Artist: Sean Crossley

Exhibition title: Recreational Painting

Venue: Harlan Levey Projects, Brussels, Belgium

Date: June 6 – July 7, 2019

Photography: all images copyright and courtesy of the artist and Harlan Levey Projects, Brussels

Artists talking (around) painting.

When TR Ericsson visited Brussels last year for his exhibition “Industrial Poems – Poèmes Industriels,” he spent several hours in Sean Crossley’s Molenbeek studio. A few weeks prior to Sean’s first exhibition in the gallery, the two held a second studio visit from a far. Instead of writing about Sean, his practice or paintings, it felt more appropriate to let Ericsson’s email act as an introduction to “Recreational Painting.”

We agreed not to Skype and had a two-hour phone call instead; a sort of virtual studio visit. I had the pictures of his new paintings opened on my computer and I spent a lot time with his actual work in Dallas last month. Plus, I had his voice, so what more did I need? I said I’d ask dumb questions to get started, because it’s a good way into things. Why were his paintings so often “muted,” colorful, but muted, and not in the way of say a Laura Owens’. Sean said he’s looked at a lot of French Realism, which prompted me to send him a link to a book I’ve had since my teens of French Realism from a show at The Cleveland Museum of Art. There’s a weary looking young man on the cover pealing a potato in his impoverished looking home/studio, his eyes fixated on the simple task. “All those artists hung themselves,” I said, though they didn’t all hang themselves. Sean responded something about class structure and made a correlation, but my notes here are unclear.

I took a lot of notes while we talked. It’s a mess of barely legible scrawls on 4 x 5 notecards all over my desk, but I did number them, so they’re sort of in a linear order though our conversation wasn’t. It had a beginning and an end, but there were loops. Painting is a lot like that, linear but looping. My notes missed a lot from our conversation, but when I woke up this morning it all felt fresh in my head so I jumped to the computer to get it down (the sun is finally out probably helped). I thought I could send this all to you in an email, a flowing record of our conversation pieced together through scraps of note taking and then the parts that stood out in memory, a text like a painting, like Sean’s painting- full of puzzling and compelling pieces that fit together somehow, but don’t create a perfectly coherent image, the openness of that, thinking in pictures, thoughts bouncing off other thoughts. There’s something so true in incompleteness. Everyone wants the nailed down version of everything, they need it, but nothing is really nailed down with anything, not with Sean, or with his paintings or with painting and its flow through time and cultures. Everything’s fragmented and open and revolving. I think this is the best way to approach Sean’s current work.

I asked about the paintings you recently presented in Dallas; the doubling, twin images, fraudulence, copies, and so on. Doubling something is a good way to avoid narrative. You get so busy looking between the two images you don’t think anything else and what comes next is something paradoxical.

Sean and I were trained at figurative leaning art schools; figurative realism, painting from life. We both wrestled with it, abandoned it and can’t seem to get rid of it. We can both draw, which isn’t enough. Sean turned to mass media. He talked about working with images he didn’t like. Abstraction doesn’t hold an interest. There was another desire, I particularly liked the phrase he used – “to touch the world outside of painting.”

I used the word “movement” knowing that it’s the wrong word. Sean said “time”, that’s a better word. He said he’s trying to suppress the vitality of the painting. I like that. Why?

Well for one perhaps, The Pictures Generation, getting out of all that.

Sean said about the paintings in his upcoming show, “the background and foreground are the same.” I didn’t ask anything further about that. I liked letting that seemingly ambiguous but perhaps starkly intentional statement just hang there in my mind awhile. As for what the show is in a general sense, and knowing the general sense of it is the least of it, Sean described it as a “conventional” painting show. Genre, portrait and still life. Different sized works from large to small. All straightforward in that sense, but drilling down from there, getting far more complex and multifaceted in aim and intent.

