The sculptural work of Alexandra Bircken explores analogies between the human body and machines, examining the structures of protection, identity, and the extension of the individual. The Berlin-based artist combines a wide range of materials and techniques—often woven or knitted textiles—to probe the boundary between humans and their constructed environments. She also dissects everyday technical ob-jects with surgical precision, revealing the biomorphic qualities of machines. This dual approach results in an ambivalent body of work that is both cyborg-like and androgynous, questioning human behavior and desire, as well as the vulnerability of bodies in relation to technology.

The exhibition presents a selection of works created over the past decade, including several made specifically for this occasion.

The following remarks are excerpted from an interview with the artist (AB) by Paul Bernard (PB) and Selma Meuli (SM).

PB/SM: Many of the works in the exhibition directly reference the human body. What role does it play in your artistic practice?

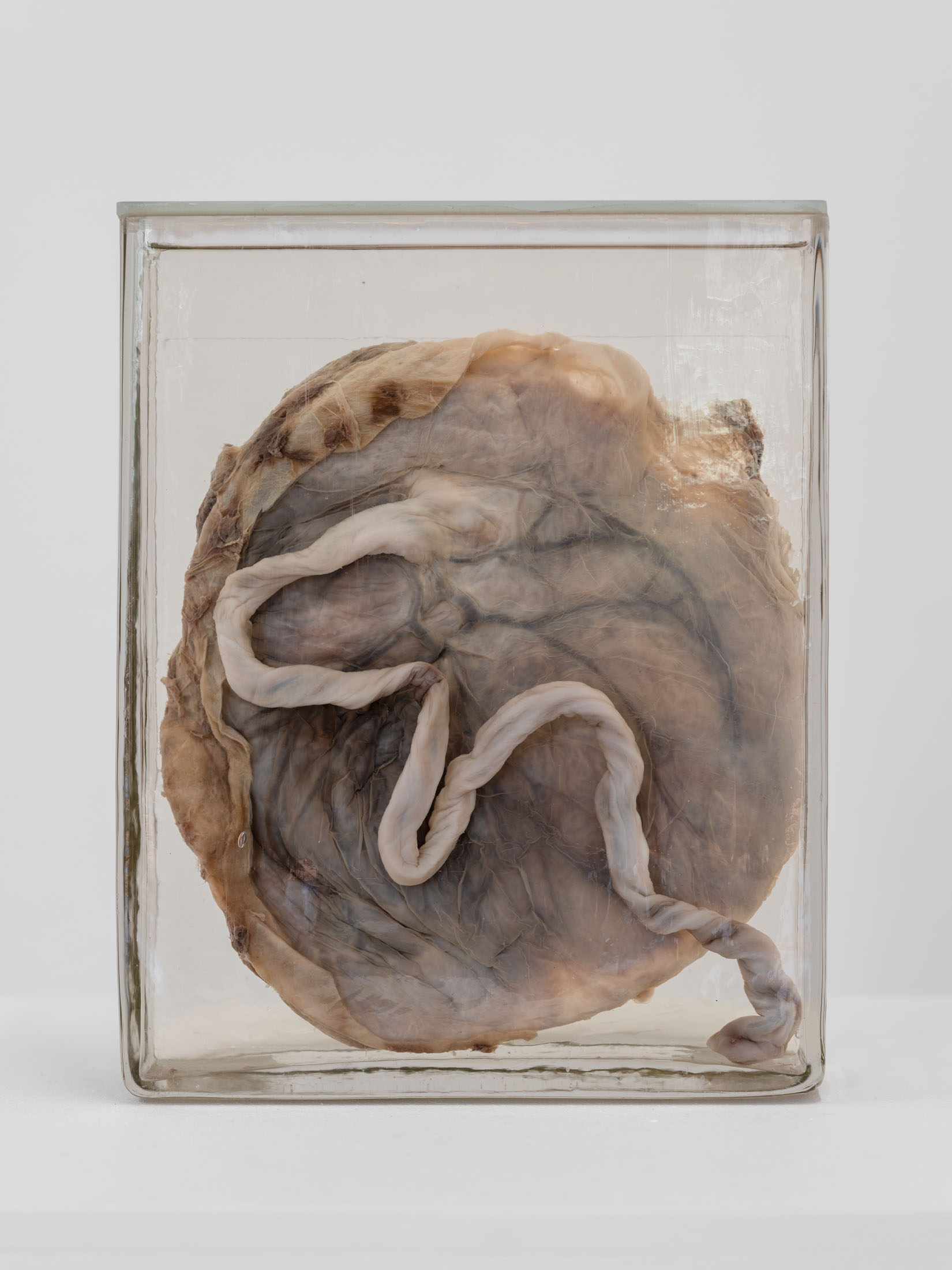

AB: My interest in the body and corporeality has personal roots: as a child, I underwent several intestinal surgeries and spent a lot of time alone in the hospital. This early, existential confrontation with my own body left a lasting impression. I began to perceive the body not only as my own but also as something abstract—an object that can be observed and examined. Beyond this biographical experience, I am interested in the body as a universal element: something that connects us all, since every human lives in and with a body, however diverse those bodies may be. Moreover, bodies are not only containers of inner life but also alter egos. And it is precisely this moment of otherness that is crucial in art. Sculpture always means to me: something stands opposite you; you relate to it. What does it do to you? What function does it have in the space or in relation to other objects, or within itself?

