When we endlessly ruminate over distant times, we miss extraordinary things in the present moment. These extraordinary things are, in actual fact, all we have: the here and now.

Katherine May, Wintering: The Power of Rest and Retreat in Difficult Times (2020)

You cannot be immune to downfall, loss and dirt, Kathy knew, but sometimes an afternoon is separate, its own gold sphere.

Olivia Laing, Crudo (2018)

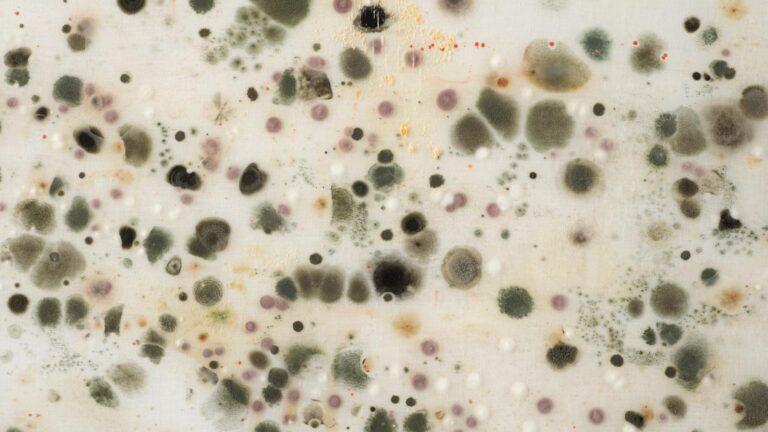

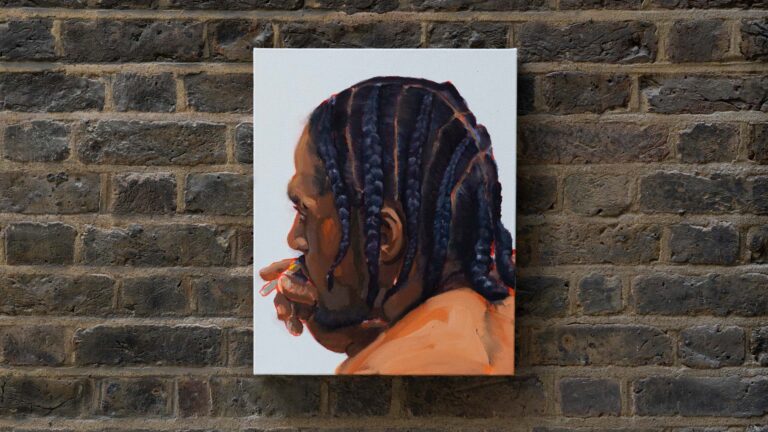

The paintings of Aya Higuchi (b. 1988, Tokyo, Japan) are moments of pause and poetry in canvas form; quietly intimate depictions of quotidian or natural encounters. They are simple pleasures: a glazed doughnut on a china plate, a morning walk drenched in misty sunlight, or even simply an ice cold glass of water. Amidst the glaring blue lights of screens and increasingly saturated images which compete for our attention daily, the quietness of Higuchi’s art is poignant. The visible brush strokes which sweep across her canvases give these images the impression of being viewed through the misted glass of memory, or perhaps a dream. Her work embodies the Danish principle of hygge, which has been called– appropriately- the ‘art of creating intimacy’, or Katherine May’s book Wintering, which is a celebration of life’s fallow (slower) moments.

The concept of ‘wintering’ seems appropriate, both for Higuchi’s subject matter and the time of year during which we view it. ‘In the mountain strong wind’ is a lyrical statement, evoking the thin clouds of cold blue skies, or the swaying movements of flowers in a breeze. It is a reminder that slowing down, resting, and embracing the restorative powers of the natural world is a radical act. As May articulates the adaptation of flora and fauna to winter as a lesson for humans through words, Higuchi does so through images. She suggests to us that to ground ourselves in the seasons– and consequently, to find comfort in everyday rituals and stillness, can be healing. After all, following winter comes the lightness of spring.

Higuchi’s paintings also, in their absence of figures and often singular subjects (one jelly, one spoon, one glass), suggest an alone-ness, yet one which is not of lack, but of contentment and comfortability. As painting itself is a meditative, solitary act, Higuchi’s scenes are the time put aside to connect with oneself: a cocotte cake and a cup of tea on a Sunday afternoon; the minutes spent arranging flowers before placing them on the mantelpiece. After all, as Olivia Laing writes in The Lonely City: Adventures in the Art of Being Alone (2016), “Loneliness, longing, does not mean one has failed, but simply that one is alive.”

–TEXT BY ELLA SLATER