Fountains control the movement and cycle of water. We are surrounded by mundane structures that move water, often hidden from sight: pumps, pipes and sewage systems. By contrast, a fountain is visible and exuberant: it can stimulate, delight, and stir the erotic. In this exhibition, the fountain becomes a space to transform dreams and desires into a dripping, spattering, sparkling form.

Fountains have given people pleasure since ancient times, across civilisations and cultures. The Ancient Romans venerated water and delighted in its appearance and its movement through an unseen power. The Persian rulers of the Middle Ages built elaborate fountains in their palaces and gardens to represent paradise as described in the Qu’ran. King Louis XIV of France employed fountains at Versailles as a visual representation of his dominance over nature. In the 19th century, fountains became part of civic infrastructures, providing clean drinking water to urban populations and thereby becoming important meeting places – akin to the contemporary cliché of the office water cooler where news and gossip is spread. Today, fountains mostly serve a decorative purpose, but remain in public spaces and private gardens.

“The Fountain Show” looks at the fountain as an artistic object. In 1917, Marcel Duchamp created the most famous ‘fountain’ in Western art history, the readymade urinal (1917). The work, simply titled Fountain, played with the art historical symbolism of the decorative fountain and overturned previous ideas of what makes art. The works gathered in this exhibition stand in a long line of fountains that have been depicted or designed by artists and asks what the fountain stands for today.

Anita Esfandiari

The Persian epic Haft Peykar (1197) centers on the life of the powerful hunter king Bahrām-e Gūr and his seven princess brides. In an early episode of this erotic poem, the slave girl Feṭna is sentenced to death for challenging the king but manages to escape. She then dedicates her life to taking revenge on Bahrām-e Gūr.

Anita Esfandiari’s sculptural painting Gave to the cypress a rosy shade of the redbud; and to the tulip gave the stature of a bambuseae (2023) re-imagines the Haft Peykar from Feṭna’s perspective and brings her story into the present day as an icon of strength and perseverance. The twelve painted panels show Feṭna carrying a lamb up and down an endless staircase, hiding behind a curtain and riding a motorcycle into the distance. Painted only from the inside, the cylindrical structure rotates continuously and offers the viewer an obstructed view of the tableau.

In Esfandiari’s home country of Iran, fountains have historically carried great significance as gathering places and are now largely neglected as the government curtails public freedoms. She treats the fountain as an artistic structure that carries and transforms matter, replacing the element of water with images and narratives. In the back space of the exhibition, a group of three sculptures by Esfandiari strips the fountain down to its basic form, showing its power as a symbol even when devoid of its substance.

