Artists: Audrey Barker, Hanne Darboven, Moyra Davey, Jef Geys, Dan Graham, Pati Hill, Henrik Olesen, Cameron Rowland, Maud Sulter, B. Wurtz, Trisha Donnelly, Laurie Parsons, Cathy Wilkes

Exhibition title: A still life by Chardin

Organized by: Maxwell Graham

Venue: Lisson Gallery, London, UK

Date: July 7 – August 26, 2017

Photography: all images copyright and courtesy of the artists and Lisson Gallery, London

Jean-Siméon Chardin was born in 1699 in Paris, the son of a cabinet maker. He spent his entire life in Paris. His first wife died in the fifth year of their marriage. Both of his daughters died young, one at the age of three one at the age of one. His son, Jean-Pierre, also a painter, was kidnapped for a time by English pirates off the coast of Genoa, and drowned in a canal by his own will in Venice in 1772, at the age of 41. That same year Jean-Siméon Chardin had kidney stones.

In the hierarchy of genres, which was broadly accepted in the 18th century, history painting was ranked the highest, followed by portrait painting, then genre painting, then landscape painting, then animal painting, and then Still Life. More than anything else, Chardin painted still lives, often very slowly, and often at a very small scale. He painted wicker baskets, plumbs, breadcrumbs, pewter dishes, grapes, a silver goblet, glasses of water, a pestle and a mortar, walnuts, pewter jugs, earthenware pitchers, flasks, dead partridges, dead hares, dead salmon, dead rays, apples, Seville oranges, dead mallards, onions, leeks, turnips, straw, chestnuts, more knives, teapots, apricots, olives, wild strawberries, white carnations, coffee pots, a copper cistern, stone ledges and white tablecloths.

“Chardin is the irrefutable witness who makes other painters look like liars.” [1]

In 1728 Chardin was accepted into the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture. In 1742 he was quite ill and neither finished nor exhibited any paintings. In 1757 he moved into the Louvre, where he would spend the rest of his life. In 1770 he became the first painter to the king and the director of the Académie. He died on December 6, 1779 at the age of 80. In his estate he held approximately 5,638 livres of furniture.

Marcel Proust wrote in 1895: “Had you not already been unconsciously experiencing the pleasure that comes from looking at a humble scene or a still-life you would not have felt it in your heart when Chardin, in his imperative and brilliant language, conjured it up. Your consciousness was too inert to descend to his depth. Your awareness had to wait until Chardin entered into the scene to raise it to his level of pleasure. Then you recognized it and, for the first time appreciated it. If, when looking at Chardin, you can say to yourself, ‘This is intimate, this is comfortable, this is as living as a kitchen,’ then, when you are walking around a kitchen, you will say to yourself, ‘This is special, this is great, this is as beautiful as a Chardin.’ … In rooms where you see nothing but the expression of the banality of others, the reflection of your own boredom, Chardin enters like light, giving to each object its color, evoking from the eternal night that shrouded them all the essence of life, still or animated, with the meaning of its form, so striking to the eye, so obscure to the mind. … an ordinary piece of pottery is as beautiful as a precious stone. The painter has proclaimed the divine equality of all things before the spirit that contemplates them, the light that embellishes them.” [2]

Malraux wrote in 1951: “Chardin is not a minor 18th-century master who was more delicate than his rivals; like Corot he is a subtly imperious simplifier. His quiet talent demolished the baroque still-life of Holland and made decorators out of his contemporaries; in France, nothing can rival his work, from the death of Watteau to the Revolution.” [3]

Audrey Melville Barker had the seventh exhibition at Lisson Gallery, in London, from 1-30 December 1967. In a review of the exhibition in The Observer, Nigel Gosling wrote “The English would seem natural practitioners of the eerie art of the ‘Magic Box’ like those of the American Cornell. But few do, but several of Audrey Barker’s ‘Compartments’ have the right fragile mystery.” Earlier that year, Barker visited Joseph Cornell in Utopia Park, Queens, New York and he gave her two of his boxes. Barker was born in London in 1932. Tuberculosis contracted during the second world war, led to eight years of childhood in a hospital, lasting bone damage and arthritis. She made little work in the 1970s due to illness. She purchased and restored a mill which she developed into an art space and shelter for persons with disabilities. She refused invitations from the ICA in London because of a lack of proper accessibility to upper galleries. Barker’s work ranged from doll making to painting to exhibition organising, often focusing on alternative sensorial modes of communication. At an exhibition she conceived in 1997 at the Blackie Gallery in Liverpool, a fax machine was installed, on which visitors corresponded with Barker. These faxes were then displayed on the walls of the gallery.

