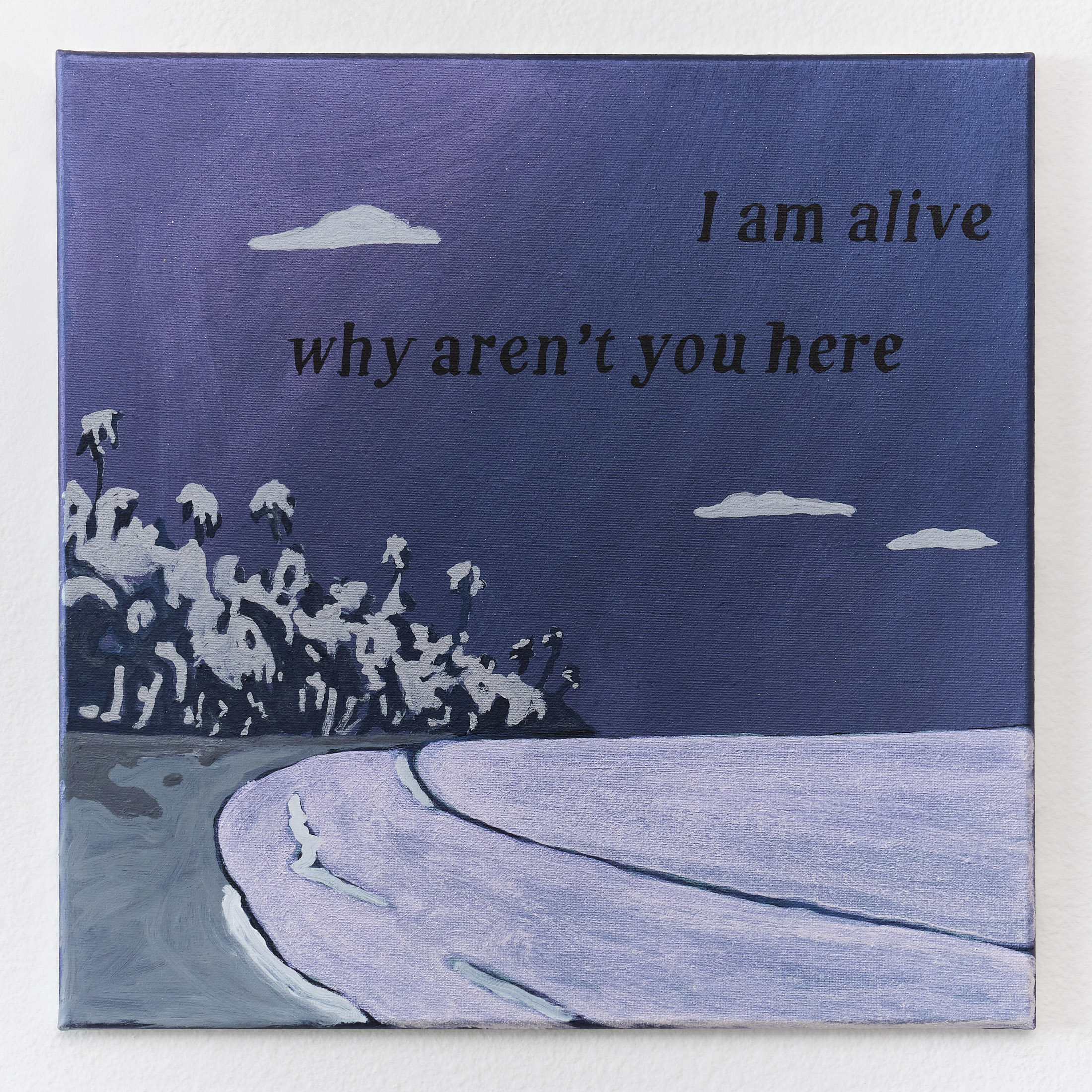

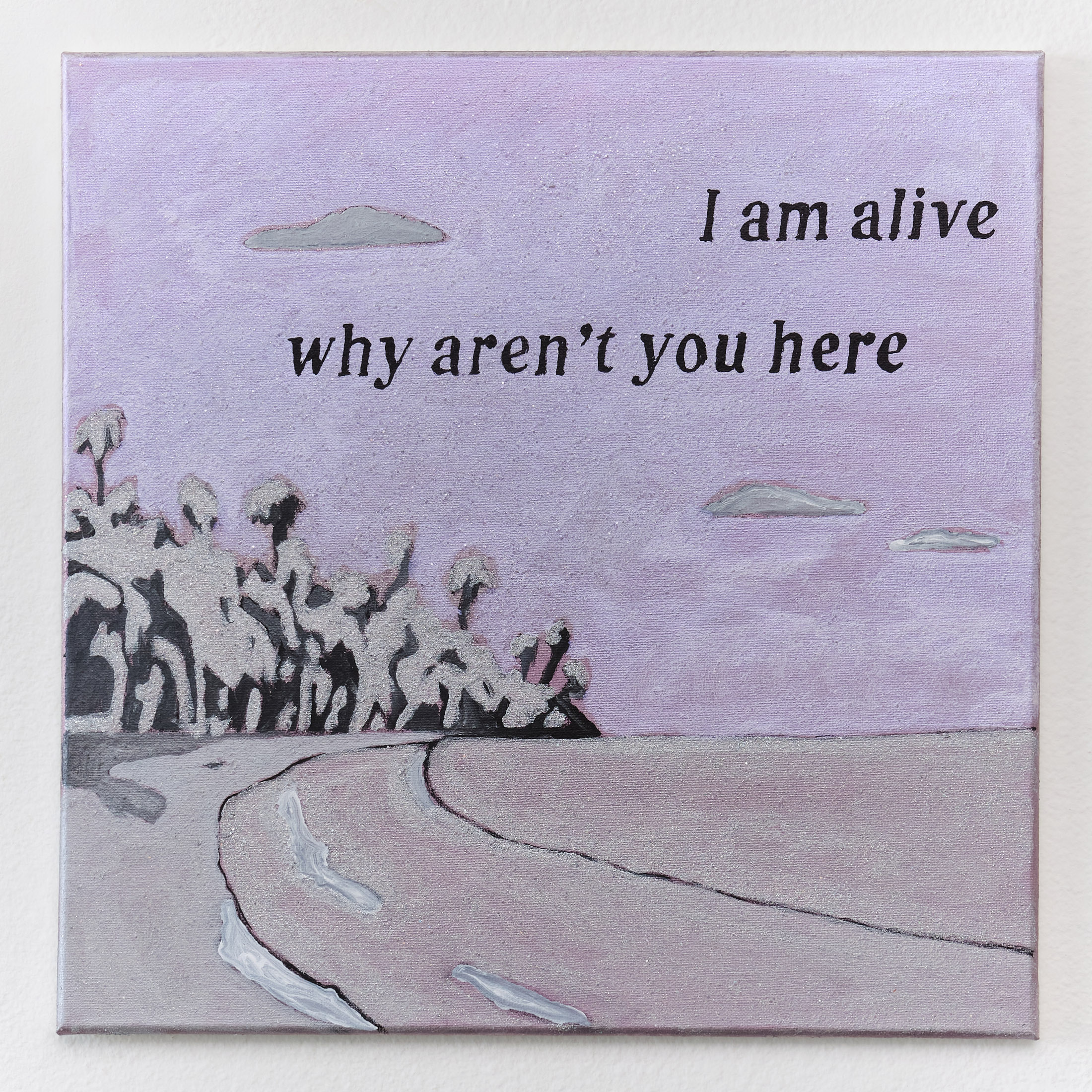

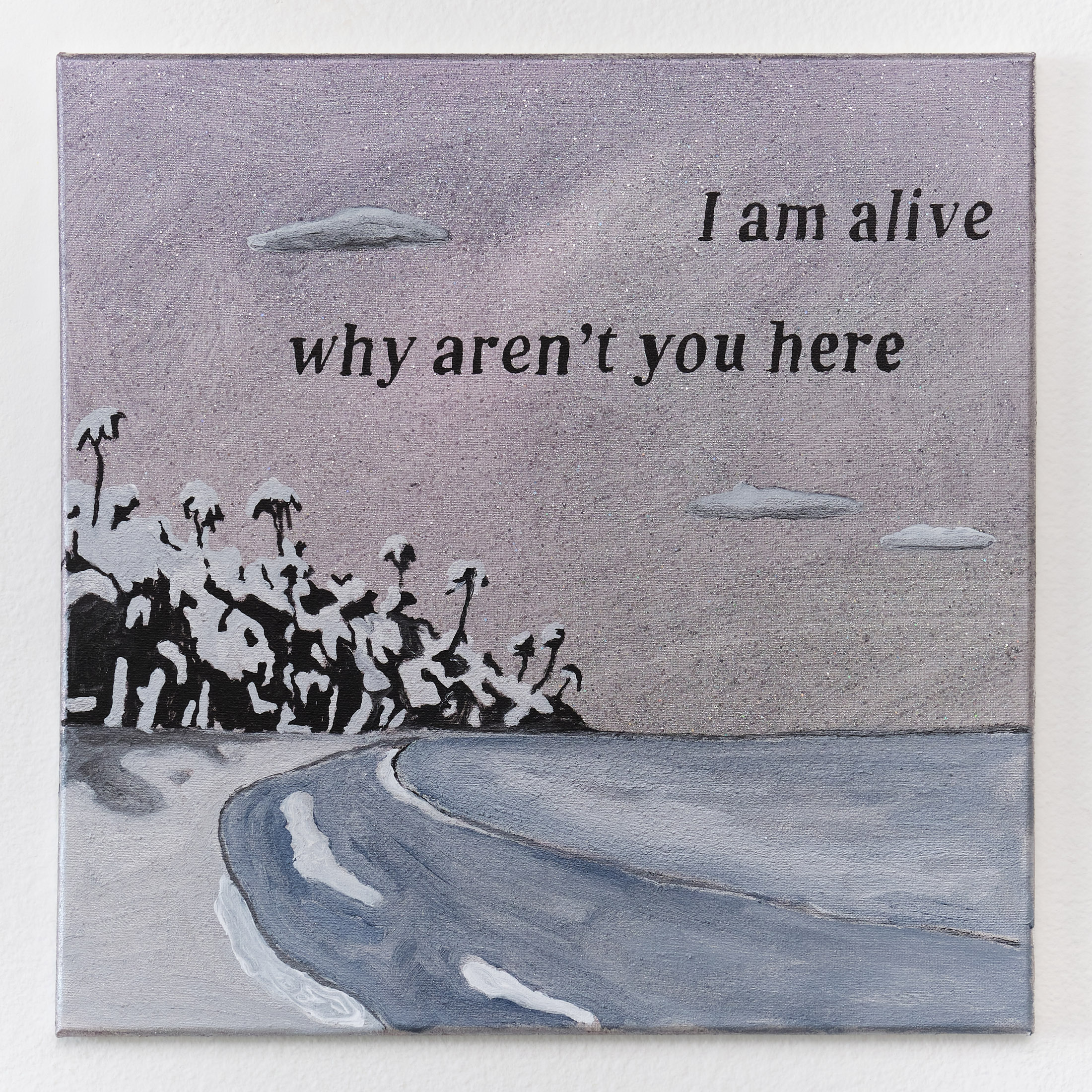

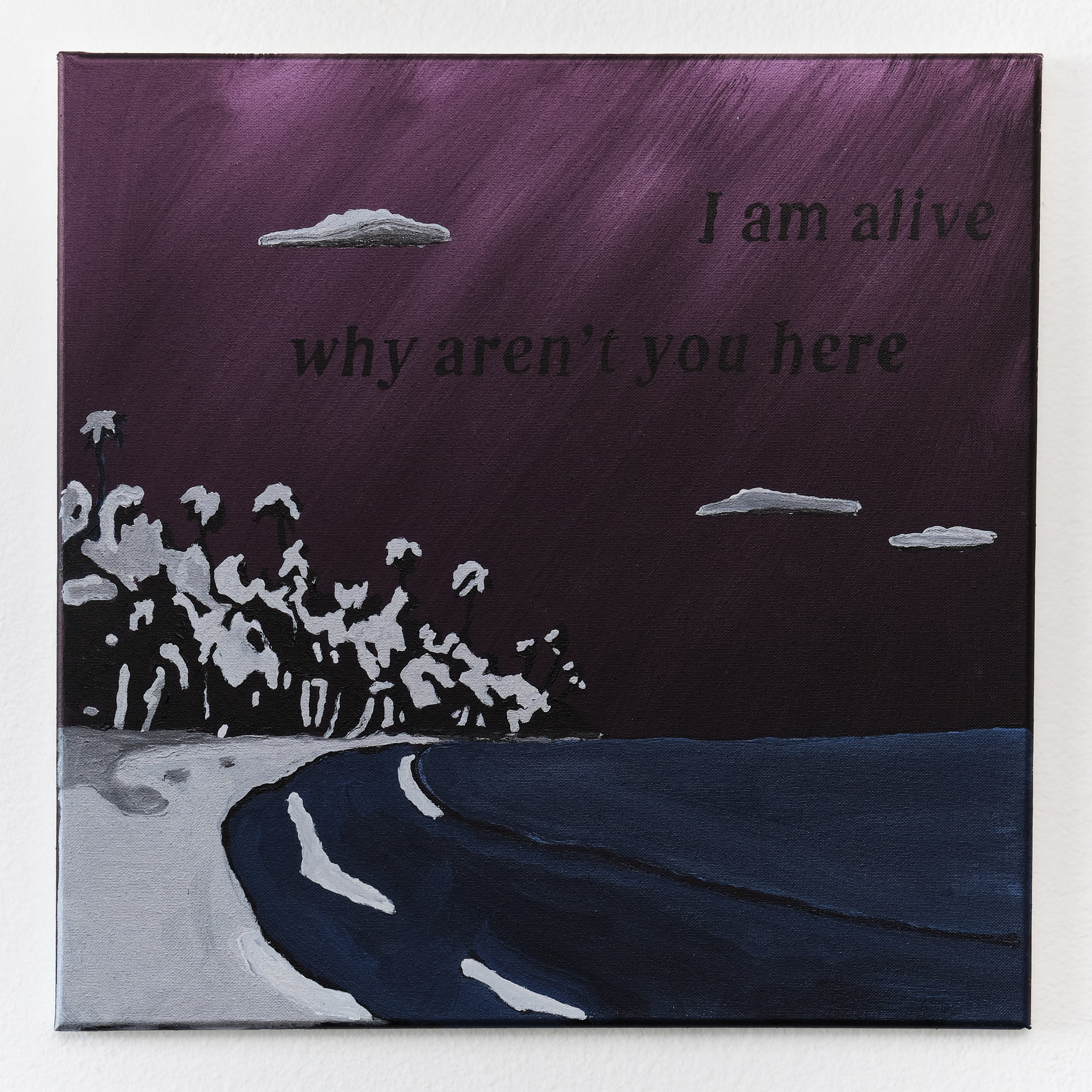

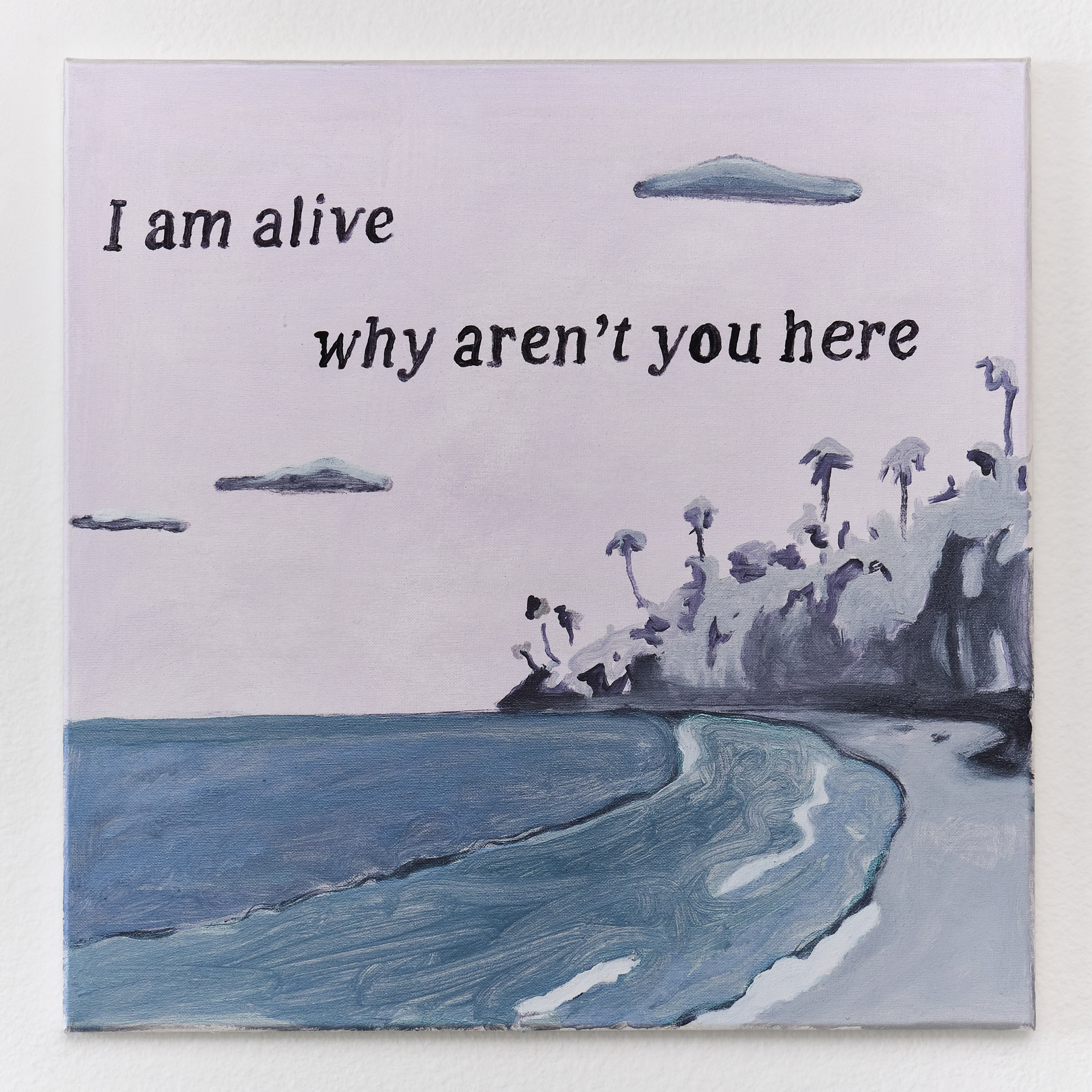

Artist: Gabriel Madan

Exhibition title: Bad Sisters

Venue: MONTI8, Latina, Italy

Date: September 23 – November 18, 2023

Photography: all images copyright and courtesy of the artist and MONTI8

Tell-Tale Hearts

A heart: thick, heavy, substantial lump, all muscle, veiny, throbbing, turgid. Teller of tall tales. Did I say heavy? Yes, a great dull weight lumped in the throat, sunk to the belly. Half-a-pounder with squeeze.

A child I carried inside my body for a time was a week or more late coming out (by the clock of scientific averages at least) and they wanted to start interfering with the situation if all was not well. So I let them put me in a room for two hours, strapped to a device that showed the stowaway heartbeat on a computer screen. I got the wrong end of the stick and I thought they wanted it—my baby’s beating heart—to settle into regularity, so there I sat, doing all this calm breathing and other telepathic and somatic tricks of will whenever the rhythm changed, to try and tame that flexing organ deep inside my belly, to soothe its electrical signal into performing a steady, orderly pulse for the monitor. We were all in fine shape, they said—the heart, the baby, me—we could go home and take our own time. It turns out though, what they were looking for in the transcript wasn’t the metronomic march I was willing upon it, but a life-filled rhythm, syncopated and buoyant in the flow of all the contingencies of that watery grow-bag: responsive.

