Artist: Bea Schlingelhoff

Exhibition title: No River to Cross

Venue: Kunstverein München, Munich, Germany

Date: September 11 – November 21, 2021

Photography: All images copyright and courtesy of the artist and © Kunstverein München

Note: Exhibition booklet is available here

In her artistic practice spanning more than twenty years, Bea Schlingelhoff works to remember women’s forgotten biographies and to dissolve patriarchal frameworks, as well as tracing the persistence of fascist structures. A central aspect of her practice is the intuitive engagement with the history of the respective exhibition sites, making their socio-political (power) structures intelligible. Her works are interrogations of the ideology and history of a location and are thereby suffused with an awareness of her own dependence on the conditions of the respective working context. The artist, whose work also includes drawing, sculpture, and typography, discloses these structures through site-specific interventions: additions, changes, and subtractions on architectural as well as structural levels. By shifting the relationships between these levels, she reveals inherited notions of how spatial and juridical arrangements are structured. Formally, this often occupies an incisive, intermediate position between the classical concept of the work and display.

For her solo exhibition No River to Cross at the Kunstverein München, Schlingelhoff deals with the institutional structure as well as the Nazi history of the Kunstverein and that of its current site. The departure point here is, on the one hand, the Kunstverein’s complicity with the Nazi regime and its violent agenda of Gleichschaltung and the ethno-nationalist realignment of German cultural politics from 1933 onward, as well as the exhibition “Entartete Kunst” (Degenerate Art) which took place in 1937 and was partly held in the Kunstverein’s current building, albeit before the institution moved in in 1953. On the other hand, the long-term interventions in (institutional) structures that are characteristic of Schlingelhoff’s practice take the form of a proposal to amend the institution’s charter. Through this, Schlingelhoff investigates the question of individual artistic agency vis-à-vis institutional structures.

Based on the research in the Kunstverein and Munich City Archives, the artist developed a proposal to add a preamble to the Kunstverein’s charter.1 This proposal includes an apology from the Kunstverein München concerning its cooperation with National Socialists, and the inclusion in its charter of a paragraph passed at the 1936 general meeting2 that stated that “non-Aryans cannot become members of the association.”3 Furthermore, the proposed preamble includes an acknowledgement of the joint responsibility for the injustices committed by the Reich Chamber of Culture and the Reich Chamber of Fine Arts, as well as a lasting commitment to the principles of non-discrimination and equality. Schlingelhoff’s proposal to amend the bylaws was submitted to a vote by the Kunstverein’s nearly 1,300 members at an extraordinary assembly on August 19, 2021, where it was passed on a majority vote. This result was documented and can be seen as part of the exhibition alongside a number of other documents. The artist thus draws on the Kunstverein’s membership structure—with effects that last beyond the exhibition’s duration—and makes its democratic mechanisms and legal constitution part of her work.

Since 2016, each of Schlingelhoff’s exhibition has been accompanied by a document drafted by the artist. This involves a negotiation between the artist and the exhibition venue’s representatives about the conditions under which art is to be shown. The artist requests amendments from such institutional or commercial venues, which are included in the document as handwritten notes. If an agreement is reached between, the document is formally accepted by the signature of all parties and visibly displayed in the exhibition venue. If there is no consensus, the document is exhibited unsigned.

Prior to the exhibition No River to Cross, director Maurin Dietrich and curator Gloria Hasnay were handed a letter of apology drafted by the artist, in which they as representatives of the Kunstverein apologize, among other things, for the collaboration with the Nazi regime.

Schlingelhoff asked them to revise the letter composed in German and English. The two documents, including the marked corrections, are featured in the exhibition. Both the letter and the charter amendment negotiate apology as a political action that always involves the question of which entity can actually carry out or be responsible for this speech act. It also negotiates the question as to what the legal consequences and implications of an apology are beyond the symbolic political act.

An art institution is defined by a complex interplay of numerous elements, some of which change constantly. It is not only the personnel and, consequently, the program’s direction that are in a continuous state of flux. An institution’s economic (co-)dependencies, internal and external socio-political dynamics, and educational and academic tasks are also continually evolving. As one of many elements, its architecture plays a minor yet crucial role: it is the institution’s most prominent aspect, providing the actual space in which everything else unfolds. So what happens to the memories inscribed in this architecture when spaces change their function and are reoccupied?