In 1973, there was another exhibition at Lisson Gallery, by an American artist, which took place in the basement.

Pati Hill worked as a model, and was on the cover of Elle Magazine in 1950. She wrote numerous books of poetry, four novels including the seminal IMPOSSIBLE DREAMS and contributed on many occasions to the Paris Review.In 1962 she began collecting “informational art.” Sometime after that “I began collecting objects. I kept them in a laundry hamper and when the hamper overflowed I would take them to a copier in a nearby town and record the ones that still intrigued me, then throw the originals away or put them back into circulation.” In 1975 she had her first exhibition at Kornblee Gallery in New York. She was married to the New York gallerist Paul Bianchini, who hosted an interesting exhibition in 1965. About the copy machine Hill observed “It is the side of your subject that you do not see that is reproduced.” [4]

“When I first decided on this box of photos as something to exhibit, I was excited. Having had increasingly ambivalent feelings about exhibiting a fixed object in a fixed environment, I was searching for new entrances on a given situation. This would be the same old song, but because it was so disarmingly personal and expository, it would involve me more completely in the situation.” Laurie Parsons, 1991

[1] Green, Julien. Oeuvres completes, III, pp.1348-9, 1949

[2] Proust, Marcel. “Chardin: The Essence of Things” trans. Mina Curtiss, in Against Sainte-Beuve and Other Essays, ed. John Sturrock, pp.100-107, 1994

[3] Rosenberg, Pierre. Chardin, pp.234, 2000

[4] Hill, Pati. Letters to Jill : a catalogue and some notes on copying, pp. 18, 22, 118, 1979

A still life by Chardin, 2017, exhibition view, Lisson Gallery, London

A still life by Chardin, 2017, exhibition view, Lisson Gallery, London

A still life by Chardin, 2017, exhibition view, Lisson Gallery, London

A still life by Chardin, 2017, exhibition view, Lisson Gallery, London

A still life by Chardin, 2017, exhibition view, Lisson Gallery, London

A still life by Chardin, 2017, exhibition view, Lisson Gallery, London

A still life by Chardin, 2017, exhibition view, Lisson Gallery, London

A still life by Chardin, 2017, exhibition view, Lisson Gallery, London

A still life by Chardin, 2017, exhibition view, Lisson Gallery, London

A still life by Chardin, 2017, exhibition view, Lisson Gallery, London

A still life by Chardin, 2017, exhibition view, Lisson Gallery, London

A still life by Chardin, 2017, exhibition view, Lisson Gallery, London

A still life by Chardin, 2017, exhibition view, Lisson Gallery, London

A still life by Chardin, 2017, exhibition view, Lisson Gallery, London

Archival Exhibition Documentation, Photographs by Jef Geys

Archival Exhibition Documentation, Photographs by Nicholas Logsdail, Michael Asher. “My proposal for this space was to cut an architectural reveal, 1/4 inch wide and 1 1/2 inches deep, into the wall at floor level, around the perimeter of this room. The architectural reveal began and ended at the entry/exit passageway, without turning into the passageway, since that functioned as a transition zone between two exhibition spaces.”

Archival Exhibition Documentation, Audrey Barker

Laurie Parsons, Box of Photos, 1991, Assorted materials, 14 x 43.2 x 68.6 cm, 5 1/2 x 17 x 27 in

Laurie Parsons, Box of Photos, 1991, Assorted materials, 14 x 43.2 x 68.6 cm, 5 1/2 x 17 x 27 in

B. Wurtz, Stereo, 1986, Wood, metal, 50.2 x 55.2 x 17.8 cm, 19 3/4 x 21 3/4 x 7 in

B. Wurtz, Stereo, 1986, Wood, metal, 50.2 x 55.2 x 17.8 cm, 19 3/4 x 21 3/4 x 7 in

Moyra Davey, Hoboken, 1999-2017, 4 c-prints, tape, postage, and ink, Overall dimensions: 50.8 x 124.5 cm and 50.8 x 35.6 cm, Overall dimensions: 20 x 49 in and 20 x 14 in

Moyra Davey, Hoboken, 1999-2017, 4 c-prints, tape, postage, and ink, Overall dimensions: 50.8 x 124.5 cm and 50.8 x 35.6 cm, Overall dimensions: 20 x 49 in and 20 x 14 in

Moyra Davey, Hoboken, 1999-2017, 4 c-prints, tape, postage, and ink, Overall dimensions: 50.8 x 124.5 cm and 50.8 x 35.6 cm, Overall dimensions: 20 x 49 in and 20 x 14 in