(Of course, you can’t control somebody else’s heart either way.)

I’m in a dark, choppy sea, not too far from the rocks that edge the cove, but I’m swimming away from the beach, further than I usually go. When you cry in the sea you dissolve into its abundance. I’ve heard that when people submit to drowning and finally inhale, their lungs full of water, it feels ecstatic. Between the up-downs of the waves, if I look back I can see the beach. It appears and disappears with each swell. Everything is gray because it’s dusk and also weathery. I can see both my parents there, far away—small but easy to spot with their luminous white hair. My dad has stood up and is facing directly towards me. His posture seems alert, anxious. I know that I’m rising and falling behind the waves, in and out of sight for them, as they are for me. I feel that the possibility of my disappearing forever is present for them in that moment, as theirs is for me.

The Teatro Regio opera house in Parma is famous for its “impassioned and discerning” audience, who in turn—as a rolling collective—are famous for ardently booing the show if displeased.1 To perform in that space is to invite the possibility of failure, at scale. This is of course what it is to be any kind of artist, or really to embrace any way of being in which you expose yourself to the possibility—the inevitability—of failure. To be a parent, a sibling, a lover, a friend. Your “heart” is at once inside and outside your body. Failure is inherent to the livingness of being present to the world and to each other.

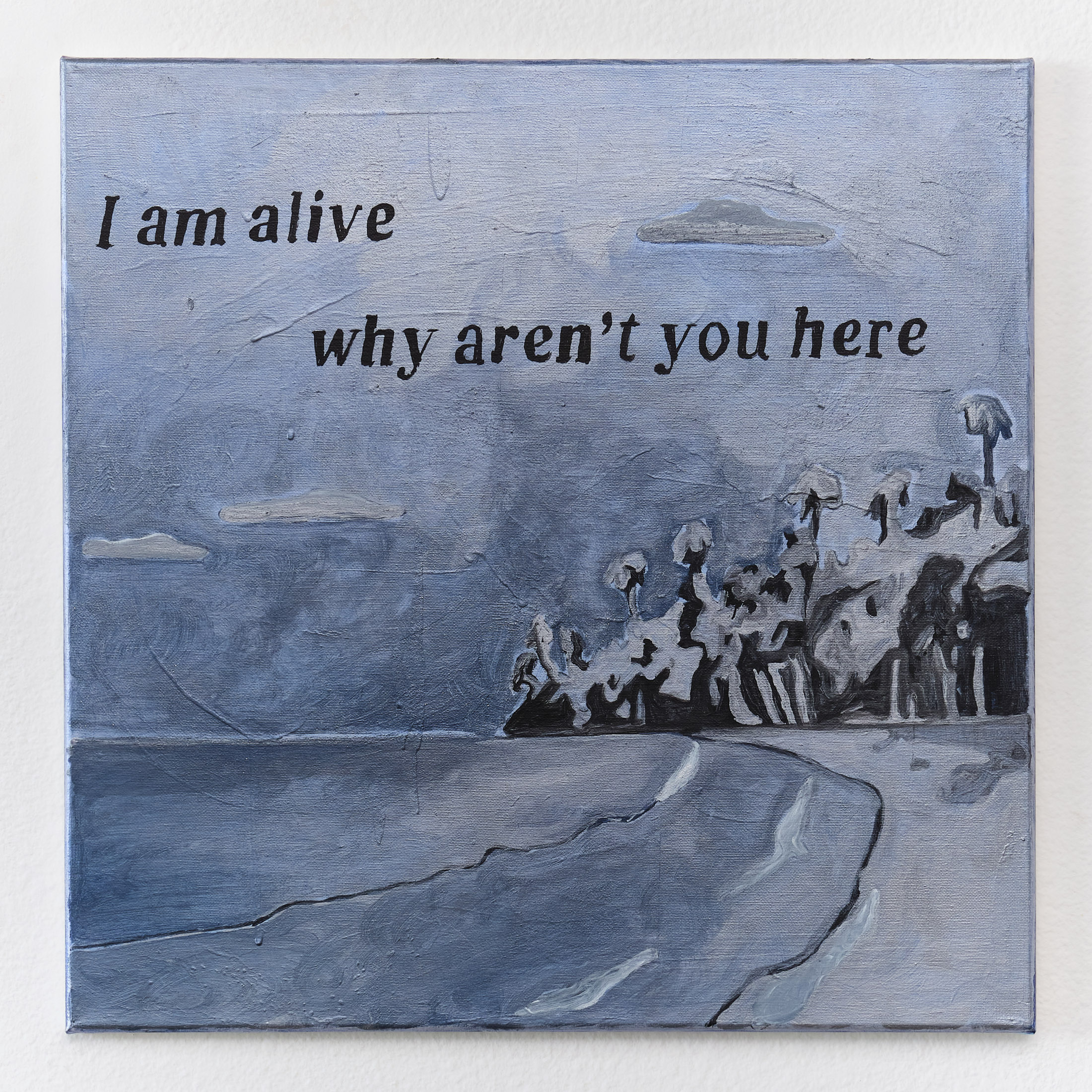

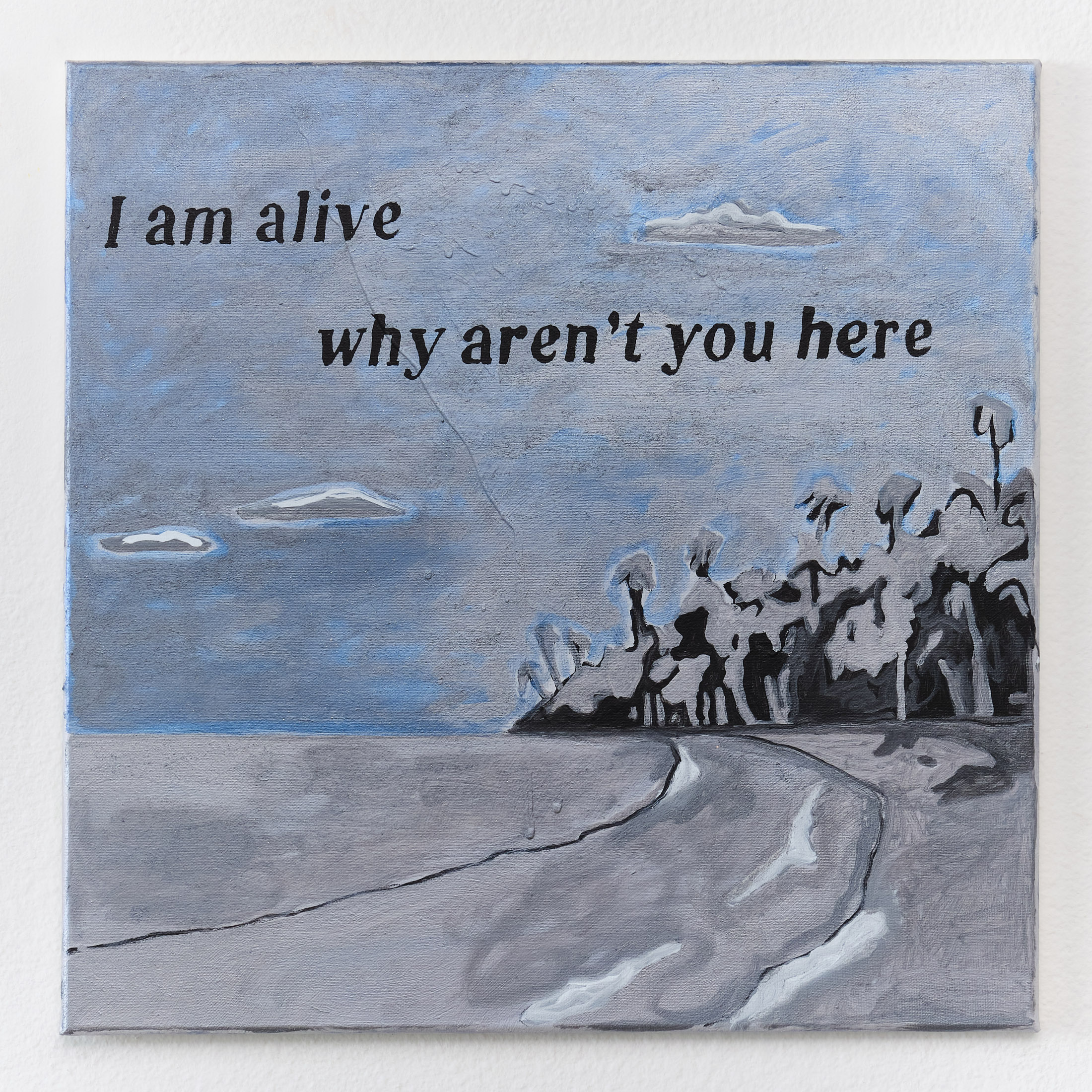

