Artist: Amedeo Polazzo

Exhibition title: whereabouts

Venue: Loggia, Munich, Germany

Date: May 14 – June 27, 2021

Photography: all images copyright and courtesy of the artist and Loggia, Munich

“The diaphanous front of the loggia presents the viewer in structured sections what is seen outside of it. For the moment of the distanced gaze, the framing transforms the landscape, the garden or the city panorama into an image, which, however, begins to dissolve as soon as the viewer approaches the parapet closely or even steps through the opening.”1

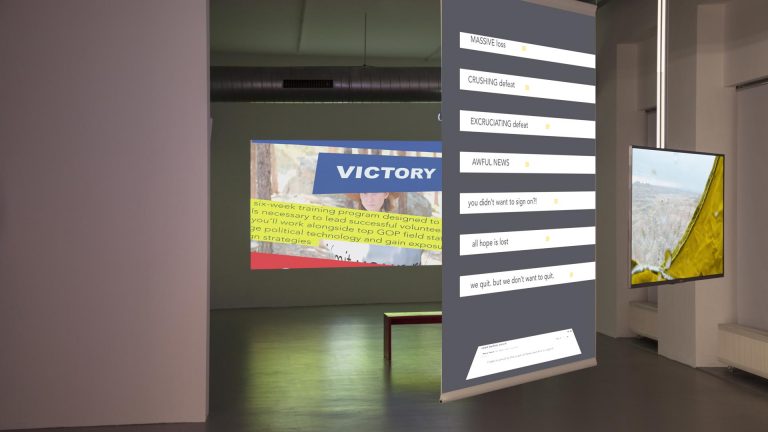

Horizontals and verticals overlap when looking out of the exhibition space, which – interrupted by its right-angled window division – then encounters another facade that is strictly geometrically divided into uniform cuboids. In architectural theory the loggia fulfils the role of a link between interior and exterior space. If one understands the exhibition space Loggia as a form of this type of space in the broadest sense, the enriching dialogue between Amedeo Polazzo’s wall painting and this space is explained. At Loggia, Munich, much more than the view into the real outside is structured and shown as such. In the artist’s paintings, interior and exterior continuously oscillate into each other, with the gaze never being directed in just one direction.

Polazzo invites the viewer into a liminal space within which the boundary between real space and illusionistic representation is softened.

The artist constructs immersive pictorial spaces on the basis of three condensing layers – architecture, time and the social dimension – whereby the intensive examination of the exhibition space is the starting point for further developments. Thus, on the one hand, he not only adopts peculiarities in the space, such as facing and wall projections, but continues these in the motif and, on top of that, investigates the function and history of the place. Hunter’s fence, clinker facade, remains of a flowered wallpaper, a yellow awning – post-war architecture meets Renaissance – columns, window grilles, a coffered ceiling, a round-arched window.

Finally, the question thrown into the room about the “whereabouts” is answered only fragmentarily – Polazzo’s settings elude clear localisation.

Self-referential aspects, such as subtle breaks with a uniform perspective, blurring and overlapping of layers of painting, further irritate the viewer when attempting to categorise them. So do smashed windows and half-lowered shutters possibly indicate the decline of retail – with the space of Loggia formerly used as retail space – is it a gloom that is spreading in many places in the inner cities? Or is it simply a slowly decaying residential building whose former residents prefer a modern house?

Amedeo Polazzo, whose biography is marked by changing residences and international exhibitions, traces his dynamic footsteps and translates them into visible complexity, formally and in terms of content, as a central gesture on the wall. The oil and pastel paintings on canvas emerge like close-ups that compressively interlock different pictorial levels; they heighten the complexity of the setting, while some of the motifs, through extreme zooming in, transfigure rather than clear the view.

Plasticity, a detailed perspective structure and a composition that extends over the entire space, characteristic of loggia paintings, are the hallmarks of Polazzo’s wall painting, while the pastel chalk diluted with water anticipates the limited lifetime inherent in his paintings and leaves an impression of fleetingness.

In their timelessness, the abandoned scenes seem removed from the real world. Vague moments – it remains unclear whether what is depicted is in the process of being built up or in the process of decaying. These, in Polazzo’s words, “moments of potential” give the images a liveliness without living protagonists, reinforced by incidental details such as stubbornly curling barbed wire, climbing plants and laundry fluttering in the wind. Underscoring an analogy between the world on the wall and reality, the artist repeatedly questions the understanding of space and time, putting its meaning into perspective precisely in this present, which is perceived as stagnant, where the presence of boundaries is more evident than ever.