Henrik Olesen, Untitled, 2017, Wood, acrylic, screws, 199 x 5.5 x 4 cm, 78 3/8 x 2 1/8 x 1 5/8 in

Henrik Olesen, Untitled, 2017, Wood, acrylic, screws, 199 x 5.5 x 4 cm, 78 3/8 x 2 1/8 x 1 5/8 in

Audrey Barker, A Box for Nicholas Roberts, 1967, Mixed media, 53.3 x 45.7 cm, 21 x 18 in

Audrey Barker, A Box for Nicholas Roberts, 1967, Mixed media, 53.3 x 45.7 cm, 21 x 18 in

Dan Graham, Model for Triangular Pavilion with Shoji Screen, 1990, Aluminium, glass and maple wood, 87 x 87.5 x 76 cm, 34 2/8 x 34 4/8 x 29 7/8 in

Trisha Donnelly, Astoria 36, 2014, Projection of digital images, Dimensions variable

B. Wurtz, Untitled (Brackets and shelf #1), 1986, Wood, metal brackets, wire, 45.7 x 24.8 x 27.9 cm, 18 x 9 3/4 x 11 in

B. Wurtz, Untitled (Brackets and shelf #1), 1986, Wood, metal brackets, wire, 45.7 x 24.8 x 27.9 cm, 18 x 9 3/4 x 11 in

A still life by Chardin, 2017, exhibition view, Lisson Gallery, London

Pati Hill, Untitled (paving stone, Versailles), c. 1981, Black and white photocopier print, 29.9 x 21 cm, 11 3/4 x 8 1/4 inches

Pati Hill, Untitled (sleeve, from the series Photocopied Garments), c.1976, Black and white photocopier print, 35.6 x 21.6 cm, 14 x 8 1/2 in

Pati Hill, Untitled (fragment of Grand Trianon, Versailles), c. 1981, Black and white photocopier print, 21.6 x 35.6 cm, 8 1/2 x 14 in

Cameron Rowland, Loot, 2013, Cut and dented copper tube, cardboard box, 35.6 x 50.8 x 30.5 cm, 14 x 20 x 12 in. At some point basic utilities like electricity and water were services controlled by the state, because they relied so heavily of public infrastructure. More and more these flows are valved by private corporations. Abandoned buildings and sometimes those still used, are broken into and stripped of their copper piping. This is then sold to scrap yards where it is cut down and smaller rods are inserted into thicker ones to make the densest bulk. Rowland bought Loot as is. All of these transactions are extra-legal activities. Copper has a function, its base material has an inherent use value, just as gold and diamonds also carry utilitarian properties.

Cameron Rowland, Loot, 2013, Cut and dented copper tube, cardboard box, 35.6 x 50.8 x 30.5 cm, 14 x 20 x 12 in. At some point basic utilities like electricity and water were services controlled by the state, because they relied so heavily of public infrastructure. More and more these flows are valved by private corporations. Abandoned buildings and sometimes those still used, are broken into and stripped of their copper piping. This is then sold to scrap yards where it is cut down and smaller rods are inserted into thicker ones to make the densest bulk. Rowland bought Loot as is. All of these transactions are extra-legal activities. Copper has a function, its base material has an inherent use value, just as gold and diamonds also carry utilitarian properties.

