Artist: Amelie von Wulffen

Exhibition title: I Think We Did A Great Job

Venue: Galerie Barbara Weiss, Berlin, Germany

Date: March 10 – April 13, 2024

Photography: all images copyright and courtesy of the artist and Galerie Barbara Weiss, Berlin

Under the Poodle’s Skin

Over the last two or three years I’ve become increasingly aware of things that are actual and real, things that I see every day around me. These are all terms that you could easily put in inverted commas, but right now that’s the very last thing I’d want to do.

Some of the reasons for focusing more sharply on my immediate surroundings, and perhaps being a little more grateful for them, are obvious. I’d rather not go into them in detail, but so many political and environmental developments are so unsettling that I cling to the fact that things are still there and in their place day after day.

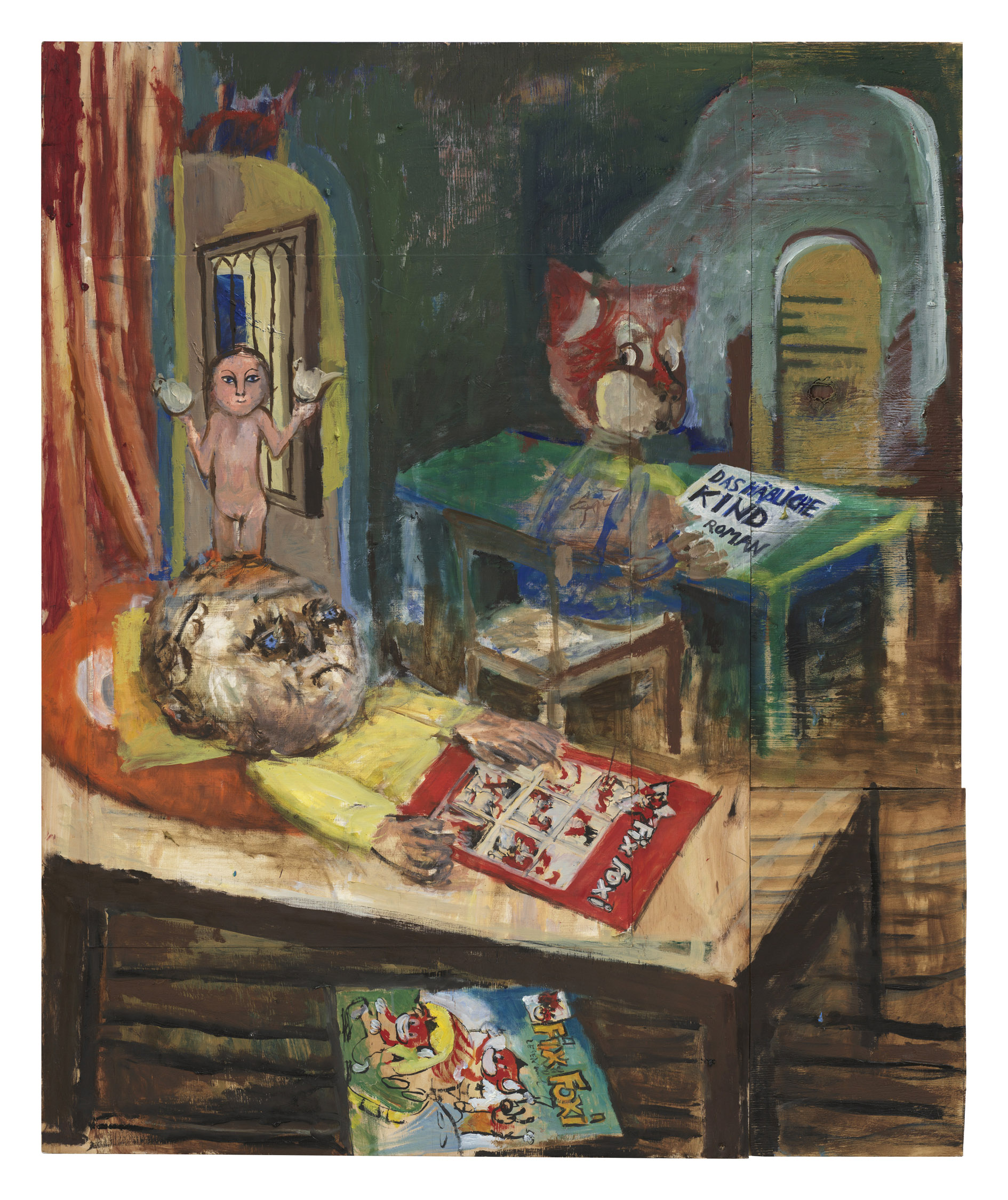

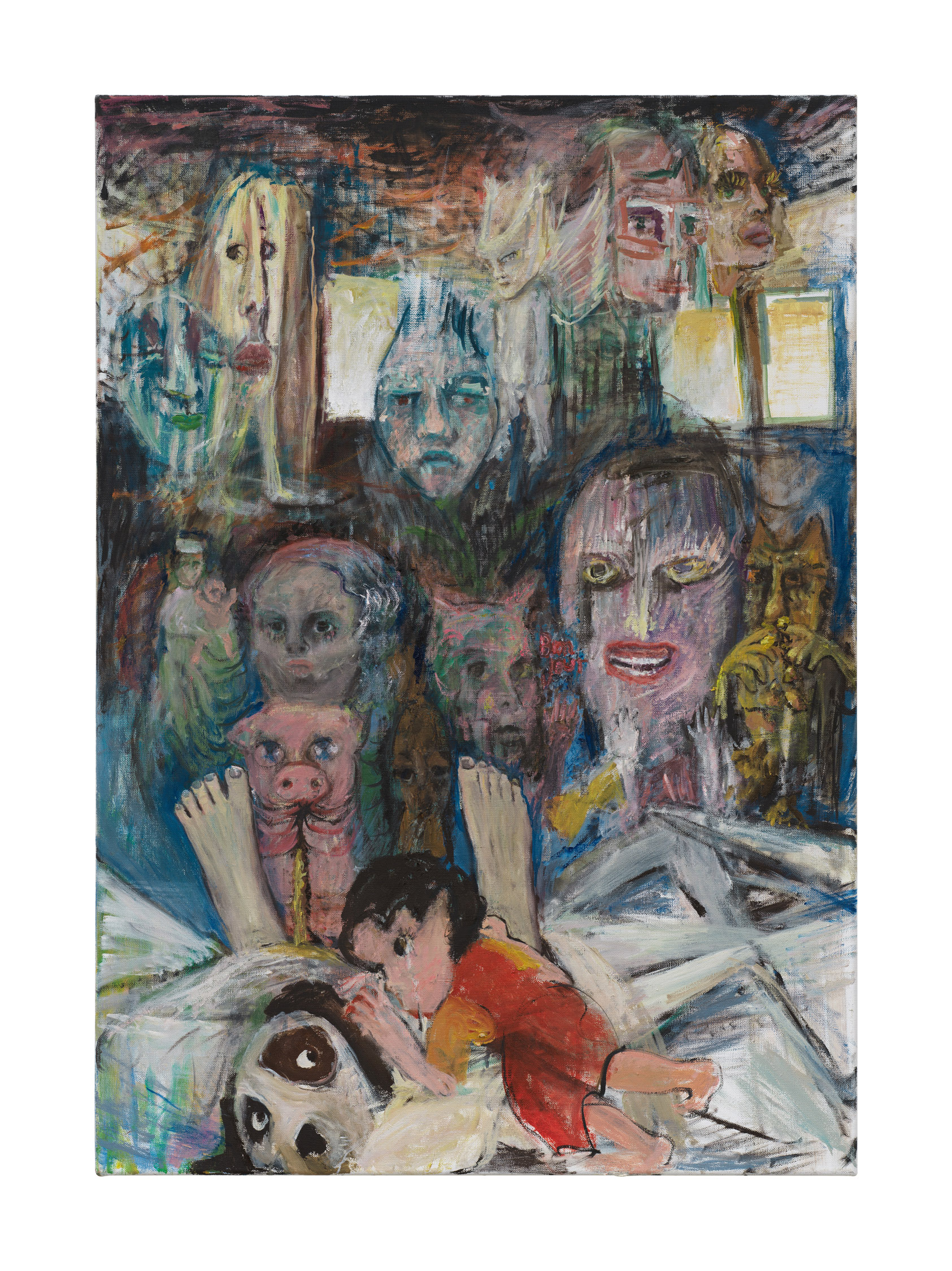

On top of all of this, my parents died within a few months of each other. Both had been seriously ill, needed a lot of care and support, and once again this brought out our highly complicated, dysfunctional family dynamic. Just when I foolishly thought things couldn’t get any worse, we happened to discover a secret that was so unbelievable, so hard to digest, that I still feel sick when I think about it and the pain it was still able to cause. Despite several courses of psychoanalysis, and endless time spent researching, remembering and reflecting, I hadn’t even begun to understand what had been wrong with my family. The heart of the matter – the “poodle’s core”, as Faust put it –had been hidden for over fifty years, and nothing had actually been as it appeared. In