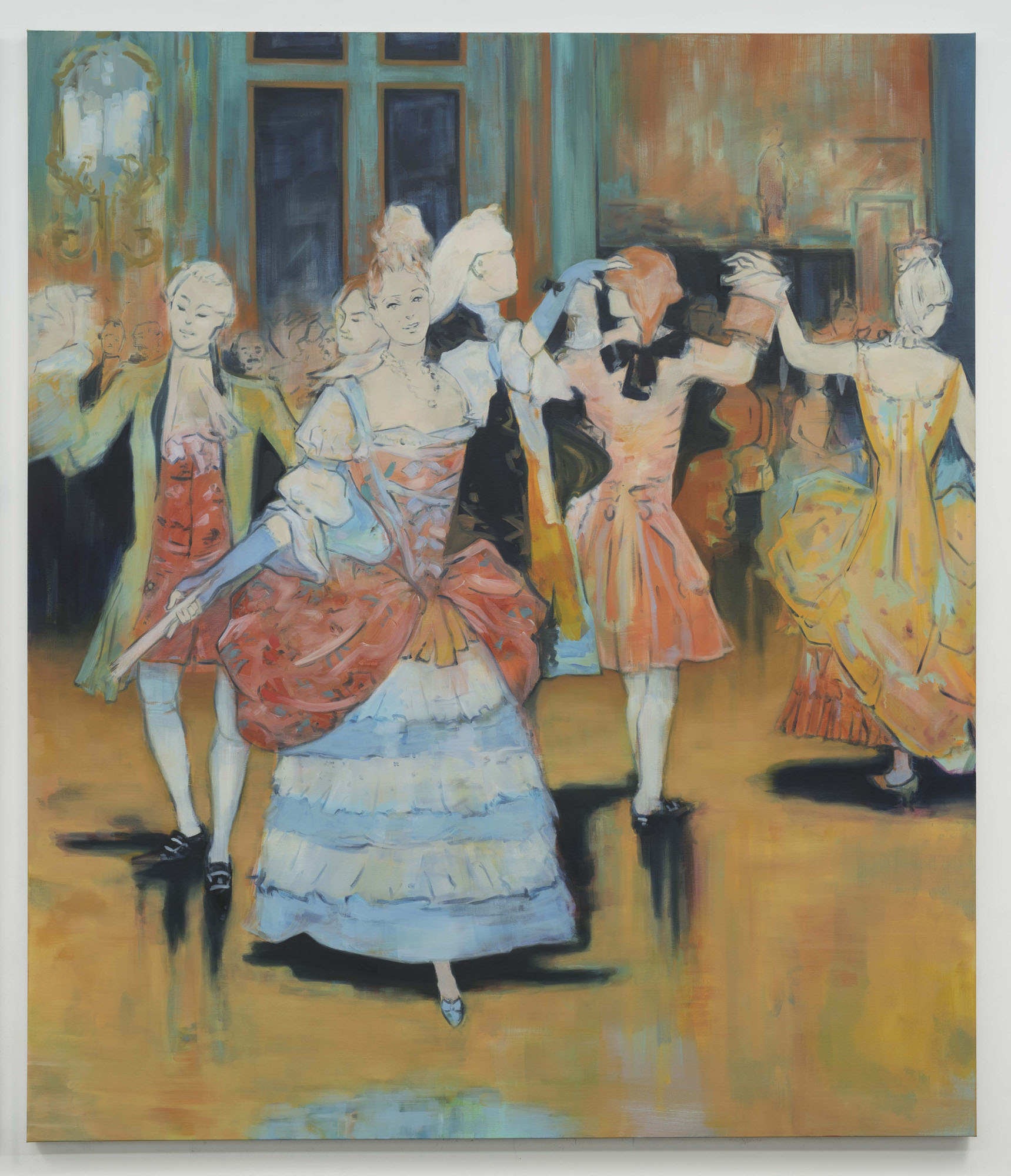

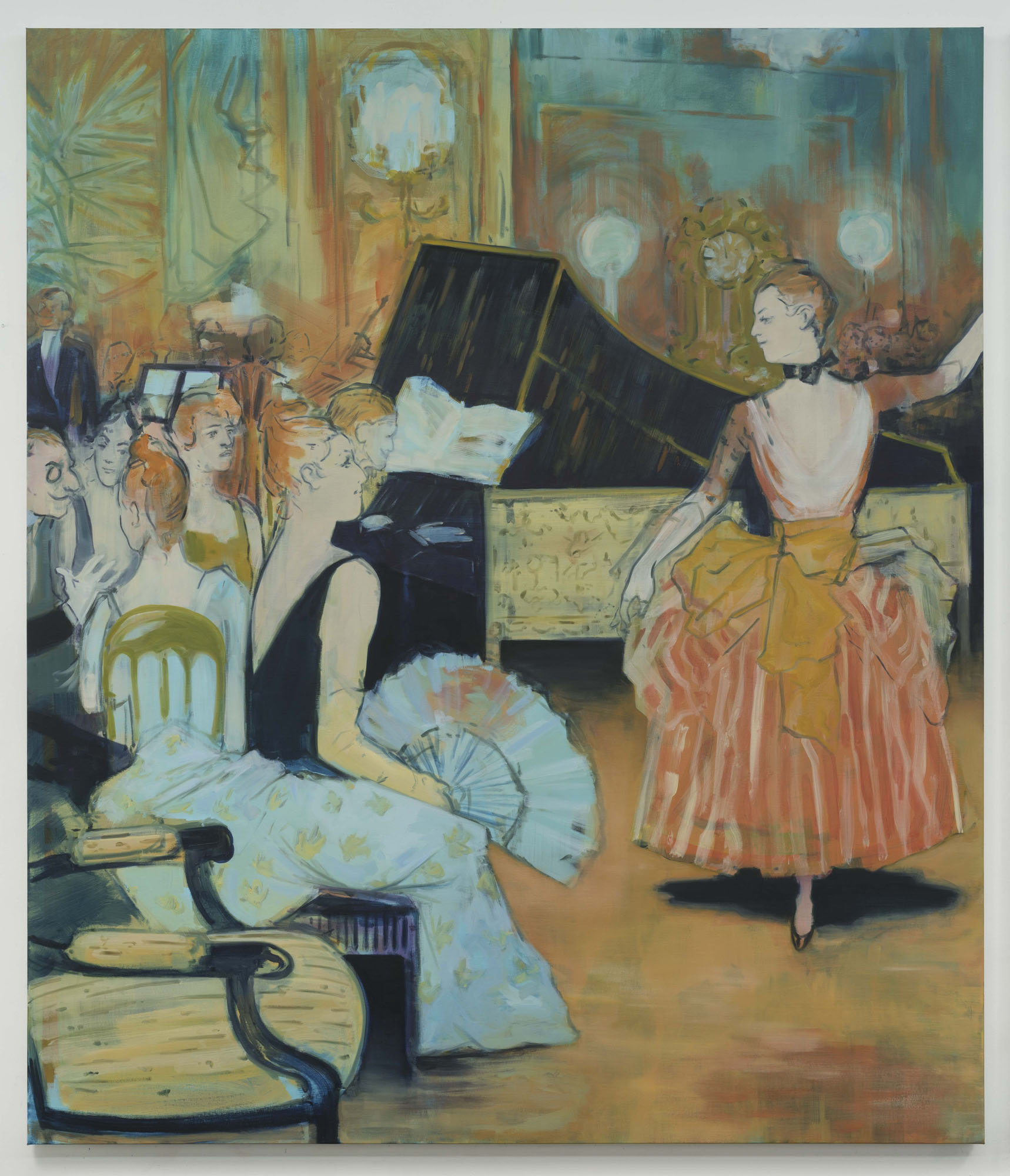

This new set of paintings Sean said are looking at you, they’re looking at each other, in conversation with one another. I could imagine a dance like the menuet, which reminded me of his Holbein work you presented last year in Dallas, the dance macabre embedded in one of those and copying and time and history and now. The space between the work is critical to the work itself. Sean emphasized this point at the end of our talk too.

He’d sent me some texts before our talk outlining the sources for each of the works, but leaving it at that, he rightly said there are things he should not say about his paintings. It’s very important to know that, particularly when things aren’t what they seem, repetitions, why copy the work of such a minor painter (Le Menuet by August Francois Gorguet 1886)? Sean now owns the original lithograph and felt it was important to have that. I know what he means.

