Artists: Atelier E.B, Tauba Auerbach, Katja Mater, Lucy McKenzie, Beca Lipscombe, Eileen Quinlan, Božena Rothmayerová-Horneková & Civilised Woman, Kató Lukáts, Madeleine Vionnet

Exhibition title: ’33 – ’29 – ’36

Curated by: Lucy McKenzie

Produced by: Are | are-events.org in association with the Academy of Arts, Architecture and Design in Prague, the Museum of Applied Arts in Budapest and the Museum of Decorative Arts in Prague.

Venue: UM Gallery, Academy of Arts, Architecture and Design, Prague, Czech Republic

Date: December 20, 2016 – February 25, 2017

Photography: Katja Mater, all images copyright and courtesy of the artists and Are | are-events.org

Note: Exhibition text and floor plan can be found here

In 1929, a project in Brno, Czechoslovakia, tried to produce some answers to a conundrum that Modernism had so far failed to resolve: the so-called ‘woman question’. Entitled Civilised Woman, this was an exhibition and a book in which its organisers, a group of avant-garde designers including Božena Rothmayerová-Horneková, proposed a functionalist way of living based on the primacy of the trouser suit and short hair. It devised practical outfits for the related spheres of work, leisure and pregnancy, and placed women in the labour-saving ‘Frankfurt Kitchen’. But other than advocating chopping off long hair braids and keeping house more efficiently, Civilised Woman had little to offer in the way of real emancipation. In the interwar period, the figure of the New Woman, with her exaggerated visibility, was a symbol of Modernity that was both seductive and troubling to society. The doctrine espoused by this exhibition and book was one that equated femininity with the irrational, and adornment with primitivism, very much like Adolf Loos’ theories outlined in Ornament and Crime. Women, preoccupied and narcissistic, held progress back; their ‘womanliness’ therefore had to be eradicated. In the project itself, that clash between ideology and reality was encapsulated by Rothmayerová-Horneková’s drawings of trouser outfits, which follow the stylistic rules of contemporary fashion illustration to the letter while claiming to reject girlish frivolity. The fundamental inconsistencies in the project’s message are most clearly epitomised, however, in the realistic, ultra-feminine mannequins wearing incongruous jumpers and slacks. Clearly, the civilised women they promoted could not exist outside of propaganda.

If the question is about something that appears radical yet is nothing of the kind, then Civilised Woman finds its counterpoint in the figures of Madeleine Vionnet and Kató Lukáts. Vionnet was an eminent French couturier in the same interwar period. Superficially her work seems to be all about glamorous ‘red carpet’ gowns, but in terms of defining an emancipated female identity within Modernism she is worth a closer look. She espoused her own rationalism; dress patterns were simplified to geometric abstractions derived from her knowledge of both the behaviour of fabric and the human body in motion, paving the way for the sportswear that transformed dress throughout the 20th century. Her designs were often at odds with the period’s insatiable appetite for novelty because she was partial to timeless ideals, such as dynamic symmetry in the natural world and the proportions of Classical antiquity. Her authoritative synthesis of movement and abstraction did not negate femininity; on the contrary, her clothes turned her clients into supple, Futurist goddesses, and it was this, alongside her humane employment practices, that made her an agent of accelerated progress.