retrospect, I can understand why my paintings sought so often to dismantle apparent reality and superimpose other realities upon it, some arrived at by a process of association, others drawn rather from inner depths. I was trying to insist that “reality” is not something so easy to grasp; it is littered with things that, while being part of it, are nevertheless disavowed or repressed – and in any case, everyone has their own reality.

I used to assume that almost everything we had disavowed and repressed had to do with the Nazi period – but then I was proven otherwise. At least, things are not always so clear. But perhaps some people have learned to disavow and cover things up so well that they are able to masterfully practice this skill in almost every area of life.

After my parents died, I stopped travelling regularly to Bavaria, and I was looking for something that would bring some joy into my everyday life. So I bought a little poodle, and I have been taking him for daily walks through my neighborhood in Berlin, the Weissenseer Spitze, while imagining as exactly and precisely as I could what would happen if nuclear bombs were to fall on Berlin.

But everything is still there, as real and as peaceful as ever.

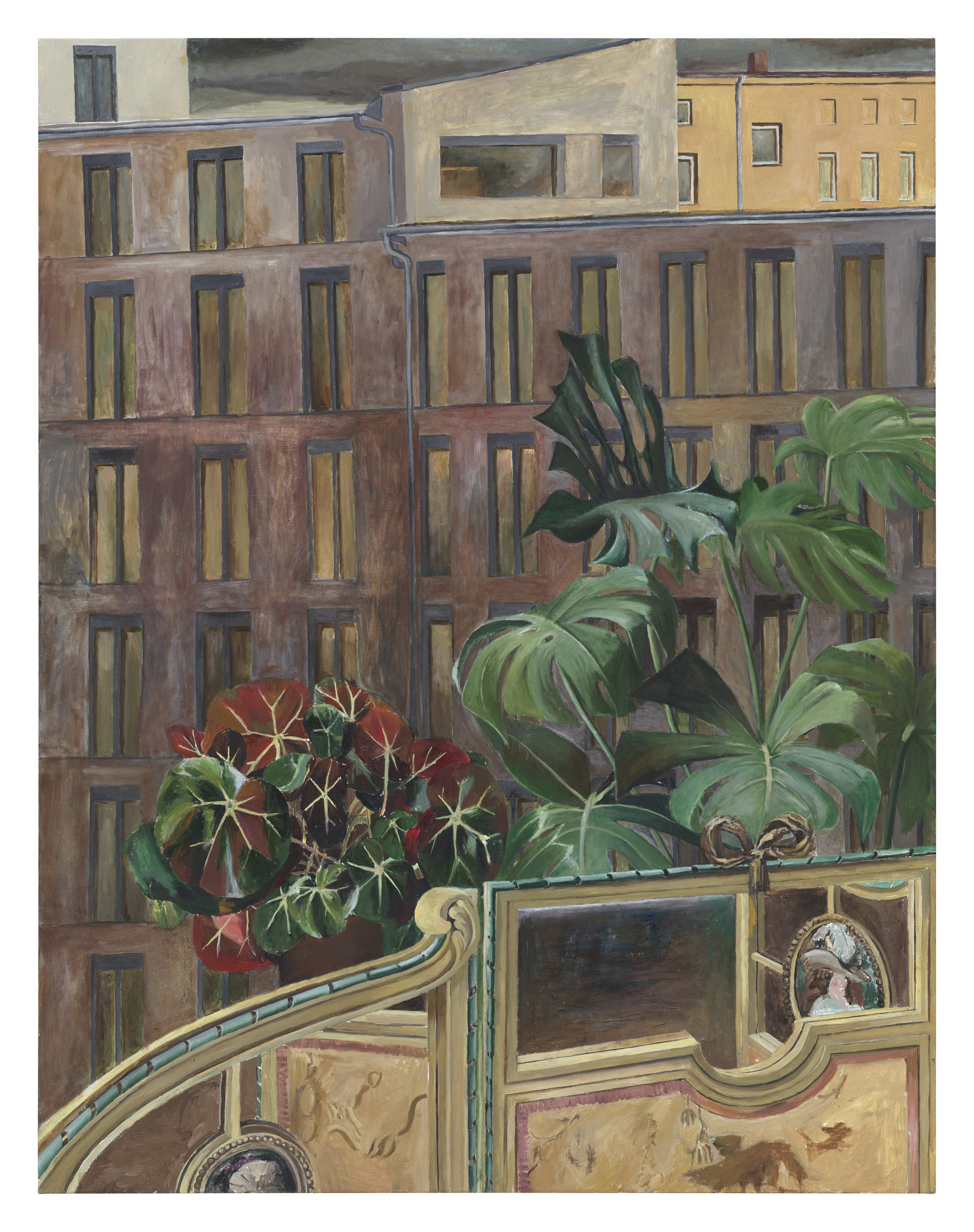

I want to document it in paintings, and I’ve been asking myself whether the current situation, the unease that many people are feeling at the moment, is similar to what gave rise to the Neue Sachlichkeit of the twenties and thirties. Did the urgent need to paint pictures of houseplants, a glass of water, the view from the window or one’s own face emerge from a general sense of being under threat?

You might call it Panic Realism, if you’re fond of catchphrases.