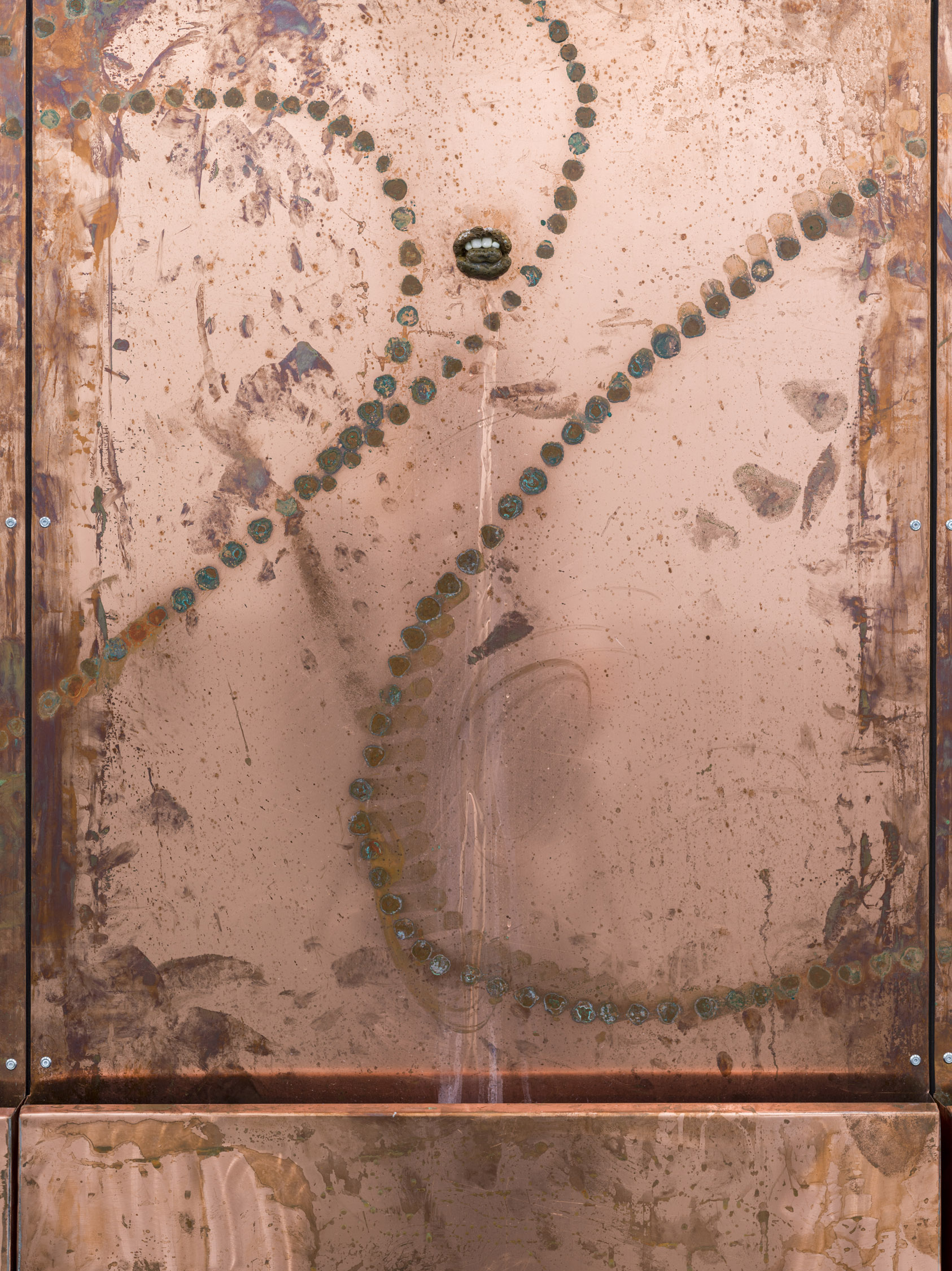

Lou Masduraud

The Cento fontane flows in the garden of the Villa d’Este, on the outskirts of Rome. This impressive Renaissance fountain is a long wall with hundreds of stone orifices — shaped like lilies, dragons, eagles and human faces — spouting water across three levels. The fountain is on the scale of an architectural monument and was built as a demonstration of power and wealth. Today, it is open to the public and home to an ecosystem of plants and animals.

Lou Masduraud, an artist with a long-standing research into the fountain as a political object, modeled her work Fontaines (I-VIII) (2023) after the Cento fontane. Each of its eight panels bears a disembodied, leaking mouth filled with shells, pearls and corals. The copper surface is decorated with floral drawings made using pickle slices, their vinegar leaving traces on the bronze through oxidation. The work emphasizes how a fountain is alive, constantly transforming and exchanging with its surroundings.

For Masduraud, the fountain’s visual splendour masks a darker underbelly. She refers to the fountain’s relationship with the urinal, which she calls the fountain’s ‘hidden opposite’. The fountain confiscates water, which should be a common good, to make a spectacle of it, while concealing the hidden pipes and sewers underneath. Her practice examines the opposition between public and private, cleanliness and purity that is central to the administration of bodies and populations up until this day.