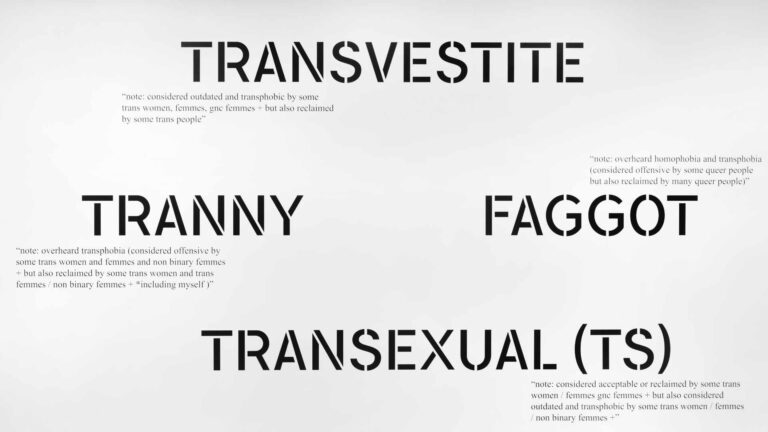

Indeed, borders have long been a core theme in Amedeo Polazzo’s work, which explains their multifaceted omnipresence in his pictorial inventions. Within this critical discourse, he addresses, among other things, questions of acceptance and rejection, of exclusion as well as the treatment of privilege, and focuses in particular on subliminal borders and exclusions, including garden fences and curtains. Emphasising an analogy between the world on the wall and reality, the artist repeatedly questions his understanding of space and time, putting its meaning into perspective precisely in this present, which is perceived to be at a standstill, where the presence of borders is more evident than ever.

Indeed, borders have long been a core theme in Amedeo Polazzo’s work, which explains their multifaceted omnipresence in his pictorial inventions. Within this critical discourse, he addresses, among other things, questions of acceptance, rejection and of exclusion as well as the treatment of privilege, and focuses in particular on subliminal borders and exclusions, as displayed in garden fences and curtains.

In analogy to how real boundaries appear differently depending on the perspective, Polazzo’s boundaries often remain ambivalent. Brick slips dance out of the brick row. Next door, the usually threatening barbed wire playfully flirts with a baroque twisted column in the style of Bernini, concealing with a euphemism its actual intention. At points like these, one may be reminded of the illusionistic fresco decoration of Italian loggias, determined by fantastic landscapes and mythologies.

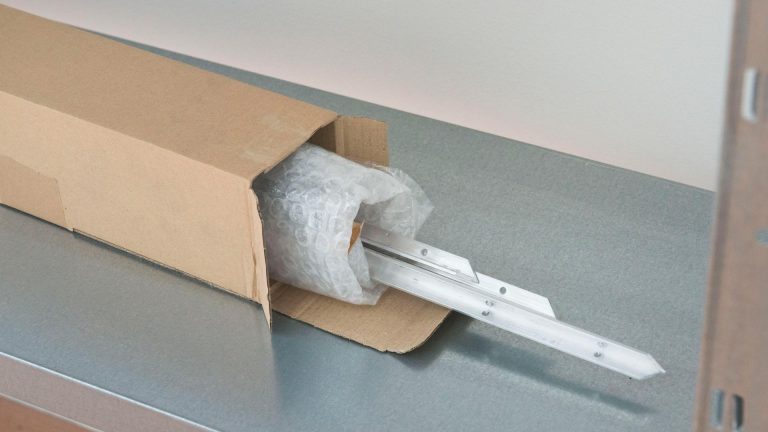

With all the obstacles, the ladder leaning against the wall suggests an obvious solution. For Loggia, Amedeo Polazzo adapts the reliably recurring motif of latticework in his pictorial spaces, as found in Italian Renaissance palaces, and designs a lattice element made of scagliola, an artistic technique often used for marquetry, in which marble is imitated by working plaster with the aid of pigments. In a similar way to the way Amedeo Polazzo uses characteristic aspects of different places for his panoramas, he takes over this imitation technique, reversing its use by presenting a supposedly viable object. Italy – Munich, as a permanent loop, this connection characterises the artist’s biography as well as his work. In this case, it is Munich, as the birthplace of the scagliola, that initiates its dissemination in Italy as well as forming a stopover to Polazzo’s next exhibition in Rome.2

Finally, in the second room at Loggia, nature has long since overgrown the parapet, ready to take the space from the viewers and leave them with a dystopian idea of crossing borders.

-Aline Fieker

[1] Allekotte, Jutta: Orte der Muße und Repräsentation. Zu Ausstattung und Funktion römischer Loggien (1470-1527). Bonn 2011, P.70 (unpublished).

[2] Wedekind, Wanja (2010): Scagliola – auf den Spuren zu möglichen Ursprüngen und Verbreitungen einer europäischen Kunsttechnik, in: Pursche, Jürgen (Ed.) „Stuck des 17. und 18. Jahrhunderts Geschichte – Geschichte – Technik – Erhaltung“. Internationale Fachtagung des Deutschen Nationalkomitees von ICOMOS in Zusammenarbeit mit der Bayerischen Verwaltung der staatlichen Schlösser, Gärten und Seen Würzburg, 4.-6.11.2008, München 2010: S. 213-221.