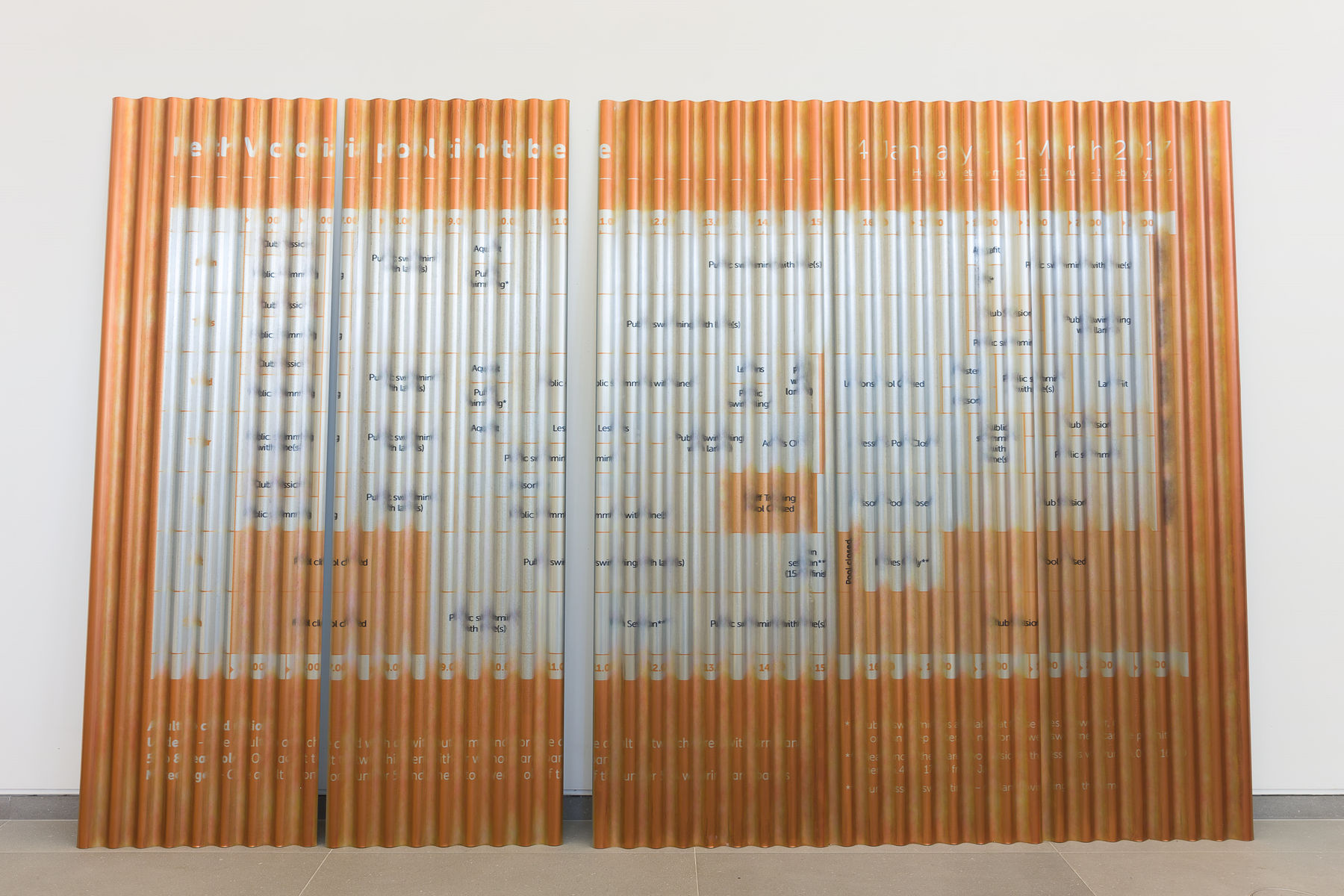

Artist: Keith Farquhar

Exhibition title: HEADSPACE app

Venue: Cabinet, London, UK

Date: September 1 – 29, 2018

Photography: all images copyright and courtesy of the artist and Cabinet, London

Note: Exhibition text can be found here

Keith Farquhar’s exhibition brings together a collection of material fragments drawn from contemporary life. Each of these fragments provide clues to activities undertaken, or phenomena observed first-hand. They refer to, amongst other things, the artist’s daily commute on public transport, his use of meditation apps or the respite from stress regularly taken at a municipal sauna.

Beyond the glimpse of Farquhar’s biography these elements provide, his subject matter reflects broader shifts in cultural policy, specifically imperatives that have acted to reposition the artist in relation to the concept of a ‘creative economy’. An artist’s financial precarity, once considered an esoteric form of delinquency, now functions as the blueprint for a host of other forms of self-organised labour. Similarly, artist’s studio complexes, previously provisional spaces located in less desirable locales, have been rebranded as purpose built, public facing institutions: hubs of exchange complete with their own modish canteens, merchandising departments and outreach programmes.

Here these indicators of cultural ambiance, progressive though they might ostensibly seem, appear alongside the visible signs of a parliamentary abdication of responsibility for our well-being as citizens. Edinburgh Leisure, the namesake of Farquhar’s audio/visual performance project with Tim Fraser, and an entity who have provided the source material for a number of his recent artworks, is a health and fitness trust operating at ‘arms-length’ from local government. Much like the thin veneer of neutrality offered by the Metro (a tabloid owned by DMG Media, publishers of The Daily Mail) this organisation is symptomatic of the mission creep of privatization and vested interest into every aspect of civic life in the UK.

It is to this burgeoning reality – a reality in which an increasingly utilitarian vision of creative agency and the pervasive expansion of free market thinking dominate – that Farquhar’s work supplies an iconography. At once dismissive and poignant, his gestures and arrangements embody both social commentary and a sense of tragedy. They dramatise an existential threat to notions of artistic sovereignty, as well as the social infrastructure upon which such freedoms can be claimed.

-Neil Clements