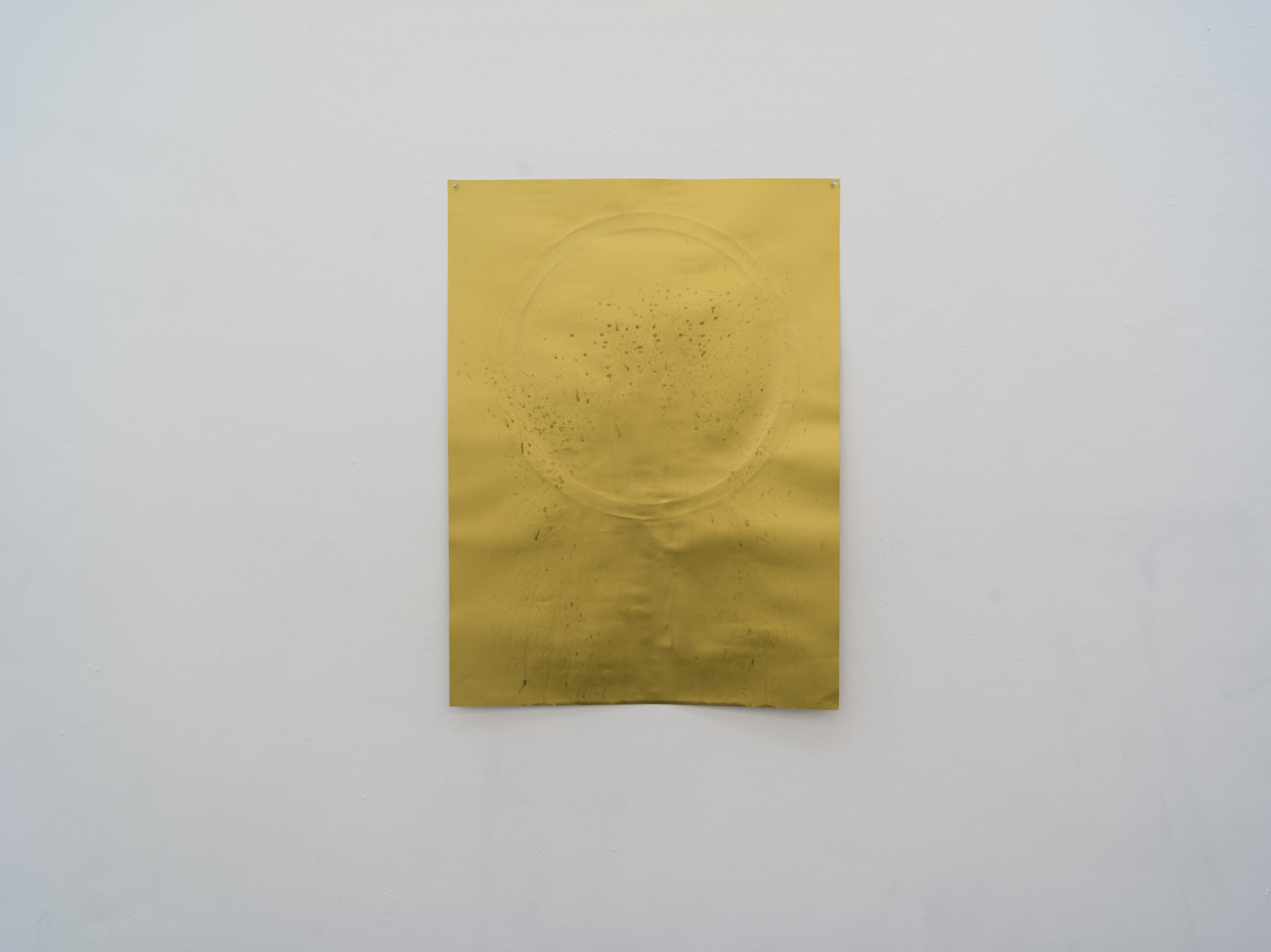

Sophie Nys

In 89 locations across the city of Zurich, you can find a modernist drinking fountain designed by Alfred Aebersold. Built in the 1970s with the backdrop of the Cold War, the network of fountains is in fact a civil defense infrastructure designed to provide clean drinking water to the population if the regular water supply becomes contaminated. The fountains are like secret agents, evidence of a constant threat hidden in plain sight.

Sophie Nys’ series Frottage (2019) was made by pressing the edge of this fountain’s basin into golden sheets of paper, creating a circular embossing. Each print is marked with the urine of a colleague or friend, referring to bodily functions to connect the object of the fountain to that of the urinal – a clear nod to Marcel Duchamp’s iconic readymade. As is typical for Nys, these works take an object of everyday life and reposition it through a process of abstraction and intervention. The artist thereby mobilises latent political meanings and subverts conventions of conceptual art.