After the National Socialists seized power in 1933, numerous German museums were robbed of their works of Modern art and progressive directors stripped of their office in the course of the fascist purges. One day after the opening of the “Haus der Deutschen Kunst,” on July 19, 1937, the punitive exhibition “Entartete Kunst” opened in the immediate vicinity in Munich’s Hofgarten arcades. The exhibition brought together over 600 works of art that had been confiscated from 32 German museums. Whereas the works in the “Große Deutsche Kunstausstellung” (Great German Art Exhibition) at the Haus der Kunst were conservatively and monumentally staged in line with the National Socialist’s propagandist view of art, early Modernist works were chaotically presented at the Hofgarten, displayed close together, surrounded by derisive commentary, and stigmatized. The exhibition was adapted and toured twelve other cities in Germany and Austria until 1941—by then around 17,000 works of art had been confiscated from more than 100 museums.4

By painting the walls in color, Schlingelhoff has mapped out the original presentation of the artworks categorized as “degenerate” by the National Socialists that hung in the Kunstverein’s current premises. The works’ sizes and approximate placements are recreated, occupying the Kunstverein’s walls with a ghostly presence.5 The superimposition of a site’s history and present at different times offers the artists defamed by the National Socialists and their works a new, different space and thus becomes a method of remembrance.

The building that now houses the Kunstverein consists of several layers: even though it suggests a historical reality, it does not necessarily honor that promise. It is a loose reconstruction of the building, which was largely destroyed in the Second World War; the current structure of the pseudo-classical building mainly dates from the 1950s. Architectural reconstructions, such as that of the Hofgarten arcades, are at times retrogressive and always harbor a certain negation of history. Accordingly, they can be understood as a built statement against memory (and, in a broader sense, against apology). Within the cartographic recreation of the “Entartete Kunst” exhibition, the superimposition of both historical and contemporary premises highlights incongruences, thus becoming an analysis of historiography itself.

For several years, Bea Schlingelhoff has been reflecting on fascist and patriarchal writings of history in her artistic practice. She not only analyzes them methodically, but also takes writing itself as a starting point. Thus, the typefaces she dedicates to politically and culturally engaged women are central to her work. Accordingly, individual typefaces from her series Women against Hitler (2017–present) bear the names of forgotten or occasionally murdered resistance fighters: Marianne Baum, Lisa Fittko, Elise Hampel, Anne-Marie Im Hof-Piguet, Anna Mettbach, Hanna Solf, and Ella Trebe. The typefaces designed by Schlingelhoff are available for free download during their respective exhibition durations and seek to update or rewrite history with a new awareness. In other words, the artist intervenes in the very infrastructure of communication, creating the space for a conceptual and literal (re)formulation of history. In line with this approach, Schlingelhoff has installed four small signs in No River to Cross naming the only female artists of the “Entartete Kunst” exhibition in Munich: Maria Caspar-Filser, Jacoba van Heemskerck, Marg Moll, and Emy Roeder. They are set in the typeface Marianne Baum, designed by Schlingelhoff. The signs remain permanently installed, bringing non-canonized female positions (back) into the field of view. Moreover, the signs assume the function of a commemorative sign in public space that has so far not been realized on the part of the city.

Schlingelhoff’s works are both deconstructions and systemic critiques: with the different parts of the exhibition—namely, the history of the institution and its locality—the artist makes the gaps in the Kunstverein’s engagement with its own history legible as well as those in the collective memory of a city and its society. Furthermore, Schlingelhoff creates concrete and structural lieux de mémoire (realms of memory),6 tangible points of reference where remembrance can be activated, restored, recorded, and edited, and thus (re)incorporated into a collective memory.

1A preamble is a preface to laws, international agreements, or treaties. It usually presents the motives, intentions, and basic convictions of its authors.

2 As with all other Kunstvereine in Germany, the Kunstverein München had its license revoked after the Second World War. Since its first reassembly in April 1947, the 1936 paragraph is no longer in the bylaws.

3 See the Kunstverein München e.V. inventory held at the Monacensia Library.

4See the database of the “Entartete Kunst” Research Center at the Art History Department of Freie Universität Berlin. This database holds a complete list of the “degenerate art” works confiscated from German museums between 1937 and 1938. Online: https://www.geschkult.fu-berlin.de/en/e/db_entart_kunst/index.html.

