A tear in the paper sky

The most striking feature of the world right now is that most of its inhabitants seem cut off from the future. Yet, life seems to hold little meaning unless it can project itself forward—ripen, progress, and take root. To live against a wall like that is to live a dog’s life.1

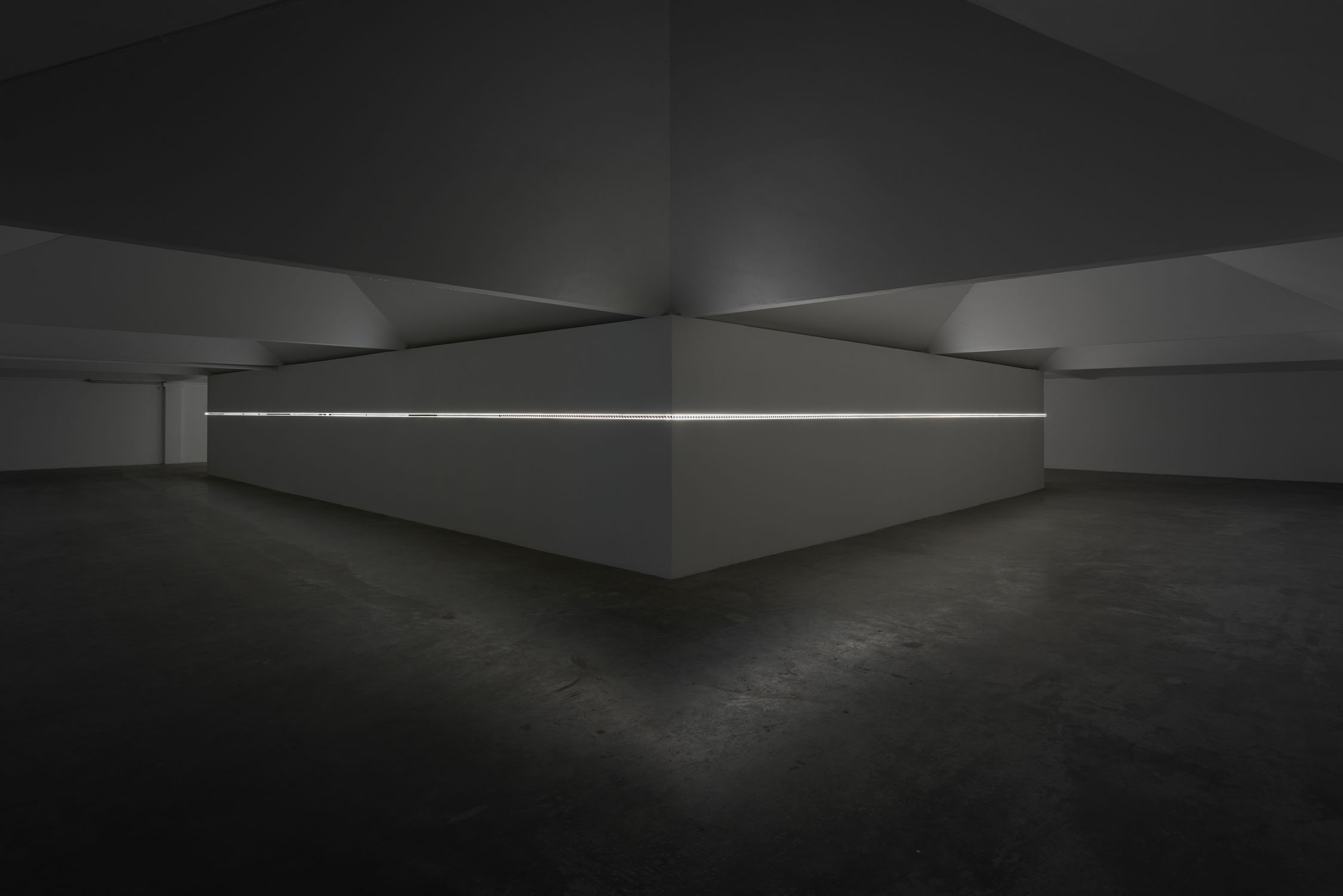

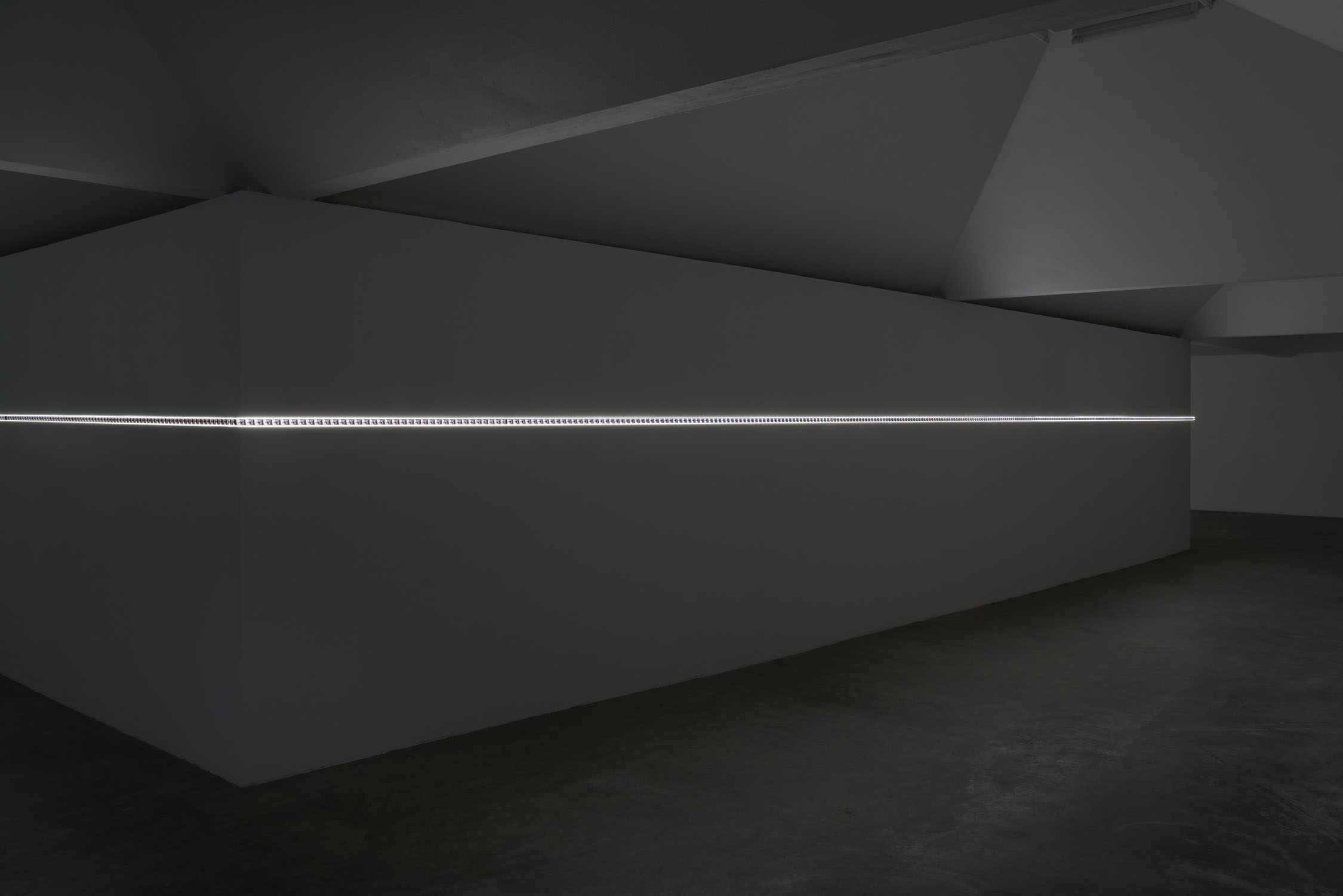

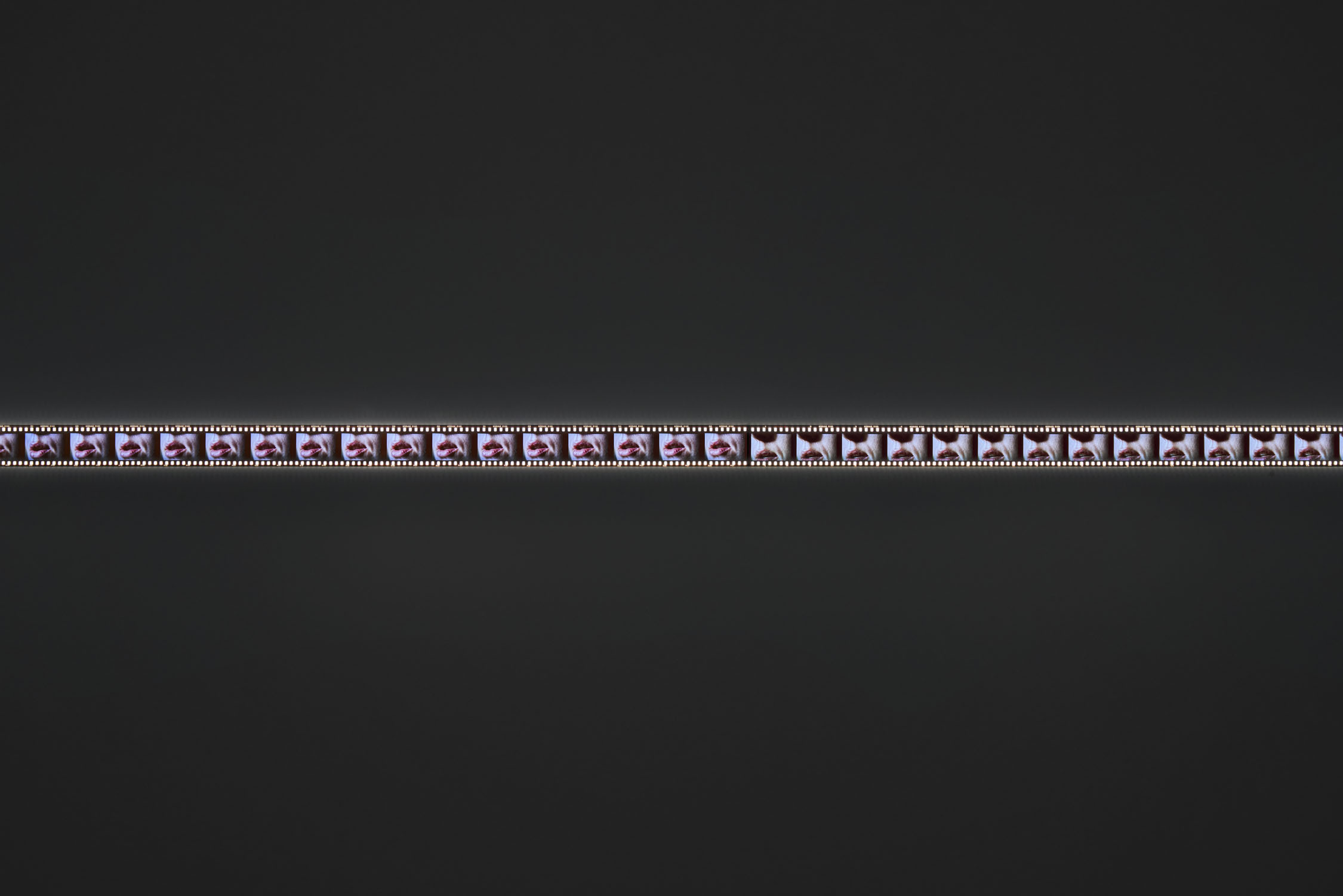