Frottage is part of a larger body of work inspired by Aebersold’s fountains. Nys’ book “Divided we stand, together we fall” contains photographs she took of each of the fountains, combined with texts by artist Leila Peacock.

Kasia Fudakowski

A clepsydra is an ancient device for keeping time using water. Its mechanism is simple: water drips from one vessel with a small hole down into another. During antiquity, it was primarily used to limit speaking time during court proceedings. We can imagine the tense atmosphere created by the clepsydra, with the steady sound of dripping water accompanying the words of each speaker. For the philosopher Seneca, the clepsydra functioned as an ominous, universal reminder of the finiteness of life itself, “each successive drop an irretrievable loss”.

Kasia Fudakowski’s Watch what you say (2019-24) is a speech-activated fountain which essentially converts words into water. If you speak into the microphone, water will drip into the bucket, threatening to overflow if too many words are spoken. This work emerged from a film series Fudakowski created between 2016-2021 with a dystopian premise; in the near future, scientists discover a correlation between the dramatically rising sea-levels, and the amount of words which are spoken.

A limit on speech is proposed to mitigate its harmful impact. With freedom of speech, suddenly and directly, in conflict with the health of our environment, being able to measure and account for each word is crucial. And while there is an undeniable joy to be had in literally ’speaking water’, the association with the damage words can cause is unavoidable. The fountain here becomes a way to link social and ecological realities, using a bleak kind of humour to implicate each of us within them.

Aline Bouvy

In 1915, the Newark Museum of Art exhibited three porcelain toilets as part of an exhibition. Its director said that “the genius and skill which have gone into the adornment and perfecting of familiar household objects should receive the same recognition as do now the genius and skill of painting in oils.” Two years later, Marcel Duchamp submitted a porcelain urinal entitled Fountain to an exhibition of the Society of Independent Artists in New York, under the pseudonym R. Mutt. The work was not accepted into the exhibition, setting in motion a succession of events that ushered in an entirely new framework for the art world as we know it today.

The aesthetic potential of the urinal is brought to the fore by Aline Bouvy’s wall-based jesmonite sculptures. They blend into the architecture of the exhibition space, like stucco decorations in a perverted palace. In her practice, Bouvy looks at social norms and the moral codes that permeate from public space into private life. This work provokes the audience to ask themselves which bodily functions – and whose – are allowed in public space. Bouvy literally upturns a masculine-coded object and gives it the shape of a vulva, in what Denis Gielen has called a “queer reversal”. The work looks at the hierarchical distinctions between art, design, and decoration, echoing the position of the fountain throughout art history – not least of all Duchamp’s.