Resemblances.

Delirium.

Painting.

Time. Agency.

Lack, pure lack. A stone in the belly that can’t be digested.

We spoke about novelty, K-Punk, Mark Fisher’s take on capitalist realism and the series of Chris Marker inspired faces, “not two, not three, that’s a triptych, so four then.” Sean shared with me a translation of the original Marker quote he relates to this work:

“It is this image that taught a seven-year-old child how a face filling the screen was suddenly the most precious thing in the world, something that came back constantly, that mingled with all the moments of life, of which to say the name and describing the traits became the most necessary and delightful occupation – in a word, what love was.”

We talked about a painting recreating itself, about outdated spaces, outdated paintings, his or anybody else’s. This refers to the menuet work, the Powder club and painting over his own works- how an absence of brushstrokes gives him a way back in to the painting allows him to cover over the last images or layers of paint.

What about the stock? The cook, television screens, recipes, conventional painting, that’s what a family recipe is all about, it’s repeated handed down, more copying, doubling, repeating all the way to a Michelin star.

Then more tangents. Recreational leisure scenes like yoga, sport (touching the world), Manet, Daumier, especially Daumier. Painting is social, painting is sociological, Sean’s paintings are anyway.

I told him how the paintings made me think of Giacometti and Cézanne, because we already had talked about Kitaj (for all the thought he puts into each picture), Paintings that are made with a profound uncertainty at every stroke and get you thinking the longer you’re looking at them. It’s true to the chaos of painting, intuitive is the word I use to describe it (à la Giacometti and Cézanne), you don’t know where you’ll end up. It’s maddening to be open to that – he also talked about Nietzsche. Said he read somewhere that you can’t understand Nietzsche’s late work unless you know his body and mind were falling apart.

“Good paintings are hard to talk about.”

Sean mentioned some contemporary German painters, his interest in them. I didn’t know the names he mentioned so we talked about the difference between the US and European painters now. Paintings I’m critical when it looks like they were first created in photoshop then actualized. He quoted a philosopher – saying that the real meaning of the word digital is the reduction of the hand to one finger, the hand can do more, what a hand can do is more multiple.

Thinking of the over painting in his work, I think of pentimento, nerdy art speak for the way you can see the underpainting coming through in an old master painting, Sarto is well known for this. It’s interesting because you see the changes, the literal thinking within the painting, like ghosts, the decisions begin to show themselves, can even be meant to show themselves. Time and thinking rise up through the paint layers, whatever it is, it’s beautiful, whether literally or not. This is a Sean thing; thought, time, change, decision, revision, something over top something else, obliteration, repetition, resurrection. It’s also a painting thing. In general, it’s what is real about it, what the hand and mind and eye are doing from start to finish, the evidence of that. To witness yourself thinking and doing and being. For others to witness you thinking and doing and being.

“There is a social and political groundwork,” Sean said, as we followed painting through abstraction asking how to communicate or define the non-representational.

We circled back to Manet and I mentioned Larry Rivers. Sean said you can’t look at two eyes at the same time, I didn’t mention how I first came to notice that and how nuts it made me feel or how I solved the problem for myself and I still do this by gazing at friends during conversation into one eye or the other. There’s a good story about Pollack talking to Larry Rivers, Pollack kept repeating to him and I imagine looming over him from behind like a hulking bully, “I know what you’re doing, I know what you’re doing” something like that, meaning the bounce between the visible figurative elements and the wiped-out absences in the images.