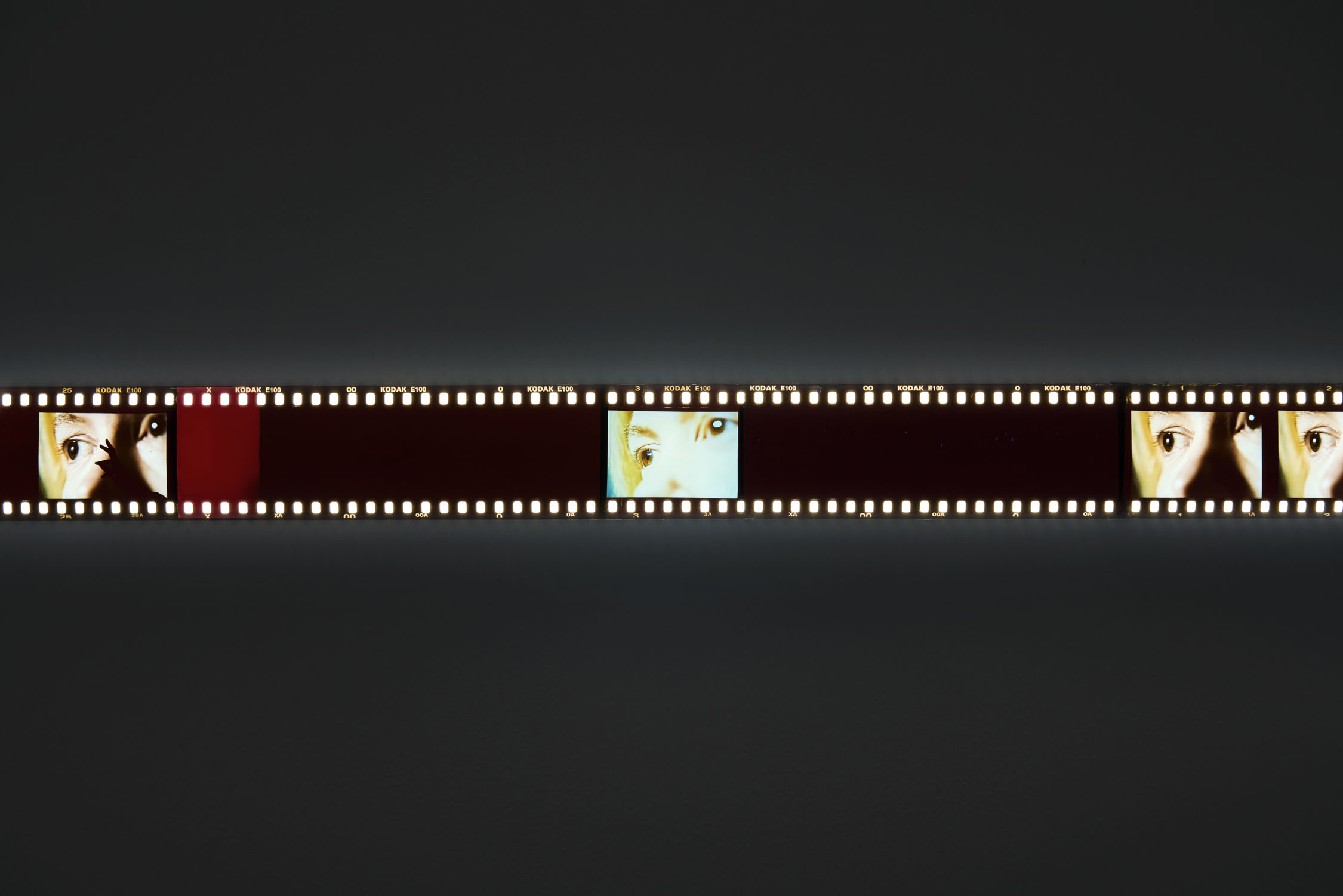

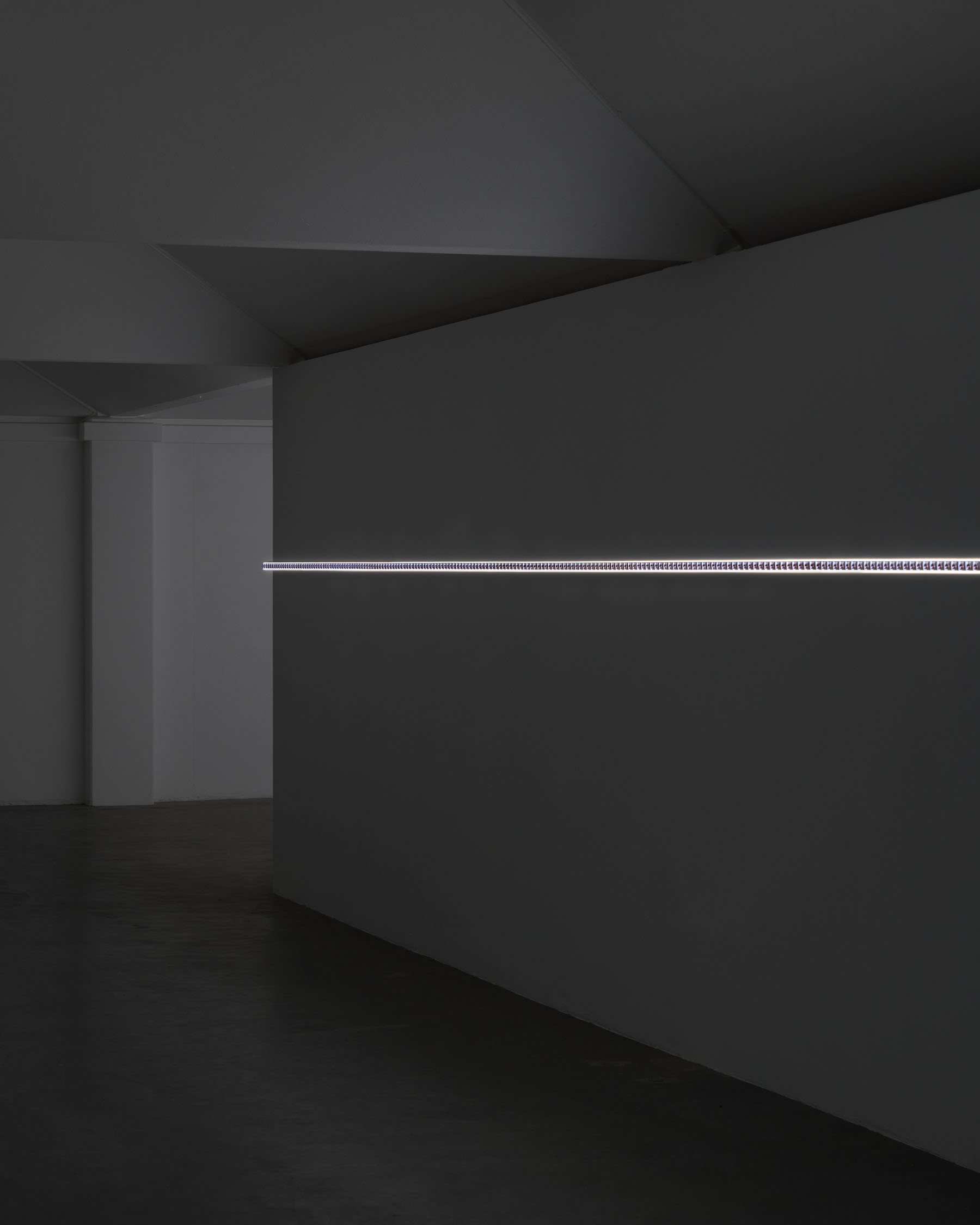

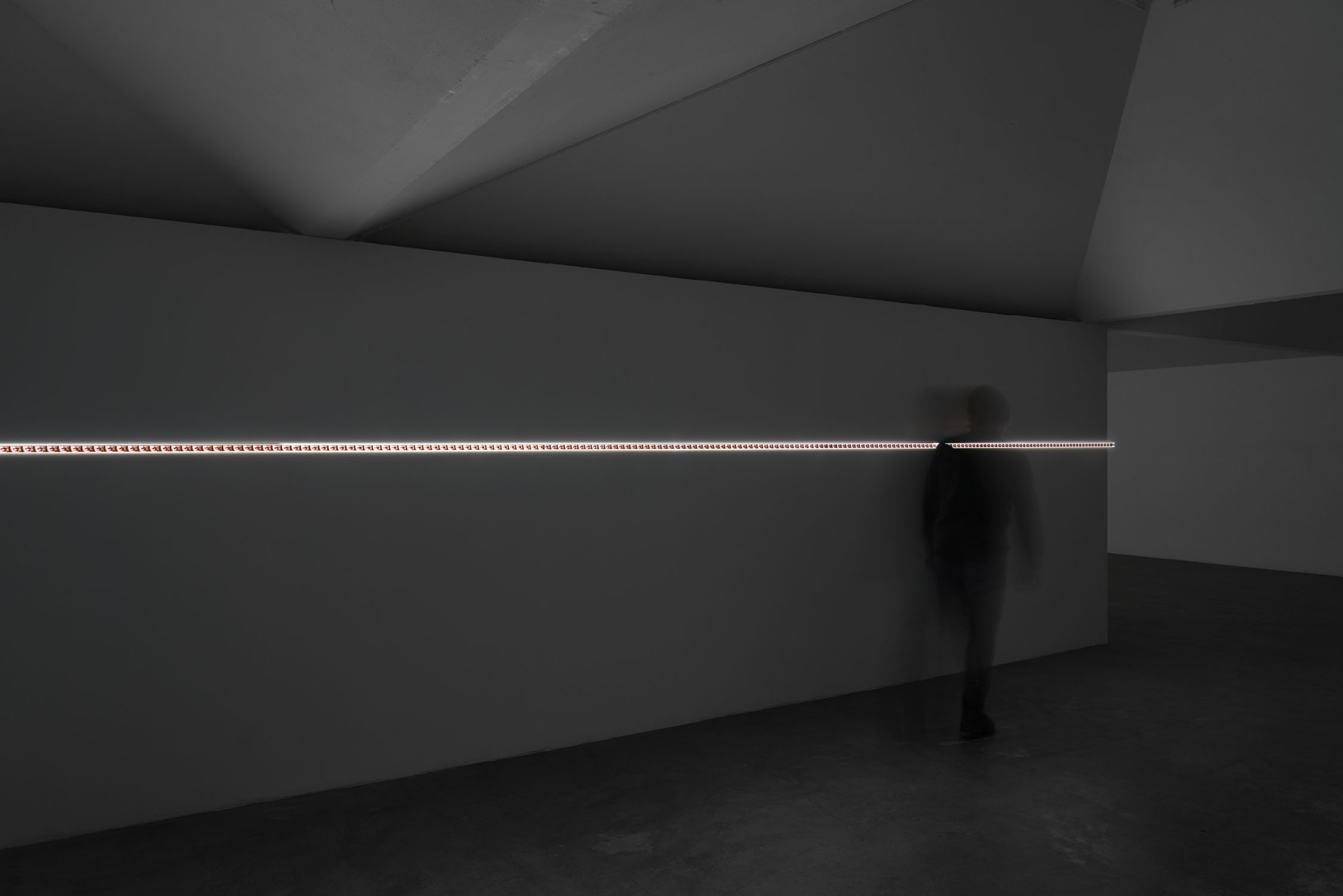

Angharad Williams seems to be channeling Albert Camus in her elusive Solo Performance, which stretches across the gallery as an unprocessed 35mm film roll, backlit and silent. In its naked celluloid state, the work presents a close-up of the artist herself, speaking something unsayable. Yet, because of the medium and the artist’s intent, the words remain out of reach. We cannot hear her. We weren’t there. What remains is a residue—a trace of a performance that exists as a visual enigma.