In one way or another Gabriel Madan’s work has these past years been a seance of sorts: in particular for his older sister Rebecca who died in 2015, and in general for a contemporary figure of loss. Rebecca died unexpectedly on a Florida beach. Her body failed her, and those who love her still. “I’m alive why aren’t you here” is repeated across a series of almost identical, gray paintings of a palm-tree-lined beach. They crudely appropriate the lyrical grayscale landscapes of Silke Otto-Knapp and borrow Sturtevant’s irreverence to authenticity. They’re absurd: not-funny punchlines to the not-funny joke of death. They might show up in the Hallmark aisle at Vons, in a world where everything is as it is now, just a little different.2

The dullness of the paintings’ repeated composition is inert, but the shifts are what break it. Even though the pictures are static, it is as if the weather—the darkening skies—pushes through stopped time, appealing to it to start up again. The paintings struggle against their fungibility, their stocky discreteness. Repetition becomes slippery, even as the question they ask is insistent. As a chorus, the paintings reach out of their orderly squares across the dizzying theater of “possible (and inevitable) failure.”

An ocean of anatomically heart-shaped stress balls—One Million Sunsets—scattered on the floor gesture beyond themselves. The inferred incitement to squeeze each of them amounts to a latent durational performance that would take us outside ourselves, like rosaries at a funeral, chanting mantras, swimming out to sea.

We often fall into a thinking trap that it’s desirable to fix things in space and time, that sanity and wellness can be controlled and orderly. But our hearts are carried by living currents, away from sovereign consciousness, away from Cartesian separation, social separation. We are indiscrete beings-in-love, a mutually chaotic collective consciousness that chances failure with every rise and fall.