5 The partial artistic reconstruction of the Entartete Kunst exhibition is based on various sources, including the book Stephanie Barron (ed.), Degenerate Art: The Fate of the Avant-Garde in Nazi Germany, Los Angeles, 1991; the scale model reconstruction from the eponymous 1991 exhibition at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA); and historical photographs from the Munich City Archives (DE -1992-FS-NS). As an artistic rather than scientific work, Schlingelhoff’s partial reconstruction is not intended to be exhaustive.

6The term was coined by French historian Pierre Nora in the 1980s. The concept of “realm” or “place” is to be understood in both concrete and metaphorical senses.

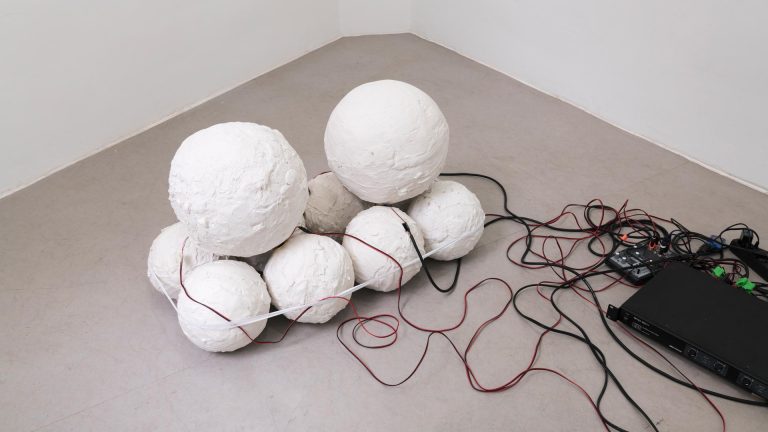

Installation view: Bea Schlingelhoff, No River to Cross, Open Letter, 2021. Courtesy the artist and Kunstverein München e.V.; photo: Constanza Meléndez

Installation view: Bea Schlingelhoff, No River to Cross, Open Letter, 2021. Courtesy the artist and Kunstverein München e.V.; photo: Constanza Meléndez

Installation view: Bea Schlingelhoff, No River to Cross, Open Letter, 2021. Courtesy the artist and Kunstverein München e.V.; photo: Constanza Meléndez

Installation view: Bea Schlingelhoff, No River to Cross, Open Letter, 2021. Courtesy the artist and Kunstverein München e.V.; photo: Constanza Meléndez

Installation view: Bea Schlingelhoff, No River to Cross, Open Letter, 2021. Courtesy the artist and Kunstverein München e.V.; photo: Constanza Meléndez

Installation view: Bea Schlingelhoff, No River to Cross, Open Letter, 2021. Courtesy the artist and Kunstverein München e.V.; photo: Constanza Meléndez

Installation view: Bea Schlingelhoff, No River to Cross, Open Letter, 2021. Courtesy the artist and Kunstverein München e.V.; photo: Constanza Meléndez

Installation view: Bea Schlingelhoff, No River to Cross, Open Letter, 2021. Courtesy the artist and Kunstverein München e.V.; photo: Constanza Meléndez

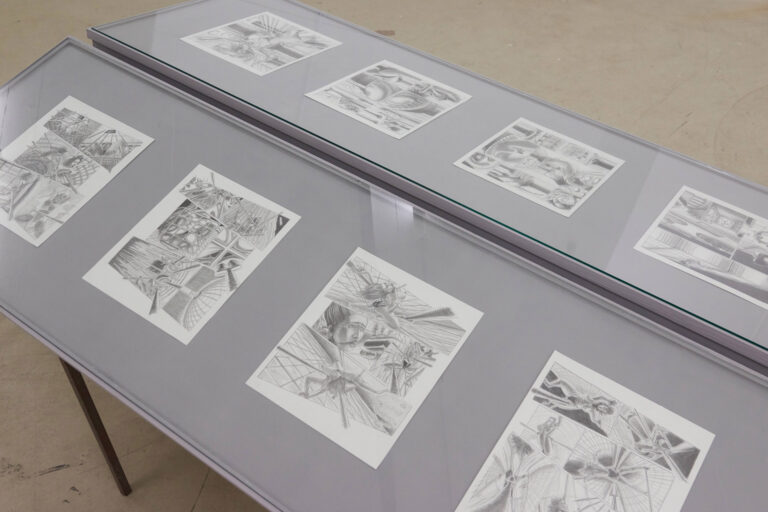

Installation view: Bea Schlingelhoff, No River to Cross, Mapping, 2021. Courtesy the artist and Kunstverein München e.V.; photo: Constanza Meléndez