Something unspoken also pulls at the image Williams chose as her title, “The Bottom Dogs II”: dogs at the bottom of a well, pressed against curved walls, bodies crowded one above the other. The image carries the weight of limits, those boundaries that shape both animal and human lives, making existence simultaneously ordinary and impossible. That “II” in the title doesn’t point back to any first part. Perhaps it simply marks how things repeat, how they stall and stay the same. When a dead end becomes a picture of human helplessness, when indifference alone explains why things are as they are, even partial or no speech becomes a kind of testimony.

Installed as a luminous strip against the gallery wall, Solo Performance, Williams’ ‘unplayed’ film creates a boundary but not a physical barrier. Like a threshold of legibility, but the artist speaks. We see it: the movement, the shape of words captured in film stock. But the speech itself remains just out of reach. This isn’t absence—the words are there— but speech made deliberately inaccessible.

Angharad Williams always chooses paths that shift beneath her feet. Her work traces the space where the quiet violence of accepted hierarchies meets individual conscience—where personal choices turn psychedelic facing the weight of larger forces.2 Her exhibitions often start somewhere unlikely, almost improbable and disorienting. What seems at first like exaggeration, like pushing too far to extremes that seem unreal, ends up looking modest compared to what reality delivers, as if the world itself in the meantime had learned to speak in headlines.

The structure of Solo Performance follows documentary principles, though it claims no objectivity. It collects some fragments: bare sequences, no more than essential moments, each frame a fact in itself. Its geometric arrangement, almost diagrammatic in the way the frames line up and repeat, suggests there is intention but without insisting on it. The work resists passivity, it asks us to do more than watch and follow. As images shift from left to right, right to left, we find ourselves moving too, trying different distances, different angles. We can follow where it leads or find our own path through, letting these fragments settle into a pattern or mosaic we recognize—mutable, incomplete but true enough to hold close, and keep going

And yet, at some point, the effort becomes too much. The weight of looking, of trying to piece things together, starts to wear us down. What now? We walk the line of the wall, or crouch at its base, feeling our grip loosen. Clarity keeps receding, like a horizon that moves with us until exhaustion sets in. The floor starts to wobble. All kinds of memories surface—some may not even be our own— and sink like heat mirages on the edge of vision. Everything feels simultaneously overwhelming and empty, as if we’ve stared so long the light has gone out of things.

Subheading here

In this haze, something draws us down: a slow collapse of time and place. Maybe it’s the weight of summer heat, now gone, or traces of the artist wandering through the volcanic south of Italy last July. These ancient grounds linger and work on the mind, showing how close the sky can seem, while reminding us how far we have to fall. From these depths, a story surfaces like a fever dream: in the dusty files of Fascist police records, the disappearance of a young Sicilian physicist, Ettore Majorana, unfolds into something stranger than fiction.3

In March 1938, the Italian scientist boarded a ferry from Palermo to Naples, but he never arrived. Reclusive and solitary, he was described by many as one of those rare geniuses who appear only once, or perhaps twice, in a century. He moved between universities in Germany, Naples, and Rome, spending long periods in study and research. When he disappeared, he left no trace, not even a word. His extensive correspondence with his family offered no clues, just silence.

Some believe that Majorana discovered the power of atomic energy months before the atom was split and its potential revealed to the world. A plausible terror—or even a faint but inescapable sense of horror—must have taken hold of his conscience. From our vantage point now, it seems clearer and clearer that his decision to vanish into silence was not the act of a desperate neurotic but the deliberate refusal of a scientist who could not bear the weight of what he had seen.4

The media produced its theories: madness, suicide, political plots. But in Sicily, where silence often carries its own meaning, these explanations fell short. Majorana’s disappearance wasn’t a mystery waiting to be solved. Something in Sicilian culture, in its long familiarity with strategic, deliberate, silence, understood what others could not: sometimes, the absence of explanation is the explanation.

Faced with the monumental questions of science at the time, Majorana chose, ethically, the ultimate retreat. His disappearance cuts through history just as Williams’ deliberate muteness breaks through the expectations of performance. Both acts find their power not in what they explain, but in what they refuse to say.