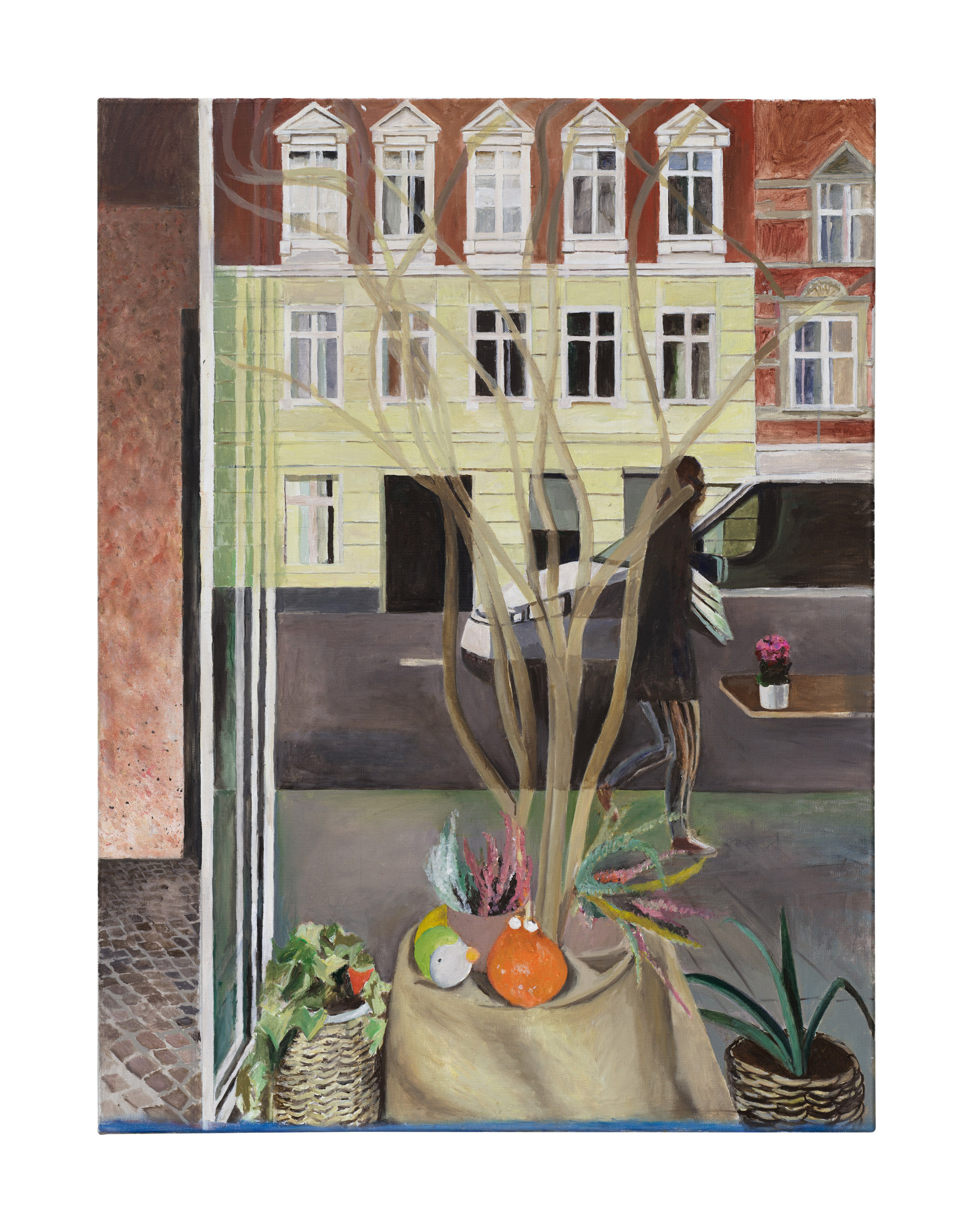

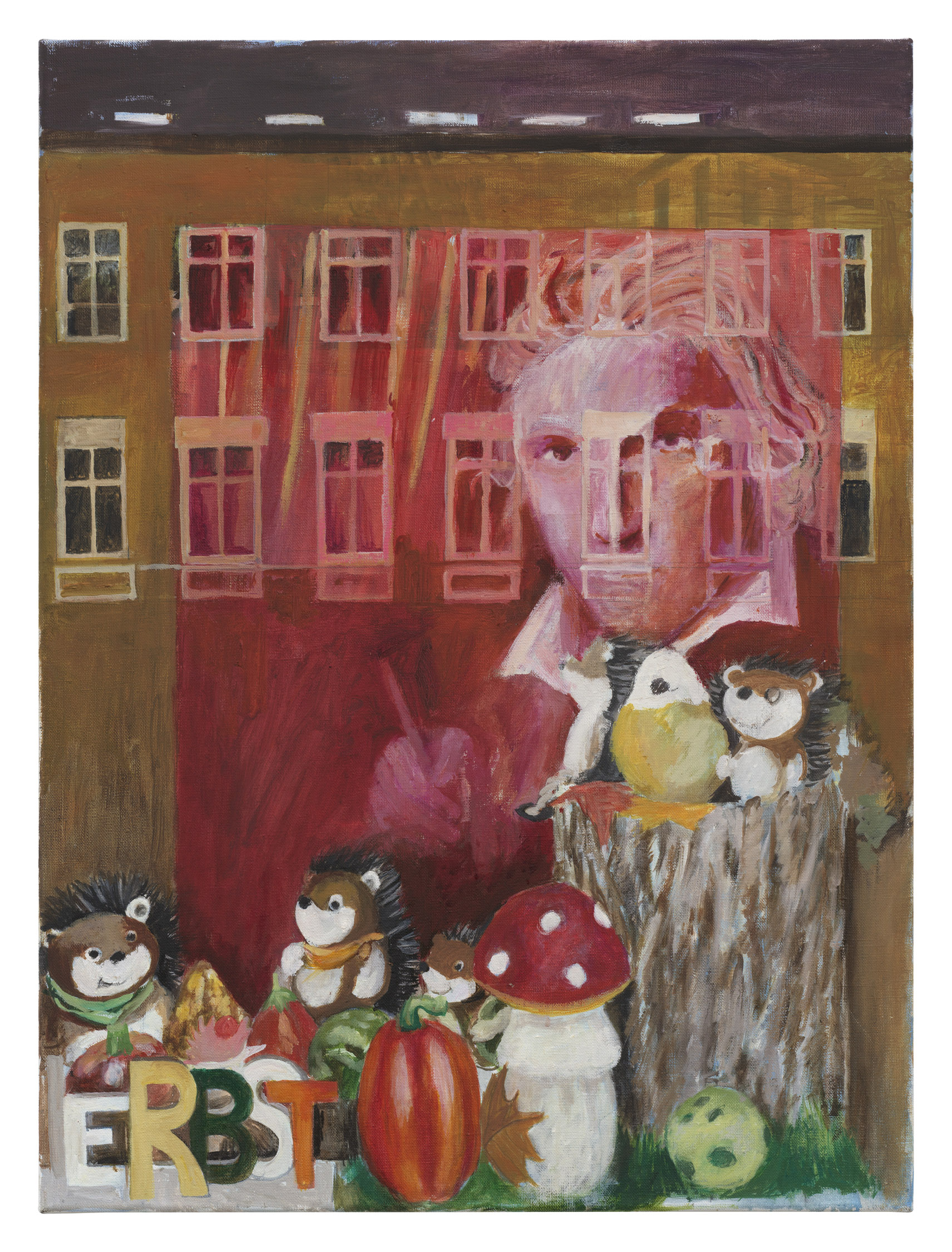

Weissensee – a district near Prenzlauer Berg, in the former East Berlin – is only now being gentrified. Land and house prices have exploded, but most of it still looks run-down and impoverished. The decorations you can see in people’s front gardens and in apartment and shop windows are depressing, but also touching; depending on my mood, they can cheer me up or they can get me down. What’s for certain, however, is that they are all soon going to disappear.