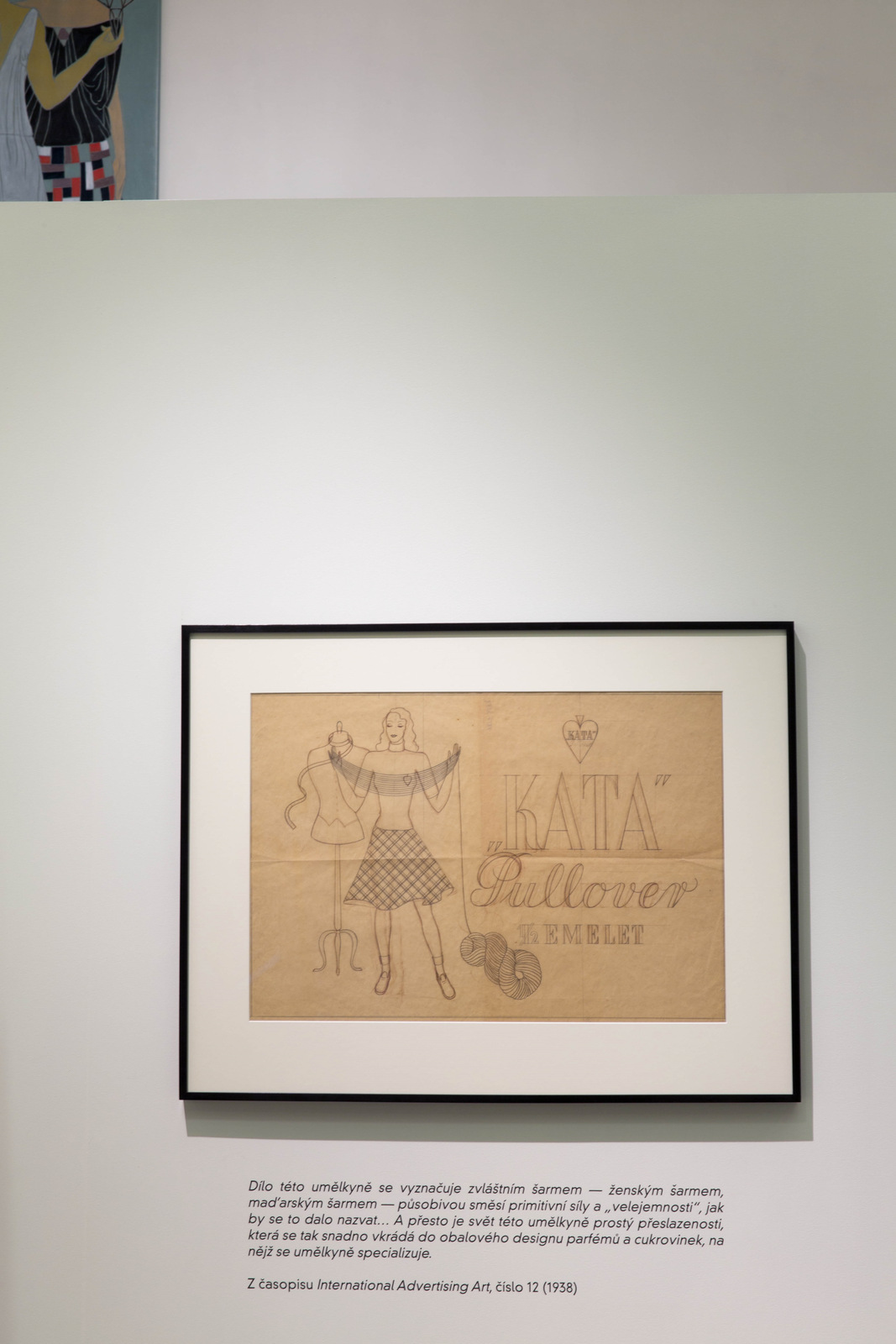

Neoclassicism reinterpreted anachronistic forms and combined them with new materials and Modernist ideas. In a similarly experimental way, the graphic designer and illustrator Kató Lukáts worked with conventional imagery to produce a personal vision within the restrictions of consumer culture that became a great commercial and artistic success. Her compositions, and particularly her use of repeat patterns, depict a seductive kaleidoscope of archaic ideals embodied in such things as religious festivals, childhood games and nostalgia for the Austro-Hungarian Empire. But these sentimental cyphers are so streamlined that they become instrumentalised for her own will and project. She often used hybrid archetypes – in one illustration an elegant 1920s ‘flapper’ stands in the foreground, while framing her is the silhouette of a historical figure, complete with crinoline skirt and ringlets. Just as in Pauline Réage’s classic erotic text The Story of ‘O’, in which ‘O’’s sexual pleasure is formalised through eighteenth-century costume, Lukáts understood that the generation and promotion of pleasure is facilitated by fantasy, and layering the past and the present. Almost completely unknown today outside of her native Hungary, Lukáts worked in the Interbellum with commercial packaging, advertising and illustration, and her clients included manufacturers of confectionary, automobiles and underwear, as well as the promoters of fashion and tourism. Collaborating with her husband Gyula Kaesz, she also produced interior decor. After World War II, her work shifted to illustrating children’s books, and as private business evaporated under Communist rule, her previous work exposed her to antibourgeois criticism.

Taken together, the achievements of Rothmayerová-Horneková, Vionnet and Lukáts form a complex set of intersecting aesthetic concerns, with the dualisms of Feminism and the feminine, pattern and repetition, antiquity and the ultra-Modern lying at their heart. They show how radicalism can be hiding in plain sight when measured by the usual narrative standards, and how representations of emancipation and oppression can be misleading. They also provide a compelling illustration of how fashion and the applied arts can act as a kind of double agent, oscillating freely going between opposing forces.

For this exhibition Lucy McKenzie has invited a number of contemporary artists and designers to respond to these issues. These include practitioners working with geometry and abstraction, who were asked to consider how such concerns relate to their sense of female identity, and whether they regard these seemingly ‘timeless’ structures as relevant to contemporary discourse. Similarly, the designers were invited to respond to the complex and conflicting messages of Civilised Woman. After all, we still operate in a culture in which notions of femininity act as a controlling force on women’s behaviour, while at the same time fashion and consumer culture can themselves be a major site of feminist agency.