Choosing silence is not always an escape. R.S. Thomas knew this well, moving through the Welsh hills with a particular stubbornness. As a priest and poet, he turned away from small comforts — refrigerators, television screens, gadgets — and dedicated himself to God and his writing. Not from a simple distaste of modern life, but because he saw how these distractions could dull the soul, and how attention might slip away into days filled with nothing but a soft, steady numbness.

Essentially, his silence had an edge. When he wrote about the Welsh landscape, empty of people, he wasn’t recording absence but charging it with energy and listening for something else. “I believe in revelation,” he wrote, “and therefore one cannot describe all one’s insights as entirely human.” 5 Something of this conviction echoes in Williams’ work, in how she lets meaning gather in the gaps between words, in the static between signals. Thomas wrote of “the true Wales of my imagination,” dreaming of a place kept immaculate ‘natural’, where people lived closer to the land’s own rhythms. Yet he was no romantic. His writing moved between the spiritual and something more conceptual, what he called the “adult geometry of the mind“—a way of measuring the hard edges of existence while acknowledging how modernity pressed against older ways of being, including having a relationship with god.6

Thomas’s silence grew from this clarity. His reputation for awkwardness, his distance from others, his quiet nature—these weren’t merely personality traits but became a kind of stance of performance. For a public figure, for writers, for artists, silence has its own presence. It rarely goes unnoticed, it takes up space, it carries weight. Thomas inhabited this space deliberately, though perhaps not always by choice. A priest who found the sacred in withdrawal, in the gap between what could be said and what had to remain unspoken. What, then, am I really shielding myself from?, he wrote.

The tear, the mask, the void

And yet, there’s a kind of absurdity in this pursuit of autonomy, something almost ancient in its simplicity. Like following a path without knowing where it leads, or turning away when everyone else leans in. Thomas’s poetry, Majorana’s vanishing, and Angharad Williams’s solo performance each trace this quiet line of retreat. Not as grand gestures or statements, but as small refusals that somehow persist. Perhaps what matters isn’t the silence itself, but the space it takes and opens, a pause in the rhythm of things.

The existential doubts of others often feel like distant echoes, harder to connect with or grasp than our own. We try to reach across this distance, to understand lives that aren’t ours, but something always slips away. Words pile up, explanations grow thin. Perhaps this is why we fall into silence, letting our thoughts curl back on themselves like thick clouds.

Look at any face you know well: the familiar smile, the cadence of a voice. You’d think you could map every detail, yet something stays hidden. Not dramatically concealed, just… elsewhere. When we try to imagine this other world, we end up painting it with our own colors, filling it with stuff from our own memories. This is what catches in Williams’ “performance”, or at least the document and archive we get to see. Her face speaks, but the image doesn’t. We stand there, watching, and for a moment the usual distance between seeing and understanding shifts slightly. Not because anything is revealed, but because the opacity itself becomes familiar—like recognizing your own reflection in a darkened window. The sequence isn’t trying to decode anything. It’s more like an invitation to sit with this strangeness, to let it be what it is. Sometimes understanding comes not from clarity, but from the quiet pleasure of getting lost in translation.

Wales exerts a genetic pull here. Something of Wales lingers in these frames, not as background or biography, but as a way of being. It’s there in how a language shapes the mouth that speaks it. Williams carries this landscape within, not as nostalgia or identity politics, but as inherited gesture, a tilt of the head, a way of holding silence, something that can only come from a specific place. Her face on film becomes a kind of map—not of places or meanings, but of small shifts and changes. We watch her speak and something familiar starts to waver, again like heat rising from summer roads. Is she performing, or is this what happens when performance falls away? The question brings to mind another Sicilian who understood these nuances, the playwright Luigi Pirandello.

In the 1930s, when silence abunded in movies too, Pirandello wrote of faces that couldn’t quite hold it together, of selves that split and doubled. His characters kept slipping out of their assigned roles, letting doubt seep in through the cracks. It wasn’t just theater anymore—something in the world itself had started to come loose. There’s a moment in his play Six Characters in Search of an Author when a character notices the decor and the ceiling of the theater tears open. It’s a small thing at first, hardly worth noticing. But through this tear, the ordinary world starts to unravel. Not dramatically, but in the quiet way that certainties sometimes fade, leaving only questions ahead and behind.7 It also changed European theatre and thought forever.

Williams works in this same territory, though she took a different path. Each frame of her film holds something we won’t possibly touch, the ceiling is elsewhere. Clues then, the gaps between frames become as important as the images themselves—little pauses where meaning creeps in, pools and settles. Like Pirandello’s tear in the paper ceiling, these intervals suggest that some truths only emerge in the spaces between what we try to say and the things we care about. Think again of the dogs beneath the pile, at the bottom of the well. Their howl isn’t heard but felt, their despair is imagined—a vibration that travels through bone and stone, that might just be strong enough to make the sky tear apart, fine as paper, clear as glass.