The objects, figures and materials you see in them are always the same. All the people decorating shop windows shop at KiK, Woolworth and Blume 2000. All recreational gardeners shop at Hellweg, Bauhaus and Obi.

There are hedgehogs, snowmen, snowflakes, gnomes, smiling fruit octopuses, bunny rabbits or Buddhas seated on plastic grass, all made of either plastic or stoneware.

You can also find all kinds of objects made of natural materials in the shop windows: raffia screens, dried pumpkins, pine cones, artificial flowers, spheres made of bent twigs, seed pods, and so on. The materials often allude to the changing seasons. And the shop windows almost always have plastic heads or cute little Mr. Potato Head-style figurines, identificatory figures without bodies.

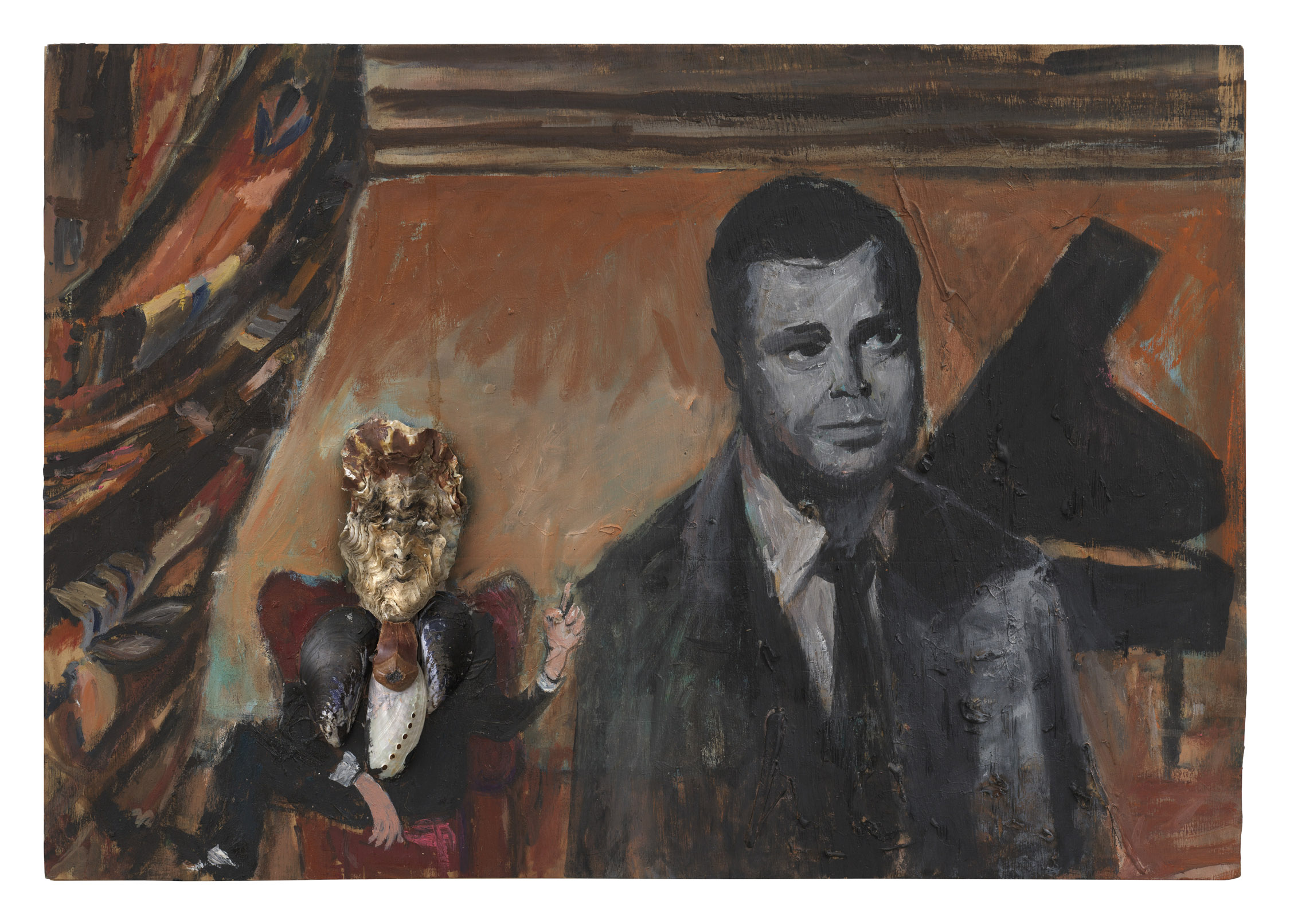

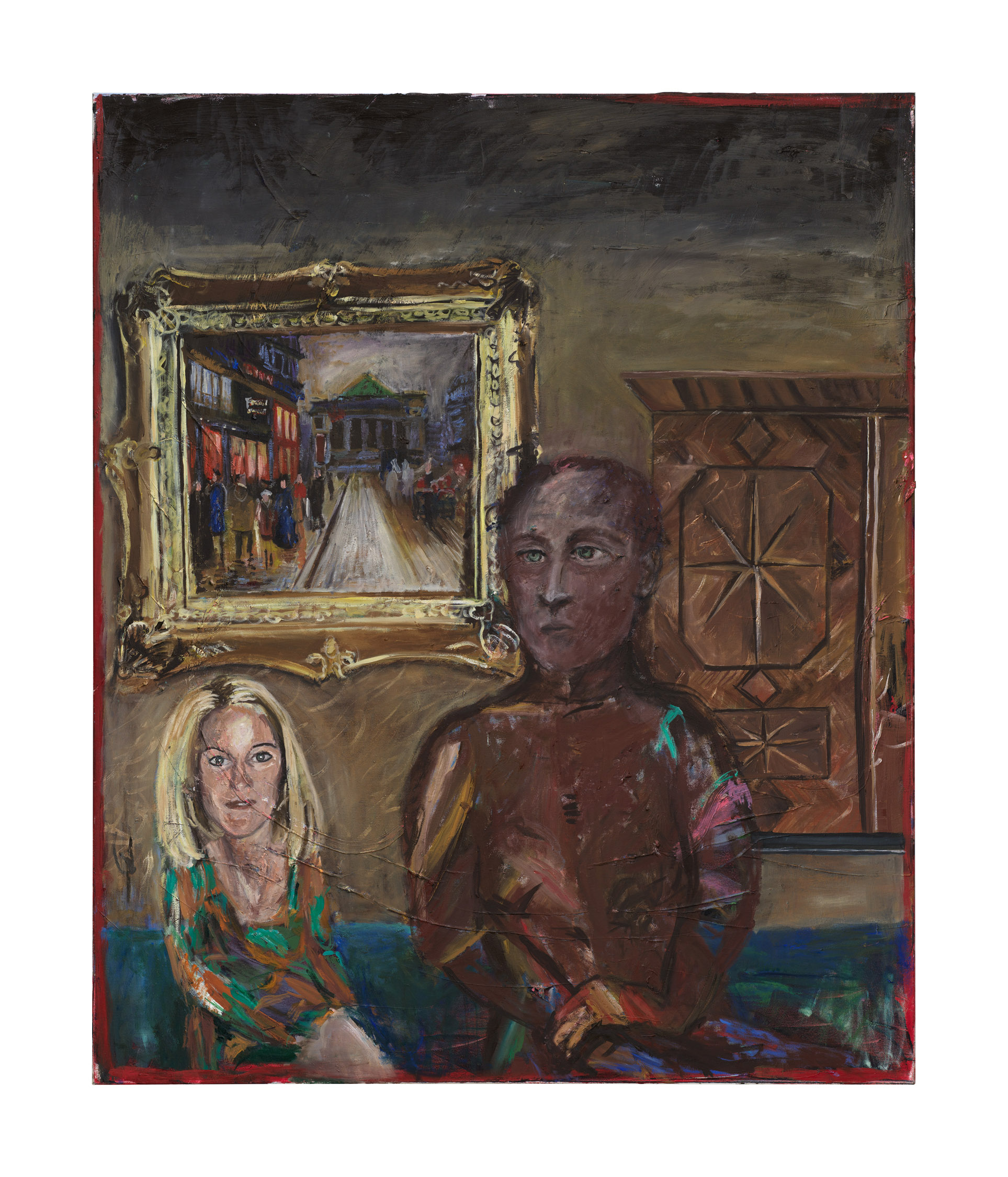

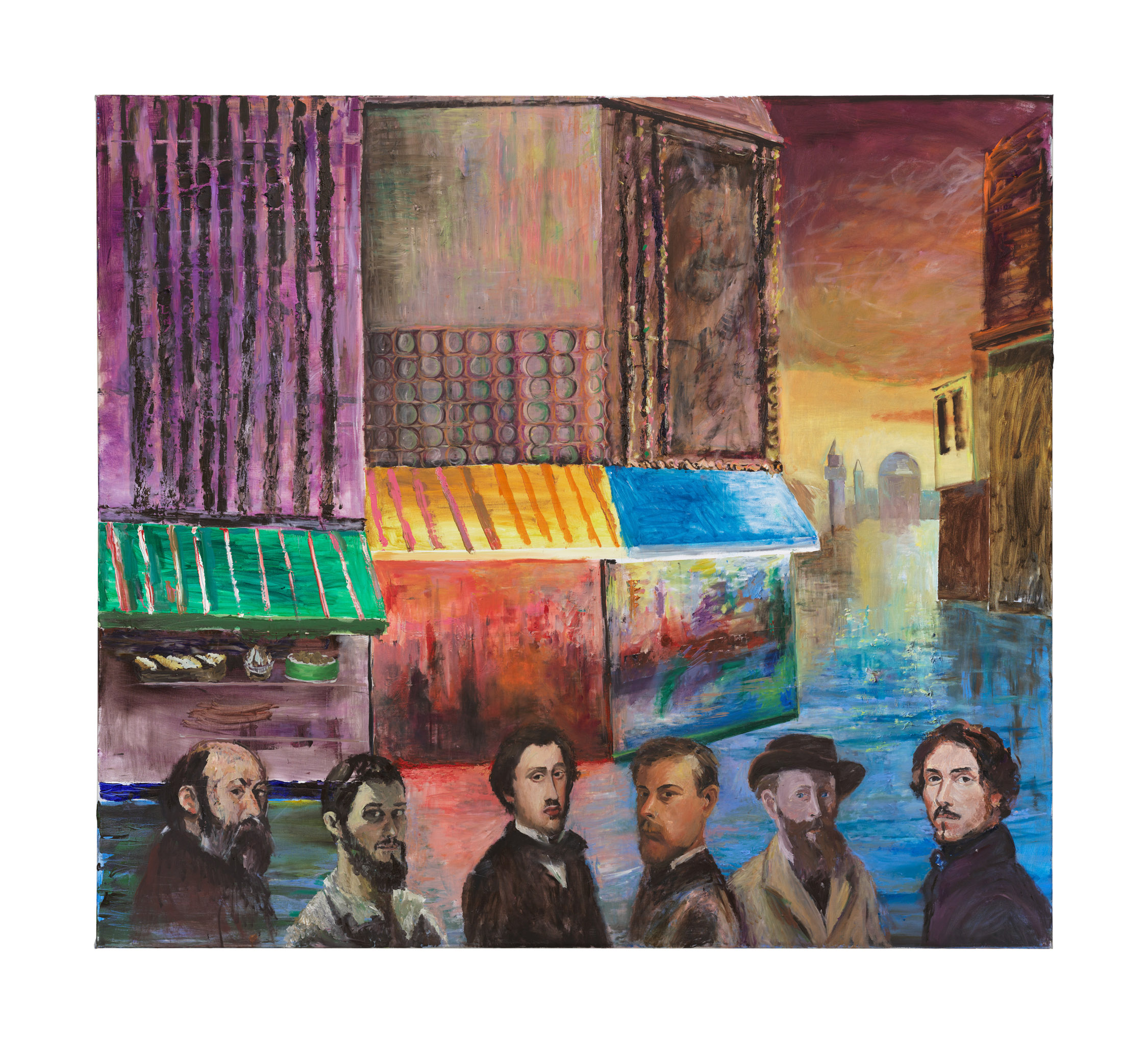

The handmade, often clumsy-looking arrangements and compositions are approachable and in some ways almost appealing, despite the abysmal nature that these little idylls also radiate. There are parallels here with Parisian tourist paintings, which continue the Impressionist style in such a strange way, and also the painted seascapes found in Italian or Croatian coastal towns have parallels to this; they all evoke something similar for me. These paintings operate along very well-trodden paths, with a few varied artistic tricks – applying paint with a palette knife, doing a bit of stippling, strong contrasts of light and shadow, lots of highlights and reflections after a rain shower, artificial light coming up against daylight, etc. – and voilà, you’ve got a piece of that peculiar thing, “reality”. The quotation marks are truly appropriate here. Just like the snowmen, hedgehogs, and rabbits in their window arrangements, the paintings emerge from a kind of creative industry, where highly prefabricated meets the handmade.