But lest we get carried away waxing philosophical on the emo tide, this work also lets us know that grief—and art—can also be flat and stupid. Madan’s moves are deceptively workaday: sardonic, ugly, “dumb” (a word he uses often in reference to his own work, and to paintings in general.) They are silly. It’s silly to hang silly paintings on photo backdrops. It’s silly to inhabit bereavement with factory-made foam hearts. (They’re an irreverent nod to Lutz Bacher’s 2012 installation Stress Balls, itself an irreverent nod to quantum physics.) It’s silly to make clumsy fanart-ish copies of historical artworks. It’s silly to give work that comes from bereavement the title of a TV show.3 But while death, to quote Jackie Wang, is “boring as hell”, life should be silly, shouldn’t it?4

-Written by Olivia Mole.

1 https://www.nytimes.com/1992/03/29/arts/classical-music-where-the-audience-is-the-star.html

2 The text of Madan’s painting Who can speak of the future? Nobody knows anything about the future, even the planets do not know is from a Hasidic story typically attributed to Walter Benjamin, who heard it from Gershom Scholem, though it came to Madan by way of Ben Lerner’s novel 10:04, where it is used as an epigraph, quoted from Giorgio Agamben’s The Coming Community. The title of the painting itself is taken from the Louise Glück poem A Children’s Story. Which is all to say that to pull at any thread of Madan’s work is to unravel a tapestry of quotation, appropriation, reference, and reproduction.

3 https://m.imdb.com/title/tt15469618/

4 https://loneberry.tumblr.com/post/1532561291/is-death-queer