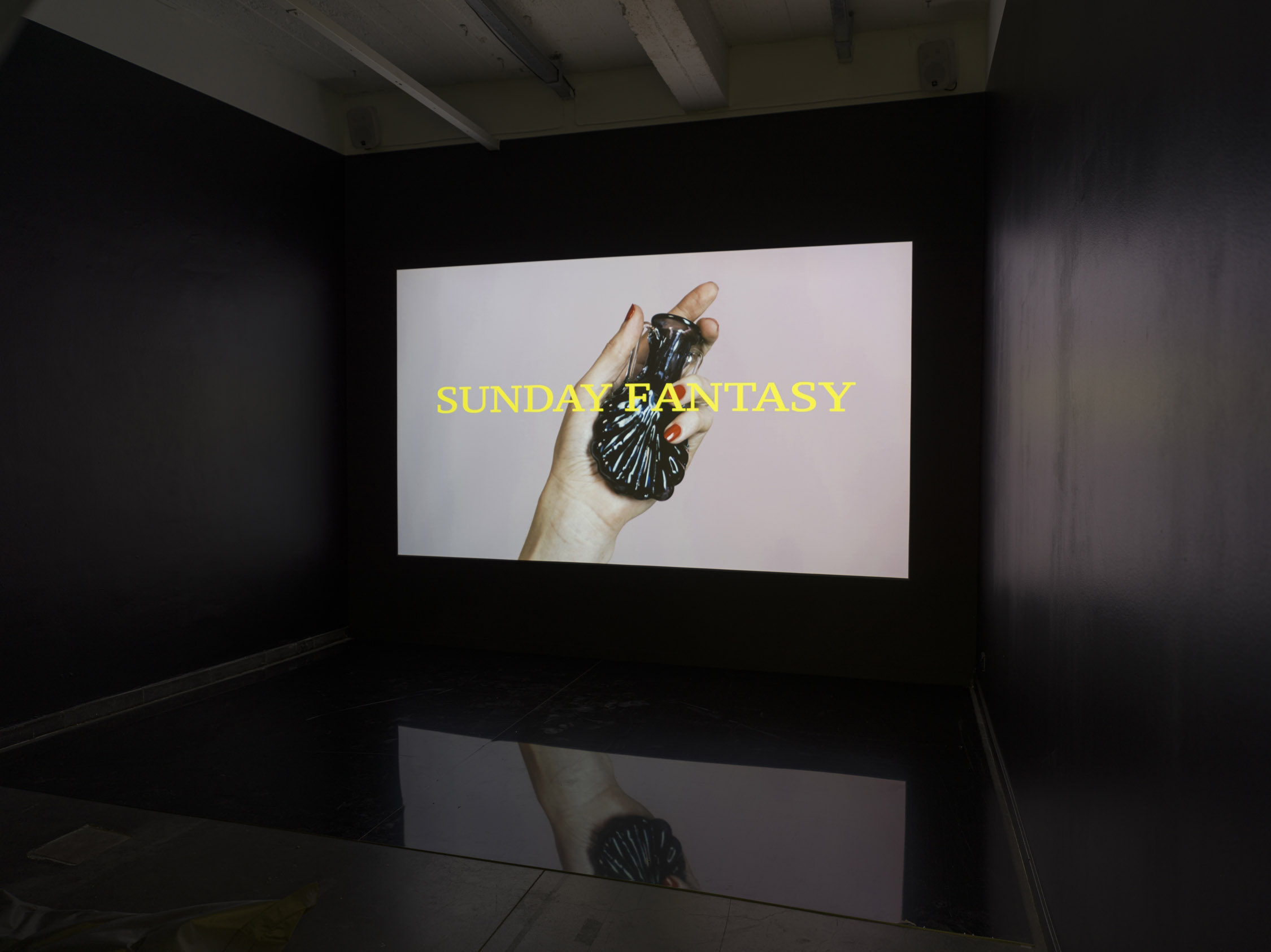

Zoe Williams

The Ancient Romans developed hydraulic engineering techniques that allowed them to construct elaborate fountain systems to provide clean water to cities. With their rise to power and immense wealth, opulence was not far behind, and the Romans liked to pamper themselves with balms, ointments and perfume, which was kept in hand-blown glass vessels. Emperor Nero is said to have installed silver pipes in his villa to spritz dinner guests with rosewater.

Zoe Williams’ film Sunday Fantasy (2019) uses the form of a glass shell shaped bottle as a catalyst for action. The object is inspired by a Roman perfume bottle that the artist discovered in the British Museum’s collection, which she imagined belonged to a lesbian Roman priestess, who used the bottle to distil and realise her erotic fantasies.

Zoe Williams and co-director Amy Gwatkin along with two artist friends Deniz Ünal and Nadja Voorham, each wrote a script for the film’s present-day protagonist Veronica Malaise, who finds the perfume bottle on a Thames Estuary beach. Sunday Fantasy brings the writers’ own fantasies to life in four chapters, using the magical bottle as a conduit to build a world of heightened sexuality centering female and queer desire.

Williams works across a range of mediums, creating immersive environments. Her sculptures continue her exploration of the shifting use values of objects and rituals through history. Fondant desires (piss in boots) nightstand/Tuberose obscenity chamber pot/Vice’s hand mirror and Fondant golden shower of Baubo mirror form an erotically charged vanity room, with shapes and textures that suggest lubrication and release. Together with Sunday Fantasy, they hone in on the erotic suggestion of the fountain, spilling out excess and desire.