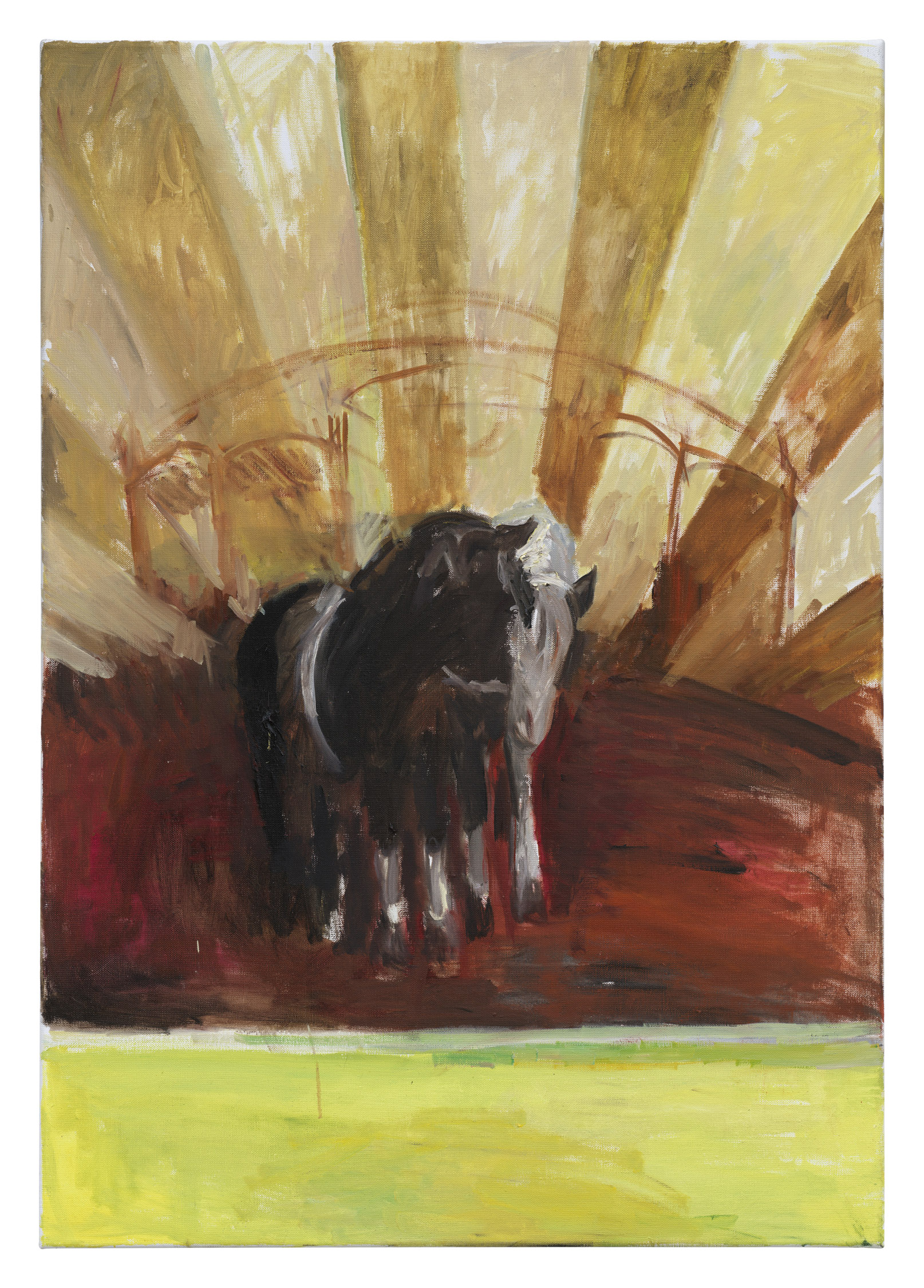

On the face of it, the Parisian scenes produced by this standardized method of painting relate to actual places in Paris (such as the Eiffel Tower or the Paris Opera); in fact, however, they are fictional in the highest degree. Life in them plays out in another material, almost in another dimension. It’s as if you were wading through a multicoloured jelly of paint, in which people and horses, also made of jelly, are hurrying here and there. Everyone is a three-dimensional paint mark, sometimes applied with a brush, sometimes with a palette knife, and everyone has the same shape, the same “fur collars” and “hats”; the only thing that distinguishes them is the colour of their clothing.

I knew these paintings in my childhood and teenage years; I no longer remember how I came across them, but I half-consciously studied them and my fantasies of becoming an artist and living in cool metropolises, far from my family, became bound up with them. The paintings always have a strongly atmospheric light and often show Bohemian bars and clubs; they still remind me of the longing I had to travel and of how much I was looking forward to life.

Berlin painting (e.g. Menzel) and in fact the whole of German painting (with the exception of Caspar David Friedrich, Runge, Altdorfer and Dürer in his watercolours) didn’t care very much about light. And my Berlin paintings don’t have much light in them either. That doesn’t mean they are dark; light here is functional and remains external to the things it illuminates.