Atelier E.B is a design company that was set up to facilitate a creative collaboration between the designer Beca Lipscombe and the artist Lucy McKenzie. For ’33 – ’29 – ’36 they have focused on the display techniques that make Civilised Woman such a fascinating project, exploiting the resonance between their own fashion collections and the spirit of Božena Rothmayerová-Horneková by including, for example, capsule wardrobes of practical workwear onto which more complex elements have been layered. Outfits include workcoats, outerwear and adaptations from sportswear, such as polo shirts and jogging bottoms. Their designs are shown on the same kind of anti-Modern mannequins used in Civilised Woman, and by bringing different styles and periods into confrontation they expose how hierarchies of taste are formed and enforced. Beca Lipscombe has produced a series of printed posters responding to elements of Civilised Woman’s ideology, exploring what happens when practicality and adornment meet.

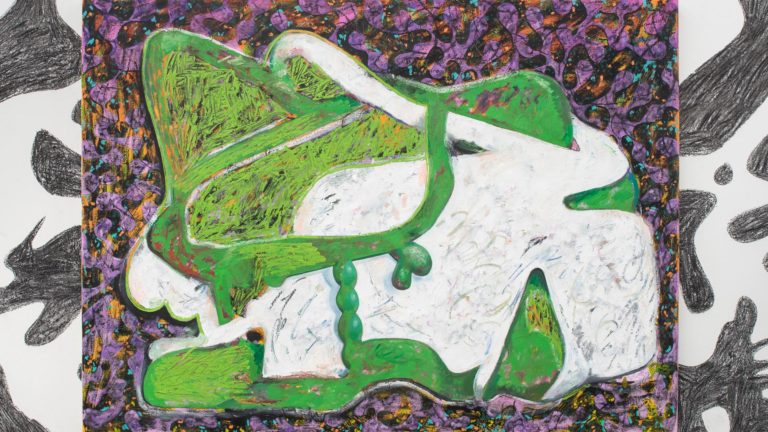

Tauba Auerbach’s Mobius and Ziggurat pop-up sculptures work with the same kinetic potentiality that typifies Vionnet’s use of flat patterns, and are activated by the same combination of movement and tension. The set of digitally printed Meander Helix sculptures are three-dimensional extrapolations from the repeat structure of the Classical Greek ‘meander’ ornament. Each sculpture tests the base pattern with a new dynamic or conceptual twist, subjecting it to gestures like extrusion or rotation. Also on show is A Partial Taxonomy of Periodic Linear Ornament — Both Known and Speculative — Arranged by Symmetry, Dimension and Iteration. In its entirety her work is presented with custommade display elements that extend her study of the structures of decorative pattern, assimilating historic research into her practice.

To produce her repeat pattern photographs Katja Mater superimposes multiple exposures documenting the manipulation of physical space. The space, in this case the gallery, has been transformed with a systematically painted mural, and the resulting photograph is then transformed further with its repetition to produce a pattern composition. In this way she creates abstraction from the material, fully integrates painting and photography, and uses time as a fourth dimension. The unique procedure employed to create her images, and the fact that the construction is ultimately disguised, echo the work of fashion couturiers, in which hours of labour and years of experience produce gowns that appear effortlessly blown together.

Lucy McKenzie explores how reproduction painting and drawing can function as historical research. Like photography today, line drawing was a primary form of documentation and dissemination in the fashion world of the Interbellum, and was ‘read’ by professionals and the public in a way that seems inaccessible to us now. Looking at Vionnet, Lukáts and Rothmayerová-Horneková, the artist inhabits the style of each, replicating the way they used line drawing to transmit both facts and ideas. In the same way that taking a dress apart can unlock its secrets, repainting and drawing historic works can reveal aspects of the artist’s motivation that would otherwise remain hidden. McKenzie has interpreted the murals that decorated Madeleine Vionnet’s Paris salon, painted in 1923 by Georges de Feure. They depict Assyrian, Egyptian, Byzantine and Roman figures wearing Vionnet’s own designs. She has also made fashion illustrations for Atelier E.B in the Civilised Woman style, and Elle Cigaretta, a counterfeit Lukáts package design.

Eileen Quinlan presents a selection of the polaroid prints that she uses as part of the working process for her final still-life photographs. These images are unstable in several ways. Usually shot on out-of-date stock, their chemical composition changes as they age, while as works in progress they expose the mechanics of her methodology as it approaches the refinement of the final image. Quinlan is often inspired by fashion and beauty advertising, and by Modernist photographers such as Lee Miller and Florence Henri, who worked professionally in the field to support their artistic practice. The works here, with their miniature scale and vivacious colours, draw one in to decipher the scenes in the way one wishes to shrink and inhabit the lyrical compositions of Kató Lukáts. The work recognises the complex personal and gendered narratives that lie behind the perfection of commercial advertising images.