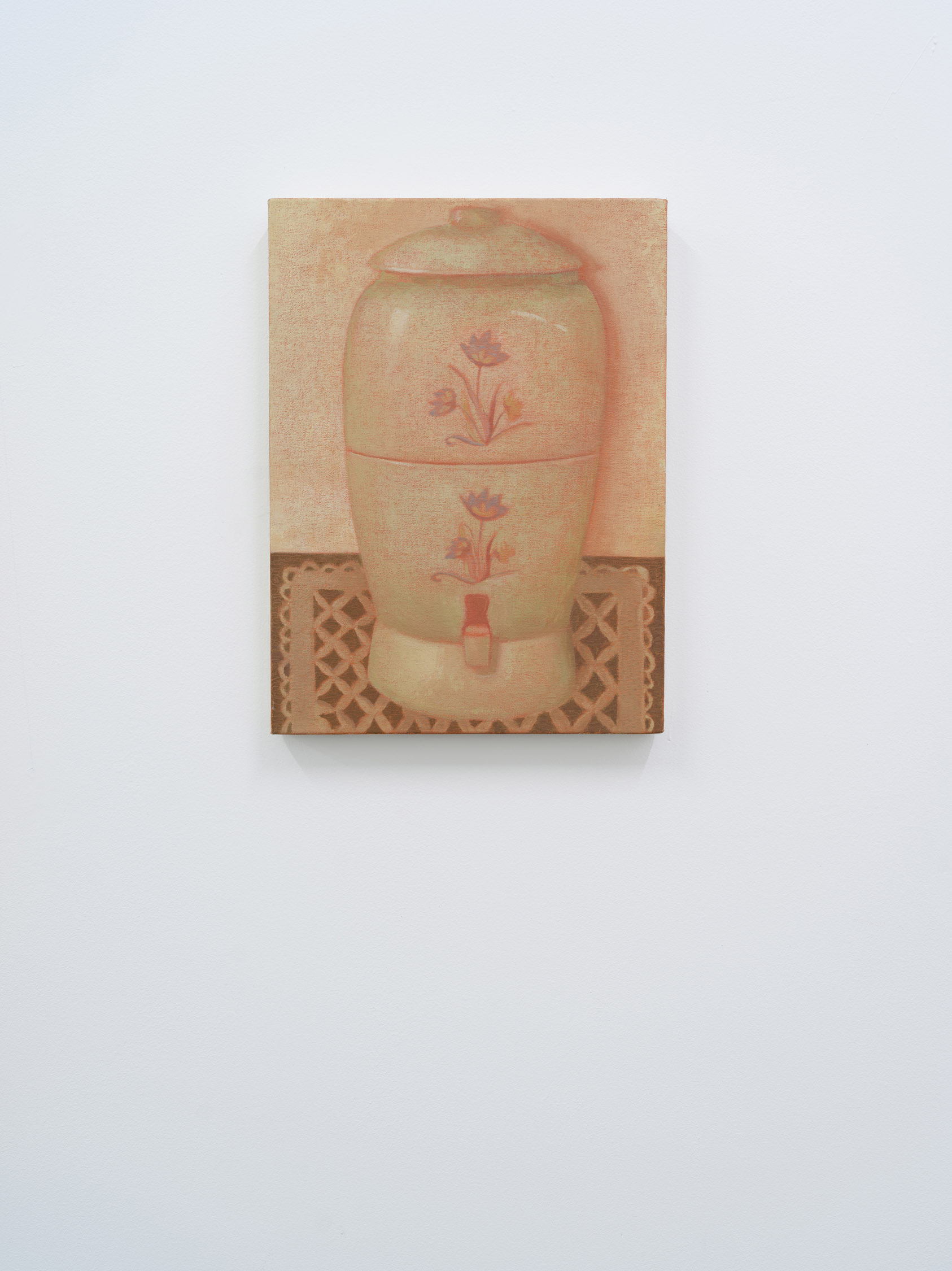

Paula Siebra

The Fountain of Youth is a legendary spring purported to grant eternal youth and immortality to those who drink or bathe in its waters. It was popularized by myths and folklore throughout history and depicted many times over in paintings and sculptures. A notable interpretation was painted by Lucas Cranach the Elder in 1546, who based his fairy tale tableau on the real bathing practices of the Middle Ages.

Paula Siebra is drawn to archetypes: objects that are recognizable everywhere and by everyone. While firmly rooted in the simplicity of everyday life, the soft contours and washed-out colors of her paintings give them a dream-like quality. Siebra departs from the culture of the Brazilian Northeast, incorporating aesthetics of native folk art while also referring to the canonical painting genres of still life and landscape.