We ended our conversation talking about another painter, about something crazy the painter did that you would never know they did, it’s even a kept secret, but that when you hear it you understand it has a lot to do with why the paintings feel the way they do, I think Sean said they were insane. In a generous way he said he was jealous of these works. He said that a couple times. It’s unusual to hear an artist talk like that, I mentioned Duchamp, Sean also loves Duchamp, I didn’t say it but I know we both know it, Duchamp is like the buddha and the buddhist saying if you see buddha coming down the road kill him, Duchamp’s rebellion against the French phrase “dumb like a painter”, how he challenged that, fighting against

that but the dumbness of the thing (painting) the unpredictable animal like way you have to approach it’s convoluted possibilities, that’s still a part of it, a certain dumbness you have to accept, it’s going to drive you to some unexpected places no matter how much you think about it. I like that Sean gets that, so much intelligence at play with itself and the world and the paintings, but also this brute thing that painting is and being open to that and honest about that. Somewhere he said how symbolism and whatever other clever crap you can think of is just boring to him these days. I agree, I’m always lapping in the large warm bath of the quotidian and banal as the most un-boring thing I can think to do.

Back to the “recreational.” Other than the idle things we do with our spare time and how interesting those things can be, I may not know what Sean means by “recreational,” though he seems to relish that word regarding this work, but I like what I think it means and what I think I can’t say about that, the words a lot of them that point to this work or swim around this work float like marks in a painting they mean everything and nothing. Writing or talking about music is like dancing around architecture

(this is a quote that has been attributed to multiple people from Laurie Anderson to Elvis Costello and Frank Zappa and George Carlin and whoever else), is a good quote to end on. Talking or writing about painting is like dancing around architecture, Sean’s work is like this, pinning it down, pigeon-holing it, would be bullshit. Sean is young in years which doesn’t mean anything, I’m sure he’s smarter and far more talented and informed than countless others his age, but the age thing still matters in one way and he mentioned it himself, it’s just about putting in the time as yourself and how much that matters and how long that takes, but the early years, and he’s deep into them, count for a lot. In Sean’s case they count for a lot, the armature is there, the framework is very sturdy, and I don’t know how he’d take this comment but there’s a style there, there’s always a style to a good group of paintings, more or less recognizable but the underpinnings of a style are present in Sean’s work in the most attractive it-just-is wordless way, in addition to all the stones I imagine there are stuck in the belly of his mind there’s a fire there too. A fire that will continue to burn and be worth watching. Take the time and you’ll feel the thinking and you’ll make the connections and you’ll be eager to return to this work now and future works later.

I like the way our talk ended, Sean had to piss and my buzzer went off from downstairs, UPS, with a delivery of who knows what the fuck I’m doing boxes for a new project, not a painting at all but still driven by pure lack and delirium. Like all this is…

Sean Crossley, Recreational Painting, 2019, exhibition view, Harlan Levey Projects, Brussels

Sean Crossley, Recreational Painting, 2019, exhibition view, Harlan Levey Projects, Brussels

Sean Crossley, Recreational Painting, 2019, exhibition view, Harlan Levey Projects, Brussels

Sean Crossley, Recreational Painting, 2019, exhibition view, Harlan Levey Projects, Brussels

Sean Crossley, Recreational Painting, 2019, exhibition view, Harlan Levey Projects, Brussels

Sean Crossley, Recreational Painting, 2019, exhibition view, Harlan Levey Projects, Brussels

Sean Crossley, Recreational Painting, 2019, exhibition view, Harlan Levey Projects, Brussels

Sean Crossley, Recreational Painting, 2019, exhibition view, Harlan Levey Projects, Brussels

Sean Crossley, Recreational Painting, 2019, exhibition view, Harlan Levey Projects, Brussels

Sean Crossley, Body Clock, 2019, Oil on linen, 160 x 203 cm

Sean Crossley, Bouquette, 2019, Oil on linen, 42 x 35 cm

Sean Crossley, Le Menuet I & II (after August Francois gorguet 1886), 2019, Oil on linen, 210 x 360 cm each

Sean Crossley, Le Menuet I (after August Francois gorguet 1886), 2019, Oil on linen, 210 x 360 cm

Sean Crossley, Le Menuet II (after August Francois gorguet 1886), 2019, Oil on linen, 210 x 360 cm

