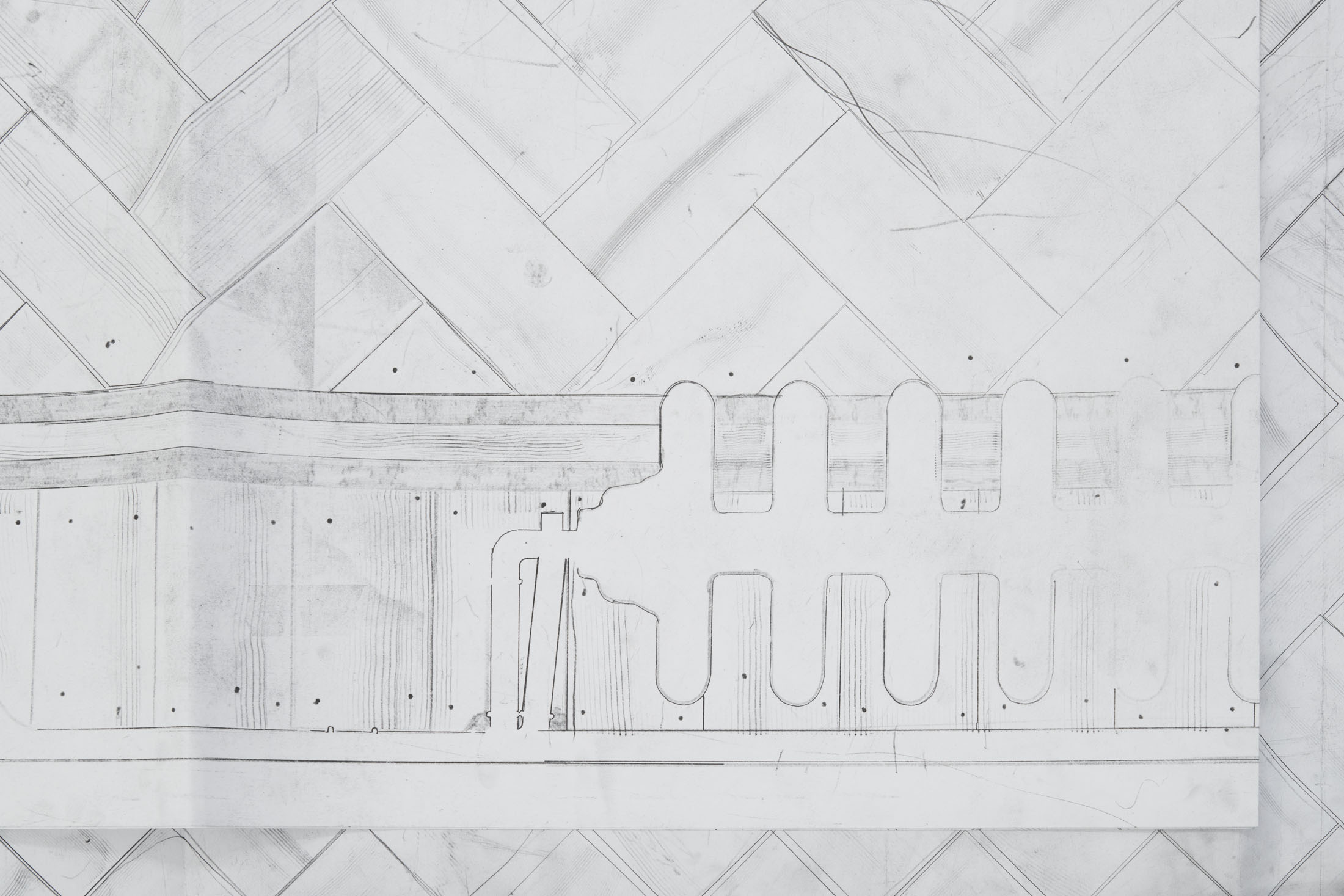

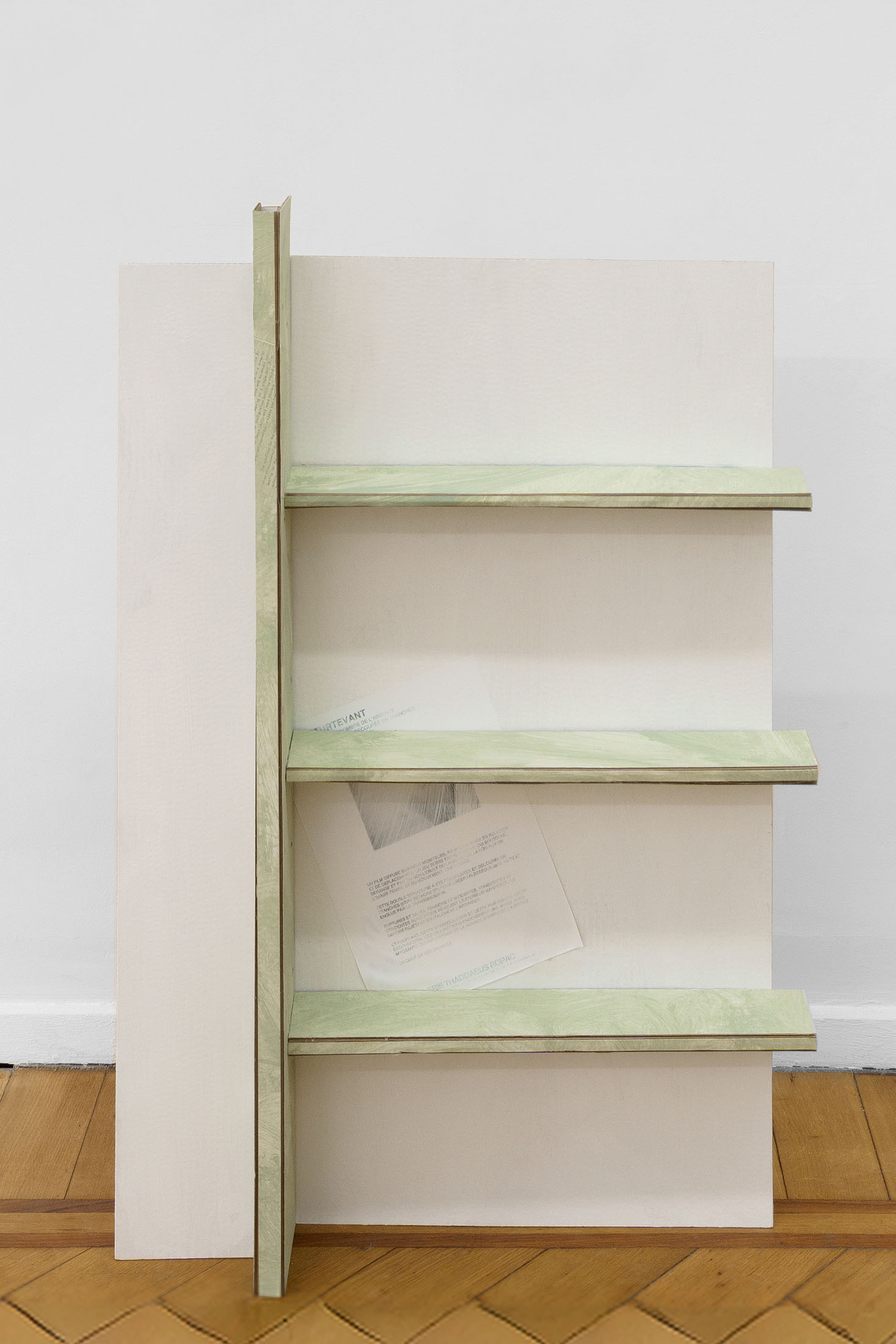

My only option, then, was to approach the exhibition as a true experiment: to follow through and see what is produced, without prior goals. I noticed, when mirroring the floor plan of the space, that the resulting diagram produced a gap in the negative space near where the twinned galleries met. I allowed this third space to be my guide.

Two-way glass is a kind of mirror where one side is reflective, while the other side appears transparent, like a window. Testing whether a mirror is two-way or not is simple: place a finger on the glass, and if a gap appears between the fingertip and its reflection, it is a standard mirror:

→||←

The gap is the thickness of the mirror itself. In a two-way glass, the reflective coating is on the surface, so the real and the imaginary finger appear to touch, without a gap in between:

→|←

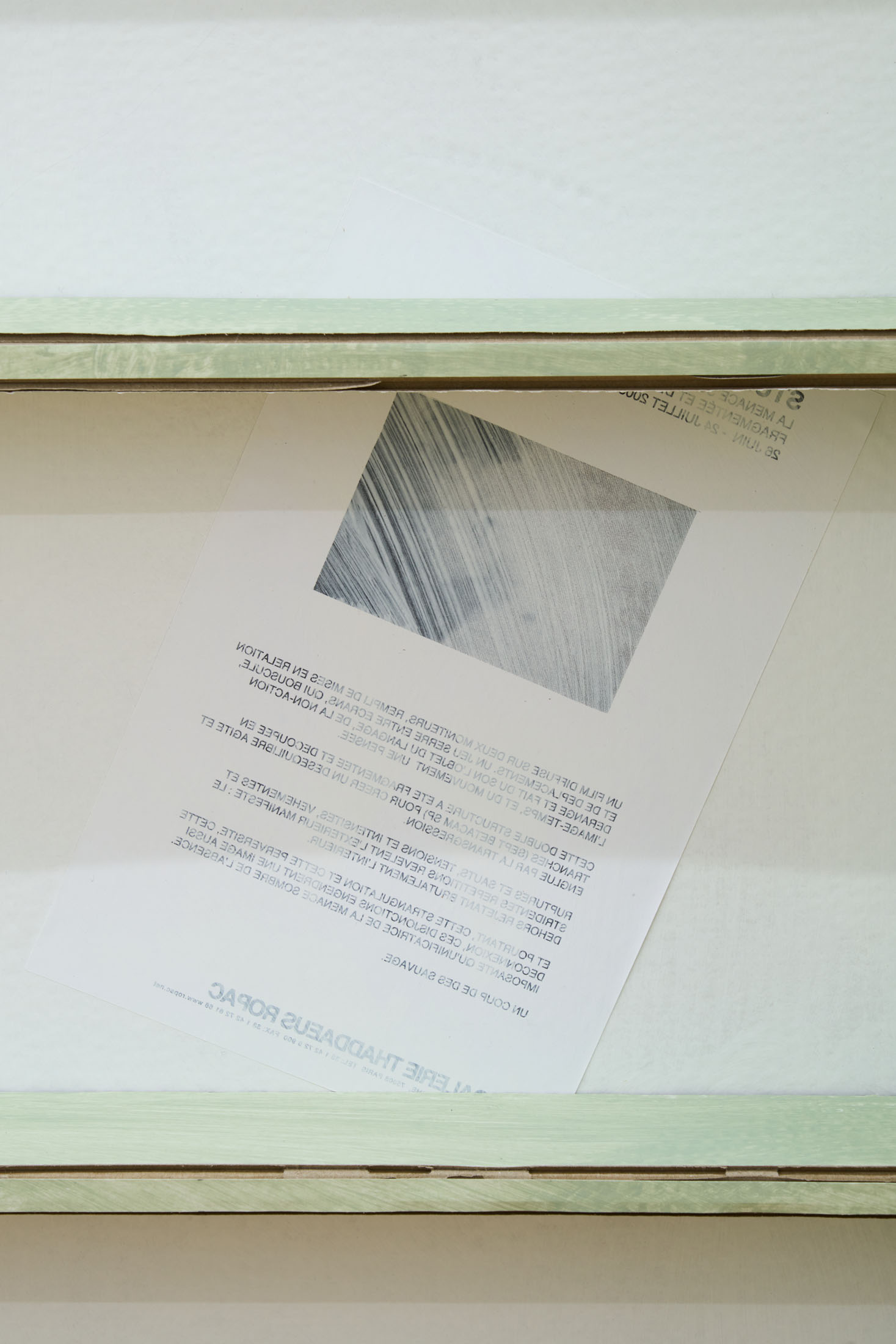

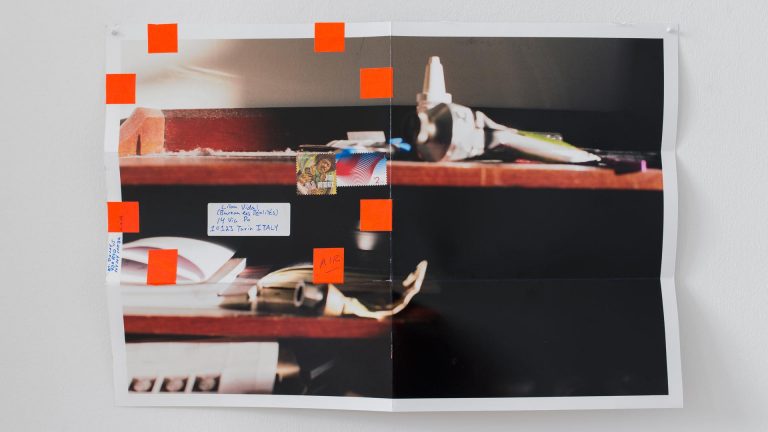

The meeting point of these two fingers is the location where a pleat is sewn. The specific lack of a gap between the fingers is precisely what signifies that there is a seam, a closure in the field of vision that conceals a pocket. There are no two-way mirrors in this exhibition, but there is a seam.

The artists in this exhibition, Fiona Connor, Ima-Abasi Okon, Pol Wah Tse and myself, were asked to work on both sides of the glass, both as a lens, a surface, and a hinge. These works in various ways span the distance between the two sides of the reflection. They throw something out, and reel it back in again, to test the gap: here, gone, fort, da.

– Becket MWN