For Siebra, fountains are universal symbols. Her fountain in Fonte is simple and to the point, with white beads of water frozen in time – but it also alludes to the art historical weight of the fountain and its myriad depictions. Two other paintings represent the fountain as a utilitarian object and natural source respectively. In all three works, Siebra positions the fountain as a powerful symbol of life and transformation.

David Bernstein

The mikvah is a Jewish ritual bath built directly into the ground. Its use is tied to moments of transition: menstruation, childbirth, marriage. Although it has historically been linked to conservative ideas about feminine impurity, some feminist and queer Jews have also reclaimed the mikvah to mark other moments in their lives, such as gender transition and recovery from illness. Civilizations across the globe have developed water-bearing structures for rituals of purification, such as Turkish hammams or Japanese baths.

David Bernstein’s Hammama’s Boy (2019) is a portable wooden tub inspired by the structure of a Japanese ofuro and the tradition of the mikvah. Bernstein’s practice is driven by “Judeo-Futurism”: his works reclaim historical symbols and place them into joyful and subversive fantasies. Hammama’s Boy embraces the derogatory term of a “mama’s boy” and pays homage to the feminine capacity for renewal that the mikvah symbolises. The sides of the tub bear engravings of poems written from conversations with the artists’ mother and grandmother, who share a love of taking baths.

Visitors of all ages are warmly invited to climb into the tub. As a nod to childhood, for this exhibition the water has been replaced by plastic balls.

Jay Tan

Maybe you remember the Herbal Essences commercials of the early 2000’s: a beautiful woman with vaguely Asian features has an orgasmic experience while shampooing her hair in a tropical waterfall, with a pair of monkeys overlooking the scene.

Jay Tan’s work Soap Berries at Scholar’s Rock (2021) retools these elements as a clanky kinetic sculpture, an indulgent insurgent scene of collective pleasure, mania, and liberation. Tan’s practice is born from a desire to create environments and objects that jangle and flit between media-soaked dreams, memories, and alternate realities. Their works are seductive, loud, shiny, and intricate. They embrace pop cultural references and aesthetics of home engineering projects to critique western classical notions of taste, beauty, and ornament.

Soap Berries at Scholar’s Rock (2021) is a writing desk turned into a diorama featuring a mechanical waterfall that visitors can activate. This paradisiac landscape is inhabited by a variety of clay self-portrait figurines – washing their hair, riding a motorcycle, climbing, and copulating. Tan subverts the art historical tradition of the fountain and gets to the heart of the ambiguity it carries as an object that can be decorative, monumental, domestic, functional, frivolous – a collapsing of signifiers to unsettle assumptions of meaning and use.

Chloé Op de Beeck

Up until early 2024, there was a public fountain located on the Schuttersvest, marking the entrance of the city of Mechelen. It had a simple design, a round basin with jets of water arranged in a spiral to form a dome-like shape. It had already been emptied of water for a few years before it was decommissioned and destroyed by the city, which cited the high cost of restoring and maintaining the fountain. Instead, they will build a green area with flowers and benches.

Chloé Op de Beeck grew up in Mechelen and rediscovered her hometown as an adult on long walks. Her work is characterised by a minimal, documentary-like approach, where she focuses on public space and the way people behave in it. She often captures the ambiguity between the natural and the artificial that defines contemporary environments. In her video work However (2019), the artist shows the Schuttersvest fountain at the precise minute it begins to spray water in the early morning, a rarely witnessed but euphoric moment.

Virginia Overton

In the United States, many corporate logos and names of businesses on skyscraper facades are predominantly created with heavy aluminum. The logos and lettering are almost sculptural in their size and thickness. Often, businesses change or update logos and thus the original aluminum signage becomes obsolete; and as these signs are removed and replaced, the aluminum signage is often cut up and discarded.

In the work Untitled (cascade), Virginia Overton has reactivated this discarded aluminum by reassembling the material into a sculpture. She utilizes deconstructed aluminum letters to form water basins for a cascading fountain supported by ladders and sandbags. Acutely aware of the footprint left from material waste, Overton gives new purpose to a material which is otherwise considered no longer of use, offering the viewer an alternative perspective of the potentiality of the discarded.