PB/SM: Beyond the body, skin in particular is a recurring theme in your work.

AB: Skin is the surface we see when we meet and observe each other. At the same time, it is the largest organ of the human body and reveals a great deal about the body’s condition. Skin is also something we clothe or cover and adorn. In this sense, it stands for representation as well as protection, vulnerability, and pain—all aspects I address in my artistic work.

PB/SM: Your work also shows a particular interest in machines, revea-ling their anthropomorphic character in certain places. How do you perceive this strange analogy between the body and the machine, the organic and the mechanical?

AB: Inside machines and engines, complex bundles of cables, known in German as «Kabelbäume,» (eng. cable harnesses) run through them. These highly branched structures resemble the human nervous or vascular system, both formally and functionally. Just as a network of fine veins extends from the heart through the human body, in a car, the battery serves as the central organ supplying power to electrical components—ignition, navigation system, radio, heating and cigarette lighter—through the cable harnesses. This transfer of organic principles to technical systems fascinates me and is a central motif in my work. The wall piece Efeu Elektro (2023) expresses this most clearly: the work consists of a rhizomatically grown cable harness that takes the form of an organic-technical sculpture.

PB/SM: This way of relating structures or systems that may seem foreign to each other appears to be a fundamental gesture in your artistic methodology. It is also present in your weaving works.

AB: In the works Picasso (2025) and Automatik (2024), both again made from car cables, I continue the approach of transferring systems—this time starting from the archaic technique of weaving. It’s less about analogies between body and machine and more about the encounter of different technical, cultural, and gender-specific regimes. Weaving is one of humanity’s oldest cultural techniques. In her «Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction» (1986), the American author Ursula K. Le Guin describes that the first human technology was not the weapon but a container: a bag, basket, or net used to gather food or catch fish. I found it particularly exciting to transfer a traditionally male-associated material—car cables, a symbol of an industrial, technicized world—into a textile technique that is historically female-dominated and much older. Despite the rapid technological progress that shapes our present, there are things that have hardly changed over millennia. Weaving is one of them— as is the technique of bronze casting, which I also use in several works in the exhibition, such as Trophy (2013), Chérie (2022) and Husky (2024).

PB/SM: The display in the corridor of the Parkett, showing snapshots, reference images, and material samples, seems like an intimate insight into your working process. Can you explain what is shown here?

AB: The showcases (Vitrine I-V, 2025), presented here for the first time, offer me a playful opportunity to relate collected impressions and materials to each other. The showcases thus form a kind of dynamic echo that reverberates back and forth between ongoing personal research and my works in the space. Similar to my sculptures, some showcases are more conceptually or thematically driven, while others suggest an associative approach—a kind of montage, in the cinematic sense of the word.

PB/SM: The horse is another recurring motif in the exhibition rooms. How do you approach this symbol of power?

AB: Recently, I completed PS (Horsepower) (2024)—a large-scale horse sculpture in public space. The nine-meter-long, painted stainless steel sculpture is placed at a heavily frequented traffic junction in Munich and represents a vertically split toy horse held together only by a hinge. Munich is considered a car city, yet the cityscape is also characterized by numerous equestrian statues—a sculpture genre widespread throughout the Western cultural sphere since antiquity, traditionally symbolizing power, military strength, and progress. With the exception of statues dedicated to the resistance fighter Jeanne d’Arc in some French cities, these representations almost exclusively serve the representation of patriarchal and male-dominated historical narratives.

Against this backdrop, PS (Horsepower), as well as the derived sculpture Gebrochenes Pferd (Broken Horse) (2024) featured in the exhibition, can be understood as an attempt to question and literally deconstruct this specific sculptural tradition. The horse, traditionally staged as the bearer of the rider, is rendered dysfunctional: slowed in its movement, stripped of its original dynamism. Only the connecting hinge hints at a potential moment of transformation. The idea of dysfunctionality, or the deliberate braking of established systems, runs through other works as well—pieces that also indirectly reference the motif of the horse, such as Gebrochenes Pferd (Broken Horse) (2023), Paystation (2025), and Ulysses (2025). These sculptures are composed of sawn and re-collaged car engines and motorcycles—machines that have replaced the horse as a means of transport—and thus reflect both a technical and symbolic reversal of historical narratives of progress. Finally, this theme continues in the work I (2025), created specifically for the exhibition: the serially moulded ceramic delineators are also a reference to the limitation of mobility. Positioned in a grid in the Salle Poma, they form points of reference in the space.