Sean Crossley, Ressemblance II, 2019, Oil on linen, 42 x 35 cm

Sean Crossley, Ressemblance III, 2019, Oil on linen, 42 x 35 cm

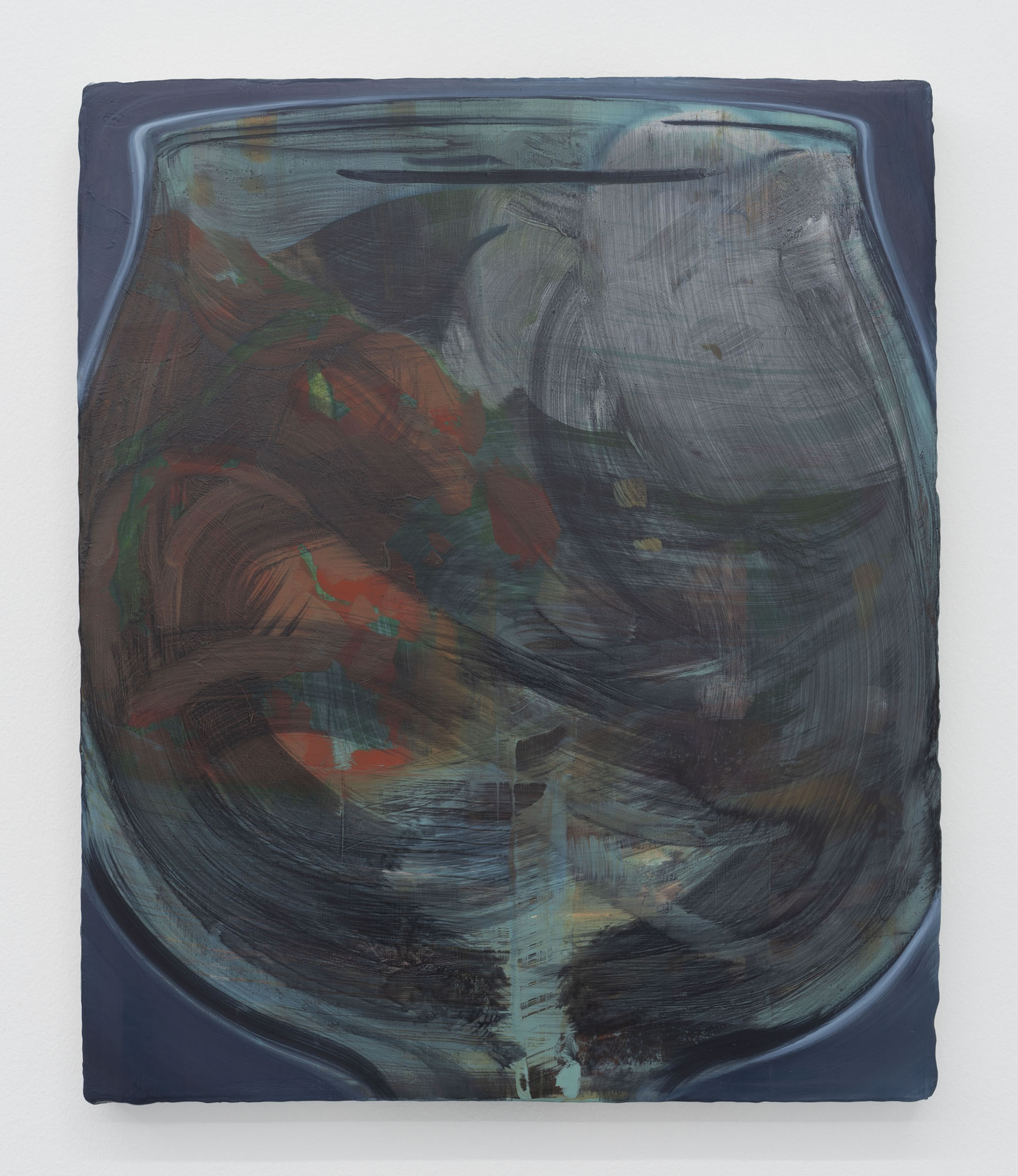

Sean Crossley, Savons, 2019, Oil on linen, 40 x 47 cm

Sean Crossley, Stock, 2019, Oil on linen, 80 x 120cm