Notes:

1 Albert Camus, Neither Victims Nor Executioners (1946) by Albert Camus opens with: “The 17th century was the century of mathematics, the 18th that of the physical sciences, and the 19th that of biology. Our 20th century is the century of fear. I will be told that fear is not a science. But science must be somewhat involved since its latest theoretical advances have brought it to the point of negating itself while its perfected technology threatens the globe itself with destruction. Moreover, although fear itself cannot be considered a science, it is certainly a technique. The most striking feature of the world we live in is that most of its inhabitants—with the exception of pietists of various kinds—are cut off from the future. Life has no validity unless it can project itself toward the future. Living against a wall is a dog’s life. True, and the men of my generation, those who are going into the factories and the colleges, have lived and are living more and more like dogs.”

2 See: Joe Public (2022). In this black-and-white film, Williams portrays a doppelgänger traveling to rural Wales, performing mundane yet symbolically charged acts like visiting a car boot sale, eating a packed lunch, and shopping for a sho

3 Leonardo Sciascia’s 1975 book The Disappearance of Majorana was the first to suggest that the physicist choose to vanish for ethical reasons. What seemed at the time a controversial interpretation has gradually become the most widely accepted explanation of Majorana’s disappearance.

4Albert Camus, in The Myth of Sisyphus (1942), writes: “Il n’y a qu’un problème philosophique vraiment sérieux : c’est le suicide. Juger que la vie vaut ou ne vaut pas la peine d’être vécue, c’est répondre à la question fondamentale de la philosophie” (“There is but one truly serious philosophical problem, and that is suicide. Deciding whether or not life is worth living is to answer the fundamental question of philosophy”). The absurdity of life for Camus lies in the tension between humanity’s search for meaning and how silent the universe remains about it.

5 R.S. Thomas (1913–2000) was a Welsh poet and Anglican priest. His work explores themes of faith, silence, modernity, and the alienation of rural life. Known for his austerity and precision, Thomas was deeply critical of modern life. His poetry frequently returned to the rugged Welsh landscape, which he viewed not as a romantic idyll but as a charged space for existential reflection. His belief in the ineffable led him to assert that some truths must remain unspoken. In one of his later essays, he wrote: “It is to God that the mystery belongs, and woe to man when he interferes with that mystery.”

6The phrase “adult geometry of the mind” originates from R. S. Thomas’s poem “Emerging,” found in his collection Laboratories of the Spirit (1975). In the poem, Thomas explores the evolution of human consciousness and spirituality, suggesting a maturation from the instinctual “”adolescence of nature”” to a more structured, abstract understanding of existence—what he terms the “”adult geometry of the mind.”” This shift signifies not only a deeper recognition of divine presence in the world (“”God of form and number””) but also an awareness of humanity’s dual role in solving and expanding life’s questions. Circular though this journey may be, Thomas insists it is not regressive, leading instead toward a transcendent “”laboratory of the spirit,”” where intellect and faith converge.

7A quirky parallel may be found in “Five Characters in Search of an Exit,” an episode of The Twilight Zone (Season 3, Episode 14, 1961). Directly inspired by Luigi Pirandello’s Six Characters in Search of an Author, the episode follows five highly specific characters—a clown, a ballerina, a hobo, a bagpiper, and an army major—trapped in an abstract, featureless cylindrical room. As they try to make sense of the reasons behind their confinement, they start to question the reality of their existence. The twist ending flips their world upside down, reframing what they, and the audience, thought they knew.

Biography:

Angharad Williams is an artist, writer and performer from Ynys Môn, Wales. Selected solo exhibitions include Berlin Straße, Schiefe Zähne, Berlin, Germany (2024); New Technology, Fanta, Milan (2023); Eraser, Kunstverein Düsseldorf, Germany (2022); Picture the Others, MOSTYN, Llandudno, Wales (2022) and High Horse, Kevin Space, Vienna, Austria (2021). Angharad has participated in numerous group exhibitions at prestigious institutions and galleries such as museo Madre,

Naples (2024); The Wig, Berlin (2023); MadeIn Gallery, Shanghai (2023); Kunstverein Munich, Munich (2020). Performances have taken place at Kunsthalle Zurich (2022) and KW, Berlin (2020). Angharad’s first book Eraser was published by After8 Books, Paris in 2023. Forthcoming projects include the release of a limited 12” vinyl with Concentric Group, London & the Bauhaus Foundation, Dessau in 2025. Angharad is a guest teacher at the Masters Fine Art at Zürcher Hochschule der Künste, Zurich.