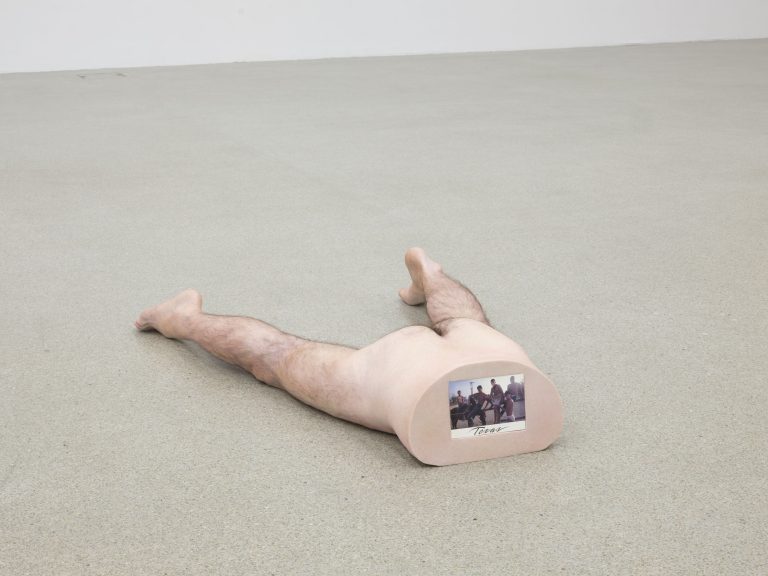

PB/SM: You also reference other symbols of authority in your work, such as the so-called «Merkel rhombus,» a gesture characteristic of the former German chancellor. This gesture appears notably in the work Doppelhaushälfte (2021), where you associate it with a dollhouse standing on two legs.

AB: In this figure, for which I combined various found objects—a mannequin leg, a branch, a dollhouse, a ball of yarn, and a hammer—it becomes clear how materials can generate new layers of meaning through their interaction. In Doppelhaushälfte, not only do different materials come together associatively, but also multiple cultural and political references. Angela Merkel’s hands, folded into a diamond shape in front of her stomach—incorporated into the sculpture as a photograph—have long become a recognizable symbol: a gesture of calm, control, and dignity in a political arena still dominated by white men. The German public—and especially the media—nicknamed Merkel «Mutti» (eng. «Mom»)—sometimes affectionately, sometimes ironically, and at times critically. The term alludes to her role as a seemingly maternal, calm, and caring leader, someone who knew how to listen and respond to people’s needs. This image of Merkel enters into a dialogue in the sculpture with a reference to Louise Bourgeois’ Femme Maison (eng. «Woman House»)—a series of drawings and paintings from the 1940s in which naked female bodies merge with houses, their heads concealed by architectural structures. In these iconic works, Bourgeois explores the traditional role of women as keepers of the home, while the outside world (and paid labor) remains gender-coded as male. The woman is enclosed and objectified in her corporeality; her identity vanishes behind architecture. This tension between body and symbol lies at the heart of the exhibition, as the chosen title «SomaSemaSoma» clearly suggests.

PB/SM: Can you tell us more about this title?

AB: The title refers to the ancient Greek words sōma (σῶμα), meaning «body,» and sēma (σῆμα), meaning «sign.» Both terms form the root of the discipline of semiotics, the study of signs. What interests me in this juxtaposition is the difficulty of translating between the body and language. Bodily experiences—sensory impressions, emotions, lived events—can never be fully conveyed through language. Language is an abstract, symbolic system that can only ever capture a fraction of what we experience physically and emotionally. This reduction creates an inevitable gap, a discrepancy between signifier and experience. It is this ambiguity—arising from the translation problem between body and meaning—that I explore in my sculptures. They negotiate the fragility and fragmentation of identity within a field of tension defined by materi-ality, symbolism, and political perceptions of the body.

PB/SM: This relationship between sculpture and language is also reflected in the titles you choose for your individual works. How do you approach that process?

AB: The titles don’t just name the works—they add another layer of meaning and visibility. It’s only through the title that many works can be fully experienced as independent pieces. Titles also allow me to playfully explore the contextualization or re-interpretation of the materials I use. Sometimes I choose humorous titles to cast the work in a different light and wordplays to evoke different meanings—Pinstrike (2021) or Paystation (2025) are typical examples. The title Ulysses (2025), for instance, refers on the one hand to the underlying material—a particular model of motorcycle—and on the other hand to the cultural and symbolic significance of the name. This interplay between reference and shifting meaning is something I find particularly fascinating.