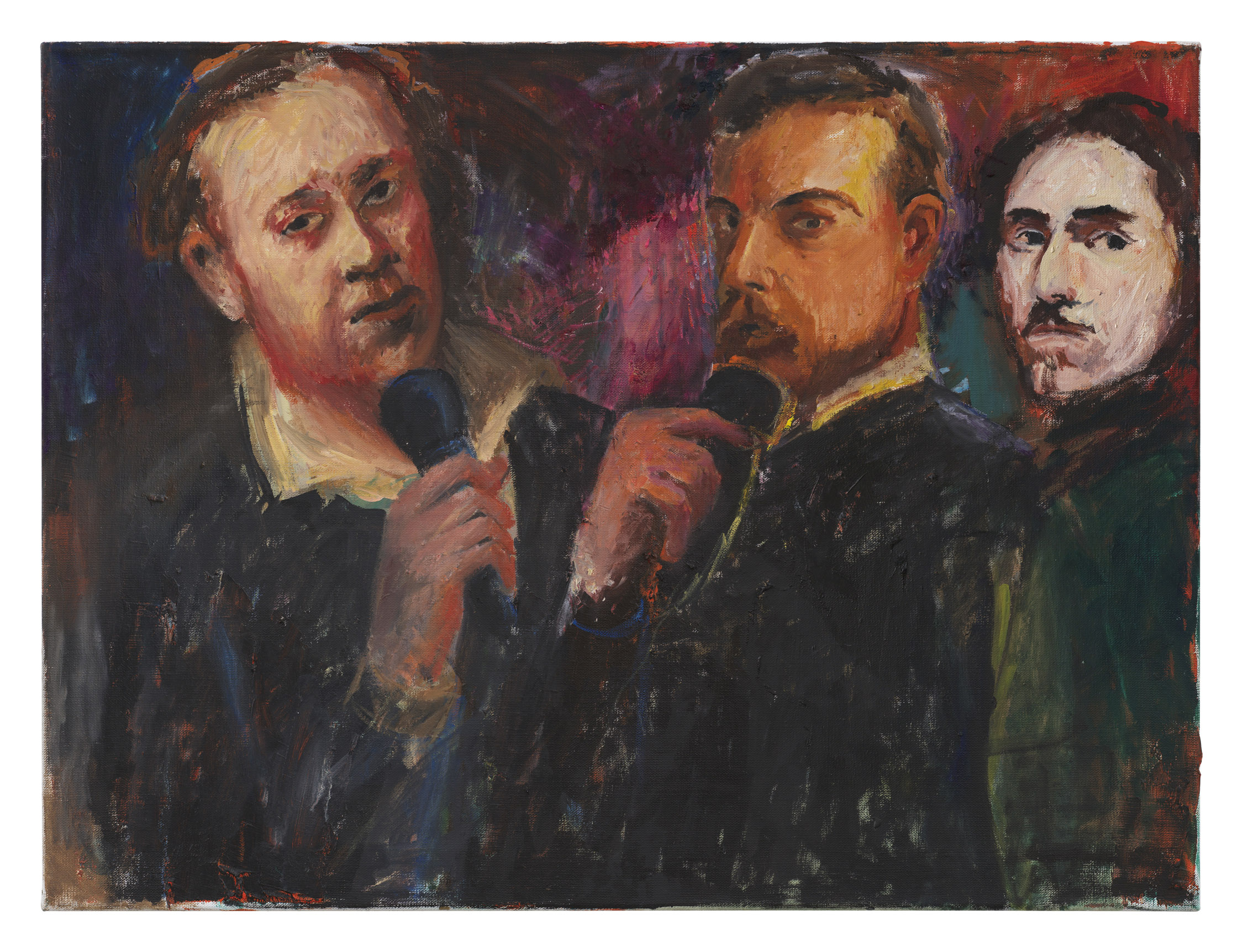

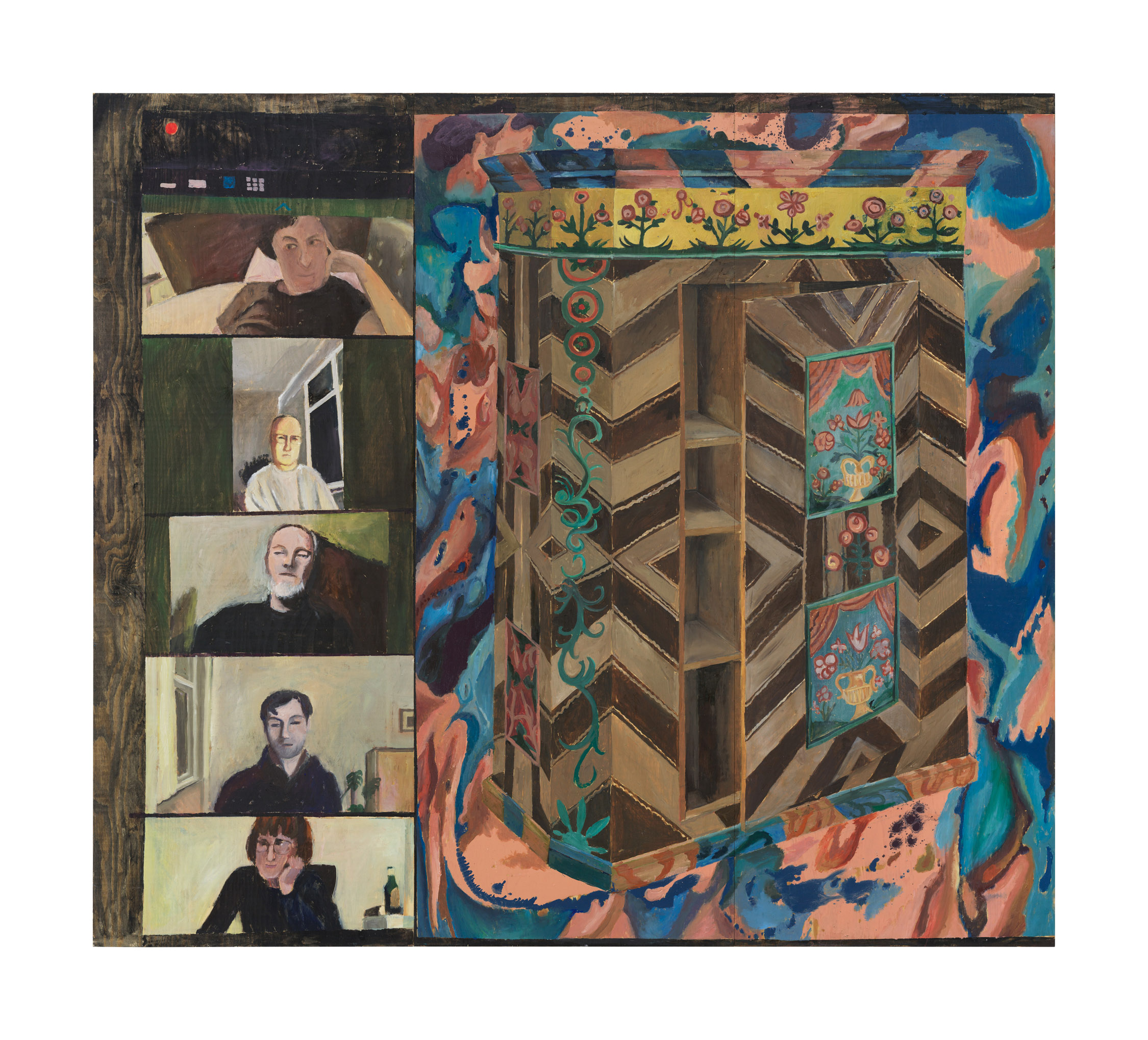

In Seminar/ Bauernschrank, the people attending a seminar are sitting in their bare, scantily furnished rooms, also under the Berlin non-light – strictly speaking, under an inhospitable, artificial light. It has to be said that, as far as light and colour go, Zoom is still relatively human – at least it shows a skin colour that looks soft and warm, unlike the wrinkled porcine faces that you get on Facetime.