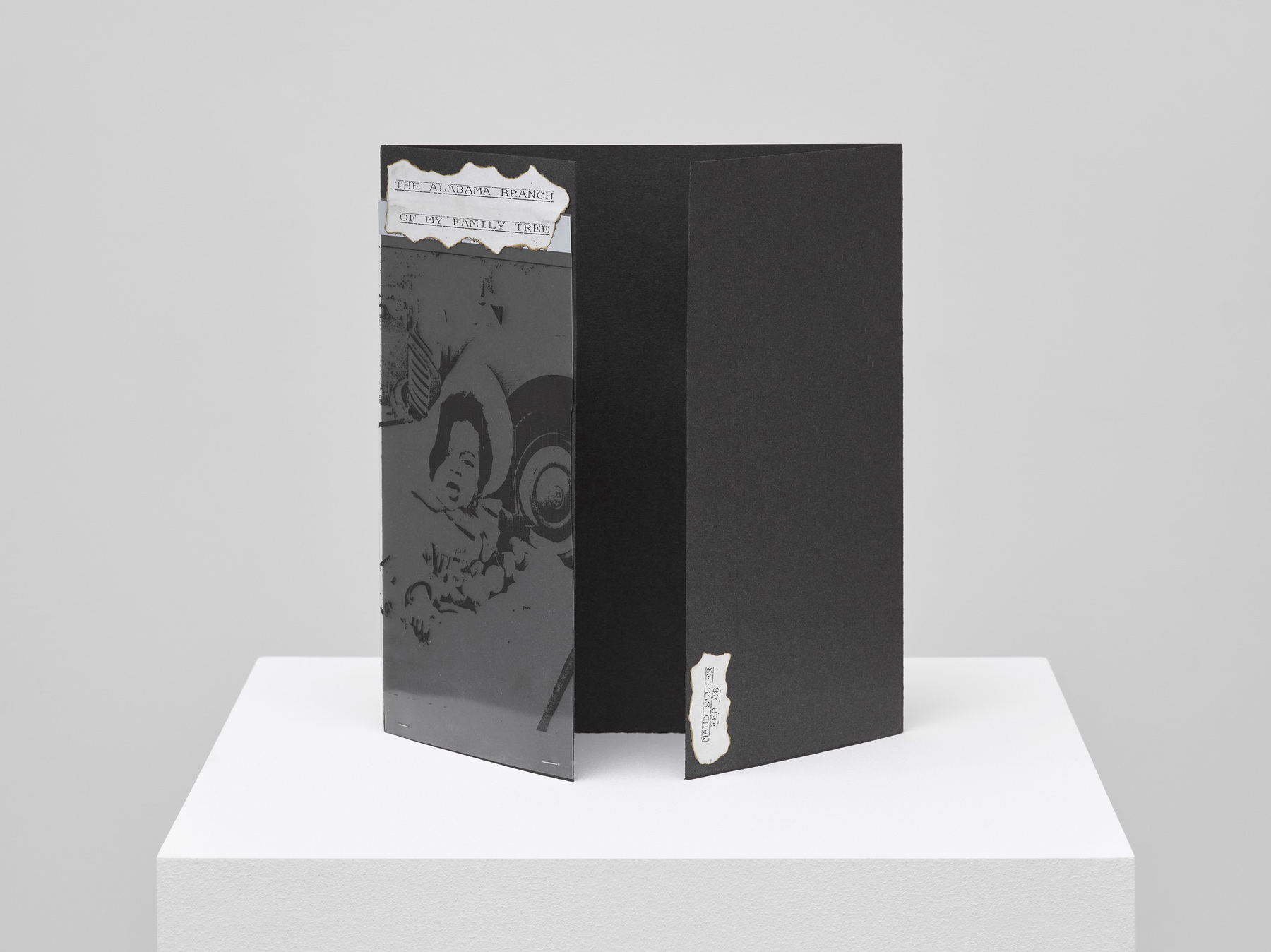

Maud Sulter, The Alabama Branch of My Family Tree, 1988, Folded card and burnt paper, 23 x 2.1 cm, 9 x 7/8 in

Hanne Darboven, Ohne Titel, c. 1985, Xerox and pen on paper, 22 x 28 cm, 8 5/8 x 11 in

A still life by Chardin, 2017, exhibition view, Lisson Gallery, London

Pati Hill, Untitled (paper bag), c. 1977-1979, Black and white photocopier print, 27.9 x 21.6 cm, 11 x 8 1/2 inches

Pati Hill, Untitled (paper bag printed with fruit image), c. 1977-1979, Black and white photocopier print, 27.9 x 21.6 cm, 11 x 8 1/2 inches

Henrik Olesen, Untitled, 2017, Wood, acrylic, screws, 56 x 167 x 3.5 cm, 22 x 65 3/4 x 1 3/8 in

Jef Geys, Snake Camouflage, 1986, Cardboard box, faux snake skin wrapping paper, 60 x 40 x 28 cm, 23 5/8 x 15 3/4 x 11 in

Jef Geys, Snake Camouflage, 1986, Cardboard box, faux snake skin wrapping paper, 60 x 40 x 28 cm, 23 5/8 x 15 3/4 x 11 in

Audrey Barker, Untitled, 1964, Newspaper, ribbon, paint on wood and galvanised steel, 31.3 x 27 cm, 12 3/8 x 10 5/8 in

Pati Hill, Untitled (white gloves, from the series Photocopied Garments), c. 1976, Black and white photocopier print, 21 x 34.9 cm, 8 1/4 x 13 3/4 in

Hanne Darboven, Ohne Titel, c. 1985, Pen on paper, 13 x 8 cm, 5 1/8 x 3 1/8 in

B. Wurtz, Untitled (Shelf), 1986, Wood, metal, screws, 22.9 x 22.2 x 10.2 cm, 9 x 8 3/4 x 4 in