Installation view: Bea Schlingelhoff, No River to Cross, Mapping, 2021. Courtesy the artist and Kunstverein München e.V.; photo: Constanza Meléndez

Installation view: Bea Schlingelhoff, No River to Cross, Mapping, 2021. Courtesy the artist and Kunstverein München e.V.; photo: Constanza Meléndez

Installation view: Bea Schlingelhoff, No River to Cross, Mapping, 2021. Courtesy the artist and Kunstverein München e.V.; photo: Constanza Meléndez

Installation view: Bea Schlingelhoff, No River to Cross, Mapping, 2021. Courtesy the artist and Kunstverein München e.V.; photo: Constanza Meléndez

Installation view: Bea Schlingelhoff, No River to Cross, Mapping, 2021. Courtesy the artist and Kunstverein München e.V.; photo: Constanza Meléndez

Installation view: Bea Schlingelhoff, No River to Cross, Mapping, 2021. Courtesy the artist and Kunstverein München e.V.; photo: Constanza Meléndez

Installation view: Bea Schlingelhoff, No River to Cross, Mapping, 2021. Courtesy the artist and Kunstverein München e.V.; photo: Constanza Meléndez

Installation view: Bea Schlingelhoff, No River to Cross, Mapping, 2021. Courtesy the artist and Kunstverein München e.V.; photo: Constanza Meléndez

Installation view: Bea Schlingelhoff, No River to Cross, Mapping, 2021. Courtesy the artist and Kunstverein München e.V.; photo: Constanza Meléndez

Installation view: Bea Schlingelhoff, No River to Cross, Mapping, 2021. Courtesy the artist and Kunstverein München e.V.; photo: Constanza Meléndez

Installation view: Bea Schlingelhoff, No River to Cross, Mapping, 2021. Courtesy the artist and Kunstverein München e.V.; photo: Constanza Meléndez

Installation view: Bea Schlingelhoff, No River to Cross, Mapping, 2021. Courtesy the artist and Kunstverein München e.V.; photo: Constanza Meléndez

Installation view: Bea Schlingelhoff, No River to Cross, Mapping, 2021. Courtesy the artist and Kunstverein München e.V.; photo: Constanza Meléndez

Installation view: Bea Schlingelhoff, No River to Cross, Mapping, 2021. Courtesy the artist and Kunstverein München e.V.; photo: Constanza Meléndez

Installation view: Bea Schlingelhoff, No River to Cross, Mapping, 2021. Courtesy the artist and Kunstverein München e.V.; photo: Constanza Meléndez

Installation view: Bea Schlingelhoff, No River to Cross, Mapping, 2021. Courtesy the artist and Kunstverein München e.V.; photo: Constanza Meléndez

Installation view: Bea Schlingelhoff, No River to Cross, Mapping, 2021. Courtesy the artist and Kunstverein München e.V.; photo: Constanza Meléndez

Installation view: Bea Schlingelhoff, No River to Cross, Mapping, 2021. Courtesy the artist and Kunstverein München e.V.; photo: Constanza Meléndez

Installation view: Bea Schlingelhoff, No River to Cross, Mapping, 2021. Courtesy the artist and Kunstverein München e.V.; photo: Constanza Meléndez

Installation view: Bea Schlingelhoff, No River to Cross, Mapping, 2021. Courtesy the artist and Kunstverein München e.V.; photo: Constanza Meléndez

Installationsansicht: Bea Schlingelhoff, No River to Cross, Mapping, 2021; No River to Cross, Präambel, angenommen von den Mitgliedern des Kunstverein München am 19.08.2021, 2021. Courtesy die Künstlerin und Kunstverein München e.V.; Foto: Constanza Meléndez

Installation view: Bea Schlingelhoff, No River to Cross, Preamble, accepted by the members of the Kunstverein München on 19.08.2021, 2021; No River to Cross, Mapping, 2021. Courtesy the artist and Kunstverein München e.V.; photo: Constanza Meléndez

Installation view: Bea Schlingelhoff, No River to Cross, Preamble, accepted by the members of the Kunstverein München on 19.08.2021, 2021. Courtesy the artist and Kunstverein München e.V.; photo: Constanza Meléndez

Installation view: Bea Schlingelhoff, Vier Künstlerinnen der „Entarteten Kunst“ Ausstellung in München, 2021. Courtesy the artist and Kunstverein München e.V.; photo: Constanza Meléndez