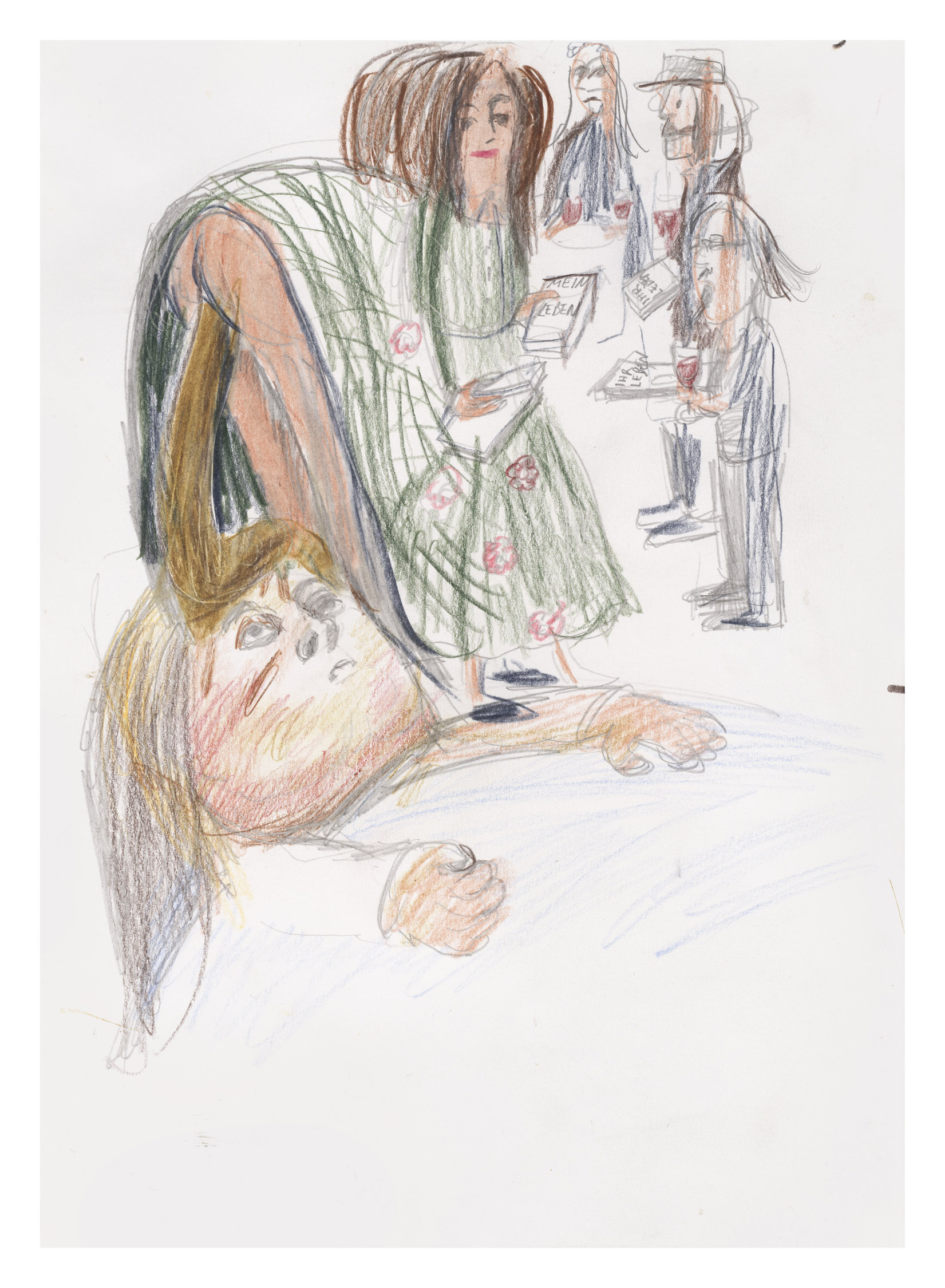

The art enthusiasts pictured in the painting are like the hedgehogs or the neon-colored Styrofoam heads in the shop windows, lined up and disembodied. They have gathered to think and talk about a rustic wardrobe.

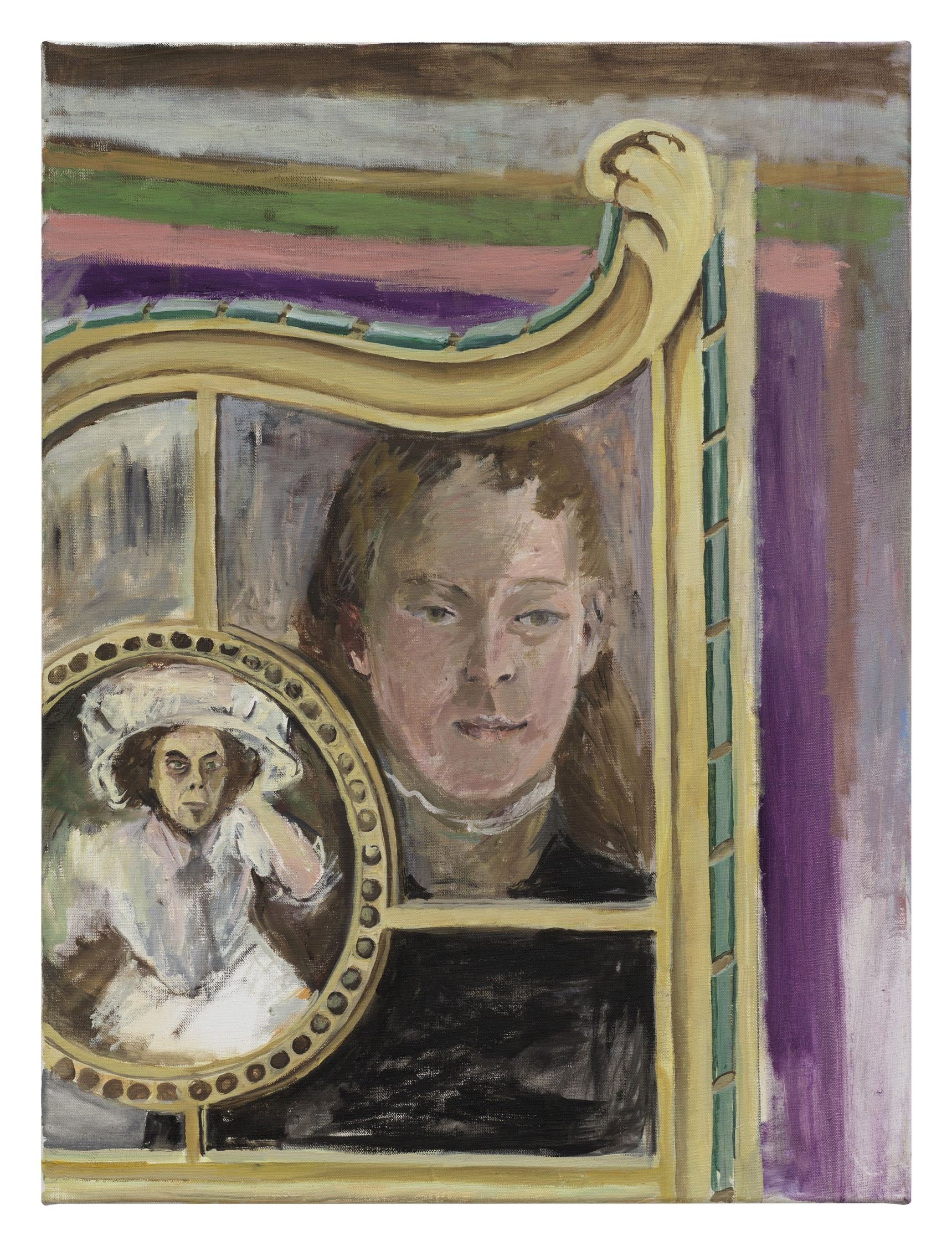

The wardrobe is eighteenth or nineteenth century, and is an example of Alpine folk art. It can be seen as representative of Germany’s dark Nazi past, as it has been described in reviews of my exhibitions. Or it can be seen as an expression of the oppression of women, who, when they married, would bring with them wardrobes of this kind; so-called marriage wardrobes, filled with linen that was part of their trousseau. However, faced with this opulence, it is also possible to dream wistfully of times when people’s homes were still decorated; even in peasant communities, people still held themselves in such regard that they designed and embellished their own rooms. Compared to the rooms of the Zoom attendees in their black shirts – what a celebration of life! The wardrobe is also a piece of painting and a hymn to colour and handicraft. To think that you can produce such a beautiful piece of furniture for next to nothing, just using paint, wood and your hands (more or less)! The people attending the seminar have not been specially chosen, and nothing about them has been exaggerated; they have been taken from one random snapshot. And yet to me they look like a dark vision of the future – is this really the way we live now?

Perhaps this sounds simplistic and unduly pessimistic. The picture can also be understood differently; for example, primarily as a collection of cell-like rooms, wardrobe shelves, Zoom windows and room windows, doors and screens – that is, as frames, cells and segments.

Or perhaps this way: the wardrobe is a self-portrait, and accordingly the Zoom attendees are other people out there, exterior to the self. And I am Dionysian, sumptuous and colourful, but also empty and alone etc.

Or: the wardrobe is a coffin. It is almost exactly the same shape.

Once when I was a child, I was looking for something on the top shelf of a rustic wardrobe, and the large, heavy piece of furniture toppled over with me inside it. I could have ended up dead!

Amelie von Wulffen, May 2023

(revised excerpt from the text for the exhibition des Pudel Kern, Paris)